SPIRITS BRIGHT AND AIRY

ACT II.

XIV.

⸻

Judge took one last look around the rooms of 10 Talbot Street. Before the home passed on to his late uncle, Samuel Quan, it belonged to the man whose namesake he bore, his maternal grandfather, William Quan, the coachmaker. Closing the door, Judge walked into a morning saturated with mist. He glanced north in the direction of the Docklands, and briefly considered visiting his childhood home at 36 Seville Place.

“I have seen ghosts ever since I was a boy,” Judge thought to himself.

The yawny Sun made brief appearances in November, and as he had an engagement with some new Irish Theosophists later that evening, he thought it best to be on his way.

He was soon at the Liffey, a murky river imprisoned on either side by a thick granite wall. Ellipses of parapets dotted the length of the river with iron gates, and stone steps which lead to the water. From the commanding position of O’Connell Bridge, Judge enjoyed the majestic, yet simple, beauty of the several other bridges which stitched the land together.[1]

Once on the other side, Judge approached a hungry-looking young girl who carried a basket of flowers.

“Young miss,” he said, “how much for the hyacinths?”

“Sixpence a dozen, sir,” said the girl. “It’s a fair price, sir. They’ll surely make the missus happy.”

Sackville Street.

He smiled at the girl while he fished the coins from the pockets his overcoat. By his estimation, the flower-girl was no older than thirteen. She was just about the age of his daughter—if his daughter was still alive.

“Thank you,” said Judge, handing her the coins.

“Thank you, sir!”

Judge turned to walk away.

“American or Irish?” the girl asked.

“American,” said Judge. “Brooklyn.”

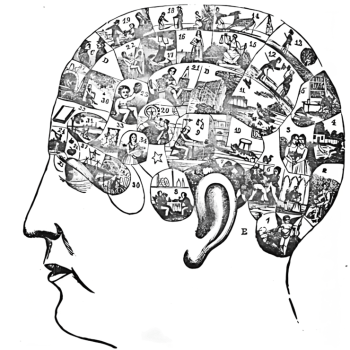

Continuing along Wicklow Street, Judge did not stop again until he arrived at Goldsmiths’ Hall. Judge gazed into the faces of the latest models of chronographs displayed in the shop window.[2] He recalled an old Hindu proverb: “He who knows that into which Time is resolved, knows all.” He then remembered Sattay’s Sanskrit lessons. Time was Kāla—the destroyer and renovator. “Cycles,” Judge thought to himself. “Years roll into centuries, centuries into cycles, and cycles become ages. But Time reigns over them all.”[3]

William Quan Judge.

Many years earlier, his father, Frederick Judge, worked as a clothing merchant on the spot which Goldsmiths’ Hall presently occupied.[4] Though never wealthy, Frederick was able to house his family in the modest rooms in the Docklands, the “very poor locality,” on the fringes of the city. It was there where Judge was born on April 13, 1851, the third of Alice Mary Judge’s six children.

Trinity College.

The sound of breaking glass drew Judge’s attention to a nearby vacant building. Some young men were throwing rocks at what remained in the panes.

“Just like the peasants,” a passerby was heard saying. “They cling to their superstitious beliefs in fairies, ghosts, and the like.”

“And why shouldn’t they, eh?” said his companion. He was a man from nearby Trinity College by the look of his dress. “Do you want the devil to stay in the house?”[5]

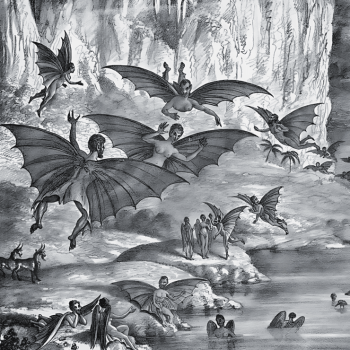

The prevailing theory was that the spirits of the departed tenants, which Judge named “elementals,” could only escape through the broken windowpanes.

“Erin’s Isle has always been somewhat of a mystery,” Judge thought. “Its people are so different from the English just across the channel that anyone who spent some time in London—and then crossed over to Dublin—would at once see the vast gulf that, in the matter of temperament, separated the two peoples. Anyone who lived among them, would soon discover a deeply-seated belief in what was commonly called the ‘supernatural’ that can only come from some distant past.”

A memorable incident from his own youth illustrated his point. It occurred during the year of 1858 when living conditions in the “Docklands” had incrementally improved. The abandoned homes on Beaver Street were replaced with new ones. The ruins of the vinegar works on Sheriff Street and the dilapidated structures of the environs were demolished. For young Judge, however, the rehabilitation of the ward arrived too late. After developing mysterious symptoms, he slipped into a prolonged and debilitating illness which nearly killed him. He eventually recovered, but having tasted death, he was forever a “changed lad.” He soon developed an interest in religious works, philosophy, myths, and magic, and sacred legends.[6] Some believed that the suffering “had opened some door in the heart of the boy, through which he caught some inkling of a great purpose which lay ahead of him in life.” It was then that he began to share his body with the Rajah—but he told very few people about this detail.[7] “A vow once made is to be fulfilled,” thought Judge, “and Father Time eats up all things and ever the centuries.”

It was still morning when Judge arrived at the townlet of Harold’s Cross where the Cemetery of Mount Jerome was located. A former demesne of the Earls of Meath, Mount Jerome was now a burial ground devoted (almost exclusively) for the use of Protestants of every denomination.

Mount Jerome.

When he reached the Quan family plot, Judge said a prayer over the grave of his uncle.[8] In reverential silence he approached a neighboring grave. Kneeling down, he gently placed the bouquet of hyacinths in front of the tombstone which read:

Alice Mary Judge.

1821-1860.[9]

Months after Judge recovered from his childhood illness, his mother died in childbirth in the family home. It was one day shy of her wedding anniversary.[10] The wraith of a melancholic expression began to manifest beneath Judge’s beard, but the happier memories of his mother prevailed, and they bested the aggression of his woe.[11]

The sky rustled as the autumn wind slithered through the trees.

“I have seen ghosts ever since I was a boy,” Judge thought. “My mother, being dead, appeared at my bedside and looked down on me.”[12]

← →

THE AGONIZED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS: “ACT II”

I. THE LITTLE TOY TEMPLE ON NASSAU STREET.

II. UNION OF HEARTS.

III. IN DARKEST LONDON.

IV. NONSENSE OF BROKEN TEACUPS.

V. A CURIOUS REUNION ON WALNUT STREET.

VI. GLORIFIED IN THE LAND OF BABYLON.

VII. ALWAYS THIN AND GRAVE.

VIII. ET IN ARCADIA EGO.

IX. THEORY OF UTILITY.

X. APOLLO BUNDER.

XII. THE SILENT PASSENGER.

XIII. DECCAN PLATEAU.

SOURCES:

[1] Wakeman, William Frederick. The Tourists’ Picturesque Guide to Ireland. The “Official Guide” Ltd. Dublin, Ireland. (1889): 73.

[2] Stratten & Stratten. Dublin, Cork, and South of Ireland: A Literary, Commercial, and Social Review. Stratten & Stratten. London, England. (1892): 13; 17.

[3] Judge, William Quan. “The Magic Screen of Time.” The Path. Vol. IV, No. 1. (April 1889): 10-13.

[4] Thom, Alexander. Thom’s Almanac and Official Directory of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Vol. XXVI. (1859): 1321; “Novelties.” The Dublin Evening Packet and Correspondent. (Dublin, Ireland), April 29, 1861.

[5] Judge, William Quan. “Ireland.” The Path. Vol. VI, No. 11. (February 1892): 331-332.

[6] Hargrove, Ernest Temple. “Letters From W.Q. Judge.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXIX, No. 1. (July 1931): 35-44.

[7] Niemand, Jasper. Letters That Have Helped Me. Vol. II. The United Lodge Of Theosophists. Los Angeles, California. (1920): 100-106.

[8] “Find A Grave Index,” database, FamilySearch. 11 August 2022), Samuel Quan; Burial, Harold’s Cross, County Dublin, Ireland, Mount Jerome Cemetery and Crematorium; citing record ID 240822106.

[9] “Ireland Deaths, 1864-1870,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:HP6V-GVW2 : 5 February 2020), Alice Judge, 1860.

[10] Dublin Almanac and General Register of Ireland. Pettigrew & Oulton. Dublin, Ireland. (1847): 565; “Deaths.” The Dublin Evening Packet and Correspondent. (Dublin, Ireland), March 3, 1860.

[11] “Personal Points.” The Kansas City Times. (Kansas City, Missouri) March 10, 1887; “Old Cambridge.” The Cambridge Chronicle. (Cambridge, Massachusetts.) February 17, 1894.

[12] “Touched By Ghosts.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) October 15, 1894.