THE TIMES ARE CHANGED

III.

⸻

Joshiji was a shrewd and learned Brahman who, in addition to be an adviser to Moniya’s family, was an old friend. Joshiji maintained his connection with the family, even after the death of Moniya’s father, so it came as no surprise when he called on the family during Moniya’s break from school. Learning that Moniya was enrolled at Samaldas College, he asked Moniya’s mother, Putlibai, and elder brother, Laxmidas, about his studies.

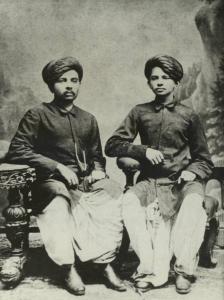

(Left) Laxmidas & (Right) Moniya c. 1885.

“The times are changed,” said Joshiji. “None of you can expect to succeed to your father’s gadi without having had a proper education. Now as this boy is still pursuing his studies, you should all look to him to keep the gadi. It will take him four or five years to get his bachelor’s degree, which will at best qualify him for a sixty rupees’ post, not for a Dewanship. If like my son he went in for law, it would take him longer still, by which time there would be a host of lawyers aspiring for a Dewan’s post. I would far rather that you sent him to England. My son Kevalram says it is very easy to become a barrister. In three years’, time he will return. Also, expenses will not exceed four to five thousand rupees. Think of that barrister who has just come back from England. How stylishly he lives! He could get the Dewanship for the asking. I would strongly advise you to send Moniya to England this very year. Kevalram has numerous friends in England. He will give notes of introduction to them, and Moniya will have an easy time of it there.”

Joshiji turned to Moniya with complete assurance. “Would you not rather go to England than study here?” he asked.

Many thoughts came to Moniya’s mind. He and his wife, Kasturbai, were expecting a baby in a few weeks’ time. Moniya was only nineteen years old, but he and Kasturbai already lost a child, their first, in 1885.

“The sooner I am sent, the better,” said Moniya, jumping at the proposal. “But it is no easy business to quickly pass examinations quickly. Could I not be sent to qualify for the medical profession?”

“Father never liked it,” said Laxmidas. “He had you in mind when he said that we Vaishnavas should have nothing to do with dissection of dead bodies. Father intended you for the bar!”

“I am not opposed to the medical profession as was your father. Our Shastras are not against it,” said Joshiji. “But a medical degree will not make a Dewan of you—and I want you to be Dewan, or if possible, something better. Only in that way can you take your large family under your protecting care. The times are fast changing, Moniya, and getting harder every day. It is the wisest thing, therefore, to become a barrister.” Joshiji turned to Putlibai. “Now, I must leave. Pray ponder over what I have said. When I come here next, I shall expect to hear of preparations for England. Be sure to let me know if I can assist in any way.”

“How am I to find the wherewithal to send you?” said Laxmidas, after Joshiji took his leave. “Is it even proper to trust a young man like you to go abroad alone?”

Putlibai.

“Your uncle Tulsidas is now the eldest member of the family. He should first be consulted,” said Putlibai. She was clearly uncomfortable with the idea of parting with Moniya. “If he consents, we will consider the matter.”

“We have a certain claim on the Porbandar State,” said Laxmidas. “Mr. Lely is the Administrator. He thinks highly of our family, and uncle is in his good books. It is just possible that he might recommend you for some State help for your education in England.”

Moniya liked this idea. The malady of cowardice—real or imagined—from which he long-suffered, vanished before the desire to study in England. He soon prepared for the journey to Porbandar.

~

The first leg of the trip was a five-day ride by bullock-cart to Dhoraji; from there he switched to a camel to reach his destination a day earlier. When Moniya finally arrived, he paid the customary respects to Tulsidas, and then explained the whole situation.

“I am not sure whether it is possible for one to stay in England without prejudice to one’s own religion. From all that I have heard, I have my doubts,” said Tulsidas, after careful consideration. “When I meet these big barristers, I see no difference between their life and that of Europeans. They know no scruples regarding food. Cigars are never out of their mouths. They dress as shamelessly as Englishmen. All that would not be in keeping with our family tradition. I am shortly going on a pilgrimage and have not many years left to live.” Tulsidas sighed. “Moniya, at the threshold of death, how dare I give you permission to go to England—to cross the seas?”

Moniya held his disappointment in silence.

“I will not stand in your way,” said Tulsidas. “It is your mother’s permission which really matters. If she permits you, then Godspeed! Tell her I will not interfere. You will go with my blessings.”

“I could expect nothing more from you!” said Moniya, overjoyed. “I shall now try to win over mother.”

The smile on Tulsidas’s face was apprehensive, but sincere.

“Uncle,” said Moniya, “would you not recommend me to Mr. Lely?”

“How can I do that?” said Tulsidas. “He is a good man. Ask for an appointment and tell him how you are connected. He will certainly give you one. He may even help you.”

Moniya wrote to Lely, who invited him to see him at his home. He made elaborate preparations to meet him, even carefully learning a few sentences, but it was ultimately for nothing. Moniya bowed low and saluted Lely with both hands when he called on him at his residence. “Pass your B.A. fist and then see me,” said Lely, curtly, as he ascended the staircase. “No help can be given to you now.”

Moniya returned to Rajkot and reported what transpired. He talked the matter over with Joshiji, who advised him to continue as planned, even incurring a debt if need be.

“Perhaps I might sell Kasturbai’s ornaments,” Moniya told Laxmidas. “They are worth about two or three thousand rupees.”

“I promise to find the money somehow,” said Laxmidas.

Putlibai was still unwilling to grant permission. “Someone told me that young men got lost in England,” she said. “Someone else said that they take to meat, and that they could not live there without liquor. How about all this?”

“Will you not trust me?” said Moniya. “I shall not lie to you. I swear that I shall not touch any of those things. If there were any such danger, would Joshiji let me go?”

“I can trust you,” Putlibai replied. “But how can I trust you in a distant land? I am dazed and know not what to do. I will ask Becharji Swami.”

Originally one of Moniya’s “caste people,” a Modh Bania, Becharji Swami, a family adviser like Joshiji, was now a Jain monk.

“I shall get the boy solemnly to take the three vows,” said Becharji Swami, “and then he can be allowed to go.” Becharji Swami administered the oath, and Moniya vowed to abstain from alcohol, women, and meat. Putlibai finally consented.

~

With the blessings of his elders, Moniya started for Bombay, leaving Kasturba with Harilal. Laxmidas accompanied him. When they reached Bombay, Laxmidas’s friends gave the brothers disappointing news.

“The Indian Ocean is rough in July,” they said. “As this is Moniya’s first voyage, he should not be allowed to sail until November.”

The friends also told the brothers of the steamer that sank in a Gale of the coast of L’Agulhas a few weeks earlier. It was a “coolie ship” en route to Demerara from Calcutta. The Captain was found lashed to the wheel. There were no survivors.[1]

“Moniya, I cannot take the risk of allowing you to sail immediately,” said Laxmidas.

Laxmidas, having to resume his duties in Rajkot, left Moniya in the care of his friends in Bombay. Before leaving, he gave some money to a brother-in-law for Moniya’s traveling expenses and told his friends to assist Moniya if he should need it.

The Modh Bania, meanwhile, were growing agitated with the news that Moniya was going abroad. No Modh Bania had been to England, and if Moniya dared to do so, he “ought to be brought to book!” Moniya was summoned to appear before a general meeting of his caste. The headman of the community, the Sheth, was distantly related to Moniya, and had been on very good terms with his father. Despite this relationship with his father, or perhaps because of it, the Sheth was firmly against the idea of Moniya traveling overseas.

“‘In the opinion of the caste,” said the Sheth, “your proposal to go to England is not proper. Our religion forbids voyages abroad. We have also heard that it is not possible to live there without compromising our religion. One is obliged to eat and drink with Europeans!”

“I do not think it is at all against our religion to go to England,” said Moniya. “I intend on going there for further studies. And I have already solemnly promised to my mother to abstain from the three things you fear most. I am sure the vow will keep me safe.”

“But we tell you,” said the Sheth, “that it is not possible to keep our religion there. You know my relations with your father, and you ought to listen to my advice.”

“I know those relations,” Moniya replied. “And you are as an elder to me. But I am helpless in this matter. I cannot alter my resolve to go to England. My father’s friend and adviser, who is a learned Brahman, sees no objection to my going to England, and my mother and brother have also given me their permission.”

“But will you disregard the orders of the caste?”

“I am really helpless. I think the caste should not interfere in the matter.”

The Sheth was fuming. “This boy shall be treated as an outcaste from today. Whoever helps him or goes to see him off at the dock shall be punished with a fine of one rupee four annas.”

Moniya took leave of the Sheth, unfazed by the order.

As the days passed, Moniya grew more anxious about traveling to England. “What will happen if they succeed in bringing pressure to bear on my brother?” he thought. “Suppose something unforeseen happens?” He sent news of the meeting to Laxmidas, but fortunately he remained firm in his decision, reassuring Moniya that he had his blessings to go, regardless of the Sheth’s order.

~

Moniya soon learned of a Junagadh vakil named Srijut Tryambakrai Mazmudar who, having been called to the bar, was sailing for England on September 4 on the S.S. Clyde. His friends told him that he “should not let go the opportunity of going in such company.” There was no time to lose. Moniya wired to Laxmidas for permission, which he granted. Moniya asked the brother-in-law to loan him the money for the steamer ticket, but he was refused. “I cannot afford to lose caste,” was the reply. Moniya then asked a friend of the family. “If you could accomodate me to the extent of my passage and sundries, my brother will repay you.” The friend graciously agreed. Moniya purchased a ticket for the S.S. Clyde immediately. [2]

← →

THE AGONISED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS:

INTRO: CHARLEY.

I. WITCH TALES.

II. CARELESS WHENCE COMES YOUR GOLD.

III. THE TIMES ARE CHANGED.

IV. DENIZEN OF ETERNITY.

V. DOMOVOY.

VI. WITH LOW AND NEVER LIFTED HEAD.

VII. IMPERIAL GOTHIC.

VIII. THE SERVANT OF THE QUEEN.

IX. THE DWELLER ON THE THRESHOLD.

X. INDO-GOTHIC YOGA.

XI. INTENDED FROM ABOVE.

XII. THE SÉANCE ON CHEYNE ROW.

XIII. EVEN IN NEW ROOMS.

XIV. RUSSIA’S LEGENDARY LORE.

[APPENDICES]

SOURCES:

[1] “Loss of an Emigrant Ship with All on Board.” The Kirkintilloch Herald. (Dunbartonshire, Scotland.) July 4, 1888.

[2] Gandhi, M.K. The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Navajivan Press. Ahmedabad, India. (1927): 89-104.