INTENDED FROM ABOVE

XI.

⸻

Colonel Olcott was writing, at a side table. Blavatsky was playing Patience (as she did nearly every evening.) Charley sat opposite her, talking about the East, with Colonel Olcott, who arrived the day before, on August 26, 1888.[1] From Brindisi Olcott had taken the overland route to England, (stopping briefly at the castle of Count Mattei, but Mattei was unavailable.)[2] In the brief time spent together since his arrival, Olcott’s Yankee paternalism won the affection of Charley and Verochka (both of whom he met for the first time.) [3]

Charley talked with Olcott of Subba Row’s resignation, of the Indian National Congress, and, of course, Murshidabad, where Charley would soon be stationed. A catalyst for discussion was the article about the Indian National Congress appeared in the August issue of The Westminster Review which said:

The idea of holding a Congress appears to have originated with the members of the Indian National Union, who, in the spring of 1885, issued a circular, in which Poona was selected as the place of assembly, on the ground of its central position and consequent accessibility—a point of some importance when the considerable distances were borne in mind over which many of the delegates would have to travel. The opening of the Conference was fixed for December 25, and it was announced that the delegates would be “leading politicians well acquainted with the English language,” chosen from all parts of the three Presidencies […] The Congress met in the great Hall of the Goculdas Tejpal Sanskrit College, and the proceedings were commenced by Mr. A. O. Hume.[4]

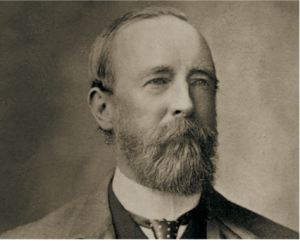

Unsurprisingly, the article failed to mention the role that Theosophy and the Masters played in the formation of the Indian National Congress. The Hume, however, mentioned in the article, was Allan Octavian Hume, a former Anglo-Indian Civil Servant who, along with his wife, Mary, joined the Theosophical Society in the summer of 1881.[5] The feats performed by Blavatsky in his home in Simla (India,) were already legendary within Theosophical circles (and infamous outside of them.)[6] Hume, a recipient of several letters from the Masters, Koot-Hoomi and Morya, was guided to make a decision which would change the course of India’s history. The Masters urged Hume to use his authority to “maintain the correct balance between East and West,” and warned him of “an impending catastrophe” that would arise should he fail to act. [7]

A.O. Hume.

1881 was an eventful year. It was the year when Olcott published the Buddhist Catechism. It was the year that the Theosophical Society began to hold their annual December Conventions.[8] These Conventions, which would prove pivotal in the Indian National Congress, brought diverse peoples of the subcontinent together to discuss Theosophy, as well as the politics, history, and hopes for India. It went a long way in forging a common identity.[9]

BENGAL

Not long after the first Convention, in March 1882, Olcott established the Berhampore Branch, in Murshidabad, which marked the official beginning of the Theosophical Society in Bengal.[10] Nobin Krishna Banerjee, a Deputy Magistrate, and Manager-General of Wards’ Estate of Murshidabad, was named the first President of the Berhampore Branch, also known as The Adhi-Boutic Bhratru T.S. (A.B.B.T.S.)

Dinanath at the the Theosophical Convention of 1883.

The Secretary of the A.B.B.T.S. was a man named Dinanath Ganguly. A distinguished scholar of the Old Hindu College, Dinanath joined the Berhampore Bar in 1854, and through his ability and advocacy, soon rose in eminence (earning the rank of Government Pleader of Berhampore and veteran Vakil and Treasurer of that city.) He joined the Theosophical Society in 1881 with Banerjee, with whom he co-founded the A.B.B.T.S.[11] Being one of the Trustees in which the stewardship of Grant Hall (the town hall of Berhampore) was vested, Dinanath secured that space for the regular weekly meetings of A.B.B.T.S.[12]

Grant Hall.

The Theosophists from the Berhampore Branch were known to visit other Branches of Bengal, acting as a central nerve of connectivity. It also had the distinction of being one of the only branches in Bengal that allowed the admittance of Hindu women to its membership. The members of Berhampore Branch were also known for assuming control of local voluntary associations, which influenced many youths in the 1880s.[13] One such example is Kali Prasanna Mukerji (one of the Secretaries of the A.B.B.T.S.) who was one of three native pastors for the London Missionary Society in Berhampore.[14] Mukerji held a position in the Court of Wards and came “highly recommended as a Bengali gentleman and a philosopher.”[15]

Dwijendranath Tagore.

By 1882, many more notable figures of India had joined the Society, including Tukaram’s old friend, Jotirao Phule, poet-philosopher, Dwijendranath Tagore, and Raghunath Row, a cousin of Mahadev Ranade.[16] Raghunath Row, a former Deputy Collector of Madras, was a “man of power,” who possessed a warm and cordial sense of humor, and whose bright blue eyes were something of a rarity among his people.[17] Claiming Śāstra-textual authority, Raghunath Row, like Blavatsky, criticized the “un-Aryan” practice of child-marriage.[18]

Of all the scholars who joined in 1882, it was T. Subba Row whom Blavatsky admired the most.[19] He first came to her attention with an article he wrote called, “The Twelve Signs of the Zodiac.”[20] By profession Subba Row was a pleader in the Madras High Court, but as to the “interior man,” Subba Row was a follower of the Hindu path known as Advaita Vedanta as expounded Adi Shankaracharya, “supreme master and sage of Southern India.” Subba Row, in fact, was the local deputy of the Sringeri Sharada Peetham (the great college of Vedanta learning in Mysore) and disciple Sacchidananda Shivabhinava Narasimha Bharati (the current Shankaracharya, of Shringeri.)[21] Subba Row’s knowledge of the Western Sciences and of Eastern Occultism was so great, that Blavatsky soon became his intimate friend, and would frequently consult him on the more difficult points of philosophy and metaphysics.[22] Though Subba Row would never speak openly of the Masters, there were many who believed that he was a disciple of Master Morya. Raghunath Row, though very much his senior (and a much-respected man,) referred to Subba Row (humorously) as “Master.”[23]

Subba Row’s father died when he was an infant. His maternal uncle (the Dewan to the Rajah of Pittapur) helped raise him. He began his English education in Coconada, later studying in Madras where he joined the Presidency College. He excelled in his studies and chose law as his profession. Rounding out his impressive skills, Subba Row was “almost the best Indian [tennis] player,” in the country. A skill developed in the English schools where the “physical culture” of “Muscular Christianity” was ingrained.[24]

“His practice became lucrative and might have been made much more so had he given less attention to philosophy,” however, as he told Olcott, “he was drawn by an irresistible attraction.” After he took his B.A. degree (with great distinction,) his mind had turned to spiritual matters. For nine years he “never could sleep,” and “he used to rack his brain night and day over spiritual subjects.” He tried some Hatha Yoga practices but claimed that relief only arrived after a visit from a mysterious “old man” who told him: “Do not go that way, but this way.” Subba Row gave no further explanation other than that the old man was a Dravidian “who had been working in this country for fifty years.”[25] Olcott praised his abilities as a conversationalist, claiming that “an afternoon’s sitting with him was as edifying as the reading of a solid book. But this mystical side of his character he showed only to kindred souls.”[26]

TANTRA.

Though Kaliprasanna (Berhampore Branch) did not join the T.S. until the summer of 1882, he was involved in the discussion of yoga initiated in The Theosophist.[27] It was Kaliprassana who initiated a wave of articles on Tantra with his discussion in “The Tantric and Puranic Ideas of Deity.” In the article Kaliprassana emphasized that the unity of all, veiled by Maya, lay at the core of that yogic, esoteric doctrine. He defined Tantra as lying at the root of all Aryan traditions, and as being separated into an esoteric and exoteric part.[28]

At the same time, Nobin K. Bannerjee (Berhampore Branch,) gave an encouraging update of the Berhampore Branch to the editors of The Theosophist. The new Nawab of Murshidabad, Hassan Ali Mirza Bahadur (whom Charley would become friends with,) donated Rs. 400 to the Library of the Branch Society. It was accompanied by a letter in which the Nawab stated that he fully sympathized with the objects of the Society, and that it was “highly desirable that every effort should be made for the regeneration of India, and the revival of its ancient glory.”[29] The news was worthy of note, for as Bannerjee said, the Nawab was “a Mahomedan Prince” while he (Bannerjee) was a Hindu Brahmin by birth. “It shows how much good can be affected,” writes Bannerjee, “if all India understands and accepts the principles of Theosophy in our efforts towards our regeneration and mutual help, even in ordinary concerns of their life, instead of giving way to animosity and antipathy based on ignorance and bigotry.”[30]

Sayyid Jamaluddin al-Afghani.

The timing of the Nawab’s praise for the T.S.’s mission of religious pluralism, came just days before the Anti-Christian riots of Alexandria, Egypt, on June 11, 1882. By July 1882 the Anglo-Egyptian War would commence. The result was the British occupation of Egypt. It was around this time (November) that the Muslim activist, Sayyid Jamaluddin al-Afghani, arrived in Calcutta, where he influenced the Muslim elite with his Pan-Islamic and anti-West ideas.[31] Al-Afghani (who claimed to be the tutor of the Mahdi,) when asked if the Mahdi could be removed by force, stated: “The best method of crushing a religious rising, to my mind, is to allow co-religionists to do it.” When asked what the word Mahdi conveyed to Muslims, al-Afghani stated: “Mahommedans believe, according to Islamic tradition, that an end of time there will appear a Mahdi, who will be recognized by certain indications, and his mission is to exalt Islam throughout the world.”[32]

ADYAR

In Mid-December 1882, at the suggestion of Subba Row and Raghunath Row, that the headquarters of the Theosophical Society relocated to a suburb of Madras called Adyar.[33] It was a time of political disruption. In February 1883 the Ilbert Bill was introduced, which proposed an amendment to the code of criminal procedure and allow Indian magistrates jurisdiction over Europeans in India.[34]

On March 27, 1883, Hassan Ali Mirza was formally installed as the first Nawab of Murshidabad in an impressive ceremony at Hazarduari Palace performed by the Lieutenant-Governor, Rivers Thompson.[35]

Hazarduari Palace.

Two weeks after the ceremony the Nawab invited Olcott (who was conducting mesmeric healings in Berhampore) to stay as his guest at the palace. Olcott agreed. On April 7th, 1883, the two highest offices in the Nawab’s “State” two men “of conspicuous merit,” arrived in Berhampore as Olcott’s escorts. They were Khondakar Fuzli Rubbee (the Nawab’s Dewan) and Janaki Nath Paure, (the first graduate of Berhampur College and “ornament to the Sanctorum of the Secretariat.”)[36] The first President of the Theosophical Society and the first Nawab of Murshidabad had a long talk that evening, in which Olcott learned more about the Nawab.[37]

THE NAWAB OF MURSHIDABAD

The Nawab of Murshidabad, Hassan Ali Mirza, was the eldest of Feradun Jah’s nineteen sons. There was a reason, however, why he did not share the title of his father, the last Nawab of Bengal. Hassan, who was known as the “Burra Sahib,” in his youth, was a quiet man, with a kind disposition and charming manners. Though Hassan was shy, he was also “amiable, steady, and anxious to learn,” and “displayed a high moral standard, and firmness,” traits which many believed were inherited from mother, Nawab Mhir Luka Begum Saheba, an Abyssinian slave-girl.[38] Being a spiritual man, Hassan never neglected his daily prayers and the Qur’an and Tasbih were placed in an honored spot above his bed. Every day he distributed betel to his people, and in the evening, he drove through Murshidabad to listen to “the wails and cries of want and poverty.” This was done so that he might better facilitate the immediately relief of his people. Hassan’s practices were “a silent, but most eloquent lesson to many.”[39] Hassan was educated by English tutors, and in 1865, when he was nineteen, he and two of his brothers, Hussain Ali Mirza “Mujlah Huzur,” and Mahomed Ali Mirza “Syed Amir Sahib,” and traveled to England with Colonel Herbert so they might “visit places of interest,” and “invite comparison between the ways of the East, and the West.” The chief reminiscences that Hassan brought away from his year in England, however, were his acquaintance with the Prince of Wales, and his instruction in billiards.[40] The princes returned to India in 1866.[41]

Feradun Jah & Sons.

At the end of the 1860s, Feradun Jah was in a difficult financial position. It was his responsibility to distribute the Government pension to his large family. He was advised by men of position in India to travel to England and make a case for more funds. In February 1869, Hassan and Feradun Jah were received at Dover by Queen Victoria’s bodyguard with honors usually reserved for independent potentates. He moved the matter into Parliament but was defeated in his attempt by a large majority of unfavorable votes.[42]

During this trip Feradun Jah met a young English woman named Sarah Venell, whom he would marry. The marriage took place in May 1870 and celebrated according to the laws of Shi’a Islam.[43] A year later Sarah had given birth to her first child, Miriam. After a stay of three years in England, Hassan left his father, and returned to Murshidabad with Fazl Rubbee, his faithful Dewan. While his father remained in England, he would administer the affairs of the Nizamat. The Muslim elites of Murshidabad at the time were embroiled in a controversy regarding the origin, and development, of the Bengali race. This was due to the publication of the Census of 1872, a report which concluded that “the foreign element amongst the Muhammedans of East Bengal is very small.” The report further suggested that Muslims of Bengal were of the same racial extraction as that of the Hindus.[44]

In 1873 the British Government assumed management of the Nizamut finances and the stipend for the Nawab Nazim. This, it was said, was “to preserve the dignity and honor of an exalted Indian family and that public sentiment may not be hurt by their fall into poverty.” By 1875 Sarah had two more children, a girl named Vaheedoonissa, a boy named Syed, and pregnant with her fourth, a boy named Nusrat. For the security of her children, as well as herself, Sarah asked the Nawab Nazim to testify to the legitimacy of their marriage before the acting Lord Mayor of London, Robert Carden. The Nawab agreed and signed an indenture affirming that Sarah was endowed £10,000 as part of the marriage contract and securing for their daughters (and any subsequent children) £5,000 from the Nizamat Fund when they reached the age of twenty-one. 1880 Feradun Jah, broken-hearted, did not wish to return to Murshidabad. He was living beyond his means, and the Government felt compelled to appoint a Commission to settle the affairs with the Nawab’s creditors. As he advanced in age, and his health declined, he expressed a desire to spend the remainder of his years in Karbala, Mesopotamia, where his ancestor, Imam Husaym was martyred. The Government, however, insisted upon either his returning to Murshidabad, or abdicate his position and privileges as the Nawab of Bengal. Feradun Jah abdicated his title and renounced all of his claims on the British Government. In agreement with the British, Feradun Jah chose Hassan to succeed him, though he, and his successors, would be known by the new title, “Nawab of Murshidabad.” In compliance for accepting his abdication, Feradun Jah received a lump sum of £83,000, and an annual stipend of £10,000. In early January 1881, Sarah’s four children moved to India to begin a new life at Hazarduari Palace. Hassan greeted them in English, and escorted to the palace of their grandmother, Gaddanashin Begum (First Lady,) and introduced them to their extended family.[45]

Hassan immediately began to formulate schemes for the management of the Nizamat affairs. There were palace intrigues, of course. Feradun Jah’s seventh son, Iskunder Ali Mirza, “Sultab Sahib,” was “on terms of rivalry,” with Hassan. Sultan Sahib’s mother was a lady of higher rank than the Hassan’s and believed that he ought to be the prospective Nawab of Murshidabad.[46]

The intrigue ultimately mattered very little.

Feradun Jah.

In mid-September 1883, a strange atmospheric phenomenon appeared in the skies over Southern India. A bright green sun, at sunrise and sunset, appeared as a “rayless globe,” at which one could easily look, and “so sharply defined that sunspots could well be seen with the naked eye.”[47] “Mahometans among them were looking for a novelty in the solar system which would assure the Faithful that the end of the world is approaching in the manner foretold.”[48]’[49] It was assumed that this event was the result of the eruption of the volcano on Krakatoa. Attention was placed on the extraordinary seismic events taking place all over the world from 1878-1883. One of the primary features of the “subterranean forces in the new earthquake period,” was the widespread nature of the phenomena. “The manner in which old volcanoes, whose chimneys had grown cold centuries earlier,” it was said, “suddenly began to first smoke and then belch forth clouds of ashes and streams of lava.” A singular phenomenon, which awakened both curiosity and alarm, was the discolored appearance presented by the sun, which in addition to its appearance in Southern India, also occurred in Venezuela.[50] A week after the appearance of the “Green Sun,” the Nawab’s brother, Mahomed Ali Mirza “Syed Amir Sahib,” died after a prolonged illness.[51] A month after that, the Nawab’s father, Feradun Jah, suffered a debilitating stroke. In response, Feradun Jah drafted a will naming Hassan, James Lyster O’Beirne (his secretary,) and Mowbray Walker (his lawyer,) as guardians of his younger children (in the event of his death.)

Feradun Jah did meet his death from cholera in October 1884. In accordance with his father’s will, Hassan sent Syed and Nusrat to England for their education, under the guardianship of Walker and O’Beirne. There, in accordance with the deed to which Sarah was a party, the two boys were raised as Muslims under the tutelage of Walker. Miriam and Vahedoonissa, who now spoke fluent Urdu, remained in Murshidabad under the guardianship of Hassan, and accepted their life in the palace compound of their grandmother.[52]

~

Subba Row.

At the Theosophical Convention of 1884, there was much talk on various topics. Subba Row spoke decisively, and his views carried great weight, but he spoke very little, and only what was necessary.[53] Raghunath Row argued that the Society should begin formally discussing the political situation in India. He subsequently arranged a meeting of sympathetic Theosophists to be held at his home to discuss the matter following the Convention.[54] All over India Theosophists were joining with other young nationalists to advance the idea of an all-India organization. A.O. Hume would soon prove a singularly important figure in the creation of the Indian National Congress.[55] The former Civil Servant received a message from the Masters. They warned him to intervene on behalf of the cause of Indian Home Rule. “The jungle is all dry,” they told him. “Fire does spread wonderfully in such when the right wind blows, and it is blowing now, and hard.”[56] Over the next several months Hume effectively convinced local Indian leaders to support plans for an Indian National Union.[57]

First Indian National Congress.

~

Olcott made a second trip to Murshidabad on July 8, 1885. He planned on meeting Nobin K. Banerji at Berhampore, but, like Feradun Jah, the President of the A.B.B.T.S. died from cholera. Hassan had developed a lively interest in the cause of Theosophy and invited Olcott to dine at Hazarduari as his guest. At the Palace, Olcott, Hassan, and one of younger brothers of the new Nawab held lengthy discussions on matters of science and religion.[58] His fourth son, Syud Asaf Ali Mirza, was born a month earlier.[59] Olcott returned to Berhampore and delivered lectures at Grant Hall and the Cantonment Theatre Hall. At the latter lecture, Olcott was introduced by J. Anderson, the Collector of Murshidabad, and Dalton’s predecessor.[60]

Nawab Syud Hassan Ali Mirza.

Less than a week after Olcott left Murshidabad, the devastating Manikganj Earthquake visited the district, damaging most of the large buildings on the Nawab’s palatial compound, and serving as a portent for things to come.[61] In early August, Sarah Begum asked the court for total custody of her four children, arguing that her marriage to the late-Nawab was invalid in accordance to English law, and therefore her children were illegitimate. It was a unique problem for the courts. English law typically granted automatic custody to the mother at this time, provided that her children were “illegitimate.” Mothers, however, held no legal rights over their children if they were born in legal wedlock. By claiming that her marriage to the late-Nawab was illegitimate, Sarah had a greater chance of gaining custody of the children. This trade off meant a forfeiture of pension provided for a widow of the Nawab of Bengal. Hassan was sympathetic, but O’Beirne and Walker refused to surrender custody of the boys.[62]

~

Olcott, meanwhile, built on the success of the Buddhist Catechism with a series called the “Catechisms of the Oriental Religions.” Srinivasa Row worked with Olcott to produce the “Dwaita Catechism.”[63] Subba Row, however, was less than enthusiastic when it came to producing Theosophical literature. Blavatsky asked Bhavani Shankar (a great friend of Subba Row) to get him to write articles for The Theosophist. Subba Row promised Bhavani to write a review of the Idyll of the White Lotus, but this failed to materialize. Bhavani paid a number of visits to Subba Row to obtain this promised review, but each and every time he was turned away with some excuse and told to come back later. Finally, during one visit, when Subba Row attempted to send Bhavani away without the article (as he had done so many times before) Bhavani told Subba Row that he was determined to sit in the house and refused to leave until he got what he had been promised. Subba Row, who was incapable of unkindness to anyone, produced a pen and paper and wrote the article straight away, “without a scratch or a correction from beginning to end.”[64]

In December 1886, Suuba Row’s discourses on the Gīțā were delivered on four mornings of the Convention.[65] Everybody admired his great capacity and power of expression, not to speak of the depth of learning displayed by him in the course of these lectures. Pandit N. Bhāshyāchārya (a Sanskrit Pandit of great ability,) was lost in admiration at the end of the lectures.[66]

It was during this Convention that the Adyar Library opened. Olcott stated during its opening ceremony, he wished to “make it a monument of ancestral learning.”[67] (Pandit N. Bhāshyāchārya, the first librarian of the Adyar Library.)[68] During the Convention, Subba Row’s observations on the sevenfold classification, and his preference for the fourfold classification touched upon in the first lecture, led to a controversy on the subject, and to H. P. B.’s replies on the matter.[69] [It was said that Subba Row’s criticism on the subject gave offence to H. P. B., who was then absent in Europe.][70] A philosophical dispute began with the publishing of a portion of Subba Row’s lecture on the Bhagavad Gita in the February 1886, issue of The Theosophist.[71] Blavatsky countered with “Classification of ‘Principles,’” an article in the April 1887 issue of the same journal. [72] Partly due to this controversy, Subba Row’s visits to the Headquarters became less frequent.[73]

The “plot at Adyar” […] began a little after the [1886 Convention]” said Blavatsky. “I received an address signed by 107 names headed by Subba Row, Cooper-Oakley [and] Nield Cook [,] begging me to return to Adyar for the next [Convention.] Then [Subba Row] came out with his attack on myself [and] the 7 principles.”[74]

“T. Subba Row was considered by [some] as more efficient in occult affairs than [Blavatsky.] Gradually the Buddha was losing His place at Adyar to Sankaracharya and his Advaitism.”[75]

~

In 1887 Hassan was created a K.C.I.E., and in May of that year the Eastern titles Ihtisham-ul-Mulk, Raes-ud-Dowla, and Amir-ul-Omrah were conferred upon him. But peace was threatened in Bengal. There was a spirit of discord in the Muslim community of Murshidabad (which had been traditionally Shia.) A “misunderstanding had arisen,” it was said, “not between Hindus and Muslims, but between the different schools of Islam.”[76] No doubt, al-Afghani had left an enduring impression.[77] At the Nawab’s request, Olcott delivered a lecture on Islam in Hazarduari Palace in June 1887. Following the lecture, Khondkar Fazl Rubbee, the Nawab’s Dewan, joined the Society (just as his colleague, Janaki Nath Pāṇi, who joined in 1886.)[78] That same month, Mowbray Walker died unexpectedly. Sarah Begum, once again, appealed for the custody of her sons. This time she had the support of both the Nawab and O’Beirne (the latter wishing to be released from the responsibility of custodianship.) The appeal was a success, and custody of the boys was awarded to Sarah.[79]

Dewan Fazl Rubbee, Khan Bhadur.

~

On the Theosophical front, Raghunath Row produced an A Simple Catechism of the Aryan Religion, from one of the “more elementary works of Sankaracharya.”[80] “In Southern India,” one newspaper said, “Mr. Ragunatha [Row,] is the only person who has come prominently forward with a serious attempt to unite the teaching of the Vedas and Puranas with the aspirations and hopes of present-day students.”[81] (At the Indian National Congress of 1887, Raghunath organized a sister movement to the called the Indian National Social Conference, whose goal it was to persuade Indians to adopt a modern, progressive stance in their moral behavior.)[82]

Subba Row was more distant. The only persons he would speak to about Occultism were C. W. Leadbeater and A. J. Cooper-Oakley (who was a sort of chela to him.)[83] Blavatsky grew suspicious of this comradery, believing that Cooper-Oakley was conspiring to prevent her returning to Adyar by “bringing forward the scare of ‘Russian spy,’ of padris,” to frighten Subba Row and drive a wedge between them.[84]

~

In early 1888, according to Kali Prasanna Mukerji, thousands of Muslims assembled in Berhampore to participate in a discussion on some articles of faith in dispute. One the one side there were Shias and Sunnis, while on the other side there were the Wahabis. Learned Muslims came from Peswar, Delhi, Jounpur, and the like, came to offer their commentary. Mukherji noted that it was a “fact not a little significant of the progress of brotherly feeling throughout India that the umpires chosen by both parties are all of them Hindus.” It was the first time in the history of India, according to Mukherji, that Hindus were chosen as “umpires,” by Hindus.[85]

In England, meanwhile, a thoroughly exhausted Blavatsky threatened to abandon her work on The Secret Doctrine. It was the belief of many Westerners that this delay stemmed from Subba Row’s perceived betrayal. In January 1888, Judge criticized the Indian Theosophists (and implicitly Subba Row) in the pages of The Path, by charging him with “Brahman narrowness in not freely communicating to European Theosophists knowledge and information he had about the Masters and kindred subjects.”[86] The letter (signed by many American Theosophists) said in part: “It is not intended to reflect upon the East Indians as a body in any way but solely to show why the signers desire that The Secret Doctrine should not be held back because some Indian pundits are against it.”[87]

On February 24, 1888, Tukaram wrote Blavatsky a letter which stated that Subba Row was now ready to help correct her Secret Doctrine, provided she omitted every reference to the Masters. This did not fare well with Blavatsky.[88] Then Tukaram sent a letter to Judge and the readers of The Path explaining the situation as it was understood in India: “These suggestions were misunderstood by some who communicated their own views on the matter to Europe, and we fear Madame Blavatsky herself has not been properly informed in what way the revision was proposed to be affected.”[89]

Around this time Subba Row, after he had played tennis with his friend, Dr. J.N. Cook (a Theosophist formerly of the London Lodge) expressed his intention of resigning his membership in the Theosophical Society. Both men, along with Cooper-Oakley, resigned a few days later.[90]

~

Following his talk with Olcott, it was agreed that Charley would attend the Convention that year as a delegate and ship out to India when Olcott returned. But Charley was now more torn than ever. He was incredibly excited to begin his adventure in India, but he was also hopelessly in love with Verochka.

There seemed no other option.

“Stay,” said Charley. “Stay, another month at least. Come with me to the seashore, it will be good for your health!”

“Staying with English will not improve me health!” scolded Verochka (knowing Charley’s mutual dislike for the English.) “They are such insensitive egoists!”[91]

“Well,” said Charley, “marry me.”

“Durak!”

“Marry me!” said Charley. “Come with me to India!”

“But you haven’t even met my family in Russia—my sisters—”

“I’ll go with you to Russia,” said Charley. “Then we can return to England to be married —just in time for both of us to leave for India.”

Tears formed in Verochka’s eyes.

“Yes.”

Everyone was very pleased with their engagement.

Arch and Bert Keightley were both convinced that the “marriage was conceived and intended from above.”[92]

“I am a terribly glad that you are coming with us,” said Olcott. “I insist that you— both of you—consider me like a second-father.” [93]

THE AGONISED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS:

INTRO: CHARLEY.

I. WITCH TALES.

II. CARELESS WHENCE COMES YOUR GOLD.

III. THE TIMES ARE CHANGED.

IV. DENIZEN OF ETERNITY.

V. DOMOVOY.

VI. WITH LOW AND NEVER LIFTED HEAD.

VII. IMPERIAL GOTHIC.

VIII. THE SERVANT OF THE QUEEN.

IX. THE DWELLER ON THE THRESHOLD.

X. INDO-GOTHIC YOGA.

XI. INTENDED FROM ABOVE.

[APPENDICES]

SOURCES:

[1] “The President’s Tour.” Supplement to The Theosophist. Vol. IX. No. 108. (September 1888): 9; Johnston, Charles. “Helena Petrovna Blavatsky: Part IV.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. VI. No. 3. (July 1900): 44-46; Johnston, Charles. “H.P.B.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXI, No. 1. (July 1931): 12-14.

[2] “The President’s Tour.” Supplement to The Theosophist. Vol. IX. No. 108. (September 1888): 9.

[3] Vera Zhelihovskaya to N.V. and E.V. Zhelihovskaya. August 15, 1888 [j.] London, England.

[4] “The Indian National Congress.” The Westminster Review. Vol. CXXX, No. 2. (August 1888): 155-173.

[5] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 829. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Allan Octavian Hume. [August 21, 1881]; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 830. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Mary Anne Hume. [August 21, 1881]

[6] Buck, Edward J. Simla: Past and Present. Thacker, Spink and Co. Calcutta, India. (1904): 115-121.

[7] Bevir, Mark. “Theosophy and the Origins of the Indian National Congress.” International Journal of Hindu Studies. Vol. VII, No. 1/3 (February 2003): 99-115.

[8] Olcott, Henry Steel. The Buddhist Catechism. Trübner & Co. London, England. (1881.)

[9] Bevir, Mark. “Theosophy and the Origins of the Indian National Congress.” International Journal of Hindu Studies. Vol. VII, No. 1/3 (February 2003): 99-115.

[10] Strube, Julian. Global Tantra. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (2022): 69-95.

[11] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 866. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Dina Nath Gangooly. [Berhampur, September 17, 1881]

[12] “Branches of The Theosophical Society—Indian.” General Report of The Thirteenth Convention of The Theosophical Society. (1889): 68-77. Majumdar, Purna Chundra. The Musnud of Murshidabad (1704-1904): Being A Synopsis of The History of Murshidabad for the Last Two Centuries. Saroda Ray. Murshidabad, India. (1905): 235; Mukhopadhyay, M. “A Short History of The Theosophical Movement in Colonial Bengal.” Paralokatattva. Kolkata: The Bengal Theosophical Society. (2017): 101-34.

[13] Mukhopadhyay, M. “A Short History of The Theosophical Movement in Colonial Bengal.” Paralokatattva. Kolkata: The Bengal Theosophical Society. (2017): 101-34.

[14] Goonewardene, C. P. “Secretaries Report for the Indian Branches.” General Report of The Thirteenth Convention of The Theosophical Society. (1889): 13-23; Walsh, J. H. Tull. A History of Murshidabad District (Bengal): With Biographies of Some of Its Noted Families. Jarrold & Sons. London, England. (1902): 70.

[15] Charles. “A Holy Man: Helping to Govern India” The Atlantic Monthly Vol. 110, No. 5. (November 1912): 653-659.]

[16] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 1080. (website file: 1A:1875-1885) Dwijendranath Tagore. (4/10/82); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 1511. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) R. Ragoonath Rao, Dewan Bahadur. (4/28/1882); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 1307. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Jotirao Govindrao Phooley. (8/14/1882.)

[17] Johnston, Charles. “The Race of The Brahmins.” The Madras Weekly Mail. (Madras, India) January 11, 1894; Johnston, Charles. “East And West: Helping to Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CIX, No. 3. (March 1912): 324-331.

[18] Blavatsky writes: “Ragunath Rao, a Brâhmana of the highest caste, who has presided for three years over The Theosophical Society of Madras, and who is at present Prime Minister (Dewan) of the Holkar, is the most fervent reformer in India. He is fighting, as so many other Theosophists, the law of widowhood, on the strength of texts from Manu and the Vedas. He has already freed several hundred young widows, destined to celibacy because of the loss of their husbands in their childhood, and he has made possible their remarriage in spite of the hue and cry of protest on the part of orthodox Brâhmanas.” Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna. Collected Writings Vol. VIII. Theosophical Publishing House. Wheaton, Illinois. (1990): 82.

[19] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 962. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Tallapragada Subba Row. (1/4/1882.)

[20] Row, T. Subba. The Philosophy of the Bhagavad-Gita: Four Lectures Delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, Held in Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 by T. Subba Row: An Appreciation. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras, India. (1921): v-xix. [T. Subba Row: An Appreciation by S. Subramaniem.]

[21] Olcott, Henry Steele. “Death of T. Subba Row, B.A., B.L.” The Theosophist, Vol. XI, No. 130 (July 1890): 576-578.

[22] Row, T. Subba. Lectures on the Study of the Bhagavat Gita: Being a Help to Students of Its Philosophy. The Bombay Theosophical Publication Fund. Bombay, India. (1897): iii-vi.

[23] Row, T. Subba. The Philosophy of the Bhagavad-Gita: Four Lectures Delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, Held in Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 by T. Subba Row: An Appreciation. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras, India. (1921): v-xix. [T. Subba Row: An Appreciation by S. Subramaniem.]

[24] Row, T. Subba. The Philosophy of the Bhagavad-Gita: Four Lectures Delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, Held in Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 by T. Subba Row: An Appreciation. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras, India. (1921): v-xix. [T. Subba Row: An Appreciation by S. Subramaniem.]

[25] Row, T. Subba. The Philosophy of the Bhagavad-Gita: Four Lectures Delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, Held in Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 by T. Subba Row: An Appreciation. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras, India. (1921): v-xix. [T. Subba Row: An Appreciation by S. Subramaniem.]

[26] Olcott writes: “It was as though a storehouse of occult experience, long forgotten, had been suddenly opened to him; recollection of his last preceding birth came in upon him; he recognized his Guru, and thenceforward held intercourse with him and other Mahatmas; with some, personally at our Headquarters with others elsewhere and by correspondence.” [Olcott, Henry Steele. “Death of T. Subba Row, B.A., B.L.” The Theosophist, Vol. XI, No. 130 (July 1890): 576-578.]

[27] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 1341. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Kali Prasanna Mukherji. (09/18/1882); Johnston, Charles. “A Holy Man: Helping to Govern India” The Atlantic Monthly Vol. 110, No. 5. (November 1912): 653-659; Strube, Julian. Global Tantra. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (2022): 110. [69-112.]

[28] Kaliprasanna writes: “The doctrines laid in the ‘Gnyan Kanda’ are called secret doctrines and are supposed to be known and understood by ‘Yogees’ and ‘Paramahansas’ only. They appear unanimously to agree in considering that the universe is not anything separate, created by God, but simply a manifestation of the ‘Infinite’ in different shapes and forms perceived by the senses only through ‘Maya,’ illusion or ignorance, to which they attribute the cause of the phenomenal world. This ‘Maya’ is called the Primitive Force, the ‘Adi Sakti,’ ‘Prakriti,’ the ‘Adi Nilri,’ or the first mother, and is supposed to be the first emanation from the Infinite giving birth to the three deities, ‘Brahma,’ ‘Vishnu,’ and ‘Shiva,’ the supposed principles and causes of creation, preservation, and dissolution. Shiva, although produced from the first force, and represented as ‘Kal’ (time), or ‘Mahakal’ (eternity,) is supposed to be again the husband of ‘Adi Nari’ cooperating with her in first giving rise to the world, and then absorbing everything into themselves. He is without beginning, and his end is not known, and from him the revolutions of creation, continuance, and dissolution unintermittingly succeed. The object of constant meditation of Shiva is ‘Byom,’ Akash (ether.)” [Mookerji, Kali Prasanna. “The Tantric and Puranic Ideas of Deity.” The Theosophist. Vol. III, No. 33. (June 1882): 226-227.]

[29] The Nawab writes: “[The Palace, Murshidabad, June 3, 1882.] Dear Sir, I have received your letter of [May 26,] informing me that a Branch Theosophical Society has been established at Berhampore, and a Library in connection therewith. I fully sympathize with the objects of the Society, and feel it a pleasure to contribute, in furtherance thereof, the sum of Rs. 400. It is highly desirable that every effort should be made for the regeneration of India, and the revival of its ancient glory; and I wish you every success in your noble undertaking. Yours truly, Hussan Ali Mirza.] “A Nawab’s Gift.” Supplement to The Theosophist. Vol. III. No. 34. (July 1882): 4.

[30] “A Nawab’s Gift.” Supplement to The Theosophist. Vol. III. No. 34. (July 1882): 4.

[31] De, Amalendu. “The Social Thoughts and Consciousness of The Bengali Muslims In The Colonial Period.” Social Scientist. Vol. XXIII, No. 4/6 (April-June 1995): 16- 37.

[32] “A Master in Islam on the Present Crisis.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) April 11, 1885.

[33] “Editorial Notes.” The Indian Daily News. (Calcutta, West Bengal) December 26, 1882; Khandalavala, N. D. “Madame H.P. Blavatsky as I Knew Her.” The Theosophist. Vol. L, No. 9. (June 1929): 213-222.

[34] Hirschman, Edwin. “White Mutiny”: The Ilbert Bill Crisis in India and Genesis of the Indian National Congress. Heritage. Delhi, India. (1980): vi.

[35] “Installation of the Nawab of Moorshedabad.” The Indian Daily News. (West Bengal, India.) April 3, 1883.

[36] Majumdar, Purna Chundra. The Musnud of Murshidabad (1704-1904): Being A Synopsis of The History of Murshidabad for The Last Two Centuries. Saroda Ray. Murshidabad, India. (1905): 62; Charabarty, Rajarshi. “Murshidabad District Region: Transition from Pre-Colonial to Colonial Education System.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 2017. Vol. LXXVIII. (2017): 700-707.

[37] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume II. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1900): 418-419.

[38] Walsh, J.H. Tull. A History of Murshidabad District (Bengal): With Biographies of Some of Its Noted Families. Jarrold & Sons. London, England. (1902): 203-205.

[39] Majumdar, Purna Chundra. The Musnud of Murshidabad (1704-1904): Being A Synopsis of The History of Murshidabad for the Last Two Centuries. Saroda Ray. Murshidabad, India. (1905): 55-62.

[40] Cox, Edmund C. My Thirty Years in India. Mills & Boon. Limited. London, England. (1909): 36.

[41] “The Late Nawab of Murshidabad.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (Calcutta, India.) January 3, 1907.

[42] “The Nawab Nazim and His Claims.” Illustrated Berwick Journal. (Berwick, England) March 4, 1870; “The Late Nawab Nazim of Bengal.” The Indian Statesman. (Calcutta, India.) December 9, 1884.

[43] “The Extraordinary Anglo-Indian Marriage Case.” The Salisbury Times and South Wilts Gazette. (Salisbury, England.) August 15, 1885.

[44] De, Amalendu. “The Social Thoughts and Consciousness of The Bengali Muslims in The Colonial Period.” Social Scientist. Vol. XXIII, No. 4/6 (April-June 1995): 16- 37.

[45], Innes Lyn. The Last Prince of Bengal. The Westbourne Press. London, England. (2021): 75-134.

[46] Walsh, J.H. Tull. A History of Murshidabad District (Bengal): With Biographies of Some of Its Noted Families. Jarrold & Sons. London, England. (1902): 201; Cox, Edmund C. My Thirty Years in India. Mills & Boon. Limited. London, England. (1909): 40.

[47] “‘Red’ And ‘Green’ Suns.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts.) December 15, 1883.

[48] “Wednesday Evening, September 26.” The Evening Standard.” (London, England) September 26, 1883.

[49] Olcott writes: “The autumn of 1883 and the succeeding few months were noteworthy for the occurrence of brilliant phenomena in the western sky in every part of the globe, but especially in the Indian ocean and the South Pacific. Shortly after sunset a vivid red glow suffused the entire western sky, remaining for upwards of an hour, when it would slowly fade away. This strange sight was first noticed in India, where, it is said, the sun assumed a distinct greenish tinge on nearing the horizon. In the latitudes of N. Am. these red sunsets were of almost nightly occurrence for several months. All of us at Adyar can bear testimony to the greenish afterglow and to its great beauty as a new element in the color scheme. The delicacy of the tint was indescribable, it was, as it were, a sublimation of the hue of the emerald, such as one finds in rising to supramundane planes.” [Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume VI. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras. India. (1935): 196.]

[50] “Recent Terrestrial Convulsions.” The Sun. (New York, New York) October 19, 1883.

[51] “Obituary.” The Times of India. (Bombay, India) September 28, 1883.

[52] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume II. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1900): 418-419.

[53] Row, T. Subba. The Philosophy of the Bhagavad-Gita: Four Lectures Delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, Held in Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 by T. Subba Row: An Appreciation. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras, India. (1921): v-xix. [T. Subba Row: An Appreciation by S. Subramaniem.]

[54] Kumar, Kedar Nath. Political Parties in India, Their Ideology and Organization. Mittal Publications. New Delhi, India. (1990): 66; Chintamani, Chirravoori Yajneswara. Indian Social Reform: Being A Collection of Essays, Addresses, Speeches. Minerva Press. Madras, India. (1901): 364-365; Aiyar, B. V. Kamesvara. Sir A. Sashiah Sastri, K. C. S. I.: An Indian Statesman; A Biographical Sketch. Srinivasa, Varadachari & Co. Madras, India. (1902): 149; Bayly, Susan. The New Cambridge History of India: Caste, Society and Politics in India from The Eighteenth Century To The Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, England. (1999): 155-156; Pennington, Brian K. Was Hinduism Invented? Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (2005): 7-9.

[55] Bevir, Mark. “Theosophy and the Origins of the Indian National Congress.” International Journal of Hindu Studies. Vol. VII, No. 1/3 (February 2003): 99-115.

[56] Wedderburn, William. Allan Octavian Hume, C.B.; Father of the Indian National Congress, 1829 to 1912. T. Fisher Unwin. London, England. (1912): 79-80.

[57] Bevir, Mark. “Theosophy and the Origins of the Indian National Congress.” International Journal of Hindu Studies. Vol. VII, No. 1/3 (February 2003): 99-115.

[58] “2nd September.” The Madras Weekly Mail. (Tamil Nadu, India) September 5, 1885; “News From The Branches.” Supplement To The Theosophist. (September 1885): 311-314; Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Vol. III (1883-1887.) The Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1904): 274-275.

[59] Walsh, J.H. Tull. A History of Murshidabad District (Bengal): With Biographies of Some of Its Noted Families. Jarrold & Sons. London, England. (1902): 205.

[60] “The ’Calcutta Gazette.’” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (London, England.) November 29, 1887.

[61] Al Zaman, Abdullah; Monira, Nusrath Jahan. “A Study of Earthquakes in Bangladesh and the Data Analysis of the Earthquakes That Were Generated in Bangladesh and its’ Very Close Regions For The Last Forty Years (1976-2016.)” Journal Of Geology & Geophysics. Vol. VI, No. 4. (2017); “The Earthquake in Lower Bengal.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (Calcutta, India.) July 25, 1885.

[62] “The Extraordinary Anglo-Indian Marriage Case.” The Salisbury Times and South Wilts Gazette. (Salisbury, England.) August 15, 1885; Innes, Lyn. The Last Prince of Bengal. The Westbourne Press. London, England. (2021): 75-134.

[63] Olcott writes: “Our friend Judge P. Sreenivasa Row…drafted for me the ‘Dwaita Catechism,’ for my proposed series of elementary handbooks of the ancient religions, and at this time [1886] I received from him the MS and edited it for publication.” Olcott, H.S. “Old Diary Leaves.” The Theosophist. Vol. XX, No. 7. (April 1899): 385-392; Olcott, Henry S., Row, P. Sreenevsa. The Hindu Dwaita Philosophy of Sriman Madhwacharyar. The Minerva Press. Madras, India. (1886): Prospectus, Preface.

[64] Row, T. Subba. The Philosophy of the Bhagavad-Gita: Four Lectures Delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, Held in Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 by T. Subba Row: An Appreciation. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras, India. (1921): v-xix. [T. Subba Row: An Appreciation by S. Subramaniem]; Row, T. Subba “The Idyll of the White Lotus [An Explanation.] Pt. I.” The Theosophist. Vol. VII, No. 82 (July 1886): 656-660; Row, T. Subba “The Idyll of the White Lotus [An Explanation.] Pt. II.” The Theosophist. Vol. VII, No. 83 (August 1886): 705-708.

[65] Row, T. Subba. Lectures on the Study of the Bhagavat Gita: Being a Help to Students of Its Philosophy. The Bombay Theosophical Publication Fund. Bombay, India. (1897): 197; Row, T. Subba. The Philosophy of the Bhagavad-Gita: Four Lectures Delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, Held in Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 by T. Subba Row: An Appreciation. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras, India. (1921): v-xix. [T. Subba Row: An Appreciation by S. Subramaniem.]

[66] Row, T. Subba. The Philosophy of the Bhagavad-Gita: Four Lectures Delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, Held in Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 by T. Subba Row: An Appreciation. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras, India. (1921): v-xix. [T. Subba Row: An Appreciation by S. Subramaniem.]

[67] “The Theosophical Society: Opening of The Oriental Library.” The Madras Weekly Mail. (Madras, India) January 5, 1887.

[68] Bhāshyāchārya, N. The Age of Patanjali. The Theosophist Office. Adyar, India. (1905): Title Page.

[69] Row, T. Subba. The Philosophy of the Bhagavad-Gita: Four Lectures Delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, Held in Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 by T. Subba Row: An Appreciation. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras, India. (1921): v-xix. [T. Subba Row: An Appreciation by S. Subramaniem.]

[70] Row, T. Subba. The Philosophy of the Bhagavad-Gita: Four Lectures Delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, Held in Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 by T. Subba Row: An Appreciation. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras, India. (1921): v-xix. [T. Subba Row: An Appreciation by S. Subramaniem.]

[71] Row, T. Subba “Bhagavad Gita” The Theosophist. Vol. VII, No. 77 (February 1886): 281-285.

[72] Blavatsky, H.P. “Classification Of ‘Principles.’” The Theosophist. Vol. VIII, No. 91 (April 1887): 448-456.

[73] Row, T. Subba. The Philosophy of the Bhagavad-Gita: Four Lectures Delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, Held in Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 by T. Subba Row: An Appreciation. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras, India. (1921): v-xix. [T. Subba Row: An Appreciation by S. Subramaniem.]

[74] Gomes, Michael. “The Letters of H.P. Blavatsky to W.Q. Judge: Part V: Letter Dated Sept. 15, 1887, and Part VI: Letter Dated Sept. 27, 1887” Theosophical History. Vol. V, No. 6 (April 1995): 204-207.

[75] Dhammapala, Bhikku Devamitta. “Reminiscences of My Early Life.” The Maha Bodhi Centenary Volume 1891-1991. [Vol. XCVIII, Nos. 7-12 (1990) & Vol. XCIX. Nos. 1-12 (1991.)]: 66-71.

[76] “A Spirit of Toleration.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (London, England) July 28, 1891.

[77] De, Amalendu. “The Social Thoughts and Consciousness of The Bengali Muslims In The Colonial Period.” Social Scientist. Vol. XXIII, No. 4/6 (April-June 1995): 16- 37.

[78] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume III 1883-1887. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1904): 438; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4026 (website file: 1B/30) Fuzli Rubeee Nawab Dewan; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 2615. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Janaki Nath Panni.

[79] Innes, Lyn. The Last Prince of Bengal. The Westbourne Press. London, England. (2021): 75-134.

[80] “The Aryan Catechism.” The Theosophist. Vol. IX, No. 98. (November 1887): 132.

[81] Gulliford, H. “Dewan Ragunatha Rau as a Religious Reformer.” The Madras Weekly Mail. (London, England) October 31, 1888.

[82] “Indian Intelligence.” The Indian Magazine. No. 208 (April 1888): 220-224.

[83] Row, T. Subba. The Philosophy of the Bhagavad-Gita: Four Lectures Delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, Held in Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 by T. Subba Row: An Appreciation. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras, India. (1921): v-xix. [T. Subba Row: An Appreciation by S. Subramaniem.]

[84] “Blavatsky writes: “[Cooper-Oakley and Subba Row] intrigue to prevent my returning to Adyar, bringing forward the scare of ‘Russian spy,” of padris etc. They write letters (not [Subba Row]) incessantly that Master is against me & directs [Subba Row] (!) how to palliate the evil I have done!! That the L.L. here is positively lost, having fallen under my evil influence & being psychologized by me. Olcott, as you see writes that the Counsel has passed a unanimous resolution to ask me to postpone my return. I knew all this; I knew the meaning of Nield Cook’s sentence: Subba Row is the only one to save the Society (founded by me!!) & he is preparing a great Reform. Poor fools! Well, I have raised a ‘Frankenstein’ & he seeks to devour me. You alone can save the fiend & make of him a man. Breathe into him a Soul if not the Spirit. Be his Saviors in the U.S. & may the blessings of my Superiors & yours descend on you.” Gomes, Michael. “The Letters of H.P. Blavatsky to W.Q. Judge: Part V: Letter Dated Sept. 15, 1887, and Part VI: Letter Dated Sept. 27, 1887” Theosophical History. Vol. V, No. 6 (April 1995): 204-207.

[85] Mukerji, K.P. “Religious Arbitration.” The Theosophist. Vol. IX, No. 102 (March 1888): 378.

[86] Row, T. Subba. The Philosophy of the Bhagavad-Gita: Four Lectures Delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, Held in Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 by T. Subba Row: An Appreciation. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras, India. (1921): v-xix. [T. Subba Row: An Appreciation by S. Subramaniem.]

[87] “January 10, 1888. Madame H.P. Blavatsky, Respected Chief:—We have just heard that you have been asked to withdraw from publication the Secret Doctrine. This extraordinary request emanates, we are told, from members of the Theosophical Society, who say that if the book is brought out it will be attacked or ridiculed by some East Indian pundits, and that it is not wise to antagonize these Indian gentlemen. We most earnestly ask you not to pay heed to this desire, but to bring out the Secret Doctrine at the earliest possible day. It is a work for which we, and hundreds of others all over the United States, have been waiting for some years, most of us standing firmly on the promise made by yourself that it was being prepared and would appear. While the West has the highest regard for the East Indian philosophy, it is, at the same time, better able to grasp and understand works that are written by those acquainted with the West, with its language, with its usages and idiom, and with its history, and who are themselves westerns. As we well know that it is from the West the chief strength of the Theosophical Society is to come, although its knowledge and inspiration may and do reach us from the East, we are additionally anxious that you, who have devoted your life to this cause and have hitherto granted us the great boon found in Isis Unveiled, should not now stop almost at the very point of giving us the Secret Doctrine, but go on with it in order that we may see your pledge fulfilled and another important stone laid in the Theosophical edifice. Further, we hasten to assure you that it makes but small difference–if any whatever–here in the vast and populous West what anyone or many pundits in India say or threaten to say about the Secret Doctrine, since we believe that although a great inheritance has been placed before the East Indians by their ancestors they have not seized it, nor have they in these later days given it out to their fellow men living beyond the bounds of India, and since this apathy of theirs, combined with their avowed belief that all Western people, being low-caste men, cannot receive the Sacred Knowledge, has removed these pundits from the field of influence upon Western thought. And lastly, knowing that the great wheel of time has turned itself once more so that the Powers above see that the hour has come when to all people, East and West alike, shall be given the true knowledge, be it Vedantic or otherwise, we believe that the Masters behind the Theosophical Society and whom you serve, desire that such books as the Secret Doctrine should be written. We therefore earnestly entreat you not to be moved from your original purpose and plain pledge that, before passing away from our earthly sight, you would lay before us the Secret Doctrine. Receive, Madame, the assurances of our high esteem and the pledge of our continued loyalty.” [“Correspondence.” The Path. Vol. II, No. 11 (February 1888): 354-355.]

[88] Murphet, Howard. When Daylight Comes. The Theosophical Publishing House. Wheaton, Illinois. (1975): 228; Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna.; de Zirkoff, Boris (ed.) The Secret Doctrine. Quest Books. Wheaton, Illinois. (1993): 47.

[89] Tukaram’s letter read: “It seems to us that the letter has been based upon information which is not correct. Had Madame Blavatsky been in India, the book would long ago have seen the light. Owing, however, to her stay in Europe, it has not been found so very easy to have the great work revised, as had been originally proposed. Parts of the work were sent to this country, when some good suggestions were made with a view to enhance the value of the book by making it more exact in its allusions to Hindu literature. These suggestions were misunderstood by some who communicated their own views on the matter to Europe, and we fear Madame Blavatsky herself has not been properly informed in what way the revision was proposed to be affected […] There is no opposition here against the publication of the mysteries of occultism. A few sympathetic friends can easily arrange to have the work revised, if the false impressions produced by unfounded reports were forgotten and the work placed in the hands of those who are capable of revising it.” (The letter was signed by Tukaram, Rustomji, N.D. Khandalavala, K.M. Shroff among others.) [“Correspondence: The Secret Doctrine” The Path. Vol. III, No. 4 (June 1888): 97-99.]

[90] “Resignations.” The Supplement To The Theosophist. Vol. IX. (June 1888): xlii; Row, T. Subba. The Philosophy of the Bhagavad-Gita: Four Lectures Delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, Held in Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 by T. Subba Row: An Appreciation. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Madras, India. (1921): v-xix. [T. Subba Row: An Appreciation by S. Subramaniem.]

[91] Vera Petrovna writes: “V[era] scolded him, saying that only the English (and he hates them!)” [Vera Zhelihovskaya to N.V. and E.V. Zhelihovskaya. August 15, 1888 [j.] London, England.]

[92] Vera Zhelihovskaya to N.V. and E.V. Zhelihovskaya. August 15, 1888 [j.] London, England.

[93] Vera Zhelihovskaya to N.V. and E.V. Zhelihovskaya. August 15, 1888 [j.] London, England.