ALWAYS THIN AND GRAVE

ACT II.

VII.

⸻

“The New York Morning Journal, under date of September 5th, devotes three-quarters of a column to a minute description of our new Theosophical Headquarters,” said Judge, reviewing the Theosophical activities. It was Tuesday, October 16, and the Aryan Branch was having its regular meeting. “The account is especially interesting because of its fullness,” Judge continued. “It will doubtless draw increased public attention to the fact that Theosophy is not a visitor to, but a resident of, the West. We cannot engage to procure copies of this article but presume that they may be ordered from the editor.”[1]

William Quan Judge.

Judge sometimes smiled, but he rarely laughed. He had a mellow Irish wit, with an “air of melancholy humor” about it. Some heard in his voice “the faintest suspicion of Irish brogue,” while others heard in it the “slightest indication of an American accent.”[2] He was an ordinary man; an Irish emigrant boy “none too well-educated,” but a clever lawyer, and a good, simple man. His charming smile, and gray, luminous, eyes, were his only real claims to attractiveness, but one had to know him very well to learn the reason for his luminous eyes. Judge did not care to talk, he much preferred to listen. It was not uncommon for him to sit quietly in a corner an entire evening, and never open his mouth, giving the impression that he would rather not be noticed. This was also evidenced in the plain clothing he wore.[3]

Madison Square Park.[4]

“The project of starting a Theosophical Sunday School in Boston has been mooted. It ought to be carried forward,” said Judge. “Members should not allow their children to go on imbibing error in sectarian schools, leaving them to the terrible task in later life of combatting the delusions now promulgated every seven days all over the land. We Theosophists need to wake up. Why cannot one member with a home devote his parlor Sunday morning or afternoon, and other members bring their children and teach them Reincarnation and Karma, making the hour agreeable with music and with amusing and instructive conversation removed from the ridiculous incubus of Old Testament views and dogmatic Christianity?”[5]

Sattay, who was speaking that evening on the topic of the Hindu caste system, loosened the neckcloth that he wore to protect his throat.[6] “If I might judge from actions, I should say that Theosophists are the real Christians.”[7]

Julia Campbell Ver Planck.

A series of Theosophical children’s stories, and even a “Theosophical Catechism,” was proposed by Judge’s close friend, Julia Campbell Ver Planck. She lived in Wayne, Pennsylvania, but as she assisted him with editing The Path, she was not an infrequent visitor to the New York Branch.[8] A playwright of some renown, Julia won praise in 1884 for her dramatic retelling of the Salem Witch trials in The Puritan Maid.[9] This was followed by a drama called Sealed Instructions which had a very successful run at Madison Square Theatre in the spring of 1885.[10] Like her fellow Theosophist, E.D. Walker, Julia was also a contributor to Harper’s Magazine. Her father, James Hepburn Campbell, was the former American Minister to Sweden, and her mother, the poet, Juliet Hamersley Lewis.[11] Julia joined the Society in May 1886, after attending a lecture by Arthur Gebhard with other women of the New England literary circle (Anna Lynch Botta, Celia Thaxter,) in the parlors of Sara Bull, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Despite her successful career, Julia’s life was marked with tragedy.[12] A decade earlier her entire family died; first her two boys, James, and Gordon in 1875, and then her husband, Phillip, in 1876.[13] Her boys were still infants when they passed away, and Judge understood well the sadness which lingered from such a loss. In a letter dated April 29, 1886 (around the time that Julia joined) Judge writes: “I do not deem it possible for me to enter into a mother’s feelings, but I have been a father from whom a daughter was snatched away in two days while she was in the flower of health.”[14]

“It is with a trace of sorrow that we record the fact that The Path has not been supported by subscribing theosophists, but mainly by those who are not members of the Society.” Said Julia.[15] “This should not be the case. The magazine is published in the interest of Theosophy, and never generates money, but is rather a loss to Mr. Judge.”

It was owing to this fact that Julia initiated a scheme (with the approbation of the Theosophical Publication Society of London and The Path,) whereby she sent out circulars (to Theosophists and non-Theosophists alike,) soliciting aid in publishing theosophical literature.[16] Each person was asked to send ten cents and make two copies of the circular for friends. These friends, in their turn, would give ten cents and send the paper to other friends.[17] The plan was a success, and Blavatsky even asked Countess Wachtmeister to initiate a similar scheme in London.[18]

Judge gave her a warm smile. He did not care for the attention but understood Julia’s gesture for what it was—sincerity.

“Before Brother Sattay gives his talk,” said Judge, “I wish to read a letter that I recently received from our Brother Dharmapala of Ceylon.”

Ceylon, Colombo, August 14, 1888.

Mr. William Q. Judge.

General Secretary, Theosophical Society, New York.

Esteemed Brother:—We are thankful to you for the occasional announcements that you make in The Path about the work of our Society in Ceylon. No other Society of Western origin in Ceylon has ever been so popular as that of ours, and no other Society has done so much good within these few years as ours. This ought to make you glad, for you were one of the founders of the Parent T. S. The Society has been a beacon light to shipwrecked souls. It has led them to think of the incalculable importance of unselfish work. The few devoted souls who are working in its interest have received much encouragement from unseen quarters. The progress of the Society has been gradual, and at the same time steady. The work that we have in view is of enormous magnitude; little has been done and much remains to be done. The most important work that we have commenced is the establishment of schools for the education of our boys. Hundreds of addresses have been delivered in almost every town and village in stirring up the Buddhists by our beloved President, and the nucleus of a National Fund was created by him. About £1,000 have been collected and deposited in the Bank. For the accomplishment of this great work a sum of £25,000 is required. How shall we be able to realize this grand object? Our little island cannot arise this amount, and we have to appeal to our Buddhist Potentates and sympathizing co-religionists of all countries for help. Christian Missionaries are trying their best to undermine our religion, and they succeed in making converts of our people. Christianity has been the bane of Ceylon. It is re sponsible for the crimes that are being committed in Ceylon by our people. Vice and drink were unknown in Buddhist Ceylon, and the historical records testify to this assertion. With the advancement of European civilization crime of course increases.

Our beloved colleague, Mr. Leadbeater, permanently resides in Ceylon, and his presence is of the greatest use to us. We want two or three more European Buddhists to keep up with the increasing work. I have sent a copy of the specimen of the “Buddhist” (magazine) which we hope to bring out in November. The “Sarasavisandaresa” is the organ of our Society, and the Buddhist will be published as a supplement to the above Paper. There is plenty of work to be done, in Ceylon, and we would gladly welcome willing workers. I ask your sympathy and your co-operation to the good work that we are doing for the dissemination of the life-giving and soul-consoling dharma of the Tathagato.

Invoking the blessings of the Lord, the Law, and the Order, I am ever yours,

Sincerely,

Dharmapala Hevavitarana,

Assistant Secretary, T.S. (Colombo.)[19]

Having concluded the preliminaries of the meeting, Sattay began his talk.

“I know that very few Christians have sufficient knowledge of the institutions of the Hindu caste system, and I therefore shall try to give some particulars. Sanskrit books give four distinct combinations of the whole mankind—not Hindus alone—the Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra in order.”

Though educated in the modern fashion at the College of Madras, Sattay never abandoned the traditions of his forebears. He prayed twice a day, kept a strict vegetarian diet, and wore the Upavita, the sacred cord which Brahmin men wore after coming of age.[20] Having learned seven languages, public speaking was not one of his weaknesses. Beginning his career as an accountant in Madras, after the death of his wife, when their son was just a baby, Sattay moved to Calcutta and entered the Postal Service, but, with regards to money, he was not what one would call ambitious.

“The ingredients of the first combination,” Sattay said, “being of a superior nature, the Brahmin were naturally inclined to read, and understand, the word of God, called the Vedas, and thus became the priests and guides of the lower orders.

“The Kshatriya,” Sattay continued, “were made of harder stuff, and were consequently the warrior classes.” The duty of the Kshatriya, as Joshi once explained it, was to protect the Brahmins, relieve the oppressed, suppress the wicked, and aid the weak.

“The other two classes were subdivided into several orders, and each order was peculiarly adapted to some particular profession. Thus, from ages to ages, the several classes in India followed the same profession.” Sattay paused for a moment. “The father used to teach his son the particular, and the son was always the wiser than the father. In short, our merchants, carpenters, barbers, tailors, goldsmiths, blacksmiths, and all sorts of smiths, even the washermen and shoemakers, have all been in their own hereditary professions, and if anyone should change his trade for that of the other, he was considered to be an ‘out-caste’ by his castemen. Intermarriages were prohibited by strict rules, and if any man or a woman should be found illegally attached to each other, they were despised and hated as fallen persons. In this manner, from the highest priesthood to the lowest shoemaker, caste system had its full sway, and there were few cases of exceptional genius born in the lower orders, or dull-heads among the higher classes. The breed was kept up, and the fruit was always true to the seed.”

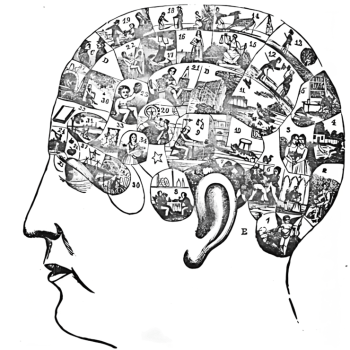

“The Hindu philosophy of transmigrations of the soul is in keeping with the caste system, and it accounts for the various combinations of the human body. God created them, and man had to keep them up in obedience to His rules set down in the Vedas. Men that transgressed those rules were considered as mlachas, or the fallen, and hence the population of other countries is found in the most chaotic order. However, the natural tendencies of each man, of whatever nationality or country he may be, is found to be adapted to a particular profession alone he thrives and is at full peace of his mind. Boys of the same class, who receive the same sort of training, are found in their manhood quite differently engaged from each other; some of them the most virtuous and pious of men, while others the perpetrators of the foulest crimes.

“Can you deny that the material of which each man is made is peculiar to himself, and is the product of his own acts? Otherwise what makes one, though poor, happy and healthy, while the other, though wealthy, yet filthy and miserable?”[21]

Judge saw Julia discreetly rubbing her in head. He knew that she was given to visions, but also suffered from crippling migraines. She belonged to that school of occultism that believed that “spiritual powers should never be used for personal benefits of any kind,” and preferred suffering over removing the pain.[22]

“Mr. Sattay,” asked a fellow member, “can you explain why Hindus abstain from meat?”

“The Hindu religion enjoins one to be kind and merciful to all living creatures,” Sattay replied. “To put to death any creature that has life is an unpardonable sin to a Hindu, while to protect it is one of the highest virtues. Beasts, birds, reptiles, and insects are as much the object of the Hindu’s kindness as humankind. Hindus of the higher castes never take flesh. They live entirely on milk and vegetables. Hindus of certain sects take meat, but they would not eat it unless it be of a goat, sacrificed before a god or goddess. They would never think of shooting a bird or killing a beast.

“The look upon the European practice of shooting and hunting as barbarous. They distribute rice and corn to crows and other birds every day. India is the land of snakes, most of them being of the most venomous kind. But the Hindus are not less warm in their kindness toward these creatures. Snakes that have taken shelter in a Hindu’s house are never killed by the inmates. They are regarded as guests and allowed to wander in the house unmolested and untouched.”

After Sattay finished he quietly took his leave. The other members, likewise, began to disperse. Judge approached Julia.

“Is everything alright?”

“Will,” said Julia, “I saw death in his face.”

“Sattay is always thin and grave,” said Judge.

“I do not judge from externals. It is a terrible hollowness that I felt. It is as though a cold cloud envelops him.”[23]

← →

THE AGONIZED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS: “ACT II”

I. THE LITTLE TOY TEMPLE ON NASSAU STREET.

II. UNION OF HEARTS.

III. IN DARKEST LONDON.

IV. NONSENSE OF BROKEN TEACUPS.

V. A CURIOUS REUNION ON WALNUT STREET.

VI. GLORIFIED IN THE LAND OF BABYLON.

VII. ALWAYS THIN AND GRAVE.

VIII. ET IN ARCADIA EGO.

IX. THEORY OF UTILITY.

X. APOLLO BUNDER.

XII. THE SILENT PASSENGER.

XIII. DECCAN PLATEAU.

SOURCES:

[1] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III., No. 7. (October 1888): 235-236.

[2] “Age of Strife.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts.) April 27, 1891; “Mrs. Besant And Mr. W.Q. Judge On ‘Theosophy.’” The Birmingham Daily Post. (Birmingham, England) June 30, 1891.

[3] “Old Cambridge.” The Cambridge Chronicle. (Cambridge, Massachusetts.) February 17, 1894.

F.T.S. “Questions And Answers.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XVII., No. 4. (April 1920): 395-397.

Hargrove, Ernest Temple. “Letters From W.Q. Judge.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXIX, No. 1. (July 1931): 35-44.

[4] The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. “Madison Square, N.Y” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1893. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-d7ea-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

[5] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III., No. 7. (October 1888): 235-236.

[6] “Shade of Sattay.” The Independent Record. (Helena, Montana) November 22, 1888.

[7] Keightley, “Tea Table Talk,” The Path, (December 1888): 293-297.

[8] Ver Planck, Julia Campbell. The Wonder Light and Other Tales for Children. The Path. New York, New York. (1890); Ver Planck, J. Campbell. “A Theosophical Catechism.” The Path. Vol. V, No. 7. (October 1890): 213-217; Ver Planck, J. Campbell. “A Theosophical Catechism.” The Path. Vol. V, No. 8. (November 1890): 249-252; Ver Planck, J. Campbell. “A Theosophical Catechism.” The Path. Vol. V, No. 10. (January 1891): 304-307.

[9] “The Stage.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.) February 19, 1884.

[10] “Madison-Square Theatre.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) May 24, 1885.

[11] May, Caroline. The American Female Poets with Critical Notes, Lindsay & Blakiston. Philadelphia, Pa. (1848.):485; “J.H. Campbell.” The Chicago Tribune. (Chicago, Illinois) April 13, 1895; Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. “Campbell, James Hepburn (1820-1895).” Accessed July 20, 2020. https://bioguideretro.congress.gov/Home/MemberDetails?memIndex=C000088.

[12] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3646. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) J. Campbell Ver Planck. (5/27/1886); “Two Loyal Friends.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XIII, No. 3 (January 1916): 220-224.

[13] Ancestry.com. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S., Death Certificates Index, 1803-1915. [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011; Norbury, Mackenzie George; Rhoades, Nelson Osgood (eds.) Colonial Families of the United States of America. Vol. I. Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc. Baltimore. Maryland. (1995): 549.

[14] “April 29, 1886—Dear Friend.” in Judge, William Quan, and A. L. Conger. Practical Occultism. Theosophical University Press. Pasadena, California. (1951)

[15] Ver Planck, Julia C. “End of Our Third Year.” The Path. Vol. III., No. 12 (March 1889): 369-370.

[16] “Notice—The Path.” The Path. Vol. III., No. 8. (November 1888): 267-268.

[17] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III., No. 7. (October 1888): 235-236.

[18] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III., No. 8. (November 1888): 259-264.

[19] “Correspondence.” The Path. Vol. III., No. 7. (October 1888): 233-235.

[20] “Ashes Not Scattered.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) December 31, 1888; Hastings, James (ed.) Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics: Vol. II. Charles Scribner’s Sons. New York, New York. (1910): 407.

[21] There is no written record of Sattay’s talks. The dialogue is taken from editorials written by Sattay when he was a correspondent for the Weekly Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) and reprinted in other publications. [“From A Hindoo.” The Richmond Dispatch. (Richmond, Virginia) July 12, 1885; “Hindoo Kindness To Animals.” The Knoxville Daily Chronicle. (Knoxville, Tennessee) November 8, 1885.

[22] Lovell, John W. “Reminiscences Of Early Days Of The Theosophical Society.” The Canadian Theosophist. Vol. X, No. 5 (July 15, 1929): 132-136.

[23] Keightley, Julia. “Tea Table Talk.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 9. (December 1888): 293-297.