THE SÉANCE ON CHEYNE ROW

XII.

⸻

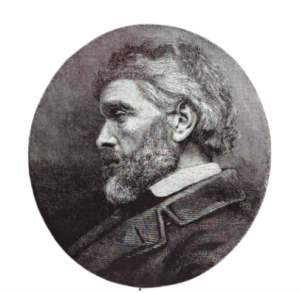

The masons were busy at No. 24 Cheyne Row, and ladders were up in front of the house when W.T. Stead and his companion from the Pall Mall Gazette turned in from the Embankment. It seemed as if the familiar old house, rendered sacred by its association with Thomas Carlyle, was undergoing a restoration. The address had certainly changed, it used to be No. 5 Cheyne Row.[1]

Cheyne Row.[2]

Upon closer examination, however, Stead found that the men with the ladders outside were only arranging to insert a medallion bust of Carlyle on the front of the house. This was to mark it out for the pilgrims who came to Chelsea from all over the Anglophone world. After standing empty for some many years, the house was once again occupied. Curtains were hung in the windows, and there were signs of life and activity far greater than those which were visible during the waning years of Carlyle’s life.

The house was now in the possession of Carlyle’s former neighbor, the fifty-eight-year-old Spiritualist, Elizabeth Ann Cottell, who purchased the property soon after the writer’s death.[3]

Her guest was the “original prophetess of the spiritual faith,” the “famous American medium,” Catherine Jencken, better known to fame as Katie Fox. When Katie was just a child in Rochester, New York, she, together with her sister, Margaret, first manifested the phenomena commonly known as “spirit rapping.” Katie had been a month in London but had yet given any public exposition of her extraordinary powers.

Katie Fox & the Carlyle House.[4]

There was something bizarre in the idea of a medium being located in Carlyle’s old house. It was with mixed feelings that Stead rang at the door. It was Madame Novikova who introduced Stead to Carlyle, just after they, themselves, had met. She introduced him to James Froude, William Gladstone, and a host of other notable men during that romantic time. It was nine years earlier, in 1879, when Stead last stood at this spot. Carlyle had bidden Stead a kindly farewell as he left him on his own doorstep following a pleasant drive over Haverstock Hill.[5]

Carlyle Smoking Under the Awning in the Garden.[6]

On entering the house, it was evident that although the outer framework was there, the whole interior had been changed. The garden behind in which Carlyle used to smoke still remained as it was in the days when the rooster’s clarion woke the fretful philosopher in his eyrie on the roof. (Carlyle built a windowless room on top of the house.)[7] Carlyle’s austere living room, however, gave place to the luxurious furnishing of the well-to-do “old lady of cats and emeralds.”[8]

They went upstairs to the three-windowed-room where Stead first made Carlyle’s acquaintance, and where Carlyle breathed his last breath. The room, which in Carlyle’s time contained little furniture beyond a chair, a couch, and a couple of tables, was full of the elaborate nick-nacks of a modern drawing-room. A large oil painting of the Duke of Wellington hung on the wall fronting the windows, and the bookcase that stood at the side of the fireplace, had disappeared.

Stead did not even recognize it as the same room as the one he last stepped foot in on that sunny November morning in 1879.

Stead glanced at the ivory statue of Buddha.

“It’s from India,” said Cottell. “My late husband, Major Cottell, and I resided there for some time.”[9]

(Left) Portrait Screen in Garrett Gallery. (Right) Fireplace, North Wall.[10]

“Did you know Mr. Carlyle, Mrs. Cottell?”

“Oh, yes,” she replied. “Mr. Carlyle was irascible, but he was pleasant enough to talk to, and often engaged in quietly neighborly chats with me. He had a horror of street organs and street musicians generally, and he invariably purchased their silence with money. If the coin did not secure a cessation of the music, he would threaten them with the police. To see him throw open the window and scowl at the peripatetic music grinders while throwing them their dole is a sight to be remembered.”

Katie Fox was a lady of pleasant appearance, and at fifty-one, bore little trace of the tumultuous life through which she has passed, living in constant communication with spirits of the unseen world. Her peculiar gifts, whatever they were, had been the subject of close scrutiny by the scientist, William Crookes. These gifts were not necessarily advantageous. When Katie was just a child, she and her sister, Maggie, were hurried away, concealed in a great wagon, from their home in Rochester, New York. The Fox family were in danger of being attacked by frightened mobs, stirred to action by the superstitious rabble that spoke of the “table rappings” in horror. The home of the Fox Sisters in Rochester still remained, the place where Spiritualists claimed, “the first manifestations of the new revelation were given to the world,” and over the door was an inscription which read: “In this place Spiritualism first took its rise.” Katie Fox was a widow now, and was on a visit to England accompanied by her two sons.

“Stead?!”

Stead turned around to find Edmund Russell. He was having his portrait painted by an artist who used Carlyle’s rooftop-eyrie as a studio. He stopped on to dinner, and decided to stay for the séance.[11]

Stead expressed his natural surprise to Russell at the incongruity of holding a séance in Carlyle’s old room.

“Oh,” said Cottell, “I do not feel that Mr. Carlyle has ever left it. He is constantly moving about the room—you can hear him at times! On one occasion he was materialized before us, and I heard once more the familiar voice which I had so often heard in the old time when we were next-door neighbors. It is but natural that he should cling to the old place. There are strange creakings and knockings, as if someone was moving behind the furniture and the pictures, and these noises always remind me of his presence, and, indeed, we receive many communications from him.”

Materializations only occurred in dark séance, and it was broad daylight. Katie Fox was not a materializing medium, she was a “psychographer,” a “spirit-writer.” Any communication, therefore, which they might have with the “Sage of Chelsea” had to be accomplished by writing, not viva voce.

“You may hear the rappings elsewhere in the room,” said Katie, before beginning the séance proper. “The spirits rap wherever they prefer.” Katie then politely requested the spirits to communicate their presence in the “usual way.”

In response to her request, a series of raps were heard. No one was visible, and nothing could be seen as to what could have caused the curious knocking. This, however, was just a prelude to the business that was to commence.

The participants of the séance, the “sitters,” sat about a curiously carved, round, wooden table. They did not put their hands on the table or touch it in any way. There was no invocation; there was no singing of mournful melodies that were often employed at séances as a preliminary to the apparition of the spirits. A sheet of thin foolscap was laid upon the table and a lead pencil. Katie sat facing the light. Stead was on her right. Russell, and Stead’s Pall Mall confrere to her left, and Cottell sat facing her (with her back to the window.)

“Knocks” were heard under Katie’s chair. Then the “knocks” were heard on the table itself. They were rappings like those that might be produced with a fingernail. But Katie’s hands were visible (and motionless,) and there was no visible motion on any part of her body.

“I feel like writing,” said Katie, and grasping a pencil with her left hand she began writing upon the paper In front of her.

Katie did not know what she was writing, and no human being could say what it was as she wrote. The characters could only be read when held up to a looking-glass, or through the paper from the reverse side. The sitters watched the movement of Katie’s hand intently until it finally stopped.

Thomas Carlyle.[12]

Stead took the paper and held it to the light. The name of “T. Carlyle” was appended as a signature to the message:

My friend, I rejoice to meet you. I have all that I longed for. Why do you not converse with your own loved ones, and have faith, that they may draw near enough to enter into your sphere?—T. Carlyle.

“To think of old Carlyle coming back to hang round this table!”’ Stead exclaimed.

Instantly there were knocks, and Katie Fox’s left hand began writing. When the message was held to the light, the following reproof was beheld:

Friend, be more respectful. I am no longer old; I am a young man now.

The sitters asked some more questions, and then received the following reply:

Let the departed rest. Their lives need no trumpet to sound their praise, and I feel very sorry that my poor wife was so badly treated.

“By whom?” they inquired.

No answer.

“By Mr. Froude?” Stead modestly suggested.

The response was undecided.

“By yourself?” boldly inquired one of the sitters.

Again, an undecided kind of knock left them in doubt as to whether he was lamenting remorsefully his treatment of Mrs. Carlyle, or whether he was merely wrath with some others who had treated her ill. Then came a pause. Katie Fox again clutched the pencil, and began to write:

I am here—Elizabeth.

No one present admitted that they had known any Elizabeth in the flesh.

“It is probably Queen Elizabeth,” Stead suggested.

The pencil then began to write:

I am sure you will greet me some time—Adelaide.

They were equally in the dark, but there was a suggestion of Queen Adelaide. Again, the medium’s hand was agitated, and she wrote:

Perhaps you will know me better as Queen Anne. I was Queen Anne, and many others, on the stage.

“Queen Anne has never been represented in any drama on the English stage,” Russell stoutly protested, “as she is not a person whose career lent itself to dramatization!”

“Perhaps it is Queen Anne of Denmark, or Queen Anne of Cleves,” said Cottell, extricating Kate from the situation.

Then, after some further scribblings, a message came that was signed by an eminent poetess.

You cannot forget me. Meet me for a private message.

But in response to all inquiries as to when the message was to be delivered, no answer was vouchsafed.

“All of the other sitters should be sent out of the room,” said Stead, “in order that the private message should be delivered.”

This suggestion was emphatically vetoed by the negative knock.

The “rappists,” whoever, or whatever, they were, paid close attention to the conversation of the sitters in the room, and would, on occasion, indicate a declarative assent or dissent to some statement expressed by any of the participants.

“I have frequently written in languages which I know nothing of,” said Katie, “as the movement of my hand is purely mechanical.”

Among other languages, Katie had written in Russian, and long conversations had been held in her presence in the Morse telegraphic alphabet, which she did not understand. She again grasped the pencil and began writing. This time the message was addressed to Stead:

You will be very successful, my friend. Go ahead accomplish your work. A great surprise is coming for you in a few days, and that will open the way for you to great events.—Benj.

“Who is Benjamin?” Stead asked.

Everyone present began to recall the names of any friends or relations who might have borne that name.

“I know of no Benjamin,” said Stead, “unless it is Benjamin Disraeli.”

Immediately three emphatic knocks indicated that that precise Benjamin was the control at that moment in the room.

“I should think that you would be the last man in the world whom Lord Beaconsfield (Benjamin Disraeli) would care to receive,” Stead’s confrere intimated.

“There were mysterious knockings at Hughenden Manor when I visited the place,” said Stead, “although there was no one in the house at the time.”

“Possibly that was Benjamin’s spirit,” suggested Russell.

Instantly three emphatic knocks confirmed the accuracy of the surmise.

Benjamin Disraeli.

“How odd,” said Stead. “The juxtaposition of Benjamin Disraeli and Thomas Carlyle! I remember well coming into this room when Mr. Carlyle was living. It was during the Afghan War, and I remarked that things were not looking well, when Mr. Carlyle, turning round, remarked with vehemence, ‘And they will never look any better, sir, unless it please the heavenly, or the infernal, power to take away this damnable Jew, a man who has brought more shame and disgrace upon this country than any other man in the whole course of her history.’”

A month after the fall of Plevna, Stead paid a visit to Carlyle. The writer railed against Disraeli and called on Stead to use his influence in the press to condemn Disraeli’s rumored intention to “save the Sultan.”[13]

A pause then ensued. It was suggested that the sitters should write down on a piece of paper the name of one person with whom they wished to communicate, and, folding it up, lay it on the table; then beside this piece of paper that they should write the names of half a dozen other people on similarly folded paper, and then ask Kate to state which piece of paper contained the person’s name with whose spirit they wished to communicate.

Facsimile of “Spirit-Writing” from the Brisbane Psychological Society, October 1888.[14]

Stead’s confrere did so and wrote the names of half a dozen defunct poets, fixing his mind upon Thomas Gay as the particular spirit with whom we wished to hold “sweet converse.” Katie touched different pieces of paper in turn and asked whether that was the name fixed upon. Raps were given to indicate that it was not, to the first. For the second, and the third, three raps came, indicating that the right paper had been touched. Unfortunately, when it was opened it turned out to be “Jonathan Swift,” and not “Gay,” and a second attempt succeeded no better.

Then a message came from an unnamed “poetess.”

I wish to deliver a private message to Stead. Put the paper with the pencil underneath the table and I will write it with my own hand.

The sitters obeyed the “poetesses’” instructions and initialed the paper on both sides to make sure that it was not removed, and the séance went on. Unfortunately, the poetess was not able to accomplish her benevolent desire of supplying Stead with an autograph letter, as the paper was as white when they picked it up as when they laid it down. The spirits, however, rapped out a message on the table to the effect that they had been trying to write but could not do so on account of the light.

It was then suggested that an attempt be made to produce a message by rapping by letter. Katie then said the letters of the alphabet out loud, and the spirit rapped when the right letter was reached. By this means the following message was laboriously rapped out:

I can help you in your present anticipation. You have a bright path to step in, entirely different from the present, my friend. You will not dislike the old Jew when your efforts are crowned with success.—Benj.

All efforts to ascertain what this particular path in life Stead was to take, failed.

“Now,” said Stead, “I have received a telegram that an important letter is coming for me tonight. Can the spirit tell me whom that letter is from, or what its contents are?”

This, however, was “a stumper.” At last, they were informed that Disraeli’s previous message referred to the Stead’s expected letter:

You will soon be called from London on important business.—Benj.

“I cannot leave London at present,” said Stead.

Another message:

Not until you can go with ease. You will have an offer.—Thomas Carlyle

Then another:

I am anxious to meet you again, my friend.—T. C.

Medium “Spirit-Writing” at Table.[15]

Stead’s skeptical confrere showed signs of ridiculing the performance and was told “in compassionate charity” that it was people such as he who made the most fervent believers in the end. “When their doubts finally removed, as they certainly would be, if they severed and subjected the phenomena to a severely scientific test.”

Seeing that he was such an unbeliever, Stead proposed to expel him so the spirits might have free course to develop without the “baleful influence of his scornful skepticisms.” Stead’s suggestion, however, was strongly objected by the spirits.

Katie’s hand was again agitated. A message was again received by Stead’s mysterious “poetess,” that said:

He is not to blame. He will someday believe when he has the evidence that he requires. When God’s angels lift the curtain between them and him, and he beholds the glory that surrounds them, he will believe. First, he must have faith in God; then all the rest will be easy. Meet me, dear friend, some evening soon. I will fully satisfy your mind and my private message I must give you, my friend, soon.

Then the rapping recommenced. Another message. This one for Stead’s companion. It read:

Talk with me. I love you.—Mary.

This greatly agitated Stead’s confrère.

“I have no idea who this ‘Mary’ is.”

The sitters were then promised miraculous manifestations, including the winding up of musical boxes, and a performance on the piano by disembodied forms.

“Ah,” said Cottell, “it was marvellous the other night when we had the spirit of Thomas Moore here—he accompanied himself on the piano and sang one of his own songs!”

“That must have been extraordinarily thrilling,” said Stead.

“You must come back some evening when the manifestations will be held in another room,” said Katie, “where they are much more powerful than in Mr. Carlyle’s old sitting room.”

~

The next morning, Russell paid a visit to Blavatsky at breakfast time and told her about the strange things he saw the night before.

“What like?”

“Louder than I could crash my fist on a door.”

“Oh, that was Katie Fox!”

“Madame, is there anything spiritual in such manifestations?”

“Not the slightest. Her baby made them in the cradle. She does not even know herself.”

“What were they then?”

“There are as many undiscovered forces in the human body as in external nature, but as yet we have no Edison of the body. She automatically controls or is controlled by one of these forces which the future may universally awaken and develop to some use. All possess them now in ignorance. There is nothing not common to all. As we are built on the same structure of bones and muscles, so the gamuts of thought and emotion are the same.”

“And your own phenomena?” Russell ventured.

“Of the same order though different.” Blavatsky replied simply.

“Were yours spiritual?”

“No, psychic, but on the material plane.”

Russell then questioned Blavatsky about certain strange impulses which often came over him. (To return home suddenly. To let a dozen buses, go by, then take a certain number. To cross the middle of a muddy street apparently without reason. How he was always saved in danger by a warning that sometimes arises to a scream.)

“Your astral bell of which we read so much?”

“The same category.”

“Why do you never now—?”

“I cannot—I am too old—the physical effort of concentration necessary to produce such vibration might kill me.”[16]

← →

THE AGONISED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS:

INTRO: CHARLEY.

I. WITCH TALES.

II. CARELESS WHENCE COMES YOUR GOLD.

III. THE TIMES ARE CHANGED.

IV. DENIZEN OF ETERNITY.

V. DOMOVOY.

VI. WITH LOW AND NEVER LIFTED HEAD.

VII. IMPERIAL GOTHIC.

VIII. THE SERVANT OF THE QUEEN.

IX. THE DWELLER ON THE THRESHOLD.

X. INDO-GOTHIC YOGA.

XI. INTENDED FROM ABOVE.

XII. THE SÉANCE ON CHEYNE ROW.

XIII. EVEN IN NEW ROOMS.

XIV. RUSSIA’S LEGENDARY LORE.

[APPENDICES]

SOURCES:

[1] MacDonald, Neil. “Chelsea and its Literary Associations.” Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly. Vol. XXXIII, No. 4. (April 1892): 478-480.

[2] Blunt, Reginald. The Carlyle’s Chelsea Home. George Bell and Sons. London, England. (1895): 3.

[3] Elizabeth Ann Cottell lived at 26 Cheyne Row. [The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea: Local Studies and Archives; London, England; Kensington and Chelsea Electoral Registers; Reference: RV/1889.]; Born in 1833 [Census Returns of England and Wales, 1881. Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives of the UK (TNA): Public Record Office (PRO), 1881.]; “The Haunted House In Cheyne-Row.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) September 10, 1888.

[4] Blunt, Reginald. The Carlyle’s Chelsea Home. George Bell and Sons. London, England. (1895): 8.

[5] Brown, Stewart J. W. T. Stead: Nonconformist and Newspaper Prophet. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (2019): 31-33.

[6] Blunt, Reginald. The Carlyle’s Chelsea Home. George Bell and Sons. London, England. (1895): 8.

[7] Russell, Edmund. “The Secret Doctrine: Personal Recollections Of Madame Blavatsky.” The Occult Review. Vol. XXXI, No. 6. (June 1920): 332-340.

[8] Russell, Edmund. “The Secret Doctrine: Personal Recollections Of Madame Blavatsky.” The Occult Review. Vol. XXXI, No. 6. (June 1920): 332-340.

[9] James William Cottell. [Ancestry.com. India, Select Births and Baptisms, 1786-1947 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.]

[10] Blunt, Reginald. The Carlyle’s Chelsea Home. George Bell and Sons. London, England. (1895): 62, 82.

[11] Russell, Edmund. “The Secret Doctrine: Personal Recollections Of Madame Blavatsky.” The Occult Review. Vol. XXXI, No. 6. (June 1920): 332-340.

[12] MacDonald, Neil. “Chelsea and its Literary Associations.” Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly. Vol. XXXIII, No. 4. (April 1892): 478-480.

[13] Stead called again to tell Carlyle about Disraeli’s (Lord Beaconsfield’s) rumored intention to intervene and save the Sultan. This news infuriated Carlyle, who said: “The Turk has lain there for four centuries and more without doing a single good thing for the world or for the lands he laid himself down upon. He has never been anything but a destroyer from first to last. The only good thing he ever did was to destroy the Lower Empire, They were a bad lot of men, those Greeks, not much better than the Turks, with their lawyer-like intellects, wrangling and discussing over subtleties and forms of words and forgetting their duties until the Turk came and swept them away. Since then, he has simply been a curse and a scourge to the lands he overran. And now his hour has come. It is sheer downright Bedlamism for Lord Beaconsfield or anyone else to try to save the Turk. To drag this country into arms against Russia is the damnablest course ever suggested to the English nation in the whole course of history. And to save the Turk! Sir, the Turk is on the verge of Hell and no one but God Almighty can save him now.” [Whyte, Frederic. The Life of W.T. Stead. Vol. I. Jonathan Cape Limited. London, England. (1925): 58-59.

[14] Owen, James J. Psychography. Hicks-Judd Company, San Francisco, California.(1893): 137.

[15] Owen, James J. Psychography. Hicks-Judd Company, San Francisco, California.(1893): 209.

[16] Russell, Edmund. “The Secret Doctrine: Personal Recollections Of Madame Blavatsky.” The Occult Review. Vol. XXXI, No. 6. (June 1920): 332-340.