CHARLEY.

The protagonist of our story, Charles Johnston, or “Charley” as he was known to friends, was born in Ballykilbeg, County Down, February 17, 1867. “The son of an Irish landlord,” as he would say, “early indoctrinated with the strictest principles of imperialism and Protestant ascendancy, and at the same time an enthusiastic student of Irish national history, literature, culture, and tradition.” His studies of Irish history began under “the domination of his stern father, well known in the House of Commons as Mr. Johnston of Ballykilbeg who was a vigorous opponent of the Irish Parliamentary Party.”

BALLYKILBEG.

He was the third child of the famous “Orangeman,” William Johnston, a Conservative-Unionist M.P. for South Belfast, and Georgiana Barbara Hay. His older siblings were his sister, Georgiana “Georgie” (b. 1864,) and his brother Lewis (b. 1865,) while his younger siblings were his brother, William (b. 1876,) and his sister, Ada (b. 1873.)

Derby School.

For three years, beginning in 1878 Charley and Lewis attended boarding school at Derby School, in Derbyshire, England. In 1881 they returned home to Ireland. “Few things endeared me to my motherland,” Charley writes, “as the need of leaving it, to go to a school across the Channel, and the joy of returning thrice a year.” Charley would live variously in Belfast, Ballykilbeg, and Dublin.

~

In Dublin, Charley enrolled at Erasmus Smith High School at 40 Harcourt Street, one of the few large high schools in the city. The school was less than a decade old when Charley registered for classes, but the building, the former mansion of the late Jonathon Swift, had a much older history; the torch extinguishers of the author of Gulliver’s Travels could still be seen on either side of the doorway. Soon after his enrollment, Charley met another new student, a “lanky youth, with shaggy black hair,” named William Butler Yeats. The two boys would become fast friends. “Some instinct drew us together,” Yeats would later say. “Willie Yeats and I gravitated together,” Charley would confirm. They bonded over a shared interest in science, and enjoyed experimenting “in physics, chemistry, and electricity, with some homemade contrivances,” to varying degrees of success. “[Yeats] was a rabid Darwinian,” Charley would say, “and, like all new proselytes, longed for a convert; and I, as his school chum, was the natural prey.”

Charley was more sympathetic of spiritual matters. “In the midst of a civilization where so much is worldly, selfish, materialistic,” Charley would say of the Irish people, “there would seem to be an evident mission for the children of a race so full of mysticism, with so long a spiritual heredity, so tempered by suffering and sacrifice.” Though Yeats was consistently at the bottom of the class, he “hated fools,” and admired Charley, who consistently “beat all of Ireland in the Intermediate Examinations,” and whose name and accomplishments appeared, every year, on the tablets on the walls of the High School. Charley once boasted to Yeats: “There is nothing I cannot learn, and there is nothing that I want to learn.”

~

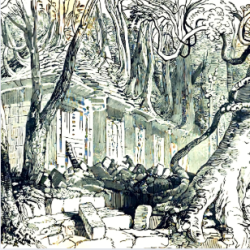

Financial troubles forced the Yeats family move to Howth, a suburb of Dublin, in the Spring of 1882. Charley would take a train out there to meet him, and they would spend their days exploring the environs of town. The investigated the immense cromlech at the foot of Howth Castle, one of the “most awe-inspiring and mysterious monuments in the world,” Charley would write, “huge silent relics, so old that even legends concerning them have vanished utterly.”

Howth, Ireland.

The people of Howth called this cromlech ”Finn’s Quoit,” because an ancient legends said the rocks were thrown there by the Irish hero, Fionn mac Cumhaill, during one of his battles. The Irish poet, Samuel Ferguson, a literary inspiration to Yeats, had composed a masterpiece of late nineteenth-century romanticism inspired by this site, The Cromlech On Howth (1861.) As stated in The Cromlech On Howth, “The great green rath,” held the promise of lost treasures, and so Charley and Yeats dug for a lost “treasure-chamber” in a ráth.

Less than a decade earlier Heinrich Schliemann rediscovered the city of Troy, so the plan was not entirely far-fetched. Charley would later write: “[There were] a series of successive civilizations, each destroyed by a natural cataclysm, and separated from its successor by enormous spaces of time; one city being built upon the buried ruins of another, as Schliemann discovered in his excavations at Troy.” Charley and Yeats did not share Schliemann’s luck in retrieving evidence which would elevate the legends from “pure myth.” They consoled themselves by exploring a nearby rock-hewn Danaan Druid chamber that overlooked the sea.

“Ireland’s Eye.”

There is a story of this time of how Charley and Yeats went to explore the nearby islands of Lambay and Ereann-Ey (Ireland’s Eye,) that latter of which got its name from the Danish word Ey, meaning Island. Ireland’s Eye was long-associated with the early religious history of Ireland. St. Nessan founded a chapel there in the middle of the sixth century. The boys took a small boat for the islands, where, upon arrival, they drew up their vessel “incautiously among the seaweed mantled rocks.” They spent a good portion of the day watching the seagulls, being a great lover of nature and science, Charley was especially interested in ornithology, and was known to “note every shade of color of the beautiful [seagulls.]” They rest of the day they explored the cliffs, and what remained of St. Nessan’s Church.

In the evening Charley and Yeats returned to their boat, only to discover that the outgoing tide had left their craft high and dry and “immoveable.” Charley and Yeats kept their bearings. As darkness fell, Yeats produced a set of chess pieces and a board from his pocket, and they passed their time playing a game of chess. When the air grew colder, they abandoned their game, and took a walk along the surf in an effort to keep warm. “Losing themselves in ‘never-failing conversation,’” they distracted themselves by discussing “the rippling luminous creatures of the sea.” In the midst of their discussion they could hear the faint sound of someone calling out their names. They shouted back a “halloo.” It was J. B. Yeats, who arrived home earlier that day only to discover that Yeats and Charley “were missing somewhere on the water in a rowboat.”

When it was almost dark, and the boys were still missing for hours, the elder Yeats insisted on rowing out to Ireland’s Eye with a local fisherman, who was “too polite” to tell him “that the boys were hopelessly lost.” J. B. Yeats, himself, had nearly given up hope on finding them. “I think I had an abiding belief,” J. B. Yeats confessed, “that both of these generous boys had lucky stars.” They were “without topcoats and without food and consequently very hungry and very cold,” yet neither seemed particularly worried. Charley simply asked the elder Yeats whether he would still be able to catch his train back to Dublin. J.B. Yeats was impressed by their stoicism, “which he thought one of the characteristics of genius.”

William Butler Yeats.

The period when science became humanized and “touched with culture,” came to Yeats under the tutelage of J.B. Yeats. “Many of the finer qualities of Yeats’ mind were formed in the studio on St. Stephen’s Green,” Charley writes, “in long talks on art and life, on man and God, with his sensitive, enthusiastic father. “

~

Reclaiming of Irish history, and Ireland’s connection to the mysterious “Aryans,” were topics being discussed during the time in which the Charley and Yeats explored the cromlechs. Throughout April and May 1882, Robert Atkinson, Professor of Sanskrit at Trinity College, was delivering a series of lectures to raise funds for the construction of a permanent home for Dublin Zoo’s newest acquisition, two young Burmese elephants named Rama and Sita. Atkinson’s talk, “The Origin Of The Kelts,” would explore the cultural branches of the Indo-European people through ethno-linguistics. In the 1890s Charley would write:

A few years ago, the “Aryans” enjoyed an unrivaled popularity, in every work on philology, or philosophy, or anthropology which had any pretensions at all to reflect the latest wisdom of the times. We were met on every page by eulogies on the superiority of the “Aryans,” their high culture, unrivaled civilization and inherent rights to dominate all “non-Aryan” peoples. We were even told, in all seriousness, that the “Aryan” brain was not only of greater specific capacity than the cephalic content of the “non-Aryan,” but that it further possessed the wonderful capacity of continuing to expand at an age when the “non-Aryan” brain had ceased to grow for several years.

As the topic of the “Aryan” deserves a more thorough explanation, we will return to it in the following installment of this series. It is mentioned here to contextualize the next phase of Charley’s life, one in which we find him engaging with philological and metaphysical subjects.

Rama & Sita.

Yeats and Charley then immersed themselves “with the Wisdom of India,” and conducted experiments in the Kildare Street Museum, using Baron Reichenbach’s theories on “Odic Force” as a blueprint. Then came experiments which involved finding “pins blindfolded,” and reading the manuals published by the Theosophical Society.

Finding “pins blindfolded” was the purview of Stuart Cumberland, the “muscle-reading” paranormal skeptic, who believed in the power of suggestion. Here we must take a detour and check-in on the happenings of the Theosophical movement, and introduce a few more “characters” which will factor into both Charley and Yeats’s life in subsequent years.

~

In May 1884 Cumberland conducted an experiment in the offices of the The Pall Mall Gazette, a London newspaper. Among those in attendance were the Irish poet and playwright, Oscar Wilde, the American industrialist-philanthropist, Andrew Carnegie, the President of the Theosophical Society, Colonel Henry Steel Olcott, the Russian political writer, Olga Novikova, and investigative journalist and editor for The Pall Mall Gazette, William T. Stead.

Novikova, “charmed by [Blavatsky’s] powerful intellect,” became a believer, and joined the Theosophical Society five months earlier. Her friendship with Blavatsky would begin shortly after the “sitting” with Cumberland. Her friendship with Stead was older. In the 1870s Novikova published articles promoting an Anglo-Russian alliance with the assistance of Stead. Despite the fact that both Novikova and Stead were married, they entered into an affair. Stead’s wife discovered the liaison, and the marriage was preserved when Stead promised to end the relationship. “I am still deeply attached to [Novikova,] but I no longer love her with that sinful passion the memory of which covers me with loathing, remorse and humiliation,” Stead would say, “I love her intensely, but no longer as a second wife.”

(Back) Stuart Cumberland. (Front, Left to Right) Olga Novikova, W.T. Stead, Oscar Wilde, Andrew Carnegie, Col. H.S. Olcott.

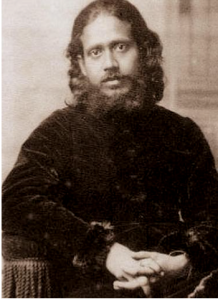

Colonel Olcott was in Europe with co-founder of the Theosophical Society, the Russian mystic, Madame Helen Blavatsky, along with Assistant Secretary to the Bengali Branch, Mohini Chatterji, a lawyer and scholar. At the time of the “sitting” for Cumberland’s muscle-reading experiment, a fissura developed in the London Lodge of the Theosophical Society, resulting in its president, Anna Kingsford, to establish a new organization, The Hermetic Society.

Blavatsky would make a brief return to India late in 1884, but would spend the remainder of her life in various parts of Europe, battling illness and writing her magnum opus, The Secret Doctrine. Olcott would return to India, and make frequent trips, regional and otherwise, for the benefit of the Society.

~

In the fall of 1884 Yeats learned of A.P. Sinnett’s book, The Occult World, at a soiree held by Edward Dowden. Yeats subsequently gave it to Charley who found the descriptions of “occult phenomena […] wholly credible.” Charley, though still a youth at 17-years-of-age, was expected to make a decision regarding his future vocation. He corresponded with at least one Missionary Society, asking to be sent to the South Seas. He was torn between a desire to enter the Indian Civil Service, and the desire to honor his father’s wish, and become ordained in the Church of Ireland. In a letter to William Johnston in late-January, 1885, Charley writes: “I find I can’t can’t go in for the Indian Civil Service, as it certainly comes under the head ‘Treasures upon Earth…’ I am not quite sure yet whether I should read for the Irish Church, or join the Colonial and Continental Society.” The pressure to choose a path was heightened a month later when the Johnstons welcomed a new member to their family, a little sister named Ina Johnston, who was born on February 26, 1885.

Kildare Street Library, Dublin, Ireland.

Yeats, at this time, offered to lend to Charley two books he had recently read, Ernest Rénan’s, The Life of Jesus, and A.P. Sinnett’s, Esoteric Buddhism. Charley declined both. Days later, however, in an idle moment while reading for an examination in Kildare Street Library, Charley asked Yeats to borrow Esoteric Buddhism. It was just before Easter (April 5, 1885,) and the full significance of the subject “came home” to him. Charley was entirely convinced of the truth of Blavatsky’s message, “of the reality of the Masters, and of her position as Messenger of the Great Lodge.” Charley wrote to the missionaries, withdrawing his letter, and pledged himself to the Theosophical Society as a chela.”

Two weeks after Easter, on April 21, 1885, William Johnston seconded a resolution regarding the general state of the Church of Ireland that called for a vindication of the character of that Protestant institution. The remarks were considered too provocative for a government official, and he was subsequently dismissed from his position as Inspector of the Fisheries. This would further add to the immediacy of the career choice which Charley would have to make.

In 1885 Yeats and Charley formed The Dublin Hermetic Society (D.H.S.,) named after Anna Kingsford’s analogous society in London. The Society held its inaugural meeting on June 16, 1885, at Trinity College. Yeats delivered an address about the objects of the Society, and Charley read a paper on Esoteric Buddhism. Thomas W. Rolleston, editor of the Dublin University Review, in sympathy with the D. H. S. published both the announcement of the Hermetic Society, and Charley’s paper, Esoteric Buddhism. “This philosophy is no new thing,” Charley writes. “Those who know say it is all to be found in the Bhagavad Gita, though clothed in mystic symbology.”

William Johnston, ousted from work, sought relief from his creditors by expressing an interest in a colonial governorship. Though Johnston was unwavering in his support of the Crown, it was straightened finances, rather than a commitment to Empire, which, like many landed Unionists, dictated his career path. Some of the impulses which propelled Irish gentlemen into colonial service, poverty for example, informed the decision of these Unionists. It was in this connection that William Johnston traveled to London in the summer of 1885, bringing with him his two sons, Lewis and Charley.

On June 20, 1885, while visiting London, Charley and Lewis joined the Theosophical Society; Lewis joined the London Lodge while Charley opted for membership-at-large. During this visit the brothers were made aware of the Fifteenth General Meeting of the Society for Psychical Research, which was to be held in the rooms of the Society of British Artists on June 24, 1885. The S.P.R. was critical of Blavatsky, and Charley “made a vigorous protest in [Blavatsky’s] defense.”

Mohini Chatterji.

Sometime during this period, a connection was made with Mohini Chatterji, who would travel to Dublin and help prepare the scaffolding for the future Dublin Lodge of the Theosophical Society.

~

Back in London, W.T. Stead shocked society with his serialized exposé “The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon.” Stead’s undercover investigation revealed a complex British-based international network of prostitution and child sex-trafficking which incriminated some powerful and wealthy elite. The shock for society was not the revelation of deplorable vice, it was that Stead chose to drag it into sunlight. The result of his investigation changed British law, but he himself would serve three months in prison for interacting with prostitutes during his reporting.

~

In the autumn of 1885, Charley was enrolled in Trinity College, and was among top of the Honor List upon entrance. Charley was now “absolutely convinced that Sanskrit,” would be the “culture-language” of the future, “destined to supersede Greek as the instrument of the highest spiritual education, as Greek superseded Latin at the Renaissance.” Though Charley admired Max Müller for bringing to light the thoughts of “vanished races of men, whose name memory has ceased to whisper along the deserted corridors of time,” he differed with regard to style. Charley believed the purpose of translating was “to seize rather the spirit than the mould…to deal with ideas and ideals rather than with systems of words.” He enrolled at Trinity College as a non-degree seeking student, to study Sanskrit under Professor Robert Atkinson, in preparation for the Indian Civil Service.

Atkinson, (the man who delivered the lectures on the Aryan-Celtic origin theory in 1882,) was regarded as a “scientific philologist,” who was interested primarily in the analysis of the structure of language, rather than its literature. His pedagogy impressed upon students like Charley, the principle of law in language, as opposed to theories of “sporadic changes.” Of the South Asian languages, Atkinson confined himself to Sanskrit grammar, the language of the Vedas, learning by heart the intricate grammar of Pāṇini, and partially writing a Vedic dictionary. He was also a pioneer in Gaelic philology, and during the time that Charley and Yeats formed the D.H.S., Atkinson delivered an inaugural lecture on Irish lexicography.

Mir Aulad Ali & William Fletcher Barrett.

Yeats states that “sometimes a professor of Oriental Languages at Trinity College, a Persian, came to our Society and talked of the magicians of the East.” This professor was Mir Aulad Ali, who lived at 129 Leinster Road, the next-door neighbor of Charley, who lived at 131 Leinster Road, in the Rathmines suburb of Dublin. We might assume that Charley had philological conversations with Ali as both a neighbor, and a student at Trinity. The Dublin Hermetic Society held its usual monthly meeting on the first Saturday in November. Professor William Fletcher Barrett in the Chair Proceedings opened with a Paper on the Theosophic Septenary Constitution of Man by a member in which the subject was treated from the point of view of an independent critic. The remainder of the time was taken up by Professor Mir Aulad Ali who in a very interesting speech criticized the Theosophical movement and its leaders.

Mir Ali, poet laureate in the old kingdom Oudh, was professor of Persian, Arabic, and Hindi at Trinity College. He came to England in 1857 as Persian Secretary to the late Queen of Oudh. After a scandal in the Oudh Embassy, Ali “withdrew himself from a service in which he could no longer remain with the approbation of his own conscience.” The University of Dublin learned of his ability, and without any solicitation on his part, offered him the professorship.

~

The boys developed a friendship with Ellen O’Leary and her brother, John O’Leary, who recently returned from years of exile to his native Ireland. Every week the O’Leary siblings held a gathering in Ellen’s home. Charley, Yeats, and other “young people,” such as Katherine Tynan, T.W. Rolleston, and Douglas Hyde attended. The fatherly John O’Leary was a “lover of the Neoplatonists.” Charley, at various times, would borrow rom him the works by Plotinus, Synesius, the novels of Turgenev, and other works that O’Leary recommended.

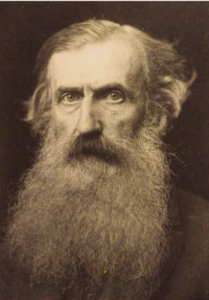

John O’Leary.

By the end of 1885, William Johnston was elected member for South Belfast, with a pledge “to oppose any attempt to establish Home Rule in Ireland, believing the union of this country with England to be the only means of preserving civil and religious liberty to all classes.”

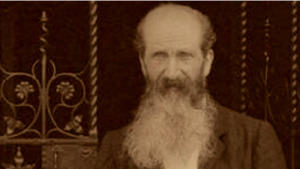

William Johnston.

~

On New Year’s Eve, 1885, Yeats joined the Theosophical Society. Further study of Isis Unveiled, Five Years of Theosophy, and Light on the Path in the months that followed. Charley was particularly fond of the popular Light on the Path, from the pen of Mabel Collins; it was akin to a devotional, and offered something of a Theosophical praxis. Katherine Tynan states: “We heard a great deal of astral bodies, and Mahatmas in those days. [Charley] swept in a number of young people who, having discarded the extreme Low Church in which they were brought up, were ready to turn to something more interesting.”

Trinity College.

That Spring they were paid a visit by Mohini Chatterjee, who inspired Charley and Yeats. In April 1886, Charley applied for, and obtained, the charter for the first Dublin Lodge. Parallel to the establishment of the Dublin Theosophical Society, in April 1886, Charley became the 134th candidate from Trinity to be admitted into the East Indian Civil Service. For the next two tears, Charley would “industriously” study Sanskrit and Bengali and the laws of governance.

~

Eardley Crescent

In May 1887, Yeats and his father moved to Eardley Crescent, South Kensington. It was at this time that he paid his first visit to Blavatsky, who was living “in a little house at Norwood.” Charley met Blavatsky later that summer.

Norwood, London.

Blavatsky expressed her disgust at the British treatment of the Indian people. Charley said that he was under the impression that British “had done a good deal for India in a material way.” The talk then turned to another much-discussed topic of the time, British prejudice of Russians. This antagonism was recently inflamed with fears of Russian advances on the Afghan frontier. “No Englishman ever believes any good of a Russian,” said Blavatsky. “They think we are all liars. You know they shadowed me for months in India, as a Russian spy?”

Vera Petrovna Zhelihovsky.

The effect of Blavatsky’s work was spreading, which brought her great joy, but deep in her heart she felt “cold and lonely.” The accusations of her being a Russian spy was affecting her deeply. Blavatsky’s constant cry was: “Oh for something Russian, something familiar, somebody or something loved from childhood!” She was more than willing, eager even, to spend all her savings to have her sister, Vera Petrovna, and her nieces and nephews with her. It was during this period that she renewed, and deepened, her friendship with Novikova. Vera Petrovna offered to ask Father Evgeny Smirnov, the minister of the London’s Russian Embassy Church on Welbeck Street London, to call on her. Blavatsky was very pleased with the suggestion, but skeptical. Responding to her sister, Blavatsky writes: “Maybe he also takes me for the Antichrist? […] Is it not astonishing that I, a heathen, hating Protestantism and Catholicism alike, should feel all my soul drawn towards the Russian Church.”

This was not a fleeting sentiment. When Yeats paid her another visit, Blavatsky told him: “The [Orthodox] Church, like all true religions, was a triangle, but it spread out and become a bramble bush, and that is the Church of Rome; then they came and lopped off the branches, and turned it into a broomstick, and that is Protestantism.”

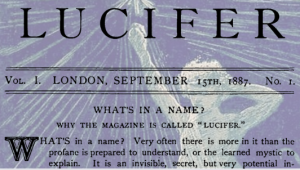

Lucifer (Magazine.)

In September 1887, Blavatsky began publishing Lucifer, her Theosophical journal, which she would later co-edit with Mabel Collins. At this time one of the leading St. Petersburg papers, Novoe Vremya, told the Russian public that Blavatsky had settled in London “with the view of demolishing Christianity and spreading Buddhism,” and that she had “already built a pagoda with Buddha’s idol in it.” [see “Shade of Sattay” (Pt. V.)] Blavatsky, a “holy fool” (yuródivyy,) quickly sent an unpublished letter to the editor of Novoe Vremya which said in part: “In the third [issue of Lucifer] there will be an article of mine (“The Esoteric Character of the Gospels“) in which I stand up for the teachings of Christ, glorifying, as usual, his true doctrine, not disfigured as yet either by Popery or Protestantism.”

~

At the same meeting with Yeats in which Blavatsky discussed the Russian Church, she told him “The power of England would not outlive the century.” It was a low point for Irish and English relations. William O’Brien, a popular Irish Catholic editor, promoted the Plan Of Campaign, and was arrested and imprisoned for “inciting violence” under the British Government’s coercion act. On November 13, 1887, 10,000 demonstrators gathered in Trafalgar Square to protest O’Briens treatment. The police and military escort arrived on horseback, and savagely attacked the protestors. This event was known as “Bloody Sunday.” W.T. Stead, Novikova’s friend and former lover, who witnessed the event, would organize the Law and Liberty League in response. It was comprised of leading activists, including Annie Besant, a popular feminist orator, and editor of the Socialist journals The Link, and Our Corner. Besant was an avowed atheist, and mocked Blavatsky’s magazine, Lucifer, in the November 1, 1887 issue of Our Corner: “It has a very effective cover,” Besant writes, “but the contents are mere ravings.”

W.T. Stead & Annie Besant.

Besant soon developed feelings for Stead, and confessed to him the “very curious influence” he had over her. It was almost spiritual in nature. “Like Diogenes, I have [been] looking for ‘a man’ for some time,” Besant told Stead, “and you seem to me the very one who has head and heart enough for the work.” Regarding her Atheism, Besant explained to Stead: “The horror and the hopelessness of it all nearly drove me mad, and then I won my way into the peace of Atheism which leaves man without an Almighty Torturer while it leaves him also without a Father.” Stead’s idealism offered her new hope, and Besant told him that she longed to work with him to see the realization of a new [Civic] Church. The relationship between Stead and Besant upset Novikova. In late December 1887, Blavatsky sent a consoling message to Novikova: “Your Stead is not an ‘erotic genius,’ see that you don’t ‘fall into the well.’”

~

In 1887, Charley met George Russell, a “somewhat fugitive and retiring personality,” who was waiting for a friend at a lodging house. The boys began to talk about “that literature in which the seers seem to have gone into a divine nature and come back dark and shining and god-intoxicated.” Russell had a mystical experience in his youth when the word Aeon mysteriously entered his mind. When Russell discovered that the Gnostics had applied the word Aeon to the earliest beings in creation, he adopted that as his own name. A confused printer, however, misread Aeon as Æ, an accidental appellation which Russell decided to adopt. Charley introduced Russell to Yeats, who regarded him as “another William Blake.” That December Charley and Yeats co-authored an article for The Theosophist titled “The Speech of the Gods” in which they said: “Of man’s various powers, perceptions and potencies, some belong to the arc ascending from the monera, some to the arc descending from the divine and spiritual ancestors.”

George W. Russell, “A.E.”

All the Johnston siblings by now were experimenting with “all manner of rebelly and Papistical people under their father’s roof,” including hosting séances and adhering to a vegetarian diet. These activities were not unknown to William Johnston, but his work in Parliament kept him engaged in London. During one séance that winter, Yeats became debilitatingly frightened and anxious. He tried to pray, but he could not recall any prayers. He ended up reciting the opening lines of Paradise Lost instead. Perhaps owing to this, Charley prevented the sensitive Russell from attending any séances.

Blavatsky.

When Yeats next saw Blavatsky in the last week of January, 1888, she was living at 17 Lansdowne Road, Holland Park. Yeats writes that the Theosophists who surrounded her all looked to Ireland “to produce some great spiritual teaching.” Yeats, during this period, was dredging the memories of his youth, and began writing John Sherman. He based the titular protagonist on himself; the other characters, such as Reverend William Howard, were an alloy of the personalities of Charley, Dowden, and John Butler Yeats. Readers would find direct inspiration from the excursions Charley and Yeats made to the cromlechs and Ireland’s Eye.

~

On February 24, 1888. Blavatsky wrote a letter to Stead. “I hear from our mutual friend, [Novikova,] that you do not hate me as I thought you did. She goes even so far as to tell me that if I write to you, you will come to see me. I hope it so.” Stead did meet with Blavatsky: “I was delighted with, and at the same time somewhat repelled, by Madame,” he writes, “but we got on very well together […] certifying that I might call myself what I pleased, but that she knew I was a good theosophist.” Throughout the winter, Besant would continue expressing her admiration to Stead. In March she said that he was “in a very real…a messenger of God to me.” In April she would confess her love to him, and state that she hoped he shared her feelings. Despite his marriage, Besant assured him, Stead could tell her that “you ‘loved me best.’” This, however, was not the direction Stead intended for their partnership. He would not give up his wife and children for her. He decided to visit Russia for a prolonged visit, and gather material for a writing project. Novikova wrote a letter to Stead: “I was a little sorry to have heard of your movements first from a stranger.”

Maud Gonne.

While in Russia, Stead met Maud Gonne, an Anglo-Irish nationalist who was staying in St. Petersburg with Princess Catherine Radziwill. Curious to know why Stead was in Russia, Radziwill asked Maud to investigate, which Maud did over a series of lengthy discussions. Stead was a man with “puritanical beliefs,” Maud thought, who was at constant war with the sensual part of his nature. This, according to Maud, “induced in him a sex obsession.” It seemed that he could talk of nothing else, and introduced the topic in nearly every conversation, regardless of the subject. This was “rather repellent to a girl who hated such talk,” and Maud told him so. This compelled Stead to compose “a very foolish, and very amorous letter, endeavoring to explain.” Maud was unsure of the wisdom in responding to the letter, and left it in her writing-case on the table in her room.

Maud returned one day from a drive, and found Princess Radziwill hosting Novikova, whom Maud had only casually met at one of the many parties she attended with her host. Not long after, Maud found Novikova waiting for her in Radziwill’s parlor. After only a few minutes of uninteresting discussion, however, Novikova departed. The following morning Stead called Maud in a state of great agitation, accusing Maud of “a cruel horrible thing.” Novikova evidently told Stead that Maud showed her the contents of Stead’s letter, and laughed at his amorous ambitions. Maud explained that no such event occurred, and that she hardly knew Novikova. She then remembered Novikova’s unexpected visit the day before, and went to her writing-case. The letter was still there. Novikova, Maud reasoned, must have opened the case and read the letter before she returned home.

Maud was angry, but upon seeing Stead so forlorn, she playfully tried to comfort him “to soothe his vanity if not his love.” Stead admitted the possibility of jealousy being the cause of Novikova’s strange behavior and told Maud a story which she found deeply interesting. “[Stead] told me that the scene with [Novikova] the night before had been very painful,” writes Maud, “she felt he had betrayed her by his too evident admiration for me and had tried to turn him against me by saying that I had laughed at him with her, and showed her his letter.” When Maud bid farewell to Stead, he promised to help her if she ever needed him.

~

Elsewhere in the Russian Empire, Vera Petrovna was mourning the death of her son, Valya, a student at the Institute of Railways, and only financial support of the family. He died from tuberculosis on May 20, 1888, at the Londonskaya Hotel in Odessa. He was buried three days later in Odessa’s Old Cemetery. Blavatsky sent money to Russia so that her sister and niece might join her in London.

Londonskaya Hotel, Odessa.

~

In early June 1888, Charley arrived in London with Claude Falls Wright, a neighbor in Dublin who was interested in meeting Blavatsky and joining the Society. (More on Wright here.) The primary reason for Charley’s visit, however, was to take the last of the Examinations, as it was the close of his second year of probation. Upon completion of this notoriously difficult test, it would be decided whether or not he would be qualified for the Civil Service of India. While Charley sat for his Examination, another event was brewing in London’s East End.

THE AGONISED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS:

INTRO: CHARLEY.

I. WITCH TALES.

II. CARELESS WHENCE COMES YOUR GOLD.

III. THE TIMES ARE CHANGED.

IV. DENIZEN OF ETERNITY.

V. DOMOVOY.

VI. WITH LOW AND NEVER LIFTED HEAD.

VII. IMPERIAL GOTHIC.

VIII. THE SERVANT OF THE QUEEN.

IX. THE DWELLER ON THE THRESHOLD.

[APPENDICES]