INDO-GOTHIC YOGA

X.

⸻

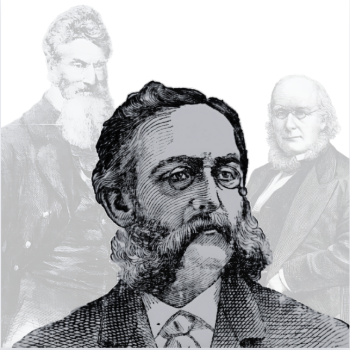

Colonel Henry Steel Olcott (pronounced all-caught by the natives and all-talk by the Europeans) left the Theosophical Headquarters in Adyar on August 4, 1888. After a two-day journey by train, he was now approaching the new Victoria Terminus in Bombay.[1] He would have celebrated his fifty-sixth birthday two days before he left, but as he was still recovering from an illness, it was more reflection than festivity. The recent letters from William Quan Judge and Blavatsky, his partners in the triumvirate of Theosophical Founders, did little to improve his spirits.

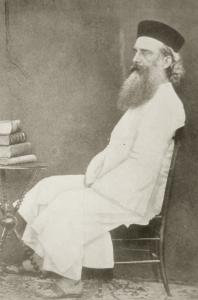

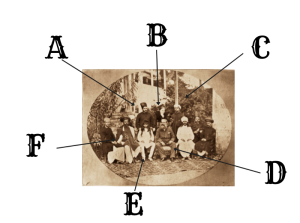

Col. H.S. Olcott.

He was irritated, a fact betrayed by an ocular quirk (that was only somewhat concealed by his spectacles.) One of his eyes was “extremely disobedient,” and would, on occasion, meander off on its own (sometimes with most disagreeably.) So long as his “disobedient eye” remained stationary, everything was calm, but when irritated, and something twitched, the rogue eye strayed knavishly, and the confidence of his face diminished.[2] As for his other characteristics, Olcott wore his white locks and beard long, and this contrasted sharply to the ruddy bronze tan he developed after a decade in India. His stature was not very tall, nor particularly commanding. He had a sturdy frame more suggestive of a practical administrator than the striking power of an apostle or seer, and in truth, Olcott claimed to be neither. It was his sympathy for the mysticism and spiritual thought of the East, and his ability to appreciate a life “full of great fluid possibilities and splendid potencies hidden under the surface,” however, that led Olcott to a life devoted to a religious revival of India. It was a characteristic of the best side of American genius; the same affinity with Eastern philosophy that elevated the work of Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman, to the transcendental dreams.

Though he was President of the Theosophical Society, he received almost all of his ideals and inspiration for his work from Blavatsky, the frenetic genius who needed a man with just such a nature to supplement her more potent character. Like Moses, Blavatsky was the “seer and law-giver,” while Olcott managed the practical details of overseeing a growing international semi-religion. While they were together, between 1879 and 1884, it was the enthusiastic eloquence of Olcott that succeeded in creating the unprecedented movement for the revival of Eastern learning, having 4,000 pledged adherents in India and Ceylon, of all religions, castes, and creeds. When Blavatsky left India, however, Olcott’s enthusiasm was checked, and his “apostolic energies” greatly restricted. He turned his attention to more practical schemes, like the collection of old Indian manuscripts; the administration of culinary schools for Indian servants; the editing of the journal The Theosophist; the improvement of his home at Adyar, and other matters of like nature.[3]

With this tacit understanding of their respective roles, Olcott could be forgiven for his irritation at being roped into the “Paris imbroglio” which sprang from a disturbance in the Isis Branch. After the death of Louis Dramard (the founder of the Isis Branch) the work in Paris was administered by a young man taken up as a protégé by Blavatsky named F.K. Gaboriau. Though he was enthusiastic about Theosophy, Gaboriau demonstrated little in the way of executive faculty. He tried his best to shepherd the Isis Branch to stability, and even spent most of his recently inherited modest patrimony on Theosophical publications, but as is often the case in the wake of a leader’s death, Gaboriau became involved in disputes of succession. Blavatsky, in her capacity as Co-Founder (and assumed capacity as Olcott’s representative) had taken Gaboriau’s side in the matter and granted Gaboriau a charter of a sweeping and unprecedented character, allowing him to do practically as he pleased. This made a bad mess for Olcott, and he protested Blavatsky’s cavalier overreach. Blavatsky suspected that Olcott would not like it very much to have the “whole machinery of the Society upset to gratify her whim,” wrote a letter to Olcott, remembering, of course, that the more she threatened him the more stubborn he became. It said:

Now look here, Olcott. It is very painful, most painful, for me to have to put to you what the French call marché en main, and to have you choose. You will say again that you “hate threats,” and these will only make you more stubborn. But this is no threat at all, but a fait accompli. It remains with you to either ratify it or to go against it and declare war to me and my Esotericists. If, recognizing the utmost necessity of the step, you submit to the inexorable evolution of things, nothing will be changed. Adyar and Europe will remain allies, and, to all appearance, the latter will seem to be subject to the former. If you do not ratify it—well, then there will be two Theosophical Societies, the old Indian and the new European, entirely independent of each other. I write in all calmness and after full deliberation, your having granted the Charter to […] having only precipitated matters!

Olcott, and others at Adyar, though loyal, were growing concerned over Blavatsky’s recent actions. The Theosophists in London were divided. Some remained in Sinnett’s London Lodge, while the majority joined her new section, “The Blavatsky Lodge,” of which Blavatsky herself was named “President.” She had taken a commodious house in London with a signboard ready to pave painted on it either “European Headquarters of the Theosophical Society” or “Western Theosophical Society.” The “stand-and-deliver ultimatum” of her recent letter had frightened the Hindu members of the Theosophical Society’s Executive Council, who were alarmed for the stability of the movement in the West. At the entreaty of the Council, a Paris arbitration was organized with Olcott being dispatched to Europe as mediator.[4]

The conflict in America was more difficult to mediate. The problem there, like France, was one of authority. Dr. Elliott Coues, President of the Gnostic Branch (Washington, D.C.) was “working hard for the notoriety he craved.” William Q. Judge, General Secretary of the American Section and President of the Aryan Branch (New York) was opposing him. Olcott was aware that Judge’s brother, Fred, recently died in Calcutta from cirrhosis of the liver. As such, Olcott adjusted his sympathy to the occasion. [5] Throughout June (and right up until he left Adyar) Olcott received a stream of letters from Judge updating him on the situation with Coues.[6] To add to this conflict, T. Subba Row, a valued member of the Society, resigned just weeks earlier.[7] It was a deflating summer.

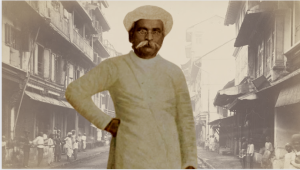

Tukaram Tatya.

“Colonel Olcott!” said a man with a deep, intense, voice that so perfectly answered the fire of his eyes. He wore all white, and a turban too small for his head. “Welcome back to Bombay.”

“Tukaram!” said Olcott warmly, embracing his old friend. “Bhavani! Rustomji!” said Olcott, acknowledging Tukaram’s companions. “It is certainly good to see you gentlemen.”

(Far Left) Rustumji, (Center Right) Olcott, (Far Right) Bhavani.[8]

Tukaram was a Hindu, of the Bhandari caste and, as the leathered wrinkles of his face indicated, was close to the soil.[9] His little green umbrella, or chhatra, was the only accoutrement to suggest a man of note. It was said that in ancient times, some king or another adopted the symbol of the umbrella as a mark of distinction. Other high-ranking officials embraced the emblem, and the presence of large, decorated umbrellas became synonymous with nobility. In time, the title of “Chhatrapati,” or “Lord of the Umbrella,” became more coveted by Mahratta Princes than even raja (king,) or maharaja (great-king.)[10] Bhavani Shankar was a young Brahman from the north. Like Tukaram, he was an early associate of the Founders. He regarded Blavatsky as a “grand woman,” and had several encounters with the Masters. An accomplished Sanskritist, Bhavani, like so many Brahmans, knew all his sacred books by heart.[11] Rustumji Ardeshir Master, a Parsi, was the Secretary of Bombay Branch.[12] He was the overseer of the Manockjee Petit Mill, one of the cotton-mills of fellow Parsi, Sir Dinshaw Petit.[13]

“During the previous year the Bombay Branch held sixty meetings where lectures on various topics were delivered,” said Rustumji.[14]

Olcott looked in marvel at the city he once called home. It had certainly changed.

The Secretariat, the University, the Town Hall, an array of other new buildings in the “Indo-Gothic” style now dominated the city.[15] The Victoria Terminus, completed just three months earlier, was conspicuous from every open space in Bombay.[16]

Victoria Terminus.

“Progress,” said Tukaram.

“Mr. Tukaram?” said Rustomji.

“Progress,” Tukaram repeated, pointing his umbrella toward the huge statue which crowned the dome of Victoria Terminus. “It is a statue of the Goddess of Progress,” he said solemnly. “Men are born, live out their brief life and die. Nations rise, reach a certain height, and fall. Civilizations are built up, shaped and polished only to decay each in turn and be succeeded by new systems evolved by new races of men. In the now all-powerful civilization of Europe, hastening so rapidly to its zenith, there is one element lacking that held a foremost place in mightier systems now all but forgotten. The element of man’s higher nature in evolutionary development. The practical knowledge of the soul.”[17]

“I just received a letter from Professor Müller,” said Olcott. “He writes to say that he pleased that you are publishing the Krishna Yajur Yeda Sanhita,” said Olcott, fishing for the letter from his bag. “Here,” he said, showing the letter to Tukaram. “Professor Müller says, and I quote:

It would have been mere waste to print a new edition of the Rig Veda with Sayana’s commentary. The second edition of this work which, with the generous assistance of His Highness the Maharajah of Vizianagaram, I am now printing at the University Press, and which will contain many corrections of the old edition, will answer all wants in Europe and India for some time to come. Then there is still so much to be done in publishing really correct editions of important Sanskrit texts. To print the same text twice would have been woeful extravagance. But it seems to me, considering the higher object of the Theosophical Society, that you ought to publish a complete and correct edition of the Upanishads. There is a collection of the Upanishads, published at Madras in Telugu letters, which might serve as a model. The Upanishads are after all the most important portion of the Vedas for philosophical purposes, and if the Theosophical Society means to do any real good, it must take its stand on the Upanishads, and on nothing else. I am thinking of publishing a cheap edition of my English translation of the Upanishads, but I must wait till the first edition published in the Sacred Books of the East is quite sold out.[18]

“Hmm,” said Tukaram, nodding his head buoyantly left and right. “I also received a note from Professor Müller. He advised me to give up the printing of the Rig Veda, but I am unable to take up to his advice. The work has been put in the printer’s hands, and much expense incurred on account of it. The first Ashtak is nearly ready for sale.”[19]

~

Tukaram was a skilled merchant, and successful, operating the business firm of Messrs. S. Narayan & Co. He possessed a great dream in his heart, however, which flamed over the sordid matters of his trade. Born in Bombay, Tukaram’s father died early in his youth. He was then adopted by his brother’s wife. By the time he reached adulthood, Tukaram was interested in the issues of social inequality in India. While working on the railways of the Walcot Company, he developed close connections with the circle of lower-caste radicals in Poona, including the anti-caste social reformer, Jotirao Phule.[20] In 1861, writing under the name “Ek Hindu” (‘One Hindu’ or ‘A Hindu,’) Tukaram published a revolutionary work titled Jalibheil Viveksar (A Critique of Caste Divisions.) Published by Vasudev Babaji Navrange (one of the founders of the Prarthana Samaj,) Jalibheil Viveksar was the first work written in Marathi to critique the religious hierarchies of Hinduism from the perspective of a lower-caste adherent. In this work Tukaram argued that Brahmins operated a monopoly over learning and authority, and suggested that social divisions should, instead, be based on the merit of each individual. Tukaram claimed that no conventional Kshatriya Varna existed in a pure form, nor any varna for that matter, as they had all been mixed with each other. In 1865 Tukaram’s friend, Jotirao Phule, published a second edition of Jalibheil Viveksar.[21] In the preface of that edition, Phule writes: “the book described how in the name of religion, Brahmins shielded their self-interest, their selfishness, and their narrowness; how they walked off and divided Hindu life into narrow and isolated little grooves.”[22] Jalibheil Viveksar would influence Phule’s own works, Priestcraft Exposed (1869) and Slavery (1873,) and lay the conceptual foundation for the anti-caste movement.[23] Phule, for example, would repurpose the Marathi term, Dalit (“crushed”/”broken,”) to describe the “untouchables” born outside of caste.[24] In 1874, the year in which Olcott met Blavatsky, the Satyashodhak Samaj (Truth Seekers Society, a well-known anti-caste collective of lower-caste activists in a village near Pune,) distributed free copies of Jatibhed Viveksar and used the text as an ideological resource for its activism.[25]

Olcott and the Bombay Theosophists passed the Esplanade, with its bhandaris, palm-groves, and tamarind trees that provided the many sylvan inspirations for street names in the city.[26] 17 Tamarind Lane was the site of the Bombay Theosophical Publication Fund, and where Tukaram Tatya lived.[27] Olcott looked at the stacks of books and copy. In some ways, August 6, 1888, marked the fourteenth anniversary of the beginnings of the Theosophical Society. It was the summer of 1874 when Olcott met Blavatsky at the haunted farm of the Eddy brothers in Vermont. Olcott was writing a piece for a New York newspaper.[28]

“Before leaving New York City,” said Olcott, “I thought it well to ascertain the views of the Head Centre of modern Spiritualism as to these objective phenomena. I found Andrew Jackson Davis in his cozy bookstore, at 21 East Fourth street.”[29]

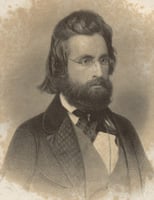

Andrew Jackson Davis.

Davis was the father of American Spiritualism, who introduced the concept of the “Laws of Attraction.” His works were greatly influenced by his predecessors, Emanuel Swedenborg, and Franz Mesmer. The notion of a natural energy, or “magnetic fluid,” which transferred through all matter (animate and inanimate alike) was articulated in Mesmer’s theory of “animal magnetism.” The idea that manipulating such currents of living energy was known as Mesmerism.[30] Olcott was not only a believer in Mesmeric healing, but he was also a practitioner. Olcott taught Tukaram “the art of mesmeric healing” and had Tukaram developed into a homeopathic practitioner of repute.[31]

“I arrived in Rutland on the 28th of August,” Olcott explained. “My reception was in the highest degree unsatisfactory. I did not like the people or the attention they showed me, which was such as they would be likely to give an ordinary dog. They refused to admit me at first, but I clung to them with such pertinacity that they finally made room for me.”[32]

Olcott and Blavatsky were joined at Eddy Farm by the Spiritualist, Dr. James M. Peebles, who had just returned to America from Ceylon where he witnessed a great debate between Buddhist orators and Christian Missionaries known as the “Panaduraa Waadaya.”[33] Blavatsky and Peebles were already somewhat acquainted with one another. When Blavatsky lived in Cairo, Egypt, in the early 1870s, she operated a Spiritualist Society known as the Société Spirite. When Dr. Peebles last toured Asia, he paid a visit to Cairo where he called on Blavatsky at her rooms in the Oriental Hotel.[34]

Dr. James Martin Peebles.

In 1878 Dr. Peebles was giving a lecture series in the environs of the New York metropolis. While in town, he visited the Theosophists at the Lamasery. Peebles had just returned from India and Ceylon. On a whim, Olcott showed Peebles a photograph in his possession of two Hindu men he met during his travels in 1870. Olcott then asked Peebles if he met either of the men during his trip. By one of the incredible “coincidences” that life sometimes provides, Peebles had indeed met one of them, the named Thackersey Mooljie. Peebles, it just so happened, was carrying Thackersey’s address in his pocket. Olcott wrote to Thackersey and told him about the Theosophical Society, and the plan to relocate to Ceylon. Thackersey joined the Society, and told the Theosophists of the Arya Samaj, “a strong Movement in India for spiritual purification and resuscitation of the Vedic teachings,” headed by a great Sanskrit pundit and reformer named Swami Dayanand Saraswati. Thackersey subsequently introduced Olcott to Hurrychund Chintamon, the President of the Bombay Branch of the Arya Samaj. As the weeks passed, there was an exchange of letters, books, opinions between Olcott and Hurrychund. Olcott then sent a letter to Saraswati pledging the support of the Theosophists and requested assistance on matters of Hindu spirituality.[35] Hurrychund, realizing that the aims and principles of the Theosophical Society and the Arya Samaj were in sympathy, suggested that the two groups should be amalgamated as one to increase the power and usefulness of both.[36]

Dayanand Saraswati.

Thackersey then acted as intermediary between the Theosophical Society and Tukaram’s friends, the Poona reformers, and by the middle of the summer of 1878, some of the most notable activists had joined the Theosophical Society.[37] These names included Rao Bahadur Gopal Hari Deshmukh, Shankar Pandurang Pandit (poet and playwright,) Anna Moreshvar Kunte (author of a commentary on the Hindu system of medicine,) Shyamji Krishna Varma (Indian lawyer who founded “India House,” and produced an English translation of the rules of the Arya Samaj,) and Mahadev Moreshwar Kunte (author of The Vicissitudes of Aryan Civilization in India.)[38],[39] The caliber of conversation “among the cultured class” of Poona, according to Olcott, was comparable to that of a “German or English University town.”[40] Perhaps the most widely-recognized member of the Poona Theosophists to join at this time was Mahadev Govind Ranade, Justice of the Bombay High Court, and a man whom Olcott considered one of the “noblest men of Modern India,” whose “name was respected throughout the whole country by all alike—Europeans and Indians.”[41] Contact with these men inspired Olcott and Blavatsky to relocate the headquarters of the Theosophical Society to India instead of in Ceylon (as was their original plan.)[42]

The practical effects of Saraswati’s assistance were soon made known in America. Days before leaving for India, on November 21, 1878, Blavatsky, Olcott, Judge, and other Theosophists, performed the first cremation funerary service on American soil.[43] The sacred text which they used was Saraswati’s own Veda Bhashya (Veda Commentary.)[44] Though the Veda Bhashya was criticized by orthodox brahmins and orthodox scholars (like Max Müller,) Saraswati’s teachings (initially at least) were championed by the Theosophists. David A. Curtis, an early New York Theosophist and reporter for The New York Sun, did much to popularize Saraswati in popular media. In an article titled “The Martin Luther of India” for Frank Leslie’s Sunday Magazine Curtis writes:

One who shall accomplish what [Saraswati] has undertaken will be worthy of being accounted great, even by those who may lament that he rejects Christianity. Preaching the pure theism of the Vedas, he is gradually destroying what the missionaries of Christ have always declared to be the greatest foe to their progress, namely the superstition of idolatry. If he is not sowing the seed, he is at least breaking up ground that has lain not for centuries, but for thousands of years. Shall we dare to say that his reward will be less than theirs work with a full knowledge of Christianity?[45]

Olcott and Blavatsky arrived in Bombay in 1879 and secured a building at 108 Girgaum Back Road. It was in Bombay where they first published their journal, The Theosophist.[46]

108 Girgaum Road.[47]

In the beginning the funds for the Bombay Lodge were very meagre. Luckily, they were able to find better lodgings in a bungalow in the neighborhood of Breach Candy called the “Crow’s Nest.” It had a fine panoramic view of the Mahalakshmi Temple but having been “discredited by a reputation for snakes and ghosts,” the bungalow remained vacant for some time.[48]

Mahalakshmi Temple, Breach Candy by Francis Firth.

Though Tukaram’s interests ran parallel to the objectives of Theosophical Society, he was skeptical of the Theosophists, and scrutinized their intentions from afar. He doubted that Europeans would “give up their home interests merely for the sake of learning Eastern philosophy,” and believed that “there must be some humbug at the bottom of the affair.”[49] Tukaram resolved see for himself “what sort of folk [the Theosophists really were.” Impressed with the actions of Blavatsky and Olcott, Tukaram joined the Society in May 1880.[50] From the moment of his joining, Tukaram supported the Society in every way. His business firm, Messrs. S. Narayan & Co., became the first banker of the Bombay Lodge.[51]

Putting his literary talents to use, Tukaram wrote The Yoga Philosophy: Being the Text of Patanjali, with Bhoja Raja’s Commentary in 1882. It was the first complete edition of Patanjali’s Yoga Philosophy. Tukaram states in the preface:

Patanjali’s work on the philosophy of Yoga, having been written in Sanskrit, is inaccessible to the general public who are not conversant with that learned language. With a view to meet this want, the work was some time ago translated into English partly by the late Dr Ballantyne and partly by Govind Shastri Deva. But these translations have not been compiled together, and consequently the whole work is not easily accessible. Their reprint, therefore, in one complete volume, has become necessary at the present day when interest has been revived in the study of the Yoga philosophy throughout India by the Theosophical Society […] The Edition now offered to the public is calculated to counteract the materialistic tendencies of the present age and to re-open the path of the true spiritual philosophy and science of the ancient Aryans. It is hoped that it will be acceptable to the religious and philosophic world, especially to those profound thinkers who are engaged in the solution of the great problem of human life and that it will lead to a proper understanding of the Infinite in a true and scientific sense.[52]

The book was a massive success and sold out within four months of publication.[53]

108 Girgaum Road.[54] (A.) T. Harachand. (B.) Blavatsky (C.) Tukaram (D.) Olcott

(E.) Damodar Mavlankar (F.) Bal Nilaji Pitale.[55]

“How is the Dispensary?” asked Olcott.

“We now treat over 90 people a day?” Tukaram replied.[56]

In 1884 Tukaram opened the Bombay Homoeopathic Charitable Dispensary.[57] It was a part of the growing trend of clinics and sanitoriums which promoted homoeopathic and naturopathic remedies. The newest being Dr. Heinrich Lahmann’s Sanitorium in Dresden, Germany.[58] These resorts and facilities had grown in popularity in both Europe and India. In Darjeeling, Eden Sanitarium (est. 1882) catered to Europeans while the Lowis Jubilee Sanatorium (est. 1887) catered to the natives.[59] It was not a coincidence that these health resorts (and countless others like them) sprang up in the 1880s. The world looked very different, especially the cities. In urban domestic migration and ethnic immigration crowded the streets. Electric lights, for the first time in history, weakened the wall of night. Streetcars, billboards, foreign sounds, loud fragrances, and an endless cacophony of newness drowned all senses without a chance to breathe. As Blavatsky would write:

In scenery, the picturesque and the natural is daily replaced by the grotesque and the artificial. Scarce a landscape in England but the fair body of nature is desecrated by the advertisements of “Pears’ Soap” and “Beecham’s Pills.” The pure air of the country is polluted with smoke, the smells of greasy railway-engines, and the sickening odors of gin, whiskey, and beer. And once that every natural spot in the surrounding scenery is gone, and the eye of the painter finds but the artificial and hideous products of modern speculation to rest upon, artistic taste will have to follow suit and disappear along with them.[60]

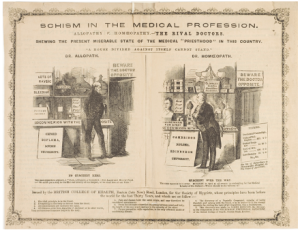

“Schism in the Medical Profession: Showing the Present Miserable State of the Medical ‘Priesthood’ in This Country.”[61]

The new multiplicity of identities, unplanned and haphazardly integrated, produced an urban organism with “multiple personalities.” In came the reformers and self-appointed medical experts who used their authority in public health to define disease and enact state measures for social control. Naturally, there were those who believed in the right to self-determination regarding their physical fate and saw such measures as an affront to their autonomy, way of life, and traditions. (It was, after all, within this milieu that the idea of “human improvement” gained traction. In 1883 Francis Galton, a cousin of Charles Darwin, coined the term “eugenics” to describe “the study of agencies under social control that may improve or impair the racial qualities of future generations either physically or mentally.”) Movements such as allopathy and homeopathy, “physical culture,” and vegetarianism arose as a “back to nature” response to yet another industrial encroachment.[62]

~

Tukaram met W.Q. Judge, of New York’s Aryan Theosophical Society, not long after he established the Bombay Homoeopathic Charitable Dispensary.[63] This connection would be the first steps in a Theosophical Indo-American literary partnership. Theosophy was becoming more widely known, and to capitalize on the general public’s interest in ancient Indian texts (and counteract the propaganda of Christian missionaries) Tukaram established Bombay’s Theosophical Publishing Fund. Through this, he published works on Indian philosophy, metaphysics, the Vedas, and the Upanishads (with English translations, and Indian vernacular.)[64] Tukaram was also in the beginning stages of establishing the Bombay Theosophical Publishing House at the same time “the idea took shape in New York,” with Judge’s Aryan Press.[65] Within a year Tukaram would publish a Second Edition of The Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali. This edition was widely circulated among Theosophists in all parts of the world.[66]

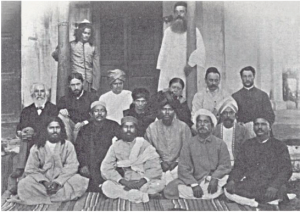

“Group of delegates to Convention of 1884.”[67]

As the activities of the Bombay Lodge grew, they were compelled to rent a room for the first time. In February 1886 meetings began to be held on Rampart Row.[68] That same time Govindarao Sattay (while working for the cause of Indian freedom in America) arranged for shipment of Sanskrit books to be shipped from Bombay to America and be distributed among the public libraries of Washington, D.C., New York, and Boston.[69]

1888 was a busy year in Tukaram’s publishing department. That year saw the release of his A Compendium of the Raja Yoga Philosophy, in which he expressed hopes of expounding Shankaracharya’s theory of the Higher Self “before aspirants to spiritual knowledge,” of both the East and the West.[70] Not long before Olcott arrived, in the summer of 1888, Tukaram, sent the entire consignment of The Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali (and a large number of the Wilkins Edition of Bhagavad Gita) to America care of W. Q. Judge.[71] In this cultural exchange, Tukaram would circulate over 3,000 copies of The Epitome of Theosophy in India. [72] Epitome would also be republished the in the newspapers, Subodh Patrika, and Indian Spectator.[73] Tukaram also published Subba Row’s lectures on the Bhagavad Gita under the title Discourses on the Bhagavad Gita.[74] Copies of this work were forwarded to Max Müller, but the Professor “did not think it worthwhile to acknowledge even the receipt of the pamphlet.” “In all probability,” it was reasoned, “the fact that it came from a Theosophist was the reason of this.”[75] Tukaram did, however, receive a note from Müller advising him “to give up the printing of the Rig Veda with Bashya,” and focus on the Upanishads.[76] Tukaram declined this advice, and would publish both the Rig Veda with Bashya, and The Twelve Principal Upanishads (the latter being the first Devanagari edition of the 108 known Upanishads using notes from the commentaries of Sankaracharya.)[77]

~

“The Shannon.”

After spending the day with the Bombay Theosophists, Olcott boarded the P. & O. Steamer, the H.M.S. Shannon for Brindisi on August 7, 1888.[78]

Not long after boarding, Olcott came across a long-haired, bare-foot, Englishman, who wore a light-colored turban and scarlet jersey bearing the name of the Salvation Army.[79] He was a familiar face to the people of India. It was Frederick Tucker-Booth, otherwise known as “Commissioner Tucker.” As was the custom of the Salvation Army, the first part of his hyphenated surname came from his wife, Emma Booth, the daughter of General Booth (co-founder of the Salvation Army.) Commissioner Tucker married Emma in April of that year in a ceremony at Congress Hall, in Clapton in England.[80]

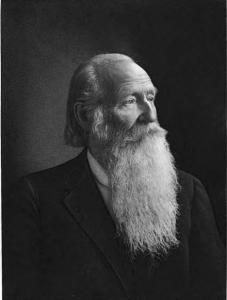

Commissioner Frederick Booth-Tucker.

A few years earlier Commissioner Tucker was Judge Tucker of the Supreme Court of India, a position with a yearly salary of several thousands of pounds. He lived in fine official style, with scores of servants, and was in the front of line for a big government promotion. Judge Tucker, however, was a religious man, and the “spiritual state of the millions of Hindus troubled him greatly.” He was convinced that they could “never be reached by ordinary means.” While in this state of contemplation, he was given a copy of War Cry, the official organ of the Salvation Army, and developed an interest in the story it told of the “marvelous conquest won by the soldiers of the cross, who wore the uniform of the Salvation Army.” He went to England to talk to General Booth and offered his services to movement. Judge Tucker resigned his office in the government and proceeded to the Salvation Army training school. He remained there until General Booth sent him back to India in 1882, this time a Salvation Army officer.[81]

Olcott may have differed on the finer point of theology with Commissioner Tucker, but their spiritual ethos was harmonious. In any case, both men belonged to that small club of hirsute, western, men who wore the robes and turbans of the east; if their libraries did not look the same, their closets certainly did. A conversation was easily struck-up.

“During my return journey from India, I visited Count Cesare Mattei in Italy,” said Commissioner Tucker. “I was so favorably impressed by the Count’s exposition of the ‘Mattei System’ that I came away believing almost as much in Count Mattei as I had previously learned to believe in the Mattei medicines.”

Commissioner Tucker then showed a demonstration by applying one of Mattei’s “electricities” as a lotion to the hand of a man which had been crushed in some machinery. Olcott was impressed, for he thought such a treatment may be of use to Tukaram’s clinic.

“The Salvation Army in India has followed a path differing from that of other workers in this vast Mission Field,” said Commissioner Tucker. “There has been no desire whatever in doing so to reflect on the plans, or policies, pursued by others; but we have believed that our own path was the most direct.”

Commissioner Tucker was faithful to General Booth’s mission when he returned to India, but the dignity of his former position chafed him. He became convinced that he should “give up all for the sake of the perishing souls around him.” One day he left his house and took up his quarters in one of the poorest of the mud huts among the natives. Then he replaced his Western clothes with the saffron garments of a mendicant, and taking the brass begging vessels of a pauper, he went forth to meet the natives, now as “Fakir Singh,” the “Lion of God.”[82]

“When we came to India,” said Commissioner Tucker, “we put our Salvation clock half an hour faster than the other religious clocks in India by adopting native dress. This was not fast enough to suit us, and so we soon put on another half-hour by adopting the fakir costume. This was still too slow, so we put on another half-hour by going barefooted. Too slow still, so we went in for Indian food. Not fast enough yet, so we started begging and living under trees, and then began to twist the hands of our clock to see if we couldn’t get another half-hour extra. English shirts were next discarded, and nothing but a light cloth kept for the shoulders. If we can find any fresh way of adding another half-hour, we are determined to do it. People may say, ‘How ridiculous and extravagant to have our clocks three hours faster than everybody else’s.’ Some would like us to keep Church of England time, and others Methodist or Baptist time, but we take our quadrants and have a good look at the Sun of Righteousness, so as to find out the correct time which is kept by the clocks of Heaven. No differences up there—all the clocks agree with the great ‘ Thy-will-be-done ‘ clock-tower. Only the earthly clocks are a long way behind. We are getting ours regulated and are only sorry it has taken so long.”[83]

The Salvation Army and the Young Men’s Christian Association belonged to a Christian movement known as “Muscular Christianity,” or “Christian manliness,” that endeavored to energize the churches to counteract the devitalizing effects of urban living. (The term bodybuilding was first coined in 1881 by Y.M.C.A. physical culturist, Robert J. Roberts.) To realize such aims, they promoted competitive sports and physical education.[84] The zeal of the Salvation Army extended into other areas of “leisure.” Focusing on the urban underclass, followers would preach against the ills of pub culture and prostitution with military discipline. In the 1880s they supported W.T. Stead in his mission against child prostitution, and to support the match-girls in the East End, they opened their own match-factory with better working conditions.[85]

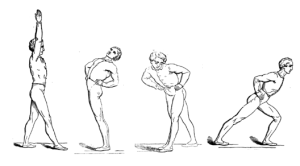

The self-conscious European interest in the development of the body as a measure of regenerating both the moral and physical fiber of their respective nations began, unsurprisingly, with the advent of race theory and urbanization in the early nineteenth century. Each country developed their own gymnastic program and output of instructional books regarding “man- making” exercises. Donald Walker’s British Manly Exercises (1834) included the new sports of sailing, riding, and rowing, for example. The doctrine of “a sound mind and a sound body,” like other ideological fads imposed on the working class by their “concerned” superiors, the movement quickly welcomed itself into all facets of British society. During the 1830s reformation of English public schools, the movement saw to it that to more games and sports along the lines of military training were included in the curriculum. This meant that it was the calisthenic regiment developed by the Swede Pehr Henrik Ling (father of the Swedish Massage.) Nurtured within the English schools, Muscular Christianity, was well on its way to “moulding the perfect English[wo]man.” At the time that Tukaram published the Patanjali’s Yoga Philosophy, the girls’ department of the London School Board introduced Ling’s exercises at the suggestion of Mathias Roth. By 1888, 40,000 girls in the London Board Schools were trained in Ling’s free exercises. In the preface to the 1887 edition of Gymnastic Exercises, Roth states:

Ling’s Exercises may be introduced with the greatest advantage into every school and seminary; in fact, they should constitute a part of sound and good education. A healthy body is the best condition for the development of a healthy mind. Itis hoped that parents, and all those who are engaged in the noble profession of tuition, will give their earnest attention and their practical support to the enlightened system of Ling. It need not be said that these exercises are also very useful for preparing the recruit or volunteer for his military training.[86]

Illustrations from Roth’s Gymnastic Exercises Without Apparatus.[87]

It was not long before proponents of Muscular Christianity used it as a standard for the moral and physical superiority of a nation, religion, and empire, and as a means to negatively contrast the subjugated peoples of lands whose peoples did not share the same bodies and beliefs.

Individuals, like the nations and empires they belonged to, came to believe that by improving their individual body, they were improving the collective racial body to which they belonged.

Illustrations from F.J. Harvey’s Physical Exercises and Gymnastics for Girls and Women.[88]

The eugenic compulsion stemmed from what was believed to be an imbalance of “body-mind-soul.” An imbalance, it was said, that developed from intellectual over-development at the expense of the spiritual and physical atrophy. As such, within the genetic makeup of physical culture there was a noticeable marker of anti-intellectualism. Or put another way, physical and spiritual fitness was seen as a holistic measure to restore the ecosystem of “mind-body-spirit.”

Annie Payson Call.

The September 1888 issue of the American Theosophical journal, The Path, would publish something of a foreshadowing. In an article titled “Theosophical Aspects of Contemporary Literature and Thought,” attention was called to an article in The New Jerusalem Magazine by Annie Payson Call titled “The Regeneration of the Body.”[89] The article in question stated:

It is a well-known fact that a locomotive engine utilizes only nineteen percent of the fuel it burns, the other eighty-one percent is, so far as we can see, matter absolutely wasted. So, it is with the use of the human body in its present state, and especially with the American human body.[90]

The Path stated that Call had discovered in her studies of the Delsarte System “that that system has for its basis the same facts of physical training that underlie the Yoga philosophy.” [91] The article in The Path continued by stating:

A gentleman interested in occult researches, and who has spent much time in the Orient on meeting Miss Call and witnessing illustrations of the system which she exemplifies, declared that the motions were identical with those of Buddhist temple girls in Japan. Miss Call’s ideas agree not only with the Eastern Philosophy but correspond with the teachings of Through the Gates of Gold and of Kernning, the German adept. The former tells us that we must act with Nature and use the animal in the service of the Divine part of our being, when a profound peace will fall upon the palace; and the latter says that we seem to use the mind, but the mind in reality uses us. There has gone up a great and earnest cry among seekers for enlightenment here in the West for something practical; Miss Call is one of those who offer it to us in the shape of the beginnings, at least of a method of “Yoga practice” simple and effective, without the strains and dangers involved in the Hatha-Yog, but quite adapted to our Western nature. We trust that enough disciples may be gained for this admirable adaptation of the Delsarte system to apply and introduce it so generally as to meet the demands of Western students of Occultism. [92]

To get an idea of what Call had in mind, one need only turn to her 1891 work, Power Through Repose, in which she states:

The first care should be to gain quiet, as through repose of mind and body we cultivate the power to “erase all previous impressions.” In class, quiet, rhythmic breathing, with closed eyes, is most helpful for a beginning. The eyes must be closed and opened slowly and gently, not snapped together or apart; and fifty breaths, a little longer than they would naturally be, are enough to quiet a class. The breaths must be counted, to keep the mind from wandering, and the faces must be watched very carefully, for the expression often shows anything but quiet. For this reason, it is necessary, in initiating a class, to begin with simple relaxing motions; later these motions will follow the breathing. Then follow exercises for directing the muscles. The force is directed into one arm with the rest of the body free, and so in various simple exercises the power of directing the will only to the muscles needed is cultivated.[93]

In New York W.Q. Judge was working on an “Americanized” version of Tukaram’s work on Patanjali which he would publish in 1889 under the title The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali. “Instead of being a translation,” Judge would write, “it is offered as an interpretation, as the thought of Patanjali clothed in [English.]”[94] While the marriage of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras and the exercises of physical culture were well underway in the West, a concurrent phenomenon was happening in the East. The schools of India, based on the English model, also received its share “physical culture” based on Ling’s system. In fact, Ling’s gymnastic exercises, widespread in Indian schools, would influence the postures of emergent hatha yoga.[95] In the coming decades Western “physical culture” of Muscular Christianity would shape the native exercise revival that would produce postural yoga. In the refiner’s fire of India, what began as physio-spiritual exercises imposed by foreign power, were transmuted into a symbol of superior strength and will, and an absolute rebuttal of Western narratives of Indian degeneracy. Like the Victoria Terminus, the architecture of yoga would become an Indo-Gothic spirituality.

Patanjali’s Yoga Aphorisms (1889.)

~

On August 22, two weeks out to sea, the Shannon was a day away from Brindisi. Olcott sulked the deck of ship while chewing on his displeasure with Blavatsky and the tensions in the Paris Branch. When he returned to his cabin, a letter from the Masters materialized in the air and fell on his desk.[96] Olcott read its contents:

To Henry Olcott

Again, as you approach London, I have a word or two to say to you. Your impressibility is so changeful that I must not wholly depend upon it at this critical time. Of course, you know that things were so brought to a focus as to necessitate the present journey and that the inspiration to make it came to you and to permit it to the Councilors from without. Put all needed restraint upon your feelings, so that you may do the right thing in this Western imbroglio. Watch your first impressions. The mistakes you make spring from failure to do this. Let neither your personal predilections, affections, suspicions nor antipathies affect your action.

Misunderstandings have grown up between Fellows both in London and Paris, which imperil the interests of the movement. You will be told that the chief originator of most, if not of all these disturbances is H. P. B. This is not so; though her presence in England has, of course, a share in them. But the largest share rests with others, whose serene unconsciousness of their own defects is very marked and much to be blamed. One of the most valuable effects of Upasika’s [Blavatsky’s] mission is that it drives men to self-study and destroys in them blind servility for persons. Observe your own case, for example. But your revolt, good friend, against her infallibility—as you once thought it—has gone too far and you have been unjust to her, for which I am sorry to say, you will have to suffer hereafter along with others. JUST NOW, ON DECK, your thoughts about her were dark and sinful, and so I find the moment a fitting one to put you on your guard.

Try to remove such misconceptions as you will find, by kind persuasion and an appeal to the feelings of loyalty to the Cause of truth if not to us. Make all these men feel that we have no favorites, nor affections for persons, but only for their good acts and humanity as a whole. But we employ agents—the best available. Of these for the past thirty years the chief has been the personality known as H. P. B. to the world (but otherwise to us.) Imperfect and very troublesome, no doubt, she proves to some, nevertheless, there is no likelihood of our finding a better one for years to come—and your theosophists should be made to understand it. Since 1885 I have not written, nor caused to be written save thro’ her agency, direct or remote, a letter or line to anybody in Europe or America, nor communicated orally with, or thro’ any third party. Theosophists should learn it. You will understand later the significance of this declaration so keep it in mind. Her fidelity to our work being constant, and her sufferings having come upon her thro’ it, neither I nor either of my Brother associates will desert or supplant her. As I once before remarked, ingratitude is not among our vices.

With yourself our relations are direct and have been with the rare exceptions you know of, like the present, on the psychical plane, and so will continue through force of circumstances. That they are so rare—is your own fault as I told you in my last. To help you in your present perplexity: H. P. B. has next to no concern with administrative details, and should be kept clear of them, so far as her strong nature can be controlled. But this you must tell to all:—With occult matters she has everything to do. We have not abandoned her; she is not “given over to chelas.” She is our direct agent. I warn you against permitting your suspicions and resentment against “her many follies” to bias your intuitive loyalty to her. In the adjustment of this European business, you will have two things to consider—the external and administrative, and the internal and psychical. Keep the former under your control and that of your most prudent associates, jointly; leave the latter to her. You are left to devise the practical details with your usual ingenuity. Only be careful, I say, to discriminate when some emergent interference of hers in practical affairs is referred to you on appeal, between that which is merely exoteric in origin and effects, and that which beginning on the practical tends to beget consequences on the spiritual plane. As to the former you are the best judge, as to the latter, she.

I have also noted, your thoughts about The Secret Doctrine. Be assured that what she has not annotated from scientific and other works, we have given or suggested to her. Every mistake or erroneous notion, corrected and explained by her from the works of other theosophists was corrected by me, or under my instruction. It is a more valuable work than its predecessor, an epitome of occult truths that will make it a source of information and instruction for the earnest student for long years to come.

Srinivasa Row is in great mental distress once more because of my long silence, not having a clear intuition developed (as how should he after the life he has led?). He fears he is abandoned, whereas he has not been lost sight of for one moment. From day to day, he is making his own record at the ‘Ashram,’ from night to night receiving instructions fitted to his spiritual capabilities. He has made occasional mistakes, e.g., once recently, in helping thrust out of the Headquarters house, one who deserved a more charitable treatment, whose fault was the result of ignorance and psychical feebleness rather than of sin, and who was a strong man’s victim. Report to him, when you return, the lesson taught you by [symbol] at Bombay and tell my devoted though mistaken “son” that it was most theosophical to give her protection, most un-theosophical and selfish to drive her away.

I wish you to assure others [Tukaram Tatya,] [Rustomji Adeshir Master,] [Norendro Nath Sen,] N.D.C., [G.N. Chakravarti,] U.U.B., T.V.C., P.V.S., N.B.C., C.S., C.W.L., [Dina Nath Ganguly,] D.H., S.N.C., etc. among the rest, not forgetting the other true workers in Asia, that the stream of karma is ever flowing on, and we as well as they must win our way towards Liberation. There have been sore trials in the past, others await you in the future. May the faith and courage which have supported you hitherto endure to the end. You had better not mention for the present this letter to anyone—not even to H.P.B. unless she speaks to you of it herself. Time enough

You had better not mention for the present this letter to anyone—not even to H.P.B. unless she speaks to you of it herself. Time enough when you see occasion arise. It is merely given you, as a warning and a guide; to others, as a warning only, for you may use it discreetly if needs be.

—K.H.[97]

The Shannon Letters.

← →

THE AGONISED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS:

INTRO: CHARLEY.

I. WITCH TALES.

II. CARELESS WHENCE COMES YOUR GOLD.

III. THE TIMES ARE CHANGED.

IV. DENIZEN OF ETERNITY.

V. DOMOVOY.

VI. WITH LOW AND NEVER LIFTED HEAD.

VII. IMPERIAL GOTHIC.

VIII. THE SERVANT OF THE QUEEN.

IX. THE DWELLER ON THE THRESHOLD.

X. INDO-GOTHIC YOGA.

XI. INTENDED FROM ABOVE.

XII. THE SÉANCE ON CHEYNE ROW.

XIII. EVEN IN NEW ROOMS.

XIV. RUSSIA’S LEGENDARY LORE.

[APPENDICES]

SOURCES:

[1] “Colonel Olcott’s Lectures.” The Madras Weekly Mail. (Madras, India) September 26, 1883; “The President’s Tour.” Supplement to The Theosophist. Vol. IX. No. 108. (September 1888): 9.

[2] Sergeyevich Solovyov, Vsevolod. A Modern Priestess of Isis. Longmans, Green, And Co. London, England. (1895): 36-37.

[3] Johnston, Charles. “Colonel Olcott At Home.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. VI., No. 10. (February 1901): 182-188.

[4] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume IV. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1910): 55-58.

[5] “Death of Mr. Fred C. Judge.” Supplement to The Theosophist. Vol. IX. No. 106. (July 1888): xivi.

[6] Judge’s letter from June 8, 1888, said: “Certain matters are occurring here which need attention and action. [Dr. Coues’] policy is to place himself at the head of some wonderful unknown thing through which (save the mark!) communications are alleged to come from the Masters. He also, in a large sense, wishes to pull the Theosophical Society away from your jurisdiction and make himself the Grand Mogul of it in this country. I know that ⸫’s policy is to retain complete control in you, and my desire is to keep the American Section as a dependency of the General Council in India; hence you are the President. (⸫ is the Symbol of Master Morya.) It was never my intention to dissever, but to bind, and the form of our Constitution clearly shows that. That’s why no President is elected or permitted here. So, I would recommend that you call the Council and consider our Constitution, which ought long ago to have been done—and decide that we are in affiliation and subordination to India, and that we are recognized as part of the General Council, with power to have a Secretary as an (official) channel, but not to have a yearly President, but only a chairman at each Convention. I cannot work this thing here properly without your co-operation.” [Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume IV. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1910): 49-50.] On July 24, Judge added: “I am glad you are at last going to take some proper notice of the Convention. If notice had been taken before of U. S. affairs it would perhaps have been better. There is no doubt that American T. S. affairs are looking up; and I—perhaps alone—regard the U. S. as the center of the movement, for I believe that it is here the next race will appear. It is significant that the T. S. was started here. India is necessary to it (as I said in The Path) and it to India. But India cannot claim to be it all. Indeed, it is getting to be secondary I think, even if the Adepts still reside there. I am fully in accord with you as to the importance of the [Adyar] Library and all the rest, but I want to suggest that the T. S. if it is what it claims, a thing of ⸫’s creation, it cannot remain where it was when it was started or where it got to in 1884. It must press on, and it must change or—it must die. Hence a change is expected in its 14th year which is heralded and felt to begin in its 13th. This is the 13th year, and this will witness a change. I do not know if you are ready to meet it. It has seemed to me that you have of late got a fondness for forms; and I have always thought that you gave away your power to Boards and committees too much. Your idea that the T. S. must be put into such a shape that it might live on after your death is based upon the assumption that you are the only man who could carry it on and that at your death it would die unless its rules and constitution were fixed. This I do not concur in. If you died, some others would be provided. The T. S. is getting stuck, and it has to be got out of the rut. Of course, these are only my opinions. I telegraphed you about Coues. All the same, as I have for two years kept you well-informed about him, it seemed as if you could have decided yourself. Besides, such an act would be against your own forms.” [Judge, William Quan, and A. L. Conger. Practical Occultism. Theosophical University Press. Pasadena, California. (1951.) (Letter: William Q. Judge to H.S. Olcott, Bombay, India, July 24, 1888.)

[7] “Resignations.” The Supplement to The Theosophist. Vol. IX. (June 1888): xlii; Row, T. Subba. The Philosophy of the Bhagavad-Gita: Four Lectures Delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, Held in Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 by T. Subba Row: An Appreciation. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras, India. (1921): v-xix. [T. Subba Row: An Appreciation by S. Subramaniem.]

[8] “An Imported Religion.” The Sun. (New York, New York) April 13, 1890.

[9] Johnston, Charles. “A Vision of Things to Come.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 112, No. 6. (December 1913): 830-836.

[10] Birdwood, George C.M. The Industrial Arts of India. Pt. II. Chapman And Hall, Limited. London, England (1884): 241; “The Umbrella: Its History.” Arthur’s Home Magazine. Vol. LIV., No. 4. (April 1896): 249-251.

[11] Johnston, Charles. “A Vision of Things to come.” The Atlantic Monthly Vol. 112, No. 6. (December 1913): 830-836; Finch, Laura I. “H.P. Blavatsky and Phenomena.” The Occult Review. Vol. XLV, No. 6 (June 1927): 404-405.

[12] “Officers, Council and Branches of The Theosophical Society.” Supplement To The Theosophist. Vol. IX. (January 1888): li-lxvii.

[13] Johnston, Charles. “Colonel Olcott At Home” The Theosophical Forum Vol. VI., No. 10. (February 1901): 182-188; Johnston, Charles. “A Vision of Things to come.” The Atlantic Monthly Vol. 112, No. 6. (December 1913): 830-836.

[14] “General Report Of The Thirteenth Convention Of The Theosophical Society At The Headquarters, Adyar, Madras, December The 27th, 28th, and 29th, 1888.”

[15] Arnold, Edwin. India Revisited. Trübner & Co. London, England. (1886): 54-55.

[16] “The New Great Indian Peninsular Railway Victoria Terminal Building, Bombay.” Scientific American. Vol. XXVI, No. 677. (December 22, 1888): 10,815-10,816; Caine, William Sproston. Picturesque India: A Handbook for European Travellers. George Routledge And Sons Limited. London, England. (1891): 6.

[17] Tatya, Tukaram. A Guide to Theosophy. Theosophical Publication Fund. Bombay, India. (1887): i.

[18] Müller’s letter in full: “Though I wrote to you yesterday only, I write once more to tell you and your friend Tookaram Tatya that I am pleased to see from the Indian Spectator of July 1st that the Krishna Yajur Yeda Sanhita has been undertaken by the Theosophical Publication Fund, instead of the Rig Veda. This text will be useful, and I shall be glad to subscribe to it. You might go on with publishing the Taittiriya Brahmana; likewise, the White Yajurveda, Samaveda, and Atharva Veda, both Sanhita and Brahmana, text and commentary. It would have been mere waste to print a new edition of the Rig Veda with Sayana’s commentary. The second edition of this work which, with the generous assistance of His Highness the Maharajah of Vizianagaram, I am now printing at the University Press, and which will contain many corrections of the old edition, will answer all wants in Europe and India for some time to come. Then there is still so much to be done in publishing really correct editions of important Sanskrit texts. To print the same text twice would have been woeful extravagance. But it seems to me, considering the higher object of the Theosophical Society, that you ought to publish a complete and correct edition of the Upanishads. There is a collection of the Upanishads, published at Madras in Telugu letters, which might serve as a model. The Upanishads are after all the most important portion of the Vedas for philosophical purposes, and if the Theosophical Society means to do any real good, it must take its stand on the Upanishads, and on nothing else. I am thinking of publishing a cheap edition of my English translation of the Upanishads, but I must wait till the first edition published in the Sacred Books of the East is quite sold out. If you have sufficient funds, you should also print the commentaries on the Upanishads, but you should take care that the edition is entrusted to competent hands, so that we should get a critical edition, based on a careful collation of the best manuscript like our best editions in Europe. At present the issue of a beautiful and correct edition of the text seems to me almost a duty to be performed by the Theosophical Society. Please to urge this very strongly on your friend and tell him from me that I always find the Grantham manuscripts the most correct and most useful.” [Müller, F. Max. “The Theosophical Society’s Publication Fund.” The Theosophist. Vol. X, No. 111. (December 1888): 143.]

[19] Tatya, Tookaram. “Publication Work.” The Theosophist. Vol. X. No. 112. (January 1889): 254.

[20] Keer, Dhananjay. Mahatma Jotirao Phooley: Father of Indian Social Revolution. Popular Prakashan. Bombay, India. (2002): 93-95; O’Hanlon, Rosalind. Caste, Conflict, And Ideology: Mahatma Jotirao Phule and Low-Caste Protest in Nineteenth-Century Western India. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, England (1985): 42-45.

[21] O’Hanlon, Rosalind. Caste, Conflict, And Ideology: Mahatma Jotirao Phule and Low-Caste Protest in Nineteenth-Century Western India. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, England (1985): 42-45.

[22] Keer, Dhananjay. Mahatma Jotirao Phooley: Father of Indian Social Revolution. Popular Prakashan. Bombay, India. (2002): 93-95.

[23] Jaywant, Ketaki. “Reshaping the Figure of the Shudra: Tukaram Padwal’s Jatibhed Viveksar (Reflections on the Institution of Caste.)” Modern Asian Studies. Vol. LVII. (2023): 380–408.

[24] Pandey, Gyanendra. A History of Prejudice: Race, Caste, And Difference in India and The United States. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, England. (2013): 6.

[25] Jaywant, Ketaki. “Reshaping the Figure of the Shudra: Tukaram Padwal’s Jatibhed Viveksar (Reflections on the Institution of Caste.)” Modern Asian Studies. Vol. LVII. (2023): 380–408.

[26] Edwardes, Stephen Meredyth. The Rise Of Bombay: A Retrospect. Times of India Press. Bombay, India. (1902): 37.

[27] Tatya, Tukaram. “Publication Work.” The Theosophist. Vol. X. No. 112. (January 1890): 254.

[28] Olcott, Henry S. People From The Other World. American Publishing Company. Hartford, Connecticut. (1875): 32.

[29] Olcott, Henry S. “The World of Spirits.” The Sun. (New York, New York) September 5, 1874.

[30] Davis writes: “Each human spirit possesses within itself an eternal affinity of parts and powers; which affinity there exists nothing sufficiently superior, in power and attraction, to disturb, disorganize, and annihilate. These are evidences with which the world is not familiar; but they are plain and demonstrative; and are destined to cause great happiness and elevation among men.” Davis, Andrew Jackson. The Great Harmonia. Vol. I. (Fourth Edition.) Sanborn, Carter, & Bazin. Boston, Massachusetts. (1855): 189.

[31] “Charitable Dispensary in Bombay.” Supplement to the Theosophist. Vol. I., No. 10. (October 1884): 143.

[32] “Col. Olcott’s Lecture.” The Rutland Daily Globe. (Rutland, Vermont) December 7, 1874.

[33] Peebles, James Martin. Buddhism and Christianity: Being an Oral Debate Held at Panadura. P.K.W. Siriwardhana. Colombo, Ceylon. (1953): i-ii.

[34] Peebles writes. The Angel of Spiritualism has sounded the resurrection trumpet of a future existence in every land under heaven. Madame Blavatsky, assisted by other brave souls, formed a society of Spiritualists in Cairo about three years since. They have fine writing-mediums, and other forms of the manifestations. They hold weekly séances during the winter months. Madame Blavatsky is at present in Odessa, Russia. The lady, whose husband keeps the Oriental Hotel, is a firm Spiritualist. Fired with the missionary spirit, I left a package of pamphlets and tracts in her possession, for gratuitous distribution. ‘And, as ye go, teach,’ was the ancient command.” Peebles, J.M. Round The World; Or Travels in Polynesia, China, India, Arabia, Egypt, Syria, And Other “Heathen” Countries. Colby And Rich, Publishers. Boston, Massachusetts. (1875): 315.

[35] On May 21, 1878, Olcott writes: “Venerated Teacher, A number of American and other students, who earnestly seek after spiritual knowledge, place themselves at your feet and pray you to enlighten them. The boldness of their conduct naturally drew upon them public attention and reprobation of all influential organs and persons whose worldly interests or private prejudices were linked with the established order. We have been called atheists, infidels, and pagans. We need the assistance not only of the young and enthusiastic, but also of the wise and venerated. For this reason, we come to your feet as children to a parent to say, “look at us your teacher. Tell us what we ought to do; give us your counsel and your aid,” See that we approach you not in pride, but humility; that we are prepared to receive your counsel and do our duty as it may be shown us.” [“The Theosophists Assailed.” The Sun. (New York, New York) May 31, 1882.]

[36] “Home Notes.” The Evening Journal (Vineland, New Jersey) November 9, 1878; Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume I. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1895): 395-396; Murphy, Howard. Yankee Beacon Of Buddhist Light: Life of Col. Henry S. Olcott. Theosophical Publishing Society. Wheaton, Illinois (1988): 95-96.

[37] Olcott, Henry Steel. “In Memory of Mr. Ranade.” Supplement to The Theosophist. Vol. XXVI. (September 1905): i.

[38] Shyamji Krishna Varma’s “India House,” which operated from 1905 to 1910 at Cromwell Avenue in Highgate, London, was a residence for Indian youths pursuing higher education in England. The building developed into a prominent overseas hub for political activism and revolutionary Indian nationalism. In 1908 Myron Phelps, a Manhattan lawyer and Theosophist in the Theosophical Society of which Johnston was affiliated, established The Society for the Advancement of India. That same year he would open a sister “India House” in New York at 1142 Park Avenue. Two other members of the New York-based Theosophical Society, Lizzie Chapin, and Maud Ralston would become involved in this project, and establish another branch of The Society for the Advancement of India in Detroit, Michigan. Through this connection, Ralston would meet and marry an Indian immigrant named Thakar Dev Sharman; in later years she would compose the poem “The Charkha,” which was a popular “song of freedom” for the Indian Independence Movement. Maude and Thakar Dev Sharman would later become involved with the Sri Aurobindo Ashram. [Curtis, David A. “The Martin Luther of India.” Frank Leslie’s Sunday Magazine. Vol. IV, No. 6. (December 1878): 657-661; “Useless to Rebel Now.” The Calgary Herald. (Calgary, Alberta, Canada) July 4, 1908; “Converts Are Not Genuine.” The Detroit Free Press. (Detroit, Michigan) August 16, 1908; Ganachari, Arvind Gururao. “Myron H. Phelps (1856-1916): An Early American Advocate of India’s Freedom.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Vol. LII (1991): 650-657; Ghose, Sri Aurobindo. “To Mr. and Mrs. Sharman (c. January 1926.).” Sri Aurobindo. Autobiographical Notes and Other Writings of Historical Interest. Accessed May 25, 2021. https://aurobindo.site/workings/sa/37_36/0286_e.htm; Prabhu, R.H. Song of Freedom. Popular Frakashan. Bombay, India. (1967): 63-64; Ralston, Maude. “The India Society of Detroit.” The Modern Review. Vol. X (September 1911): 234-237; Sasson, Diane. Yearning for the New Age, Laura Holloway-Langford and Late Victorian Spirituality. Indiana University Press. Bloomington, Indiana. (2012): 265-266; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 6293. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Lizzie Chapin; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 6294. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Maude Ralston. Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 6042. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Myron H. Phelps.

[39] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 156. (Website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Rao Bahadur Gopal Hari Deshmukh. (7/7/78); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 157. (Website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Shankar Pandurang Pandit. (7/7/78); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 158. (Website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Anna Moreshvar Kunte. (7/7/78); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 159. (Website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Shyamaji Crishnavarna [Shyamji Krishna Varma.] (7/7/78); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 161. (Website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Mahadev Moreshwar Kunte. (7/31/78.)

[40] “The Theosophists at Poonah.” The Civil & Military Gazette. (Lahore, Pakistan) October 27, 1883.

[41] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 160. (Website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Mahadev Govind Ranade. (7/31/78.)

[42] Olcott, Henry Steel. “In Memory of Mr. Ranade.” Supplement to The Theosophist. Vol. XXVI. (September 1905): i.

[43] Blavatsky writes: “Evening: Held the Vedic ceremony of casting the Baron de Palm’s ashes into the sea. A highly interesting episode. Our mysterious Hindoo Brother […] was present with his helper […] H.S.O. cast the ashes into the waters of N. Y. Bay at exactly 7:45 p.m. November 21.” [Curtis, David A. “The Last of Baron De Palm.” The Sun. (New York, New York) November 21, 1878; Blavatsky, H.P. H. P. Blavatsky Collected Writings: Vol. I (1874-1878.) Theosophical Publishing House. Wheaton, Illinois. (1966): 421.]

[44] The chant was as follows: “Do thou, O soul, by the grace of God and by thy own merits, depart by the best paths to the best regions. Oh! Being, may thy eyes be assimilated to the sun. May thy soul go to the wind. Do thou depart by the merit to the glory of the sun, or be happy on earth, or go to the region of the clouds, or re-enter life where thou wilt be happy. Do thou live contented in the vegetable world, and having entered blessed human life, do thou attain the highest good. Oh, being, do thou glorify thou valor and greatness, May the light of thy mind, glorify thee and thy body. Oh blessed and God, bless this being, and take him to the regions of the blessed. Oh being, may thy body, created by the grace of God, be happy and beneficent. The funeral fire is Kravyada. We walk that fire to the distance. May it reach the regions of the wind midway between heaven and earth. That fire is rapid in light. May it take thee quickly to the blessed regions. May other sacrificial fires and the grace of God ever shine in our midst, and bless the learned. Oh, being, do thou depart to the blessed regions. Do thou enjoy perpetual air, the firmament, the blessed body, the equally blessed knowledge, and communion with God; and having enjoyed long life and the comforts thereof, do thou again thyself from the body and enter another blessed life. We pray to God, our common father and protector, that He may bless us perpetually. Oh being, may God, the preserver of us all, and the regulator of our lives according to our own ways of living, and the liberator from death or life, accept us, his suppliant creatures, and liberate us from all evils. Oh, God, who are free from all evils, do thou liberate this being and ourselves from evil. Oh Indra, the Lord of Lords, do thou again bless this mortal being and ourselves with the blessed senses and the government of the earth, do whereby we may enjoy the earth in a better life. Oh, Lord, do thou preserve this being, bless him with good qualities, and make him bold to do good deeds, and bless us also. Do Thou engage this being, as well as ourselves, in good and pious deeds. Oh, exalted God! Bless our people and take this being to the celestial regions and make him happy. Lord, do Thou make this being happy in future life. May this funeral ceremony prove a blessing to this being. May the regions of the sky, dark at night, fair in the days and ruddy in the morning and evening, be a source of blessing to this being. May the Creator of the world, the Supreme Being, bless this being with a good life. Oh being, thy mind, traversed the regions of the wind and light of the sun, has traveled far. We pray to God that thou mays’t be able to re-enter life and enjoy it in a better manner and position. May thy mind grasp the light of the sun, the earth, the land, and the four directions, the sea, the rays of the sun, water and vegetable kingdom, the dawn the moving universe the stars and planets, theist, and future times, and if thou desire anything beyond this, may thy mind be liberated from desire by the grace of God, and do thou enjoy happiness by being born again among us or in better life.” Curtis, William E. “Baron De Palm’s Ashes.” The Sun (New York, New York) October 20, 1878.

[45] Curtis, David A. “The Martin Luther of India.” Frank Leslie’s Sunday Magazine. Vol. IV, No. 6. (December 1878): 657-661.

[46] Dhammapala, Bhikku Devamitta. “Reminiscences of My Early Life.” The Maha Bodhi Centenary Volume 1891-1991. [Vol. XCVIII, Nos. 7-12 (1990) & Vol. XCIX. Nos. 1-12 (1991.)]: 66-71.

[47] Wadia, K. J. B. Fifty Years of Theosophy in Bombay. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, India (1931): 3.

[48] Sinnett, A.P. Incidents in the Life of Madame Blavatsky. George Redway. London, England. (1886): 236-237; Wadia, K. J. B. Fifty Years of Theosophy in Bombay. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, India (1931): 3, 9-10.

[49] Olcott, Henry Steel. “Tookaram Tatya.” The Theosophist. Vol. XIX, No. 10 (July 1898): 627-628.

[50] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume II. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1900): 149-150; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 292. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Tookaram Tatya. (5/1/80.)]

[51] Wadia, K. J. B. Fifty Years of Theosophy in Bombay. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, India (1931): 9-10.

[52] Tatya, Tukaram. The Yoga Philosophy: Being the Text of Patanjali, with Bhoja Raja’s Commentary. Bombay Branch of the Theosophical Society. Bombay, India. (1882): Preface.

[53] Tatya, Tukaram. The Yoga Philosophy: Being the Text of Patanjali, with Bhoja Raja’s Commentary. (Second Edition.) Subodha-Prakash Press. Bombay, India. (1885): Preface.

[54] Wadia, K. J. B. Fifty Years of Theosophy in Bombay. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, India (1931): 38.

[55] “An Imported Religion.” The Sun. (New York, New York) April 13, 1890.

[56] Olcott, Henry S. “The President-Founder’s Address.” General Report Of The Thirteenth Convention Of The Theosophical Society. (1889): 2-13.

[57] “Charitable Dispensary in Bombay.” Supplement to the Theosophist. Vol. I., No. 10. (October 1884): 143.

[58] Hau, Micael. “Asceticism And Pleasure in German Health Reform: Patients as Clients in Wilhelmine Sanatoria.” Essay in Beyond Pleasure: Cultures of Modern Asceticism, edited by Evert Peeters, Leen Van Molle, and Kaat Wils. Berghahn Books. New York, New York. (2011): 42-61.

[59] Bhattacharya, Nandini, ‘The Sanatorium of Darjeeling: European Health in a Tropical Enclave’, Contagion and Enclaves: Tropical Medicine in Colonial India (Liverpool, 2012; online edition. Liverpool Scholarship Online. June 20, 2013. https://doi.org/10.5949/UPO9781846317835.002.

[60] Blavatsky, H.P. “Civilization, The Death of Art and Beauty.” Lucifer. Vol. VIII, No. 45 (May 15, 1891): 177-186.

[61] Homeopathy Ephemera. n.d. <a href=”https://wellcomecollection.org/”>Wellcome Collection</a>. https://jstor.org/stable/community.24756930.

[62] Cayleff, Susan E. Nature’s Path: A History of Naturopathic Healing in America. Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. 1-11.

[63] Joshee, G.V. “Some Account of Burmah.” The Mahratta. (Poona, India) July 13, 1884.

[64] Judge, W.Q. “Faces of Friends: Tookeram Tatya.” The Path. Vol. IX, No. 2 (May 1894): 36-40.

[65] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. IV, No. 9. (December 1889): 290-294.

[66] Tatya. Tukaram. The Yoga Philosophy, Being the Text of Patanjali, With Bhoja Raja’s Commentary. [Second Edition: Revised, Edited and Reprinted for the Bombay Theosophical Publication Fund.] Printed at the Subodha-Prakash Press. Bombay, India. (1885): Preface; Judge, William Q. The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali. The Path. New York, New York. (1889): v.

[67] (Top) Bhavaji, Colonel Olcott (Upper Middle) Major-General Morgan, W. T. Brown, T. Subba Rao, Madame Blavatsky, Franz Hartmann, R. Gebhard. (Bottom Middle) Narendranath Sen, Damodar Mavalankar, Ramaswamiyer, Srinavas Rao. (Bottom) Bhavani Rao, T. V. Charlu, Tukaram Tatya, V. Cooperswami Iyer.

[68] Wadia, K. J. B. Fifty Years of Theosophy in Bombay. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, India (1931): 9-10.

[69] Dall, Caroline Healey. “A Hindoo Theosophist.” Unitarian Review. Vol. XXXI, No.5. (May 1889) 397-410.

[70] Tatya, Tukaram. A Compendium of The Raja Yoga Philosophy. Bombay Theosophical Publication Fund. Bombay, India. (1888): Preface.

[71] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III., No. 7. (October 1888): 235-236.

[72] The Epitome of Theosophy was a Theosophical Tract that was prepared by the New York Theosophists to be a “comprehensive and fundamental,” explanation of Theosophical doctrines written in the vernacular. “A Theosophical Tract.” The Path. Vol. II., No. 10. (January 1888): 310-324; Keightley, Julia. (Jasper Niemand). Letters That Have Helped Me. The United Lodge of Theosophists. Los Angeles, California. (1920): 23-24.

[73] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III., No. 7. (October 1888): 235-236; “Bombay Publication Work.” Supplement To The Theosophist. (March 1889): 11.

[74] “Bombay.” Supplement To The Theosophist. (October 1888): xx; Olcott, Henry Steel. “Reviews: Lectures on The Bhagavad Gita.” The Theosophist. Vol. X, No. 110. (November 1888): 132.

[75] Row, T. Subba. The Philosophy of the Bhagavad-Gita: Four Lectures Delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, Held in Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 by T. Subba Row: An Appreciation. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras, India. (1921): v-xix. [T. Subba Row: An Appreciation by S. Subramaniem.]

[76] Tatya, Tookaram. “Publication Work.” The Theosophist. Vol. X. No. 112. (January 1889): 254.

[77] Tatya, Tukaram. The Twelve Principal Upanishads. Bombay Theosophical Publication Fund. Bombay, India. (1891); “Literary Gossip.” The Athenaeum. No. 3,296. (December 27, 1890): 891-892; Vidyatilaka. The Brahmopanisat-Sara Sangraha. Sudhindra Natha Vasu. Allahabad, India. (1916): iii.

[78] “Homeward Mail.” The Civil & Military Gazette. (Lahore, British India) August 13, 1888; Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume IV. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1910): 65-67.

[79] “Salvation Army Meeting at Torquay.” The Western Morning News. (Plymouth, England) May 11, 1888.

[80] “Salvation Army Wedding.” The Morning Post. (London, England) April 11, 1888.

[81] “The Tambourine in India.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) November 2, 1888; “Foreign Missions of the Salvation Army.” The Missionary Review of the World. Vol. XXXV, No. 11. (November 1912): 849-852.

[82] “The Tambourine in India.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) November 2, 1888.

[83] Booth-Tucker, Frederick. Muktifauj: Or Forty Years with the Salvation Army in India and Ceylon. Marshall Brothers, Ltd. London, England. (1900): xiii, 74.

[84] Clifford, Putney. Muscular Christianity: Manhood and Sports in Protestant America, 1880-1920. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. (2001): 1.

[85] Preston, William C. “’Darkest England’ Matches.” The Sunday Magazine. Vol. XXI, No. 32. (1892) 447-453; Van der Veer, Peter. Imperial Encounters: Religion and Modernity in India and Britain. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. (2001): 89.

[86] Roth, Mathias. Gymnastic Exercises Without Apparatus, According to Ling’s System. [Seventh Edition.] A.N. Myers & Co. London, England. (1887): 1-7

[87] Roth, Mathias. Gymnastic Exercises Without Apparatus, According to Ling’s System. [Seventh Edition.] A.N. Myers & Co. London, England. (1887): 1-7

[88] Harvey, Frederick James. Physical Exercises and Gymnastics for Girls and Women. Longmans, Green, and Co. London, England. (1896.)

[89] S.B. “Theosophical Aspects of Contemporary Literature and Thought.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 6 (September 1888): 195-200.

[90] Call, Annie Payson. “The Regeneration of the Body.” The Kindergarten. Vol. II, No. 12 (April 1890): 361-364.

[91] S.B. “Theosophical Aspects of Contemporary Literature and Thought.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 6 (September 1888): 195-200.