THE LITTLE TOY TEMPLE ON NASSAU STREET

ACT II.

I.

⸻

On September 25, 1888, William Quan Judge sat with his fellow Theosophists in a room in handsome brick mansion at 64 Madison Avenue.[1] Mott Memorial Hall was the room rented on specified Tuesday nights for the regular meetings of the Aryan Branch.[2] It had a special meaning for Judge, as Mott Memorial Hall was where the inaugural address of the Theosophical Society was delivered by Olcott in 1875.

Judge looked about at the menagerie of medical oddities in the room, bequeathed by the late Dr. Valentine Mott, the namesake of the hall.[3] “A curious antithesis is found in the fact that the Microscopical Society meets here also,” Judge thought. “Two great ideas, exact opposites, are investigated here, the microcosm and the macrocosm.”[4]

Mott Memorial Hall & Brownstone Row.[5]

The speaker that evening was Govindarao Sattay, who formally joined the Society three days earlier.[6] His talk was titled “Jesus as a Theosophist.”[7]

Though Sattay only just joined the Society, his history with the group went back as far as 1883, when he still lived in India. Forsaking his Brahmin caste, he arrived on American shores in 1884 and quickly went to work down South to learn the “industrial arts.” In the summer of 1886, Sattay was arrested in Ocean Grove, New Jersey, on blasphemy charges, as he condemned the practices of Christian missionaries in India. Judge, deftly using the power of the press, leveraged public opinion against the imprisonment, and made something of a martyr out of Sattay.[8]

When he was released from prison, Sattay took a job Charles Eisenmann’s photographic printing factory, at 543 East Fifteenth Street in Manhattan.[9] In 1887 Sattay moved to 227 Duffield Street, Brooklyn, just 500 feet from Judge’s own residence on 116 Willoughby Street.[10] The close proximity allowed the men many opportunities for discussions on spiritual matters, which both of them enjoyed.[11] Sattay continued working at Eisenmann’s factory, while also tried his hand (unsuccessfully) at business by introducing Indian ceramics and perishable articles into the New York market.[12] Nevertheless, Sattay was able to create a modest savings from his work at Eisenmann’s, this was accomplished by living on nothing but bread and milk for an entire year.[13] The Great Blizzard of 1888 took its toll on Sattay, who experienced a decline in health. (He was bed-ridden for most of the month of April.)[14]

New York in the blizzard of 1888.[15]

Sattay was devoted to the cause of Indian liberation and proposed to use all the money he had in this endeavor. Though he was ill, he dauntlessly carried on with this singular aim. When his friends expressed their concern that Sattay was over-extending himself, he replied: “I think patience and perseverance will enable me to carry out my scheme.”[16] To this end, in the summer of 1888, Sattay helped facilitate the importation of the entire consignment of Tukaram Tatya’s Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali (as well as Sanskrit texts, and other works of a spiritual nature) to America.[17]

He was dying, seemingly from tuberculosis, though no one knew it at the time, perhaps not even himself, as he was about to form a Sanskrit class among the students at Columbia College.[18] He spent the summer of 1888 in Saratoga, New York, where he continued giving talks on the British in India. The “morals and habits of the [Indian] people,” were corrupted under British rule, he stated, and the people of India now indulged in “excesses formerly unknown to them.”[19] While there, he attended the meeting of the American Social Science Association on September 3, 1888. “The enthusiasm of his listening” was indicated by his “glowing eye.”[20] When he returned to Brooklyn, he told Judge that he intended to devote a year to “working entirely for the Cause […] whether in free teaching of Sanskrit, in expounding Oriental Scriptures from his standpoint as a Brahmin and a Buddhist, in giving lectures on India or on psychic or literary topics, in a word, all that he could do.” His gratitude toward Judge and the Theosophists inspired him with a single aim, and towards it he endeavored to work with the entirety of his soul.[21]

He was clearly ill, however, and this troubled Judge.

“Sattay, you should rest,” Judge told him after the talk. “Go down South—the warmer weather will do you some good.”[22]

“I do not wish to remain idle,” Sattay replied. “I plan on delivering lectures this winter at any Branch of the Society that sponsors my travels.” [23]

~

Day after day Judge held Theosophical Society meetings in his law office in the Vanderbilt Building at 117 Nassau Street. Day after day he sat there “thinking and wishing for somebody to come in.”[24] So, Judge devised a plan to draw people in by securing Room 45 (the room next to his office) to serve as a Theosophical Headquarters.[25]

Vanderbilt Building (after 1890s extension.)[26]

It would also serve as a “Buddhist Temple,” the first of its kind in New York. “It is not a great building, such as the devotees of this faith have long intended to build on Fifth Avenue,” the papers said, “but it is nonetheless a temple, duly consecrated.” The papers acknowledged that “the Chinese residents have established joss houses” in New York, in which they “worship after their particular forms, which are after a fashion Buddhistic,” but this, “according to the belief of India,” was “not Buddhism.” The Theosophical Buddhist Temple, was “of the real Indian kind.”[27] To get people to visit the “Temple,” Judge by “[filled] it with idols and barbarian smells so as to strike awe to the visiting beholder.”[28]

In little over a month, Max Müller would address the question as to whether or not Buddhism was even a religion.[29] As for his bona fides, Judge was taken into the Ceylonese “Church [Buddhist]” over which the monk, Sri Sumangala Thera, presided, while in India in 1884.[30] Though Judge did not practice a form of Buddhism that was easily recognizable by traditional Buddhists, his contribution to spreading the tenets of that faith in America were recognized far and wide.

~

Judge ran with a circle of friends that included colleagues from City Hall, and reporters from nearby “Printing House Square,” such as David A. Curtis, Edward Page Mitchell, Frank Church, and James “Jim” Henderson Connelly. Judge would attend poker nights with the journalists, where he earned the nickname “The Adept,” because of his “undoubted skill at the game.”[31] Of these men, Judge was closest to Curtis and Connelly, and as the “temple” was located conveniently near “the newspaper gang in Printing House Square,” the local papers were soon “busily engaged in working up the Theosophical Society of New York [and Buddhism] into a sensation.”[32]

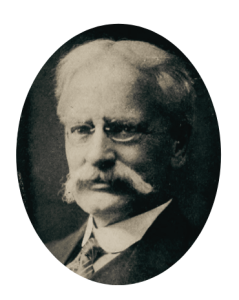

Curtis, in addition to being a reporter, was also an early member of the Society.[33] Born in Norwich, Connecticut, on October 19, 1846, Curtis was educated at Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute and Columbia Law School. A reporter, writer, editor, and contributor to nearly all of the New York newspapers and magazines, he was considered an authority on the Bowery and other noted Manhattan streets.[34] Curtis’s pen played no small part in popularizing the “character” of Madame Blavatsky in the early days in New York. It was Curtis, after all, who named Blavatsky and Olcott’s shared apartments on 47th Street and Eighth Avenue, “The Lamasery,” after “the sacred colleges of Thibet, where acolytes are trained in the mysteries and sacred rites of Tibetan theology.”[35]

David A. Curtis.[36]

It was through Curtis that Judge first met Jim Connelly. It was on March 20, 1878, when Curtis convinced Judge, Blavatsky, and Olcott to investigate the ghost of “Old Shep” at the East 39th Street Pier.[37] The former managing-editor of The New York Herald, Connelly was born in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania in 1840, and became a reporter for The Pittsburgh Chronicle while still a youth.[38] In 1857 he went West to be a reporter for The Cincinnati Columbian, and Chicago Tribune, and in 1858 returned East to report in New York where he worked on nearly every leading paper. He took a hiatus only during the Civil War in which he served in the 145th New York Volunteers. In 1872 he married Celia Logan, an author who studied under Charles Reade.[39]

In 1886, just after Sattay was released from Freehold prison, David A. Curtis published an article in The Sun titled “Buddhism in New York.” As Curtis stated: “The Buddhist faith [was] gaining ground in New York and Brooklyn to an extent not dreamed of by the Average Christian.” The article stated that “another year, it [was] predicted, there would be a Buddhist temple in New York, where mystic truths will be taught by Brahmins and the sacred books of the East will be expounded to initiates.”[40] Curtis also built on the mythology of the Theosophical Society. “The story goes that two years ago a mysterious visitor came here from Central Asia to see and instruct some of the more advanced pupils,” wrote Curtis, “and several were authorized to teach and initiate others.”[41] He was referring to the “mysterious Hindoo,” a “messenger of the Society,” who appeared in New York in 1884 to initiate the Aryan Branch. After reading a passage from the Mahabharata, he gave Abner Doubleday (acting President of the Aryan Branch at the time) a copy of the Bhagavad Gita before he “mysteriously disappeared.” Some of those present that night “recognized him as the man present at the cremation of Baron de Palm and the ceremony in November 1878.”[42] And by this he meant the unnamed Hindu who assisted in the cremation ceremony of Baron de Palm, and the subsequent Vedic ceremony in which de Palm’s ashes were caste into the Hudson River near Governor’s Island. When the boat returned to the pier, the Hindu, without a word of farewell, disappeared in the darkness.[43] As Curtis was present at the Vedic ceremony, and (presumably) the creation of Aryan Branch, one might be inclined to believe that this “character” was invented for a sensational article. Blavatsky, however, corroborates Curtis’s claims. In her diary entry for November 22, 1878, she wrote: “Our mysterious Hindoo Brother […] was present with his helper.”[44]

Whatever the case may be, Curtis’s 1886 “Buddhism in New York” article gained immediate attention. The announcement that New York was to “have a place of worship or public meeting for the rapidly growing Buddhist societies” created much interest. As a consequence, the regular Tuesday meeting of the Aryan Branch held after the publication of the article, “was attended by strangers seeking the names of the officers and wanting information relative to the matter [of Buddhism.”[45] A week after this article, “Brooklyn Buddhists” was published in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, which named Judge as “the President of the Aryan Theosophical Society in New York, editor of The Path and leading spirit and instructor of the Buddhists of Brooklyn.”[46] The article was attributed to “Recluse” but was most likely written by Judge’s friend, the Theosophist, Laura C. Holloway, author of The Buddhist Diet Book (1886,) who was on the editorial staff of The Brooklyn Daily Eagle.[47]

Some 1886 articles about Buddhism in the New York newspapers.

Curtis and Connelly left the newspaper business not long after the article. At the time a man named Austin Corbin, of the Arrow Steamship Company (A.S.C.,) thought of a scheme that would connect the Long Island Railroad with a fleet of swift ocean steamers that would cut a day off the transatlantic trip.[48] The company was going on with “small capital and large prospects.”[49] Connelly and Curtis joined the A.S.C., Connelly on the Executive Committee, and Curtis taking the position of Corresponding Secretary.[50] They were in the business “up to their eyes,” but “were enthusiastic to a most enjoyable degree.”[51] Their former employer, The New York Herald, made a tremendous attack on the A.S.C. with a series of damning articles which charged the company’s officers with being “conspirators,” “confidence operators,” and “swindlers.” This was a “very black eye for the company.” The company went under, and the former reporters found it difficult to go back into their former profession.[52] In late 1888, they decided to take the Herald to court for libel, Curtis, and Connelly each sued for $50,000, while the company itself sued for a million.[53] In the meantime, both men took work writing freelance articles for other publications like The Sun.

Curtis’s articles about of Buddhism’s growing appeal in New York gained international attention in 1886, with articles about it appearing in newspapers as far away as Russia.[54] One such article, published in Russian News, was read by a Japanese Buddhist scholar named Matsuyama Matsutaro. Intrigued by the American Buddhists, Matsuyama sent a letter to Judge to learn more about the movement. The letter said in part:

We beg your permission to take the liberty of writing this letter to you. We are the followers of Buddhism in Japan; and we learned lately from a Russian news that there are some Buddhistic followers in the United States. N. A., particularly in New York and Brooklyn, and that the application of the new converts are to be made to your Society; it is very strange to hear that there are some Buddhistic followers in your country, adding the new converts to their number. If this statement of the news be all right, we shall have a great pleasure of having Buddhism spread among the whites, such as the people of the United States, and are very desirous to hear some detailed statement about the things from you.[55]

Judge quickly replied:

The account you read in the newspaper was in part true. There is no temple in this country. But there are many Buddhists. They do not properly understand it however, because there are no teachers, and many wicked lies are told against Buddhism by Missionaries and other people. The people need that religion because their own has not succeeded in making them honest or kind to each other. They are always fighting and going to law with each other although Jesus their prophet told them not to do so, but to love one another, and although they are not very happy, because the illusions of life make them slaves of the senses. So do tell your young men not to desert the law of Buddha for this religion but to try to spread Buddhism again over the face of the world.[56]

In these correspondences, Judge requested that a preacher of Buddhism be sent to America, “as people there wanted to learn it.” Through Judge, Matsuyama would be introduced to other Theosophists, like Olcott, which forged important links. Judge’s letters were subsequently published in Matsuyama’s journal, Hansei-kai Zasshi, in the column “Ōbei Tsūshin (Correspondence from America and Europe.)”[57] In July 1887 Judge received another letter from Matsuyama. It said in part:

I am very glad to receive your epistle, answering to us: I have taken a great pleasure to read in it, that the story we read in the Russian News, is in part true; and I am much interested of your earnest efforts of spreading the pure truth of Buddhism. […] Some missionaries from France, England, the United States, and Russia, are endeavoring to Christianized this country but for present their followers are few, and the influence of their religion is very weak upon our society. Our young Buddhistic men, particularly those of the Shin sect, exhibit a strong spirit to propagate the truth of the great law over the face of the world, and they are making preparation in learning English and other languages. I have translated your letter, and inserted to some of our news, and I believe that it has made an interesting impression on our Buddhists.[58]

The month before Judge opened the Buddhist Temple on Nassau Street, Matsuyama published the first issue of the Japanese Buddhist journal, The Bijou of Asia.[59] Judge contributed an article in which he gave a “gloomy sketch of Western morality in justification of his opinion that ‘the religion of Buddha [was] much needed.’”[60] In the September 1888 issue of The Path, Judge published an article, “A Buddhist Doctrine,” based on the literature that Matsuyama had sent him.[61]

~

Construction on The New York Times Building, August 1888.[62]

The sound of hammers striking iron, granite, and Indiana sandstone were heard by Judge and Curtis as they entered 117 Nassau Street. Work had begun on the new building of The New York Times at 41 Park Row. From what they could see, the work was progressing nicely. The first beams were in position on the lines of the adjacent buildings, and all the stonework was set (except the dormer on Nassau Street.)[63]

After walking up the four flights of stairs, they entered Judge’s office. There they were met by an Indian man who, in Curtis’s estimation, was “immeasurably more emaciated than any other human being outside of a dime museum hot a right to be.” This man, who went by Balarama Narayana Peit. A noticeably “strange odor” reminiscent of sandalwood, floated in the air around him. His garb was a compromise between native costume and the clothing best adapted to the American climate. Over what looked like a ready-made suit from a Broadway clothier establishment, he wore a long blue coat of no particular pattern—just a coat, and on his head was perched a Poona turban.

Curtis was unaware of any Indian in the Aryan Branch, aside from Sattay. Then again, Curtis never met Sattay—the thought crossed Curtis’s mind that perhaps Judge was pulling wool over his eyes.

“Balarama,” said Judge, “is on a mission from the Mahatmas, and will disappear when that mission was accomplished.”[64]

Behind the door which separated Judge’s office from the “temple,” there was Persian curtain of great beauty. Pushing this aside, Curtis saw, opposite the doorway, a small, Burmese, cross-legged statue of Buddha in a little niche. There is sat “pondering the inexplicable secrets of nature as imperturbably as he would if stationed in a Mahatma’s cave.” In front of him there was a pot of incense that was kept continually burning; the smoke rose in curly wreaths and filled the air with a stilling perfume. Beneath the statue, fastened as a dado, was a Ceylonese grass mat that Judge brought from India when he returned to New York in 1884.[65]

“The New York Buddha.”[66]

At the end of the room, over the one window, the seal of the Theosophical Society occupied a place of honor. Over it was pictured, in illuminated letter, the motto: “No religion higher than truth.” It was intended to have an icon representative of “all the great religions,” but “Brahmanism and Buddhism” were the main features. Among the other religious emblems to be found was a small silver medal of the Virgin Mary, blessed by Pope Leo XIII, that hung on the wall—but it was so small, that most failed to take notice.[67]

“Some of the pictures on the walls are not easily found elsewhere,” said Judge. “There are many Indian ones representing Krishna and others, and two pictures from Poona are quite curious. They are cut out of white paper by hand, and, by placing colored paper underneath, the design was seen.”

Curtis leaned in for a closer look at the Theosophical Society Headquarters in Adyar, India.

“Some Theosophists think there is no need for a headquarters of the Society,” said Judge, “neither in India nor in the United States, and that the money spent for maintenance of such centers ought to be devoted to some other object. I disagree with this view. The buildings and grounds belonging to the Society in India are our only headquarters, strictly speaking, and are desirable, while centers of theosophical work elsewhere have fully demonstrated their usefulness. Adyar, the ‘center’ in India, has done the greatest good to the Society. It is visible evidence of our work and influence, and, as such, a point not only of interest for Theosophists, but of serviceable impression upon others. While we are working in the world, we must use the things of the world, and not attempt to drag everyone, whether or not, to the high planes of thought where there no longer is any necessity for tangible evidences. Nothing encourages people so much as results of work, and in our struggles with the scoffers we often find assistance in that we are able to point to where outward signs could be found for that which we have tried to do. The headquarters are, in one sense, the embodiment of an idea—that of Universal Brotherhood—for it was created and is supported by the efforts of members holding to every known shade of religious belief and of every race, caste, and color. The need for a similar locus standi in the United States has been felt for some time, an opinion shared by many others.”[68]

“Birds eye view of the obelisk on the left, Khylaus Cave, Ellora.” (c/o The British Library.)

There was also a drawing said to be a representation of an Indian statue of virgin and child guarded by “shadowy beings.” Judge told Curtis of a bronze miniature of the “obelisk” that stood in the rock-cut temple of Ellora would shortly to be added to the collection.

“This obelisk,” said Judge, “also bears the sculptured images of virgin and child.”

“How is the virginal character of this—undoubtedly ancient, representation—established?”

“It would be necessary for you to study many volumes of unimpeachable history before being convinced,” Judge replied.

There was a misshapen mass of rock crystal, with what looked like a “large natural faucet.”

“It varies in brilliancy at times,” said Judge. “It is a veritable magic crystal in which the spiritual-sighted can see visions, mostly relating to Theosophical matters. The officers of the Society consult it at certain times of the month to learn the condition of the branches of the Society. When only the members of the Inner Circle are present, queer sights are seen and invisible bells are heard to ring.”[69]

Around the other walls were displayed some twenty-five shields, one for each of the branches of the Society that had been established around the United States, the most active of these branch societies, or branches, being New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Iowa, Missouri, and California. These branches each had a distinctive name borrowed from Eastern religion, among them lshwara (Minneapolis,) Vedanta (Omaha,) Isis (Decorah,) and Nirvana (Grand Island.)

A heavy Turkish rug covered the floor, and plain, ordinary, furniture (store chairs and table stands) occupied the rooms. These were donations from various friends and members. [70] On the tables, as well as on the walls, there were various objects of interest. Among them were representations of the Theosophical Conventions in India, and of the Society buildings in Bombay. Another scene was the picture of an Egyptian initiation painted in magic colors, the pigments for which were dug by Blavatsky from an ancient stone wall in Tehran. Judge had carried that picture nearly all over the world. Underneath the picture was a bracket which contained “certain occult things,” a square and a pyramid of crystal and a sphere of polished steel, the use of which Judge would not explain.

On the table there a huge album containing photographs of famous Theosophists, and some not famous, from all over the world. Judge solicited such photographs in the pages of The Path.[71] The album also contained a picture of a Mahatma which was said to “wink its eyes at long intervals.”[72]

Copies, in English and Sanskrit, of the Bhagavad Gita were also on the table. It was a work which formed the basis for Theosophical discussion in America ever since Judge began writing his regular commentary on it in the April 1887 number of The Path.[73] It was a work, the first four chapters especially, had a profound impact on Judge.[74] Next to the Gita was and Tukaram’s recently arrived Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali.

“It is a valuable book,” said Judge, “but it has been an annoyance to students, since the Indian edition—the only one available—has baffled readers with the intolerable brackets and obscure notes.[75] It needs a treatment like Walker’s Reincarnation—he has an extraordinary skill in compacting ideas into the fewest and best-chosen words.[76] It need not necessarily be a translation—an interpretation of the thought of Patanjali, clothed in our language, would suffice.”[77]

“Talk to Jim,” said Curtis. “I am sure that is something that would interest him.”

Curtis picked up a visitors’ book near the works of Indian philosophy. The register of visitors showed an average of nearly two visits per day since the room was opened. Curtis found names written, among other languages, in Hebrew and Sanskrit. The names that particularly stood out to him were J. Ralston Skinner (who consulted Blavatsky for his new work, tentatively titled, Kabala the Zodiac, and the Great Pyramid of Gheza);[78] Charles Piazzi Smyth (author of New Measures of the Great Pyramid (1884,) who resigned a month earlier Astronomer Royal for Scotland);[79] Sarah Fisher Ames (an early member of the Society who was one of the first sculptors of President Abraham Lincoln); [80] and Henry B. Foulke (of the Philadelphia Branch, who joined the Society a year earlier.)[81]

~

“The most remarkable development [in Buddhism in New York,]” Curtis wrote in his article, “unquestionably, was the little toy temple at 117 Nassau Street.”[82]

← →

THE AGONIZED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS: “ACT II”

I. THE LITTLE TOY TEMPLE ON NASSAU STREET.

II. UNION OF HEARTS.

III. IN DARKEST LONDON.

IV. NONSENSE OF BROKEN TEACUPS.

V. A CURIOUS REUNION ON WALNUT STREET.

VI. GLORIFIED IN THE LAND OF BABYLON.

VII. ALWAYS THIN AND GRAVE.

VIII. ET IN ARCADIA EGO.

IX. THEORY OF UTILITY.

X. APOLLO BUNDER.

XII. THE SILENT PASSENGER.

XIII. DECCAN PLATEAU.

SOURCES:

[1] Caroline Healey Dall writes: “On the 27th of September, Sattay delivered an address before the Theosophical Society in New York, which was well received.” [Dall, Caroline Healey. “A Hindoo Theosophist.” The Unitarian Review. Vol. XXXI, No. 5. (May 1889): 397-410.] Sattay did deliver a lecture titled “Jesus as a Theosophist,” before the Aryan Branch in September. [“Theosophical Activities.” The Path Vol. III., No. 7. (October 1888): 235-236.] It was likely on September 25, 1888, however, as the Aryan Branch held their meetings on Tuesdays. [Curtis, David A. “A New Temple To Buddha.” The Brooklyn Time-Union. (Brooklyn, New York.) December 1, 1888.]

[2] Curtis, David A. “A New Temple To Buddha.” The Brooklyn Time-Union. (Brooklyn, New York.) December 1, 1888.

[3] “Mott Memorial Library Association.” The Library Journal. Vol. XIV, No. 9 (September 1889): 391.

[4] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 8 (November 1888): 259-268.

[5] Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. “Brownstone Row” New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Original

[6] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4577. (Website file: 1B:1885-1890) S. Govinda Row Sattay.

[7] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III., No. 7. (October 1888): 235-236.

[8] [“An Unconverted Hindoo.” The Sun. (New York, New York) August 26, 1886.] In a letter to Sattay at the time, Judge writes: “I saw The New York Sun about your case, and they put in an account, and now a Herald reporter wants to see you about it. I did not mean that you had disturbed their services or blasphemed but that you had committed sufficient offense for them as they own the whole of Ocean Grove and can exclude anyone they like. I thought you were injudicious for I know the temper of these bigots. Next time you will not be caught. In any public place you can say what you please but not in a place like that. You have sympathizers everywhere. I went down to Ocean Grove and found you had got out and gone away and was sorry I missed you. So, I did the next best thing which was to fully ventilate your case in the New York Sun, and it has now gone over the whole country. I will show your letter to the Herald man and perhaps he may put in some more which will give those people at Ocean Grove a good public flogging which they deserve.” [“S. Govina Row Sattay Aug. 31, 1886.” in Judge, William Quan, and A. L. Conger. Practical Occultism. Theosophical University Press. Pasadena, California. (1951.)]

[9] International Publishing Company. Illustrated New York: The Metropolis of Today. International Publishing Company. New York, New York. (1888): 126; Dall, “A Hindoo Theosophist.” Unitarian Review, (May 1889): 397-410.

[10] “A Brooklyn Hindoo Burned.” The Lancaster Intelligencer. (Lancaster, Pennsylvania) November 7, 1888; “William Q. Judge.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York) July 28, 1894.

[11] It is likely that Judge had a hand in securing Sattay’s room, as suggested in references to sponsoring a Sanskrit scholar in America in his letters to Blavatsky and Sumangala (e.g., “I guarantee to pay his passage here and back again to London, and to keep him while here,” and “I might be able to make arrangements in respect to the living here of such a person.”) [Letter: William Q. Judge to Helena Petrovna Blavatsky. September 12, 1890.] & [Letter: William Q. Judge to H.H. Sumangala. May 22, 1889.] Judge, William Quan, and A.L. Conger. Practical Occultism. Theosophical University Press. Pasadena, California. (1951)

[12] Dall, “A Hindoo Theosophist.” Unitarian Review, (May 1889): 397-410.

[13] Keightley, Julia. “Tea Table Talk.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 9. (December 1888): 293-297.

[14] Dall, “A Hindoo Theosophist.” Unitarian Review, (May 1889): 397-410.

[15] New York City Snowstorm., ca. 1888. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016652740/.

[16] In a letter to the Carpenters, Sattay writes: “My landlady was very kind to me and waited on me the whole month with more than maternal care. She is the mother of two little children and did not find it any trouble to take care of a third. All honor to the women of America! I can never forget her. I am in good health now, more vigorous than before the last sickness. It is already hot, but I can stand the heat. The mornings are very pleasant; and I enjoy the balmy hours from five to half-past seven in the park before going to the place where I have been working a year and a half.” [Dall, “A Hindoo Theosophist.” Unitarian Review, (May 1889): 397-410.]

[17] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III., No. 7. (October 1888): 235-236.

[18] “A Brooklyn Hindoo Burned.” The Lancaster Intelligencer. (Lancaster, Pennsylvania) November 7, 1888; Dall, “A Hindoo Theosophist.” Unitarian Review, (May 1889): 397-410.

[19] “People Talked About.” The Evening World. (New York, New York.) August 18, 1888.

[20] “Mrs. Dall’s Work for The Women of India.” The Buffalo Courier. (Buffalo, New York.) November 18, 1888.

[21] Keightley, “Tea Table Talk,” The Path, (December 1888): 293-297.

[22] Dall, “A Hindoo Theosophist.” Unitarian Review, (May 1889): 397-410.

[23] Keightley, “Tea Table Talk,” The Path, (December 1888): 293-297.

[24] “Mourning Their Dead.” The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco, California.) March 23, 1896.

[25] Judge, William Quan, and A.L. Conger. Practical Occultism. Theosophical University Press. Pasadena, California. (1951)

[26] Moses King. King’s Photographic Views of New York. Moses King. Boston, Massachusetts. (1895): 321.

[27] “A Temple to Buddha.” The Public Ledger. (Memphis Tennessee) November 2, 1888.

[28] See Judge’s July 10, 1888, letter to Savery, and July 21, 1888, letter to Bertram Keightley. Judge, William Quan, and A.L. Conger. Practical Occultism. Theosophical University Press. Pasadena, California. (1951); “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III., No. 6. (September 1888): 203-204.

[29] “Max Müller On Natural Theology.” The Christian World. (London, England) November 29, 1888.

[30] “William Quan Judge to H.H. Sumangala, May 22, 1889” in Judge, William Quan, and A. L. Conger. Practical Occultism. Theosophical University Press. Pasadena, California. (1951.)

[31] Mitchell, Edward Page. Memoirs Of an Editor: Fifty Years of American Journalism. Charles Scribner’s Sons. New York, New York (1924): 184.

[32] “New York’s New Religion.” The Omaha Daily Bee. (Omaha, Nebraska) December 9, 1888.

[33] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 109. (Website file: 1A: 1875-1885) David A. Curtis. (10/5/76.)

[34] “David A. Curtis, Noted Writer, Dies.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York) May 24, 1923.

[35] Olcott writes: “’The Eighth Avenue Lamasery’ was the name by which the headquarters of our Society were generally known in New York, ever since the name was given to it by the writer—one of the wittiest and cleverest reporters of New York.” [“Ghost Stories Galore.” The Theosophist. Vol. V, No. 7 (April 1884): 167-168.] Curtis writes: “Blavatsky was living in retirement working hard on the book, afterward published by Bouton. This was to be ‘The Veil of Isis,’ but when this litis was announced it was found to be already copyrighted, and the book was therefore called ‘Isis Unveiled.’ The title was unsatisfactory to the author, who declared that it was misleading as to her purpose, which was not so much to elucidate mysteries as to describe them. The announcement of the forthcoming publication attracted the attention of The World, then run by William Henry Hurlbert, and a reporter was sent to interview the ambitious woman. He was fortunate enough to win her friendship, and entire confidence, and he wrote a series of articles which, on account of their subject, attracted mention all over the world. He soon became an habitue of her house, which ho christened the Lamasery, after the sacred colleges of Thibet, where acolytes are trained in the mysteries and sacred rites of Thibetan theology.” [Curtis, David A. “Theosophists To Meet.” The Morning News. (Savannah, Georgia) April 22, 1888.]

[36] Hartwell, Stafford. Empire State Notables, 1914. H. Stafford. New York, New York. (1914): 650.

[37] Olcott writes: “Among our constant visitors was Mr. Curtis, one of the cleverest reporters on the New York press, and later a member of our Society. He made yards of good ‘copy’ out of the Lamasery […] He brought us a paper giving an account of the night-walking of the ghost of a defunct night watchman, along the wharves of a certain district on the East side of the city and begged us to go and see the phantom.” [Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume I. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1895): 332-333.] The evening in question was March 20, 1878. [“Personal Notes.” The Brooklyn Times-Union. (Brooklyn, New York) March 21, 1878; “Ghostly East-Side Sights.” The Sun. (New York, New York) March 21, 1878; “Old Sheppard’s Restless Spirit.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) March 21, 1878.] Connelly writes: “[Judge and I] first met upon an occasion when H.P. Blavatsky was induced to try, in the presence of some reporters, if she could open up communication with the diaphanous remainder of a night watchman who had been drowned in an East River dock. Olcott was present, in command, prominent and authoritative, and Judge, in attendance, reserved and quiet. The spook was shy and the reporters sarcastic. The only one apparently annoyed by their humor was the Colonel. Mr. Judge’s placidity and good nature commended him to the liking of the reporters, and made a particularly favorable impression upon me, which was deepened by the experiences of an acquaintance that continued while he lived. In all that time, though I have seen him upon a good many occasions when he would have had excellent excuse for wrath, his demeanor was uniformly the same–kindly, considerate, and self-restrained, not merely in such measure of self-control as might be expected of a gentleman, but as if inspired by much higher regards than mere respect for the convenances of good society. He always seemed to look for mitigating circumstances in even the pure cussedness of others, seeking to credit them with , at least, honesty of purpose and good intentions, however treacherous and malicious their acts toward him might have been. He did not appear willing to believe that people did evil through preference for it, but only because they were ignorant of the good, and its superior advantages; consequently, he was very tolerant.” [Connelly, J.H. “Our Friend And Guide.” Theosophy. Vol. XI, No. 3 (June 1896): 85-88.]

[38] “James H. Connelly.” The Brooklyn Citizen. (Brooklyn, New York) March 16, 1903; “School of Theosophy.” The Morning News. (Savannah, Georgia) October 8, 1893.

[39] “James H. Connelly.” The Brooklyn Citizen. (Brooklyn, New York) March 16, 1903.

[40] “Buddhism In New York.” The Sun. (New York, New York) September 26, 1886.

[41] “Buddhism In New York.” The Sun. (New York, New York) September 26, 1886.

[42] “Theosophy: A Secret Meeting Of Adherents.” The Chicago Tribune. (Chicago, Illinois.) December 5, 1883.

[43] Curtis, David A. “Baron De Palm’s Ashes.” The Sun. (New York, New York) October 20, 1878; Curtis, David A. “The Last Of Baron De Palm.” The Sun. (New York, New York) November 21, 1878.

[44] Blavatsky, H.P. H. P. Blavatsky Collected Writings: Vol. I (1874-1878.) Theosophical Publishing House. Wheaton, Illinois. (1966): 421.

[45] “A Teacher of Buddhism.” The Sun. (New York, New York) October 3, 1886.

[46] Recluse. “Brooklyn Buddhists.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York) October 10, 1886.

[47] Holloway, Laura C. The Buddhist Diet-Book. Funk & Wagnalls. New York, New York. (1886); “Women in Journalism.” The Michigan Bulletin. Vol. II, No. 10. [New Series] (December 1915): 3-5,13.

[48] “Howard’s Gossip.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) January 31, 1887.

[49] Three Big Suits Against a Newspaper.” The Post-Star. (Glen Falls, New York) October 24, 1888.

[50] United States of America. Congressional Record: Containing the Proceedings and Debates of the Forty-ninth Congress, Second Session. Volume XVIII. U.S. Government Printing Office. Washington, D.C. (1887): 2339

[51] “Howard’s Gossip.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) January 31, 1887.

[52] Three Big Suits Against a Newspaper.” The Post-Star. (Glen Falls, New York) October 24, 1888.

[53] Three Big Suits Against a Newspaper.” The Post-Star. (Glen Falls, New York) October 24, 1888.

[54] Johnston, Vera (trans.) “Letters Of H.P. Blavatsky Pt. XI.” The Path. Vol. X, No. 8 (November 1895): 235-240.

[55] Judge received a letter (probably in April 1887) from the Office of the Japanese News of Buddhism dated March 27, 1887, which read: “(Nippon Shinkio, Shinbun Sha, or Office of the Japanese News of Buddhism. Kioto, Japan, March 27, 1887.) Messrs. Aryan Theosophical Society. Dear Gentlemen: —We beg your permission to take the liberty of writing this letter to you. We are the followers of Buddhism in Japan; and we learned lately from a Russian news that there are some Buddhistic followers in the United States. N. A., particularly in New York and Brooklyn, and that the application of the new converts are to be made to your Society; it is very strange to hear that there are some Buddhistic followers in your country, adding the new converts to their number. The Russian news goes as follows: ‘Buddhism has been lately introduced into New York and Brooklyn, and its followers are very rapidly increasing in number. It is said among them that they shall build a Buddhist temple in New York. Though Brooklyn now has no Buddhist body, yet there are many scholars in a school, superintended by the present president of your society.’ If this statement of the news be all right, we shall have a great pleasure of having Buddhism spread among the whites, such as the people of the United States, and are very desirous to hear some detailed statement about the things from you; and also, we cannot help being much interested in your efforts. But we cannot readily trust in these things, as told in the news. If you will give us kindly an epistle of, we shall have a great delight. So, if we know that such as mentioned above are the real case, then we will gladly tell you about the present state of Buddhism, and other religions in Japan. Hoping for future correspondence with you, we are, sirs, yours truly, Hangio, K., Matsuyama, M., Horinchi, T.” [“Buddhism In New York.” The Sun. (New York, New York) May 22, 1887.]

[56] Judge responded: “I am a Buddhist but am not of a particular sect. I was made a Buddhist by Col. H.S. Olcott, in India, under the authority of the High Priest of Ceylon, and I try in every way to spread Buddhism…The account you read in the newspaper was in part true. There is no temple in this country. But there are many Buddhists. They do not properly understand it however, because there are no teachers, and many wicked lies are told against Buddhism by Missionaries and other people. The people need that religion because their own has not succeeded in making them honest or kind to each other. They are always fighting and going to law with each other although Jesus their prophet told them not to do so, but to love one another, and although they are not very happy, because the illusions of life make them slaves of the senses. So do tell your young men not to desert the law of Buddha for this religion but to try to spread Buddhism again over the face of the world.” [“Correspondence.” The Path. Vol. II, No. 7. (October 1887): 224.]

[57] Yoshinaga, Shin’ichi. “Theosophy and Buddhist Reformers in the Middle of the Meiji Period.” Japanese Religions. Vol. XXXIV, No. 2 (2009): 120-131.

[58] In July 1887, Matsuyama wrote back to Judge: “(Kioto, Japan, July 30, 1887.) Mr. William Q. Judge. Gentleman:—I am very glad to receive your epistle, answering to us: I have taken a great pleasure to read in it, that the story we read in the Russian News, is in part true; and I am much interested of your earnest efforts of spreading the pure truth of Buddhism. In Japan, there are the twelve sects, or schools of Buddhism, and their principles are shortly explained in the small book, A Short History of the Twelve Japanese Buddhist Sects, which I presently send to you. All the people of this country are the Buddhist believers; but, unhappy to tell, many of them are merely nominal; and the doctrines of the Mahayana school are generally recognized and respected. There are a great may teachers and monks, with few nuns, of our religion, and the temples and monasteries in this land, are numerous and splendid; some of them being really huge and grand; the photographs, which you will find enclosed along with the book, show you some of them. I have a willingness to tell you and your associates about the principles of Buddhism, as recognized in this country, but as I at present find myself busy, I will write to you about that subject, after some days. Some missionaries from France, England, the United States, and Russia, are endeavoring to Christianized this country but for present their followers are few, and the influence of their religion is very weak upon our society. Our young Buddhistic men, particularly those of the Shin sect, exhibit a strong spirit to propagate the truth of the great law over the face of the world, and they are making preparation in learning English and other languages. I have translated your letter, and inserted to some of our news, and I believe that it has made an interesting impression on our Buddhists. We are very desirous to make correspondence respecting to our religion with your associates and other people, so, I want you would kindly publish our wish. I am translating an essay, titled “A Brief Sketch of the General View of Buddhism in Japan,” and I suppose, this would be apt to make the foreign people know of the chief and central principles and dogmas of Buddhism in Japan. Sir, excuse me of the defective manner in writing. I am, indeed, a baby in English language. I am, Sir, your humble friend, Matsuyama M. Futsioco of Western Honganji (A Buddhist College,) Kioto, Japan.” [Bocking, Brian; Cox, Laurence; Yoshinaga, Shin’ichi. “The First Buddhist Mission to the West: Charles Pfoundes and The London Buddhist Mission Of 1889–1892.” Diskus: The Journal of The British Association for The Study of Religions. Vol. XVI, No. 3 (2014): 1-33.]

[59] “Literary Notes.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 5 (August 1888): 165-167.

[60] “The Buddhist Propaganda in the West.” The Daily News. (London, England) September 22, 1888.

[61] Judge, William Q. “A Buddhist Doctrine.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 6 (September 1888): 183-187.

[62] “The New ‘Times’ Building, New York—Erection of the New Structure Prior to the Removal of the Old One.” Scientific American. Vol. LIX, No. 8 (August 25, 1888): Front Cover.

[63] “The New ‘Times’ Building.” Scientific American. Vol. LIX, No. 8 (August 25, 1888): 117; “The New York ‘Times.’” Harper’s Weekly. Vol. XXXII, No. 1,662. (October 27, 1888): 818.

[64] Curtis, David A. “A New Temple to Buddha.” The Times-Union. (Brooklyn, New York) December 1, 1888.

[65] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 8 (November 1888): 259-268; Curtis, David A. “A New Temple To Buddha.” The Brooklyn Time-Union. (Brooklyn, New York.) December 1, 1888.

[66] “A Temple to Buddha.” The Public Ledger. (Memphis Tennessee) November 2, 1888.

[67] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 8 (November 1888): 259-268.

[68] “General Theosophical Centres.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 11 (February 1889): 352.

[69] Curtis, David A. “A New Temple to Buddha.” The Times-Union. (Brooklyn, New York) December 1, 1888.

[70] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 6 (September 1888): 203-204.

[71] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 6 (September 1888): 203-204.

[72] Curtis, David A. “A New Temple To Buddha.” The Brooklyn Time-Union. (Brooklyn, New York.) December 1, 1888.

[73] Judge, William Quan. “The Bhagavad Gita.” The Path. Vol. II, No. 1 (April 1887): 25-27.

[74] Jirah Dewey Buck writes: “I first met William Q. Judge in the winter of 1885. He spent Christmas week at my home in company with Arthur Gebhardt, who at that time was greatly interested in the T.S. work in America. Mr. Judge was at that time a devoted student of the Bhagavad Gita. It was his constant companion, and his favorite book ever after. His life and work were shaped by its precepts. That ‘equal-mindedness’ and ‘skill in the performance of actions’ inculcated in this ‘Book of Devotion,’ and declared to constitute ‘Yoga,’ or union with the Supreme Spirit, Mr. Judge possessed in greater measure than any one I have ever known.” [Buck, J. D. “His One Ambition.” Theosophy. Vol. XI., No. 2. (May 1896): 57-58.]

In a letter to Ernest Temple Hargrove, Judge offers this instruction: “Try to get the inner sense of Bhagavad Gita up to 4th Chapter. Put it in practice if you can every moment, and it will give great results that you really seek.” [Hargrove, Ernest Temple. “Letters From W.Q. Judge.” The Theosophical Quarterly, Vol. XXVIII, No. 4. (April 1931): 314-326.]

[75] “Literary Notes.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 12 (March 1889): 391-392.

[76] “Literary Notes.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 1 (April 1888): 23-26.

[77] Connelly, James Henderson; Judge, William Q. The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali. The Path. New York, New York. (1889): v-vi.

[78] Buck, Jirah Dewey. Modern World Movements: Theosophy And The School Of Natural Science. Indo-American Book Company. Chicago, Illinois. (1913): 40.

[79] “The Edinburgh Observatory.” The Standard. (London, England) August 17, 1888.

[80] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 35. (Website file: 1A:1875-1885) Sarah Fisher Ames. (3/29/76.)

[81] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4034. (Website file: 1B:1885-1890) Henry B. Foulke. (8/24/87.)

[82] Curtis, David A. “A New Temple To Buddha.” The Brooklyn Time-Union. (Brooklyn, New York.) December 1, 1888.