THE ENGLISH IN INDIA PART III.

⸻

Part three of “The English in India” in Charles Johnston’s story. In the previous instalments we explored how the British East India Company assumed control of India (Part I) and the process in which the trained their administrators (Part II.) This concluding piece breaks down the administrative hierarchy of the British Raj as it would have looked when Charley was a Covenanted Civilian in India from 1888-1890.

⸻

THE CROWN.

At the top of the administrative hierarchy of the British Raj was Queen Victoria, who took the title of Empress of India in 1876..

Queen Victoria.

THE SECRETARY OF STATE.

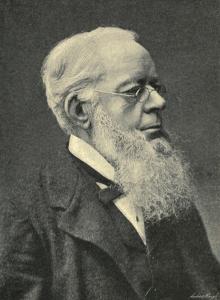

Beneath Queen Victoria/the British Crown was The Secretary of State for India, a member of British Parliament who was responsible for overseeing the political and administrative activities of colonial India. Between 1886 and 1892 the Secretary of State for India was Richard Assheton Cross.

Richard Assheton Cross. Secretary of State for India. (1886-1892)

THE GOVERNOR GENERAL/VICEROY.

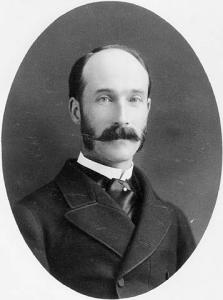

The Governor General, or Viceroy of India, was below the Secretary of State of India, and a member of the British Military. The Viceroy was responsible for executing the policy made by the Secretary of State/the British Parliament. On December 10, 1888 Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 5th Marquess of Lansdowne became the ninth Viceroy of British India (1888 and 1894.) His predecessor was Frederick Temple Blackwood, or Lord Dufferin.

The Marquess of Lansdowne. Viceroy of India. (1888-1894.)

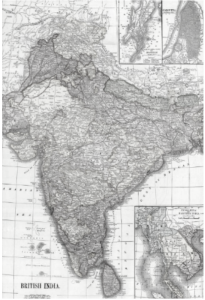

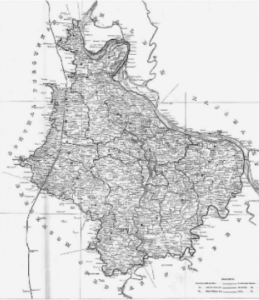

British India.

PROVINCE/PRESIDENCY.

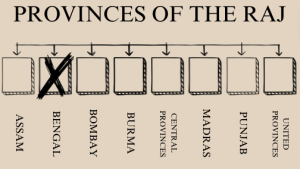

About a dozen Provinces made up the whole of British India, that is, the part of India under immediate British rule. The Provinces had their headquarters in Calcutta, and the Himalayan Hill-Station of Simla during the hot season. “Besides these directly-governed provinces,” Charley writes, “there is a huge native India of six hundred thousand square miles, ruled by Hindu or [Muslim] or Buddhist princes.” The seven Provinces of India during the time of Charley were: Assam, Bengal, Burma, Central Provinces, Madras. Punjab, and the United Provinces.

Provinces of the Raj

Bengal Presidency, India.

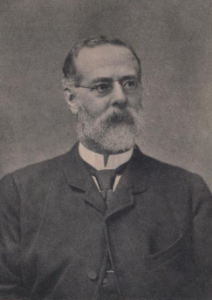

Charley was stationed in Bengal which was administered by Sir Steuart Colvin Bayley, Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal from 1887 to 1890.

Sir Steuart Colvin Bayley, Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal from 1887 to 1890.

DIVISION.

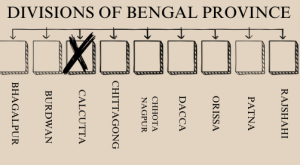

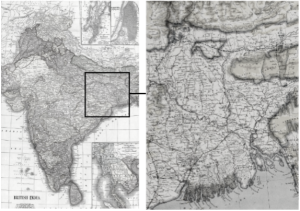

Each Province was further divided into Divisions (usually about six,) which were administered by a Commissioner. In Bengal the nine Divisions of the Bengal Presidency (Province) were Bhagalpur, Burdwan, Calcutta (of Presidency Division,) Chittagong, Chota Nagpur, Dacca, Orissa, Patna, Rajshahi.) Charley was stationed in the Calcutta Division, also known as the Presidency Division, which was administered by Alexander Smith, Commissioner.

Calcutta. [Presidency Division]

DISTRICT.

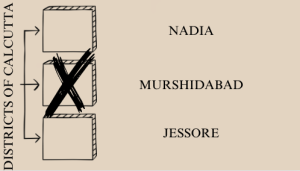

Division were divided into Districts (usually around ten,) and administered by Collectors. The District was the unit of government (both for taxation and courts of justice,) with a population averaging about 1,000,000. It was largely administered by well-paid native officials, under British control. The Head of the District held both the titles of Collector and Magistrate, whose role it was to collect revenue, and to maintain general order. Typically the Collector was aided by a District Judge, a Joint Magistrate, along with one or two Junior Deputies and Assistant Magistrates. Additionally, there were three influential British officials at the central station of each District, but they were not Covenanted Civilians. They were the Civil Engineer, the Civil Surgeon, Surgeon, and the District Superintendent of Police. The Districts of the Calcutta Division were Jessore, Nadia, and Murshidabad. Charley was stationed in Murshidabad.

The Collector of Murshidabad when Charley first arrived was Godfrey John Bective Tuite-Dalton, an Irishman from Cavan, Ireland and fellow graduate of Trinity College, Dublin. The Civil Engineer was Charles E. Livesay, the Civil Surgeon was Surgeon-Major F.C. Nicholson, and the District Superintendent of Police was G.R.E. Meares. The system of police administration in Bengal made the Inspector in charge of each division of a District responsible to the Superintendent of Police for the peace of his division. He was, however, essentially a peripatetic officer, and his duties were those of inspection only, except in serious cases where his presence was urgently required. Subordinate to him was the Sub-Inspector in charge of a thana, and again, subordinate to the Sub-Inspector was the Head Constable in charge of an outpost or section of a thana. The Sub-Inspector and the Head Constable were the officers usually employed in the investigation of crime, and subordinate to them were police constables who vary in number according to the size and importance of the station at which they were posted. Subsidiary to the regularly enrolled police were the rural police, whose chief function was to see that the occurrence of crime in the village to which they belonged was promptly reported to the police station.

SUBDIVISION.

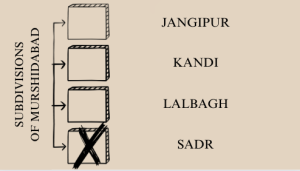

Districts were further divided into Subdivisions (usually between four and five.) and administered by Collectors. In Murshidabad this included Berhampore/Sadr Station (Headquarters Subdivision and capital of the District,) where the courts and offices of the Sadr Station were located, and where Charley was stationed. At each Sadr a native Sub-Judge was responsible for adjudicating many civil cases, and their salary was twice that of a newly appointed Covenanted Civilian, such as Charley. The other Subdivisions in the Murshidabad District were Lalbagh, Kandi, and Jangipur.

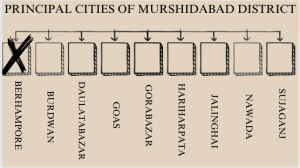

Two or three native Deputy Magistrates, whose responsibilities were equal to the young Civilians, presided over the Subdivisions, until “a youthful Civilian, who had learned the rudiments of his work and had gained some familiarity with the spoken tongue, was put in charge of a Subdivision to gain further experience.” The principal municipalities of the Subdivisions included: Berhampore, Burdwan, Daulatabazar, Goas, Gorabazar, Hariharpata, Jalinghai, Nawada, Sujaganj.

PANCHAYAT

At the lowest rungs of the administrative ladder were the panchayat, and elected officials in a limited self-government (more on that later.) Charley writes:

There were, in every district, at least four types of bodies having activities that were genuinely legislative. Beginning with the simplest, there was in every village the elected panchayat, lineal descendant of the self-governing body in the age-old village community.

Next came the elected local board, for each subdivision, not indigenous, but quite recently overlaid on the native life by the British administrators.

Then there was an elected district board, with supervision over roads, bridges, hospitals, and schools, and with power to raise local taxes. These district boards had in them the germs of the county councils of modern England, themselves remote successors of the Saxon shire mote. Finally, the municipalities were governed by elected bodies, predominantly native. So there were […] elements of self-government in India, as well as opportunities for qualified natives to share in the daily work of administration. All these elements might well have developed along indigenous lines.

LORD DUFFERIN’S SPEECH.

A British perspective on the Raj during this period can be gleaned from a farewell speech given by Lord Dufferin, the departing Viceroy, on the November 30, 1888, just days after Charley arrived in India.

“I do not intend to trouble you tonight with egotistical references to my own administration, or with any attempt to vindicate the general policy of the Government of India. The verdict upon both has passed out of my hands, and it will be the pen of the historian that will determine whether my colleagues and myself have succeeded in any adequate degree in contributing to the peace and security of the country, in dissipating some formidable dangers, and in inaugurating such reforms and improvements in its administration as the time and the circumstances of the case either permitted or required. Of one thing, at all events, I am certain we have done a great deal more in these directions than is generally supposed.

BURMA.

“Still there is one misapprehension into which the public has fallen, which I am desirous of taking this opportunity of correcting once for all, lest it should crystallize into a popular belief, and that is that the difficulties which we have had to encounter in Burma [Third Anglo-Burmese War] arose from an attempt of the Indian Government to effect the conquest of that kingdom in too economical a manner, or, to use a vulgar expression, “on the cheap.” Such an idea is entirely unfounded. There may have been mistakes, but they did not arise from that source. On the contrary, the Government of India has never, from first to last, refused the local authorities of Burma a single requisition, whether for money, for troops, for civil officers, or for police, which they have ever submitted to us. Nay more, we encouraged them from time to time to make further demands on us in every one of these respects.

The nominal surrender of the Burmese Army, November 27, 1885.

“With regard to the strength of the original force, it must be remembered that the expedition to Mandalay was essentially a riverine expedition, and that the number of troops that could be despatched upon it was limited by the riverine transport at our disposal. Though the means of transport afforded us by the existence of the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company were very considerable, they had to be strained to the utmost extent. Happily, they were amply sufficient for the immediate purpose in view, as was shown by the surrender of the Burmese army, the capture of the king, and the occupation of his capital in the course of a fortnight. The very day that Mandalay was taken we telegraphed to both our civil and military representatives to inquire whether or not the additional reinforcements which we had ready to start in support should be sent off; but both the civil and the military authorities considered that the forces at their disposal were sufficient for all immediate requirements.

Junior Queen Supayalay next to Queen Supayalat and King Thibaw (November 1885)

“The difficulties which subsequently occurred were not difficulties which could be overcome by the application of mere brute force as represented by numbers. They were inherent in the very nature of the case, the enormous extent of the country, its complete disorganization, the absence of all roads, and the vastness and impracticability of the jungles. Impediments like these could not be successfully dealt with at once, especially as the rainy season soon intervened to hamper our endeavours. Roads had to be cut, telegraphic communications established, military posts constructed, and a hundred other preliminary arrangements introduced. Above all, a military police had to be organized, for the Government of India does not keep on hand, as a grocer does pepper, a ready-made supply of military police for casual emergencies. Such a body, who are the real restorers of order, have to be painfully and laboriously enlisted and drilled. In spite of all these difficulties, as Sir Alec Wilson has stated, within a little more than two years and a half, we have succeeded not only in tranquillizing the country but in furnishing it forth with all the appliances of a civilized state. All the big dacoit bands have been dispersed, and their leaders disposed of. Crime in Lower Burma is now less than it was before the war, and even the return of the dry season has not shown any perceptible recurrence of it in Upper Burma. It is true that, during the winter we shall have to punish some of the wild mountain tribes, both in the north and in the west, who have been raiding Burmese villages and head-hunting on Burmese territory. But these troubles are as common to the borders of India as they are to those of Burma.

“Burmese prisoners readied for execution, 1880s.”

“If we remember that, when Lord Dalhousie took possession of Pegu [during the Second Anglo-Burmese War] though he undoubtedly displayed in everything he undertook the greatest vigour and energy, and though Pegu was only a sixth of the size of the country that we have recently dominated it took him seven or eight years to reduce it to reasonable submission, I think we may be satisfied with the result. Indeed, it was only the other day that I was reading a life of Lord Minto, who mentions incidentally that in his time whole districts within twenty miles of Calcutta were at the mercy of dacoits, and this after the English had been more than fifty years in the occupation of Bengal; while, even in our own days, large bands of robbers in Central India are baffling all the efforts of the Indore Government to put an end to their depredations. The fact is dacoity is a peculiar sort of crime, and one far more difficult to deal with than even the organized opposition of regular armies. I have been led to dilate more fully upon this subject than I had intended; but I have felt it my duty to do so, not so much in the interests of the Indian administration as from a desire to vindicate the conduct of those eminent civil and military officers who, in the teeth of a great deal of misapprehension, have been carrying out with exceptional ability, and with acknowledged success, their responsible and thank-less duties. And now, gentlemen, what else am I to say to you? As a rule, I do not think it is a desirable thing for the Viceroy of India to make speeches. I have carefully avoided doing so as much as possible; but perhaps, as I am so near the day of my dissolution, I may be permitted to utter a few words of warning and advice to those to whose affairs I have been giving such unremitting attention for so long a period. You will understand, therefore, that it is not so much the Viceroy that is addressing you as a departing, pale, and attenuated shade, or rather, shall we say, some intelligent traveler who has come to India for three months, with the intention of writing an encyclopedic work on its Government and its people, and who is therefore able to speak in a spirit of infallibility denied to us lesser men.

WHAT IS INDIA?

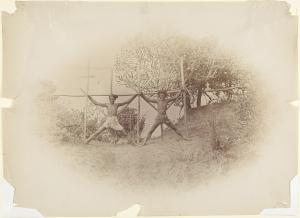

“Well then, gentlemen, what is India? It is an Empire equal in size, if Russia be excluded, to the entire continent of Europe, with a population of 250,000,000 souls, composed of a large number of distinct nationalities, professing various religions, practicing diverse rites, and speaking different languages—the Census Report says there are 106 different Indian tongues—not dialects—of which eighteen are spoken by more than a million persons, while many races are still farther separated from each other by discordant prejudices, conflicting social usages, and even antagonistic material interests. Perhaps the most patent peculiarity of our Indian Cosmos is its division into two mighty political communities—the Hindus, numbering 190,000,000, and the Mahomedans, 50,000,000, whose distinctive characteristics, religious, social, and ethnological, it is unnecessary to mention. To these two great divisions must be added a host of minor nationalities, though some are included in the two broader categories, are as completely differentiated from each other as Hindus from Mahomedans. Such are the Sikhs, with their warlike habits and traditions and theocratic enthusiasm; the Rohillas, Pathan, Assamees, Belochees, and other wild and martial tribes on the frontiers; the hillmen dwelling on the Himalayas; our subjects in Burmah. Mongol in race and Buddhist in religion; the Khonds, Mairs, Bheels, and other non-Aryan peoples of the center and south of India, and the enterprising Parsees, with their rapidly developing manufactures and commercial interests. Again, amongst these numerous communities may be found at one and the same moment all the various stages of civilization through which mankind has passed from the prehistoric ages to the present day. At one end of the scale we have the naked savage hillman, with his stone weapons, his head-hunting, his polyandrous habits, and his childish superstitions; and at the other, the Europeanized native gentleman, with his refinement and polish, his literary culture, his Western philosophy, and his advanced political ideas; while between the two lie, layer upon layer, or in close juxtaposition, wandering communities, with their flocks of goats and moving tents; collections of undisciplined warriors, with their blood feuds, their clan organization and loose tribal government; feudal chiefs and barons, with their picturesque retainers, their seignorial jurisdiction, and their mediaeval modes of life; and modernized country gentlemen, and enterprising merchants and manufacturers, with their well-managed estates and prosperous enterprises. Besides all these, who are under our direct administration, the Government of India is required to exercise a certain amount of supervision over the one hundred and seventeen native states, with their princely rulers, their autocratic executives, their independent jurisdictions, and their fifty millions of inhabitants. The mere enumeration of these diversified elements must suggest to the most unimaginative mind a picture of as complicated a social and political organization as ever tasked human ingenuity to govern and administer. But, even within British India in the narrower sense of the term, we have not reached the limits of our accountability, for we are bound to provide for the safety and welfare not only of Her Majesty’s Hindu, Mahomedan, and other native subjects, but also of the large East Indian community, of the indigenous Christian Churches, of the important planting and manufacturing interests which are scattered over the face of the country, as also to secure the property and lives of all the British residents in India, men, women, and children, whether employed in the service of the Government or pursuing independent avocations in the midst of the alien and semi-civilized multitudes whose peaceable and orderly behaviour cannot, under all circumstances, be implicitly relied on.

ENORMOUS COMMERCIAL INTERESTS.

“To these obligations must also be added the duty of watching over the enormous commercial interests of the mother country, represented by a guaranteed capital of over two hundred and twenty millions of pounds sterling, which, to the great benefit of India, has been either lent to the State or sunk in Indian railways and similar enterprises; for it would be criminal to ignore the responsibility of the Government towards those who have sunk large sums of money in the development of Indian resources on the faith of official guarantees, or who have invested their capital in the Indian funds at the invitation of the Imperial Indian authorities. The same considerations apply with almost equal force to that further vast amount of capital which is employed by private British enterprise in manufactures, in tea planting, and in the indigo, jute, and similar industries, on the assumption that English rule and English justice will remain dominant in India.

Calcutta 1880s.

“If, again, we turn our eyes outwards, it will be found that our external obligations are hardly less onerous and imperative than those confronting us from within. India has a land frontier of nearly 6,000 miles, and a seaboard of about 9000 miles. On the east she is conterminous with Siam and China, on the north with Tibet, Bhutan, and Nepal, and on the west she marches, at all events diplomatically, with Russia. On her coast are many rich and prosperous seaports—Calcutta, Bombay, Madras, Karachi, Rangoon—and every year we are made more painfully aware to how serious an extent our contiguity with foreign nations, whether civilized or uncivilized, and the complications arising both out of Eastern and Western politics, may expose us to attack. Every day we feel more keenly the necessity of walking both warily and wisely in respect of our international relations, and of taking those precautions, however onerous or expensive, which are incumbent on every nation that finds itself in contact with enterprising military monarchies or rival maritime powers. It is then for the outward protection and for the internal control it is for the welfare, good government, and progress of this congeries of nations, religions, tribes, and communities, with the tremendous latent forces and disruptive potentialities which they contain, that the Government of India is answerable; and it is in reference to the ever-shifting and multiplying requirements of this complicated political organization that it has been called upon from time to time to shape and modify its system of administration.

“In the earlier stages of England’s connection with India, and even after the force of circumstances had transmuted the East India Company of merchants into an Imperial Executive, the ignorance and the disorganization of the peninsula consequent upon the anarchy which followed the collapse of the Mahomedan regime necessitated the maintenance of a strong uncompromising despotism, with the view of bringing order out of chaos, and a systematized administration out of the confusion and lawlessness which were then universally prevalent. But such principles of government, however necessary, have never been congenial to the instincts or habits of the English people.

“As soon as the circumstances of the case permitted, successive statesmen, both at home and in India itself, employed themselves from time to time in softening the severity of the system under which our dominion was originally established, and strenuous efforts were repeatedly made, not only to extend to Her Majesty’s subjects in India the same civil rights and privileges which are enjoyed by Her Majesty’s subjects at home, but to admit them, as far as was possible, to a share in the management of their own affairs. The proof of this is plainly written in our recent history. It is seen in our legal codes, which secure to all Her Majesty’s subjects, without distinction of race or creed or class, equality before the law. It is found in the establishment of local legislative councils a quarter of a century ago, wherein a certain number of leading natives were associated with the Government in enacting measures suitable to local wants. It lies at the basis of the great principle of decentralized finance, which has prepared the way for the establishment of increased local responsibility. It received a most important development in the municipal legislation of Lord Northbrook’s administration. It took a still fuller and more perfect expression during the administration of my distinguished predecessor, in the Municipal and Local Boards Acts; and it has acquired a further illustration in the recommendation of the Public Service Commission, recently sent home by the Government of India, in accordance with which more than a hundred offices hitherto reserved to the Covenanted Service would be thrown open to the Provincial Service, and thus placed within the reach of our native fellow-subjects in India.

DEMOCRATIC METHODS OF GOVERNMENT.

“And now, gentlemen, some intelligent, loyal, patriotic, and well-meaning men are desirous of taking, I will not say a further step in advance, but a very big jump into the unknown by the application to India of democratic methods of government, and the adoption of a parliamentary system, which England herself has only reached by slow degrees and through the discipline of many centuries of preparation.

“The ideal authoritatively suggested, as I understand, is the creation of a representative body or bodies in which the official element shall be in a minority, who shall have what is called the power of the purse, and who, through this instrumentality, shall be able to bring the British executive into subjection to their will. The organization of battalions of native militia and volunteers for the internal and external defence of the country is the next arrangement suggested, and the first practical result to be obtained would be the reduction of the British army to one half its present numbers. Well, gentlemen, I am afraid that the people of England will not readily be brought to the acceptance of this programme, or to allow such an assembly, or a number of such assemblies, either to interfere with its armies, or to fetter and circumscribe the liberty of action either of the provincial governments or of the Supreme Executive.

“In the first place, the scheme is eminently unconstitutional; for the essence of constitutional government is that responsibility and power should be committed to the same hands. The idea of irresponsible councils, whose members could arrest the march of Indian legislation, or nullify the policy of the British executive in India, without being liable to be called to account for their acts in a way in which an opposition can be called to account in a constitutional country, must be regarded as an impracticable anomaly.

“Indeed, so obviously impossible would be the application of any such system in the circumstances of the case, that I do not believe it has been seriously advocated by any native statesman of the slightest weight or importance. I have come into contact, during the last four years, with, I imagine, almost all the most distinguished persons in India. I have talked with most of them upon these matters, and I have never heard a suggestion from one of them in the sense I have mentioned.

“But if no native statesman of weight or importance, capable of appreciating the true interests of England and of India, is found to defend this program, who are those who do? Who and what are the persons who seek to assume such great powers to tempt the fate of Phaeton, and to sit in the chariot of the Sun? Well, they are gentlemen of whom I desire to speak with the greatest courtesy and kindness, for they are, most of them, the product of the system of education which we ourselves have carried on during the last thirty years. But thirty years is a very short time in which to educe a self-governing nation from its primordial elements. At all events, let us measure the extent of educated assistance upon which we could call at this moment; let us examine the degree of proficiency which the educated classes of India have attained and the relation of their numbers to the rest of the population. Out of the whole population of British India, which may be put at 200 millions in round numbers, not more than five or six percent, can read and write, while less than one per cent, has any knowledge of English. Thus, the overwhelming mass of the people, perhaps one hundred and ninety out of the two hundred millions, are still steeped in ignorance, and of the ten or twelve millions who have acquired education, three-fourths have attained to merely the most elementary knowledge.

“In our recent review of the progress of education, it was pointed out that ninety-four and a half percent, of those attending our schools and colleges were in the primary stage, while the progress made in English education can be measured by the fact that the number of students who have graduated at the universities since their establishment in 1857 that is, during the course of the last thirty-one years is under eight thousand. During the last twenty-five years probably not more than half a million students have passed out of our schools with a good knowledge of English, and perhaps a million more with a smattering of it. Consequently, it may be said that, out of a population of 200 millions, there are only a very few thousands who may be considered to possess adequate qualifications, so far as education and an acquaintance with Western ideas or even Eastern learning are concerned, for taking an intelligent view of those intricate and complicated economic and political questions affecting the destinies of so many millions of men which are almost daily being presented for the consideration of the Government of India.

“I would ask, then, how any reasonable man could imagine that the British Government would be content to allow this microscopic minority to control their administration of that majestic and multiform empire for whose safety and welfare they are responsible in the eyes of God and before the face of civilization? It has been stated that this minority represents a large and growing class. I am glad to think that it represents a growing class, and I feel very sure that, as time goes on, it is not only the class that will grow, but also the information and experience of its members. At present, however, it appears to me a groundless contention that it represents the people of India. If they had been really representatives of the people of India that is to say, of the voiceless millions instead of seeking to circumscribe the incidence of the income tax, as they desired to do, they would probably have received a mandate to decuple it. Indeed, is it not evident that large sections of the community are already becoming alarmed at the thought of such self-constituted bodies interposing between themselves and the august impartiality of English rule? These persons ought to know that in the present condition of India there can be no real or effective representation of the people, with their enormous numbers, their multifarious interests, and their tessellated nationalities. They ought to see that all the strength, power, and intelligence of the British Government are applied to the prevention of one race, of one interest, of one class, of one religion, dominating another; and they ought to feel that in their peculiar position there can be no greater blessing to the country than the existence of an external, dispassionate, and immutable authority, whose watch- word is Justice, and who alone possesses both the power and the will to weld the rights and status of each separate element of the empire into a peaceful, co-ordinated, and harmonious unity. When the [Indian National] Congress was first started, I watched its operations with interest and curiosity, and I hoped that in certain fields of useful activity it might render valuable assistance to the Government.

SOCIAL TOPICS CONNECTED WITH THE HABITS AND CUSTOMS OF THE PEOPLE.

“I was aware that there were many social topics connected with the habits and customs of the people which were of unquestionable utility, but with which it was either undesirable for the Government to interfere, or which it was beyond their power to influence or control. For instance, where is there a population whose rise in the scale of social comfort and prosperity is more checked and impeded by excessive and useless expenditure on the occasion of marriages and other similar ceremonies than that of India? Or in what country is the peasant more hampered in the pursuit of his agricultural industry, than is the Hindu or Mahomedan ryot, by chronic indebtedness to the money-lenders? Where is there a more crying need for sanitary reform than amongst those who insist upon bathing in the tanks from which they obtain their drinking-water, and where millions of men, women, and children die yearly, or, what is even worse, become the victims of chronic debility, disease, and racial deterioration, from preventable causes? What system could be named more calculated to cause greater searchings of the heart than some of the domestic arrangements so ruthlessly insisted upon by Hindu society? Above all, what land is exposed to such imminent danger by the overflow of the population of large districts and territories whose inhabitants are yearly multiplying beyond the number which the soil is capable of sustaining? To this last topic I am especially anxious to call the attention of every lover of his country. The danger has long since been signalized by European writers, especially by that most acute of all observers, the late Sir Henry Maine; and it was almost the first subject that attracted my attention when I came to India. Perhaps the widespread misery which I had witnessed in Ireland, produced by similar conditions, had quickened my observation.

Sir William Wilson Hunter.

“I first of all commissioned Sir William Hunter to take the matter up, and after his departure the task of dealing with it was confided to Sir Edward Buck. A committee met at Delhi, and at the same time provisional reports were called for from various governments on the general condition of the people. The short resolution in which the general tendency of these reports and the lessons to be derived from them are contained, has, I understand, been denounced as an endeavour of the Government to impart a rose-coloured view to the situation. All I can say is that in ordering the inquiry my object was to obtain the means of awaking public opinion in India to the gravity and danger of our position, rather than to lull it into fancied security, and any one who can derive much satisfaction from the result must be either of a very sanguine or a very callous temperament; for although it has been clearly demonstrated that those who represent the poorer classes of India as universally living in a chronic state of semi-starvation and inanition, grossly exaggerate, and that the condition of these classes has been steadily improving, it is undoubtedly the case that in certain districts, whose inhabitants are to be numbered by millions, the means of sustenance provided by the soil are inadequate for the support of those who live upon it.

EXPANSION OF MANUFACTURING INDUSTRIES, AND EMIGRATION.

“When we reflect that, in the most thickly populated districts of Europe, there are only from 400 to 500 persons to the square mile, whereas in the localities I am referring to they exceed 700 and even 800 to the square mile, we shall be better able to appreciate the reality of the danger. Well, then, gentlemen, for such a state of things there are only two remedies—the expansion of manufacturing industries, and emigration. But it is not in the power of the Government of itself to apply either of these remedies. By removing, restrictions on trade, and by the multiplication of roads, railways, and the facilities of conveyance, we can foster manufacturing and mercantile activity, which we are doing; but the actual creation of manufacturing centers must be the work of private enterprise. To the same imperfect degree, and principally by the same means, the Government can promote emigration. It can let or sell land under favourable conditions to would-be settlers. It can indicate the places where population is superabundant, and where comparatively unoccupied tracts are to be found; but it can neither prohibit by law imprudent marriages, nor compel the inhabitants of a village in any particular locality to transfer themselves to another. But what the Government cannot do, the gentlemen to whom I am referring might very usefully employ themselves in doing. They know the ways and habits of the people; they know the nature of their occupations; they know their needs; and as they themselves come from different parts of India, they know where labour is scarce, where land is plentiful, and where the newcomers could be best accommodated either as cultivators or as coolies. By carefully examining the elements of the problem, they might put themselves into a position to place at the disposal of the Government both useful information and advice.

LATEST PRINCIPLES OF WESTERN HYGIENE.

“Again, with regard to sanitation. And by sanitation I do not mean the inopportune and injudicious worrying and harrying of our villagers into the adoption of uncongenial ways and habits, or the forcing upon them of the latest principles of Western hygiene, but a gradual patient process similar to that which has banished cholera, jail fever, and many other ills from England during the course of the present century, and which consists in placing pure water within the reach of the people, and in indoctrinating them with those simple rules which add as much to the comfort as they do to the decency of domestic life. The Government has recently given its serious attention to this subject, and has laid down the lines upon which, in its opinion, sanitary reform should be applied to our towns and villages. It has given sanitation a local habitation and a name in every great division of the empire; and it has arranged for the establishment of responsible central agencies from one end of the country to the other, who will be in close communication with all the local authorities within their respective jurisdictions. But, after all, the most earnest endeavours both of the Supreme and of the Provincial Governments will be of little avail, unless seconded by the intelligent co-operation of the educated native classes.

TECHNICAL EDUCATION.

“So again with regard to technical education. The Government of India may recommend to the local governments the policy and the arrangements which it considers to be suited for the establishment and spread of this useful and necessary branch of instruction, and the local governments may improve upon those suggestions, or may apply them with the utmost zeal and wisdom; but it is the educated classes those who are most intimately acquainted with the internal economy of the homes of India and the natural aptitudes of their inhabitants who alone can give energy and vitality to the movement. Well, gentlemen, as I have already observed, when the Congress was first started, it seemed to me that such a body, if they directed their attention with patriotic zeal to the consideration of these and cognate subjects, as similar Congresses do in England, might prove of assistance to the Government and of great use to their fellow-citizens; and I cannot help expressing my regret that they should seem to consider such momentous topics, concerning as they do the welfare of millions of their fellow-subjects, as beneath their notice, and that they should have concerned themselves instead with matters in regard to which their assistance is likely to be less profitable to us.

“It is a still greater matter of regret to me that the members of the Congress should have become answerable for the distribution as their officials have boasted amongst thousands and thousands of ignorant and credulous men of publications animated by a very questionable spirit, and whose manifest aim is to excite the hatred of the people against the public servants of the Crown in this country. Such proceedings as these no Government could regard with indifference, nor can they fail to inspire it with misgivings, at all events with regard to the wisdom of those who have so offended. Nor is the silly threat of one of the chief officers the principal secretary, I believe of the Congress, that he and his Congress friends hold in their hands the keys not only of a popular insurrection but of a military revolt, calculated to restore our confidence in their discretion, even when accompanied by the assurance that they do not intend for the present to put these keys into the locks. But, gentlemen, though I have thought it my duty in these plain terms to point out what I consider the misapprehension of the Congress party as to the proper direction in which their energies should be employed, I do not at all wish to imply that I view with anything but favour and sympathy the desire of the educated classes of India to be more largely associated with us in the conduct of the affairs of their country. Such an ambition is not only very natural, but very worthy, provided due regard be had to the circumstances of the country and to the conditions under which the British administration in India discharges its duties. In the speech which I delivered at Calcutta on the occasion of Her Majesty’s jubilee, I used the following expression:

Wide and broad, indeed, are the new fields in which the Government of India is called upon to labour, but no longer, as of aforetime, need it labour alone. Within the period we are reviewing, education has done its work, and we are surrounded on all sides by native gentlemen of great attainments and intelligence, from whose hearty, loyal, and honest co-operation we may hope to derive the greatest benefit. In fact, to an administration so peculiarly situated as ours, their advice, assistance, and solidarity are essential to the successful exercise of its functions. Nor do I regard with any other feelings than those of approval and good-will their natural ambition to be more extensively associated with their English rulers in the administration of their own domestic affairs ; and glad and happy should I be if, during my sojourn amongst them, circumstances permitted me to extend and to place upon a wider and more logical footing the political status which was so wisely given a generation ago by that great statesman, Lord Halifax, to such Indian, gentlemen as by their influence, their acquirements, and the confidence they inspired in their fellow-countrymen, were marked out as useful adjuncts to our Legislative Councils.

“To every word which I then spoke I continue to adhere; but surely the sensible men of the country cannot imagine that even the most moderate constitutional changes can be effected in such a system as ours by a stroke of the pen, or without the most anxious deliberations, as well as careful discussions in Parliament. If ever a political organization has existed where caution is necessary in dealing with those problems which affect the adjustment of the administrative machine, and where haste and precipitancy are liable to produce deplorable results, it is that which holds together our complex Indian Empire; and the man who stretches forth his hand towards the ark, even with the best intentions, may well dread lest his arm should shrivel up to the shoulder. But growth and development are the rule of the world’s history, and from the proofs I have already given of the way in which English statesmanship has perpetually striven gradually to adapt our methods of government in India to the expanding intelligence and capacities of the educated classes amongst our Indian subjects, it may be confidently expected that the legitimate and reasonable aspirations of the responsible heads of native society, whether Hindu or Mahomedan, will in due time receive legitimate satisfaction. The more we enlarge the surface of our contact with the educated and intelligent public opinion of India, the better; and although I hold it absolutely necessary, not merely for the maintenance of our own power, but for the good government of the country, and for the general content of all classes, and especially of the people at large, that England should never abdicate her supreme control of public affairs, or delegate to a minority or to a class the duty of providing for the welfare of the diversified communities over which she rules, I am not the less convinced that we could, with advantage, draw more largely than we have hitherto done on native intelligence and native assistance in the discharge of our duties. I have had ample opportunities of gauging and appreciating to its full extent the measure of good sense, of practical wisdom, and of experience which is possessed by the leading men of India, both among the great nobles on the one hand, and amongst the leisured and professional classes on the other, and I have now submitted officially to the home authorities some personal suggestions in harmony with the foregoing views.

CONSTITUTION OF THE POLICE.

“Gentlemen, I have sometimes seen in the newspapers formidable indictments drawn up against the British administration in India. I do not now refer to them for the purpose of controverting the charges which they formulated, but they have certainly indicated one blemish which the Government of India frankly recognises and had already begun to deal with; namely, the present constitution of the police. There are undoubtedly great defects in this branch of the public service. It is, however, by no means an easy matter to deal with. The difficulty lies in the low morale prevailing in the classes from which alone the police can be drawn, in the supineness and ignorance of the people themselves, and, still more, the additional expenditure which would be entailed by any really effective amelioration of the force. Again, with regard to the separation of judicial and executive offices in the early stage of the service and in the lower grades. This is a counsel of perfection to which we are ready to subscribe, though the reform suggested, where it has not been carried into effect and it has been largely effected is by no means so simple a proceeding as many people suppose. And here also we have a question of money. With regard to both these subjects, however, I have to make one observation. The evils complained of are not of recent date : they existed long before my time, and had they been as intolerable as is now stated, they would have been remedied while the existence of surplus funds rendered this practicable ; but, as this was not done, it is fair to argue that, even admitting that there is room for improvement in both the above respects, we can afford to consult times and seasons in carrying these improvements into effect. Be that, however, as it may, I confess I always lay down these incriminating documents with a feeling of relief at finding that more serious shortcomings cannot be alleged against us.

“When I consider the difficulties of our task, the imperfection of the instruments through which we must necessarily work, the multiplicity of the interests with which we have to deal, the liability of our most careful calculations to be overset by material accidents over which we have no command, the complexity and centrifugal might of the forces we are called upon to harmonize and co-ordinate, the extraordinary tendency in the East for two and two to make five, and the imperfection which stamps the conduct of all human affairs, my wonder is that our miscarriages should not have been infinitely multiplied. In reading these criticisms I am reminded of a story of a young man who afterwards became a very powerful public speaker. On his first appearance on the hustings he was so embarrassed by the novel circumstances of his situation that he made but an indifferent attempt at a speech; but when some one in the crowd ill-naturedly jeered at him, he cried out, “You just come up here and do it yourself you won’t find it so easy,” which pertinent observation at once won for him the sympathy of his audience. At all events, we have the satisfaction of knowing that there is another side to the picture; for in these diatribes, to use Sir Auckland Colvin’s eloquent words:

Of the India of today as we know it; of India under education; of India compelled, in the interests of the weaker masses, to submit to impartial justice; of India brought together by road and rail; of India entering into the first-class commercial markets of the world; of India of religious toleration; of India assured, for terms of years unknown in less fortunate Europe, of profound and unbroken peace; of India of the free press; of India finally taught for the first time that the end and aim of rule is the welfare of the people and not the personal aggrandisement of the sovereign.

“He might have added of India that within the last twenty- eight years has accumulated 110 millions of gold and 218 millions of silver, ” we fail to find a syllable of recognition.” At all events, gentlemen, you may be sure that whatever our sins, whether of omission or of commission, the English Government in India will continue faithfully, courageously, and in the fear of God to endeavour to discharge its duties, to amend whatever may be amiss, and still further to improve the good which already exists, indifferent to praise or blame, and as unresentful of the hard things occasionally said of us by those for whose sake we are labouring, as we shall always be grateful for the appreciation of those and they are the great majority—of our Indian fellow-subjects who have the intelligence to understand and the generosity to acknowledge what we have done for them. And now, gentlemen, it only remains for me to thank you not only for your hospitality and for the friendly reception you have given to the mention of Lady Dufferin’s name and my own, but for the patience with which you have listened to this somewhat lengthy speech. It is a great regret to me to think that I am looking round for the last time upon so many friendly and familiar faces. In another week I shall have discharged my trust, and transferred my great office to the hands of one of England’s most capable statesmen, a nobleman in the prime of life, and already distinguished for his sound judgment, his moderation, his wisdom, and the industry with which he applies himself to public affairs. That he will by the intelligence, the impartiality, and the sympathetic character of his rule gain and maintain the good- will and the confidence both of Her Majesty’s native and English subjects in India, I have not the slightest doubt, and this conviction to a great extent consoles me for my regret in quitting your service. Gentlemen, I again thank you from the very bottom of my heart for all your kindness and goodness.”

⸻

AGONISED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS.

INTRO: CHARLEY.

I. WITCH TALES.

II. CARELESS WHENCE COMES YOUR GOLD.

III. THE TIMES ARE CHANGED.

IV. DENIZEN OF ETERNITY.

V. DOMOVOY.

[APPENDICES]

THE ENGLISH IN INDIA III.

SOURCES:

“Jails.” The Madras Weekly Mail. (Madras, India.) August 6, 1887.

“Occasional Notes.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (Calcutta, India) June 22, 1889.

“Crime In Bengal.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (Calcutta, India) June 17, 1890.

(Lord Dufferin) Blackwood,Frederick Temple. Speeches Delivered in India, 1884-1888. John Murray. London, England. (1890): 229-248.

Hart, H.G. Hart’s Annual Army List, Militia List, And Imperial Yeomanry List, And Indian Civil Service List, For 1890. John Murray. London, England. (1890): 892.

Hunter, W. W. The Imperial Gazetteer Of India Vol. X. Trübner & Co. London, England (1886): 20-39.

Johnston, Charles. “Helping To Govern India.” Proceedings of the American Political Science Association, 1906, Vol. III., Third Annual Meeting. (1906): 169-179.

Johnston, Charles. “The English In India.” The North American Review. Vol. CLXXXIX, No. 642 (May 1909): 695- 707.

Johnston, Charles. “Fuller Liberty For India.” The North American Review. Vol. CCIX., No. 763 (June 1919): 772-780.

Johnston, Charles. “A Perspective On India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXXXVIII, No. 6. (December 1926): 848-856.

Johnston, Charles. “India A Dominion?” The North American Review. Vol. CCXXV., No. 842. (April 1928): 385-393.

O’Donnell, C. J. Census Of India, 1891 Vol III: The Lower Provinces Of Bengal. Bengal Secretariat Press. Bengal, India. (1893): 91.

Walsh, J.H. Tull. A History Of Murshidabad District (Bengal): With Biographies Of Some Of Its Noted Families. Jarrold & Sons. London, England. (1902): 38.

[Godfrey John Bective Tuite-Dalton] Ancestry.com. India, Select Marriages, 1792-1948 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.