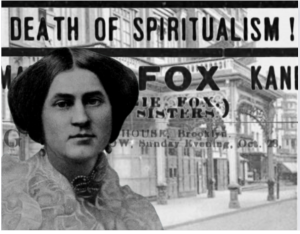

THE SHADE OF SATTAY.

⸻

This is the story of Govindarao Sattay, the first male Brahmin to visit America in 1884. He would experience both generosity and malice in that country, including imprisonment for declaring his beliefs. Sattay would ultimately die in New York, and be the first South Asian of any caste to be cremated in America. Paving the way for the likes of men like Swami Vivekananda, I think his name, and legacy, merits remembrance. I hope this account contributes to that endeavor. This is not a biography of single person, however, rather the biography of an idea. Sattay’s story does not end after his death, as the reader will discover. [A longer serialized version of this story titled “Out-Castes” can be read here.]

⸻

PART I.

~

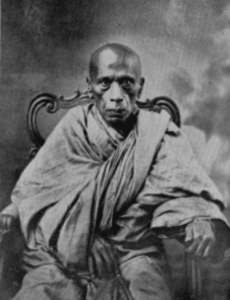

Govindarao Sattay was born in Sholapore, India, around the year 1845. He was a Chitpavan Brahmin, who adhered to a strict vegetarian diet, and wore the sacred threads, the zānave, across both shoulders and chest. His spiritual life played an important role in his life, and he prayed a simple prayer twice a day: “O Thou who givest life to the universe, fill us with thy life. Thou hast created all, to Thee we must return.” Of his early life, little was known, “except that he was married, had one son, and lost his wife while the child was still young.” He was educated at the College of Madras, spoke seven languages, possessed “remarkable conversational powers,” and was familiar “with the best English authors.” He began his career as an accountant in Madras, and by 1883 he was working in the Calcutta Post Office in the employ of the British Civil Service. “The English give no opportunity to the masses of the people’s to learn more than the rudiments of letters,” Sattay would state. “To educated Hindus, only clerical positions were ever assigned in the Civil Service.”

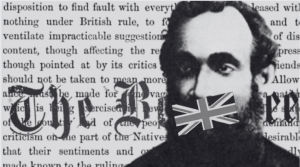

His critique of the British extended to the Christian missionaries in India, where, in Calcutta alone, fifty sermons a month were delivered by Methodist preachers to “heathen” audiences. Sattay’s compatriots initially presented the missionaries “basketsful of all kinds of vegetable dainties,” but when they discovered “bones and feathers of innocent birds and beasts,” on the property around the missionaries’ houses, the gifts ceased. The “religionists from foreign shores found many converts when they first arrived,” Sattay would state, but the Indian people found “that beneath the glitter there [was] much lead.” Though Sattay “accepted the teachings of Jesus as an evolution of the teachings of the Shastas,” he “refused to make a separate profession of truths which he believed to be included in his native faith,” and would debate the missionaries in open-air discussions “largely attended by the natives.” Provocation was not necessarily his goal, but Sattay, like the other natives of India, had few options to ventilate their grievances. “The censorship of the press restricted the freedom of patriotic expression,” Sattay would say, “[the] present hope of the emancipation of the country was nothing.” Surendranath Banerjee, the editor of The Bengalee, for example, was imprisoned in May, 1883, by the British for daring to publish comments in his paper that were critical of the judiciary system of the British Raj.

Surendranath Banerjee.

The social scaffolding of India, which served the people since antiquity was in disrepair according to Sattay. In his estimation, this was due to a failure on the part of the Brahmins who abused their sacerdotal authority for personal gains. “Our warrior classes have been exterminated twenty-one times by the Great Parashurama, and our Bhattacharyas extinguished the warmth of patriotism of the other classes.” For Sattay the best hope for the people of India “was in the education of the Hindus in Western arts.”

Sattay denied that there was increased material prosperity of India under British rule, and believed that “famine in India was unknown before the advent of the English.” British democracy was also a myth “The rule there was of the sword, and by the sword,” but “not an arm, not a knife nor a stick,” was permitted to any Indian unless in the service of the crown. “An Englishman could kill an Indian and exculpate himself by his own statement before the courts,” Sattay said. “The Eurasians […] though numbering only about 40,000 or 50,000 in a population of 250,000.000, are politically more powerful than the natives, as had been proven by the Ilbert Bill controversy.” The Ilbert Bill would prove a catalyst that changed the trajectory of Sattay’s life. Introduced in 1883, the Ilbert Bill proposed an amendment to the code of criminal procedure and allow Indian magistrates jurisdiction over Europeans in India. On August 23, 1883, many Europeans assembled in the Calcutta Town Hall to consider what measures to take to ensure the bill would not be passed. Sattay, who was present at the meeting, described experience in a letter published in the Times of India:

I attended the Great Town Hall Meeting […] I took my seat between two pillars, and I shortly after found that the gentlemen sitting around me could not bear the sight of a native among them. Two of them actually tried their best to induce me to leave the seat I occupied. I boldly bore all the silly remarks they made, and when the speeches commenced, and they found that I did not join the audience in their cheers and applause, and also in their groans and hisses, with all sorts of expressions which resounded through the hall, two of them gentlemen sitting to my right and left kept pricking me with pins to force me to join their demonstrations, and when I could no longer bear the sufferings, I joined them, though much against my will, so that I might no longer be teased by them. Yet they were not satisfied, and one of them, having remarked that my clappings were not loud enough to be heard, snatched my umbrella from my hands, and stamped it forcibly on the floor. At the close of the meeting, I made my way to the platform and tried to speak a few words to the effect that the attitude taken up by them was against the principles of Christianity. But no sooner had I opened my lips than they all rose and resounded the hall with their hootings and hissings. I was immediately surrounded by several of them, and one of them pulled me down the platform. I was almost suffocated and crushed, but I soon made my escape through the crowds. Is this treatment in keeping with the doctrines of Christianity?

Calcutta Town Hall.

~

Two days later, while Sattay was still recovering, an account of the meeting was published in the Friend Of India and Statesman: “Every section of the European community was represented largely, and the speakers were at times unable to control the deafening applause with which any special expression of opinion was greeted.” Just above that column there appeared another article titled, “A Brahmin Lady Medical Student In America.” It was a reprint of a letter from an American missionary friend of the eighteen-year-old Chitpavan Brahmin woman, Anandibai Joshee, who recently left India to study medicine in the United States in April, 1883.

Ocean Grove, New Jersey,

June 19, 1883.

I sit down to tell you of a visit my sister and I made last week to Mrs. Joshee. She has probably written you that her friends met her promptly on the arrival of the steamer, and took her at once to their home in [Roselle.] The lady with whom she is stopping is very agreeable and cultivated. […] They have two very dear little girls, about seven and nine, so Mrs. Joshee’s opportunities for improving in English are very good […] She has learned a good deal since she left the shelter of her own home, and she has conducted herself with great modesty and propriety. She seemed very happy to see me, and took me with great pride to show me her own room, and how neatly her friend had arranged it for her comfort. I smiled when I remembered that she had told me at sea that she hoped she would be allowed to cook for herself in her own room, for she prepared her own Indian food. If she were not well-balanced, her head might be turned with numerous newspaper notices. We are a news-loving people, and the novelty of the arrival of a Brahmin lady to study medicine has attracted a good deal of attention; but she receives it all very quietly.

Sattay was naturally curious about Anandibai, and after his experience at the Town Hall he began to think “very seriously, of organizing a movement for the emigration of his people, that they might ‘escape from British rule.’” He decided he would follow in the footsteps of Anandibai, and “see for himself what [America] offered.” This was a major decision, for as Sattay writes: “A Hindoo can not cross the ocean and go to Europe or America without losing his caste.” Anandibai was the first Brahmin woman to travel to America, and few, if any, Brahmin men had dared make the trip.

~

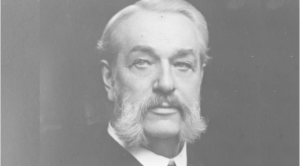

Sattay sought out Anandibai’s husband, Gopalrao Vinayak Joshee, a Brahmin postmaster who lived in the city of Serampore. Gopalrao, a graduate of Wilson College in the Bombay Presidency, held unconventional views, especially with regard to women and education, and at forty-one, was nearly twice the age of his wife. The Joshees tried, unsuccessfully, for several years to find an institution in India where she could study medicine. A letter regarding this pursuit, which was published in The Missionary Review, caught the attention of Theodocia Carpenter of Roselle, New Jersey, who offered to sponsor Anandibai in America. In October, 1883, Anandibai would begin her studies at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. When explaining his motivation for encouraging Anandibai’s education, Gopalrao stated:

I [thought] for a long time that medicine was one of the best studies to be taken up by those who wish to do good. When a boy I read the story of Howard, the philanthropist. I thought I’d like to do as he did: I went to a hospital in Poona to see what I could do for the suffering and wash their wounds, but I found I could not bear the sight. I believed early that woman can elevate man if she be well educated. My first wife was studying when she died. I then tried to get a young girl I could educate. I married my present wife when a mere girl. I sat by her day and night and taught her till she was able to come to America and prosecute her studies.

Gopalrao was as critical of the British as Sattay. “I hate the English from the bottom of my heart for their cruel oppression of my country and my people,” he said. “It does not show itself [among the Indian people,] because it dare not be shown, but it is there, gathering strength and rancor with every new wrong.” His views on English missionaries were likewise unfavorable. “They don’t lean sufficiently on the native element,” said Gopalrao, but added: “The Catholic missionary, on the other hand, stands by his people.” This provisional addendum for Catholic missionaries was likely informed by Pandita Ramabai, a cousin of Anandibai, who converted to Catholicism in England, in September 1883, and was widely discussed at the time.

Gopalrao Vinayak Joshee c. 1894.

~

One of the few people who openly supported Ramabai was Jyotirao Phule, the leader of the campaign against “Brahminocracy,” who re-purposed the Marathi term dalit to describe the “untouchables” born outside of caste. Gopalrao supported Phule’s cause, as evidenced by his friendship with Protap Chunder Mazumdar, a Shudra member of the Brahmo Samaj who was, at the time, in America promoting his book, The Oriental Christ (1883.) Anandibai, writing to Gopalrao at this time, said: “I feel proud to mention that the Bengali gentleman Babu Protap Chunder Mazumdar has received much acclaim here.” Phule and his wife, Savitribai Phule, both pioneers of women’s education in India, likewise supported Anandibai and Gopalrao.

~

The liberality of their thought led both the Joshees and Phule into membership in the Theosophical Society. Gopalrao joined in 1879, while Anandibai joined on March 11, 1883, just weeks before leaving for America. Phule joined the society a year earlier in Poona, in August, 1882. Founded in New York City in 1874 by Col. Henry Steel Olcott, Helen Blavatsky, and William Q. Judge, the Theosophical Society was a transnational spiritual movement that made its headquarters in India in 1879. The society championed religious pluralism, emphasized the importance of Eastern traditions, and freely explored the noetic potentialities in the human experience. With ideas counter to those of normative Christianity, the missionaries in India viewed the organization with suspicion. Of the reason which Gopalrao joined, it was said:

[Gopalrao] saw Madame Blavatsky several times in 1879 in the Bombay Presidency. Of course he “took no stock” in the Theosophist theory about “adepts,” and all the rest of it, but he considered that the effect of discussion by Europeans of Oriental formulas with reverence and respect in the presence of the natives was to give the latter a better opinion of themselves.

Anandibai’s interest in the movement was not passive. Writing to her sister in late 1880, she states:

I think you have heard of Madame Blavatsky and Colonel Olcott. They are making wonders in India. The papers are full [of] the account of the occult phenomena of Blavatsky. She is [a] staunch advocate of Vedic philosophy and asserts that all the new things discovered or invented were formerly in practice in India.

Phule was likely introduced to the Theosophical Society through his friend, Tukaram Tatya, a successful merchant in Bombay of the Bhandari caste. When working for the Walcot Company in his youth, Tukaram met Phule and other lower-caste reformers of Poona, who opened his eyes to the inequality of social division. Tukaram would write Jalibheil Viveksar (1861,) the first book written in Marathi which critiqued Hinduism’s religious hierarchy from the perspective of a lower-caste adherent. Phule, who published Jalibheil Viveksar, praised the work for its critique of the Brahminic monopoly of learning and authority. Tukaram joined the Theosophical Society in 1880, two years before Phule, and would become the de facto leader of the Bombay Branch when the Theosophical Headquarters relocated to Adyar, India. With the desire to elevate native scholarship, Tukaram would establish the Theosophical Publishing Fund in Bombay, and publish works with English translations, and in Indian vernaculars, pertaining to philosophy, metaphysics, the Vedas, and the Upanishads.

(Left) Mahadev Govind Ranade (Center) Tukaram Tatya (Right) Jyotirao Phule.

~

The author Caroline Healey Dall states that Sattay left Calcutta in April, 1884, on a ship named The Valiant, but “the vessel sprang a leak, and the captain put into Mauritius to unload.” Dall states that due to the necessary repairs of the Valiant, Sattay was detained in Mauritius for nearly four months, during which time he worked as an accountant. “It is probable that Anandabai had written to him enthusiastically about her new home,” Dall writes, “for she always said that her first year in America was the happiest year of her life.” Dall was probably mistaken with regards to the name of the ship on which Sattay embarked. H.M.S. Valiant, in the service of the British Navy, was not a mercantile ship, nor was it stationed anywhere near Calcutta at this time. The Valiant would be involved in an accident in Bantry Bay, Ireland, in July, 1884, but the details of that accident do not match the details which Dall provides. The only shipping incident at this time which resembles Dall’s narrative, is one which involves the Norwegian barque, Iphigenia, bound for the Cape from Calcutta in early May, 1884. The Iphigenia was damaged at sea, and began to leak at a rate of two inches per hour. Her crew was forced to jettison five tons of cargo and dock at Diamond Island near Rodrigues, Mauritius. If we accept the key points of Dall’s account to be true, then it is more likely that Sattay left Calcutta on board the Iphigenia. While detained at Mauritius, Sattay investigated the living conditions of the coolie laborers, a topic of which was widely discussed at the time.

~

After discussing the matter with Sattay, Gopalrao decided that he, too, would travel to America. “The English missionaries […] make attacks on my religion and customs,” said Gopalrao, “I want to find out what is fact and what is falsehood.” This decision would have been made soon after meeting Sattay, for Gopalrao states that during a conversation with the President of the Theosophical Society, Col. Olcott, he made his intentions known that he planned on traveling to America “as a mendicant.” This meeting would have occurred before February, 1884, at which time Olcott left India for an extended sojourn in Europe. Gopalrao states that he left India without any plans for food or lodging and only $2.50 in his pocket, just enough to pay for his passage to Rangoon, which he reached on June 22, 1884.

~

Around the time that Sattay and Gopalrao began their trek to America, news of a conspiracy reached Olcott, who was then in Paris with co-founders, Blavatsky and Judge. Emma Coulomb, a disgruntled former member of the society was planning to discredit the Theosophical Society by disseminating insider information to the missionaries of the Free Church of Scotland, and other hostile actors. The Scottish mission, then in the headlines for allegations of sexual impropriety at their school in Calcutta, were only too happy to deflect the vitriol toward an easy target. Judge was dispatched to India to investigate the matter. Judge left England on June 18, 1884, on the S.S. Clan MacGregor, and arrived in Bombay on July 15, 1884, where he was debriefed on the situation by Tukaram. Five days later, en route to Madras, Judge lectured in Poona, where he met the social reformer, Mahadev Govind Ranade, and very likely encountered Phule. “Even the coolies in the street have larger brains than the same kind of man in the West,” said Judge at this time. “It is the duty of the Hindus to furnish to the West, and to the world, the truth in philosophy, the truth in morality, and the truth is science.”

A thirty-two year old lawyer from New York, Judge had little love for the English. Growing up in the “Docklands,” a “very poor locality” on the fringes of Dublin, he knew the hardships endured under British rule. His life changed in 1860 when his mother, Alice, died in childbirth in their family home at 36 Seville Place. “I have seen ghosts ever since I was a boy,” Judge would later say, “my mother, being dead, appeared at my bedside and looked down on me.” At thirteen, Judge and his surviving siblings immigrated to America with their father, Frederick, arriving in New York on July 11, 1864. Taking root in Brooklyn, Frederick raised the children “under the spiked yoke of hard Methodism.” Judge became an active member of the church, and was praised for involvement in the Young Men’s Christian Union at the Fleet Street Methodist Episcopal Church. It was through the church that Judge met Ella Miller Smith, a Brooklyn grammar-school teacher, and graduate of The Packer Collegiate Institute (For The Education Of Females In The City Of Brooklyn,) whom he would marry in September, 1874.

(Left) George Pierce Andrews. (Middle) E. Delafield Smith. (Right.) Henry Steel Olcott.

In the early 1870s, Judge began work as a clerk near City Hall in Manhattan, where he studied law under Assistant Attorney George Pierce Andrews, and District Attorney, Edward Delafield Smith. It was through this connection that Judge first met Olcott, as both Andrews and Smith worked with Olcott during the trial of Soloman Kohnstamm.

Outside of his network in the church, Judge ran with a circle of friends that included colleagues from City Hall, and reporters from nearby “Printing House Square,” such as David A. Curtis, Edward Page Mitchell, and Frank Church. Judge would attend poker nights with the journalists, where he earned the nickname “The Adept,” because of his “undoubted skill at the game.” Mitchell, editor and correspondent for The Sun (New York,) described Judge as being “a smooth spoken-person with contemplative eyes in which lurked both professional sagacity and somewhat of Oriental craftiness.”

In the summer of 1875, Judge and Ella became the parents of a baby girl, whom they named Alice, presumably after Judge’s late mother. The young family lived with Ella’s widowed father, a shoe-dealer named Joseph Smith, at 160 Gold Street in the Vinegar Hill neighborhood of Brooklyn, known colloquially as “Irish Town.” At this time, Olcott was writing extensively about his investigations of occult phenomena with Helena Blavatsky, whom he met a year earlier at a séance conducted by the brothers, Horatio and William Eddy, at their homestead in Vermont. Upon their meeting, Blavatsky allegedly summoned the spirit of Bessie, Olcott’s daughter, who died just before her second birthday. Bessie, Olcott states, reached out her hand to caress his face, and one would imagine, provide closure to her father. “At my request,” Olcott states, “[her hand] came back for me to kiss it.” On August 30, 1875, Olcott wrote a letter to the editor of The New York Tribune in defense of his investigations, stating:

If the priceless treasures of the Alexandrian Library had not been used to heat the public baths, the “Lost Arts” of the the ancients, including the art of communing with the dead and the power to look beyond the veil to our future home, might not be now “lost” to all but a select few in the Oriental fraternities.

Judge contacted Olcott requesting an introduction to Blavatsky, who was then living at Irving Place in Manhattan. Having received an invitation from Blavatsky, Judge called upon Blavatsky with a young colleague, and future Attorney General for the Kingdom of Hawaii, William Richards Castle. Impressed with her powers, Judge and Castle returned a week later, marking the beginning of what would be The Theosophical Society. “Why need we only meet and talk,” asked Blavatsky, “why not materialize; why not, at the present moment, form a society and undertake the study of truth in connection with this great and absorbing subject?”

(Left.) William R. Castle. (Right) David A. Curtis.

Three years later, the summer before Olcott and Blavatsky would move the headquarters of the Theosophical Society to India, Judge and his family were staying in Asbury Park, New Jersey. It was a community in sympathy with, and adjacent to, the Methodist camp-meeting resort of Ocean Grove, led by Rev. Ellwood H. Stokes. Despite their claims to health and rejuvenation, Ocean Grove and Asbury Park operated under notoriously unsanitary conditions, of which the health officials of the communities were well aware. Rev. Stokes admitted in 1878 that “vast numbers” of people abandoned “every sanitary rule and regulation observed at home,” when attending the meetings. Even with this knowledge, on August 29th, 1878, during a service attended by six thousand people, Rev. Stokes personally baptized a number of children. Two days later Judge noticed that Alice was running a high fever. Four days later, on September 2, 1878, Alice died from diphtheria. Her death had a profound, and life-long, effect on Judge.

(Left) William Q. Judge (Center) Alice Judge. (Right) Ella Judge.

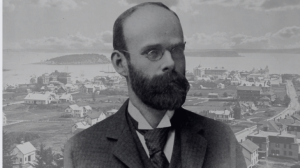

When Olcott and Blavatsky departed America in December, 1878, Judge was left directionless and alone in New York. Writing to Olcott in April, 1879, Judge confessed: “Often there is much sorrow and longing in my heart after the little one [has] gone away.” With Alice gone, Judge’s purpose in life was channeled into cultivating the remnants of the Theosophical Society in America until such a time when it would produce a sustainable spiritual harvest, even turning down a promising job offer from Castle, who returned to Hawaii shortly after meeting Blavatsky. “In [Judge’s] letters to me,” Castle writes, “he expressed his contempt for the trammels of Christianity and hoped I had become freed of its servile bondage.” Judge’s disappointment with “Churchianity,” which he differentiated from Christianity, the true teachings of Christ, are found in his many letters to Olcott at this time. Judge writes: “The very first step necessary [in America] is to show the people how wrong is their estimate of the East, and what lies they have been told by the missionaries.” The “damn preachers make me furious,” he added.

~

Judge moved to 116 Willoughby Street in 1881. After the departure of Blavatsky and Olcott for India, Judge, for many years, “was the only Theosophist in New York [and] about the only man in the metropolis who knew a philosophy of that name existed.” Judge was determined to hold meetings, even if he was the only one present. By January 1883, Judge befriended his neighbor; a journalist and fellow named Laura C. Holloway. She hosted Sunday evening discussions in her home at 181 Schermerhorn Street, Brooklyn, with like-minded students of mysticism. “The visitor would almost surely be met by people of distinction in literary or social circles; prominent among them was Edward Dwight Walker, writer and editor for Harper’s Magazine.” Holloway reflects of this time:

In speaking of his personal life to his friends, [Judge] had several times told them incidents connected with his little daughter, an only child, whose sudden and unanticipated death had, as he expressed it, “about broken his heart.” And, later, when writing about the grief it was costing him to cast anchor and set sail for India, he referred again to the loss of his child, and mentioned this sorrow as one of the sources of his present strength.

Edward Dwight Walker. Laura C. Holloway.

~

Judge focused his energy into revitalizing the malnourished Theosophical Society in America, and by the close of 1883 his work was beginning to yield results. At the time the new word “Aryan,” and the concept of “Aryan Christianity,” was filling the columns of the New York papers. On October 28, 1883, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle printed a lengthy excerpt of Mazumdar’s Eastern Christological conception:

Keshub [Chunder Sen] (the Brahmo leader) speaks of Christ as the prince of idealists. And his religion is spoken of as supreme idealism. And it is in this idealism that India has a hold on the real nature of Christ and Christianity. The East has always been the home of idealism. The prophets and seers of Asia penetrated the veil of phenomena, and saw behind it the life and meaning of all things. Exuberant nature, making slender calls upon physical energy, invited the mind to communion and contemplation. Zoroaster on the mountain tops, the old Aryan sages of India in the deep wood or romantic river banks, found the whole world idealized before them into the purposes and perfections of the Great Spirit.

Protap Chunder Mazumdar.

This was printed concurrently with the serialized translation of Marc-Aurèle et la Fin du Monde Antique, the latest work of the French philologist and historian of religion, Ernest Renan, which appeared in The Sun. One chapter stated:

Among the debased nations of the East, Christianity is a religion of very moderate merit, inspiring very little virtue […] Christianity has been truly fecund…In the beginning a wholly Jewish product, Christianity has come in this way, in the process of time, to shed almost every trace of its ethnic origin, so that the contention of those who proclaim it the Aryan religion par excellence is, from many points of view, well-founded […] The Bible has in this way borne fruits not its own; Judaism was only the wild slip on which the Aryan race has grafted its flower.

Ernest Renan.

Inspired by this new vision of a mystical restorationist Christianity, Judge decided that his new Branch would be called “The Aryan Theosophical Society of New York.” The epithet Aryan indicating that the Society was separated from the mainline Christian world.

~

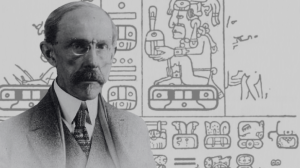

On October 6, 1884, after conducting his investigation in Adyar, and before returning to New York, Judge attended the inaugural meeting of the Samuskrita Basha Abhi Virtini, the new Sanskrit school at Madras Christian College. Ragunath Row, a fellow Theosophist and former Deputy Collector of Madras, occupied the chair. He was a “man of power,” who possessed a warm and cordial sense of humor, and whose bright blue eyes were something of a rarity among his people. In 1885, Ragunath Row would be among the founding members of the Indian National Congress, as well as its sister movement, the Indian National Social Conference, whose goal it was to persuade Indians to adopt a modern, progressive stance in their moral behavior. The paper read that evening, “The importance of Sanskrit literature,” expressed the sentiment of Phule’s anti-Brahminocracy by declaring that “the Brahmin priesthood brought India down to its present low level,” and that, “a study of Sanskrit would raise India among the civilized nations of the world.”

~

On November 15, Judge returned home to New York on the S.S. Wisconsin, by way of London, and arrived on November 26, 1884. The Theosophist A.E. Smythe, who first met Judge on the Wisconsin during this trip recalls:

There were eleven of us on the Guion liner Wisconsin in 1884, when I first met him on his way back from India. He was reticent about India and his business there and no one on the boat knew him as a Theosophist, but he talked mysticism and mystical subjects with me, and I presume with others. A daughter of the theologian, Dr. Geikie, with her husband, a rich New Yorker, an American dentist who had been practicing in Paris, two Pennsylvania Dutch girls who had been touring Europe, and a few other etceteras, and Judge formed the cabin group. He walked the decks with those who needed a companion, he played cards, except on Sunday when he drew the line, he played deck quoits, and he chatted, but always with a certain aloofness, and he retired for long periods to his cabin. It was November and cold and he wore a Tam O’Shanter as several others did and an overcoat and muffler. He looked old and pallid and had I been told his age was 33 I would have said it was 20 years out. We knew nothing of āveśa in those days, and still less of the battle that had gone on at Adyar for the reputation of H.P.B. These things must have weighed heavily on the mind of Judge. Yet he was cheerful and thoughtful of others, and as we neared the end of our ten-day voyage he drew up a memorial, decorated with his attractive penmanship and we all signed it as a tribute to the Captain for his courtesy, kindness and care.

PART II.

~

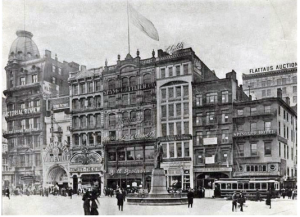

Judge arrived in New York on November 26, 1884, and “quietly took up his duties, and as patiently performed them as though he had never been away from them.” The Aryan Theosophical Society held its fortnightly meeting above a beer saloon at 35 Union Square, in a hall which they rented from a fraternity of Odd Fellows. General Abner Doubleday, an early member of the original New York Branch, was respectfully elected President, while Judge was named the Secretary of the Branch.

Union Square South c. 1880.

~

Curiously, Sattay, too, arrived in New York in November, 1884, about the same time as Judge. He soon made his way to Roselle, New Jersey, to visit Anandibai and Theodocia Carpenter, bearing gifts of saris and keepsakes from home. The occasion marked the first opportunity in a year for Anandibai to speak Marathi. Having devoted much of her time to her studies of medicine and English, she had lost command of her native tongue, which troubled Sattay. Anandabai states:

He thought I had lost all my nationalism and become useless, and so he gave up all hope for me! He declared me totally unfit to return to my country or even show my face there.

The unpleasantries of Sattay’s rebuke must have been resolved, for Sattay’s estimation of Anandibai is overwhelmingly positive in subsequent transactions, and he appears to have endeared himself to Theodicia Carpenter, with whom he retained correspondence.

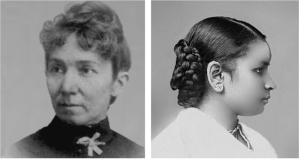

(Left.) Theodicia Carpenter. (Right) Anandibai Joshee.

Sattay then took some time to consider his next moves. His initial idea was to pass the winter with the coolies of British Guiana, who lived in daub cottages on the periphery of their master’s plantation. This idea was abandoned when Sattay learned of the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition, which was to be held in New Orleans, Louisiana from December 16, 1884 until June 2, 1885. Believing that there “would be so much to learn there that [would] be useful to his people,” Sattay postponed his visit to British Guiana, left a sum of money with the Carpenters, and left for New Orleans.

~

While Sattay was visiting Anandibai, Gopalrao was having an unpleasant experience in Siam. “I have not met a human being worse than the Siamese,” Gopalrao states. He soon made his way to Hong Kong, and during an address titled, “India Past, Present, Future,” delivered on November 24, 1884, at Temperance Hall, Gopalrao said of British India:

Where there was unity, there is now disunion; where there was harmony, there is now discord, where there was sobriety and temperance, there is now drunkenness, whose votaries can be counted by millions. We were very honest and faithful in our dealings, and kind and loving, as brothers ought to be. We are now quite the reversal: we are now the greatest liars, deceitful fornicators, and forgers.

In early January, Gopalrao left Hong Kong for Yokohama, Japan, on the steamer S.S. City of Rio de Janeiro. On board the ship, he befriended William Willes, a Mormon missionary to India. Through Willes, Gopalrao learned of the hardships which the Mormons were then facing. In 1882 the U.S. Federal Government passed the Edmunds Act, which outlawed polygamy. The pressure was so great, that by 1885, John Taylor, President of the LDS Church, was forced into hiding. Willes and Gopalrao parted ways in Japan, but they agreed to correspond when Gopalrao arrived in America.

Hong Kong c. 1880.

~

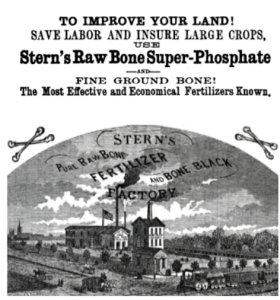

With only $10 in his pocket, Sattay arrived in New Orleans in January 1885. He soon found employment at Stern’s Fertilizer and Chemical Manufacturing Company in the Third District of the city.

Stern’s Factory.

The setting was less than picturesque, but Sattay quickly acquired a knowledge of Western industrial art. Acclimating to the quotidien life in America took longer. “He ate rice, potatoes, oatmeal, corn and sometimes eggs. Frequent were his conflicts with restaurant keepers who sought to insist on his feeding on abhorrent meat.” This discomfort was not a deterrent, as Sattay was willing to advocate anything for his compatriots, “even a meat diet,” if it meant their ultimate “political and religious emancipation.”

New Orleans Docks, 1880s.

~

After lecturing in Japan for a few weeks, Gopalrao arrived in San Francisco, California, possibly on board the City of New York which arrived on March 8, 1885. Anandibai sent word to Gopalrao that Dr. Rachel Bodley, the Dean of the Woman’s Medical College, whom she boarded with, found a job for him teaching Sanskrit. Anandibai did not approve of this, however, suggesting, instead, an alternative:

All colleges already have their own teachers and do not seem to need more. In this situation we must find an alternative ourselves. The one which has occurred to me is to earn money by giving lectures. I can see that this sounds like a clumsy suggestion, but it is the best by far. I am not too proud or greedy, but I too have ambition.

He was soon giving lectures, and attending séances, which fascinated him. Through his connection with Willes, Gopalrao met the Mormons of San Francisco, including Anna Kimball, a daughter of Heber Kimball, one of the original twelve apostles in the early LDS Church.

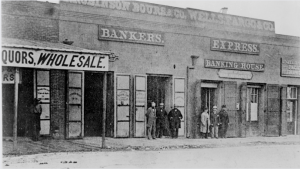

Wells Fargo & Co. Express building, Stockton, California

While in San Francisco, Gopalrao would visit T.Y. Read, “one of the most scholarly and best read men in the town,” and the Wells Fargo’s agent in Stockton. Here Gopalrao would retrieve his regular letters from Anandibai. One letter from Anandibai was in response to an inquiry as to the whereabouts of Sattay. Anandibai writes:

I think I have written to you whatever I know about Govindrao. There is no letter from him since he left Roselle, and that is not my fault.

In a follow up letter on March 30, Anandibai writes:

I need not beg your pardon for the flutter I was in, and I have not uttered a word anywhere about Govindrao, but I cannot help saying that I am severely disappointed at his indecision and lack of purpose. His own words reveal his fickleness. Perhaps I am unduly inquisitive, or have misunderstood matters, but even so, I do not think that I am distorting the truth. He himself has never divulged his plans to me.

~

Sometime in April, 1885, Sattay wrote his own letter to Gopalrao, in which he states that he found much inspiration from Patrick Ford’s newspaper, The Irish World. “Despite the difference in the people, the conditions of Ireland and of India are much the same,” Sattay would say. He proposed to Gopalrao that they publish their own newspaper in America, The Indian World, so they might “expose the frauds of the British rule in India,” and “inculcate patriotism in the hearts of the home patriots.” In the remainder of the letter, Sattay writes:

Sometimes I repent that I was too hasty in leaving our dear land; at another time I feel satisfied that we will be able to secure at least the honor of becoming the first Hindoo-American settlers, paving the way for future crowds of immigrants from British India seeking shelter in this land of freedom.

New Orleans, I find, is the fittest place for our people to begin with. Here our complexion passes for some Southern European nation. In India we are called and’ looked upon as “n—” by the white men, while here the emancipated negroes, as well as the white men, both look upon us as either Spaniards or Mexicans. My friend, had I learned the art of folding our turban I would never have taken the cap in Bengal, and if I should put on a hat here in summer it would be simply to “keep up to the time, place and people,” which, you know, is my motto. My dear friend, strange dress is no doubt an attraction; but change of dress, or even the change of food, does not change our convictions.

Since I left India my faith in the primitive Hindu religion of the Vedic times has become stronger. I have been able to see the mischief done by the subsequent rules and regulations of the Bhāṣyakāra. Had it not been for these religionists, our country would not have come to her present degraded condition. She has been so much split that there is no uniting possible. It is useless to say that 250,000,000 souls form one nation. The Malayalees of Calicut, and the Oorians of Jaganauth are quite different types of people. A combination of fifty-six such sections is almost an impossibility. If there be any bright future for our country, it is at a very great distance.

We want a large number of workingmen to come down and earn their bread at different factories and thus learn the different arts in this country. We want graduates to emigrate. Can this be possible? I wish to see 300 patriot Indians leaving their country, sworn, like the followers of Leonidas, to accomplish their aim.

After this letter was sent, both Sattay and Gopalrao increased their lecturing, granted interviews, and contributed articles to local papers, all for the purpose of providing Americans with Indian perspectives of India. On March 30, hostilities between the Russians and British escalated in Afghanistan, and their opinions on the matter were of great interest to readers. “If the Russians should gain a decisive victory early in the trouble,” said Gopalrao, “there is no doubt in my mind that the Indian regiments would at once join them.” On May 17, Sattay visited the offices of The Times-Democrat (New Orleans,) where he offered his perspective. When asked if Indians preferred British or Russian rule, Sattay replied: “England, without a doubt. It we have, and find its rule tolerable, though offensive. Of Russian rule we know nothing, and naturally bear the ills we have rather than fly into those we know not of. But we should, of course, much prefer to govern ourselves.” He then elaborated on the injustices of British rule:

Mr. Sattay emphatically denies the increased material prosperity of India under British rule, and urged that famine in India was unknown before the advent of the English. Of the democratic character of English institutions, he said nothing was seen in India. The rule there was of the sword, and by the sword. Not an arm, not a knife or a stick, is allowed to any Indian unless in the service of England. The censorship of the press restricted the freedom of patriotic expression and present hope of the emancipation of the country was nothing.

Sattay would soon become the “Bengal Correspondent,” for The Times-Democrat, where his occasional columns offered an Indian’s insight into matters of politics and religion. His critique of British rule continued in his article, “From A Hindoo,” in which he states:

Readers, you can form no idea how the British Government has been working the ruin of the land internally as well as externally. English politicians and Christian missionaries give you bright stories of the brightest possession of England, but to India and her people the English are the darkest rulers she has ever had. Since the advent of those all-absorbing grocers, the great organization of our nationality has been so much disturbed that the caste system, which was the very strength of the Hindus before, has now become the weak side, under present chaos brought on by British rule. […] Now that the world has advanced in the means of rapid communication of the news of one country to the other, it is very necessary that the great nation of nations should be in communication with the several oppressed and struggling nations of the globe. The great aim of the Almighty in creating this ever increasing republic is to elevate and liberate the subject nations of the European monarchs. I therefore wish that the daily movements of the struggling natives of India should be laid before the citizens of the United States, and that the active and noble example of this nation should serve as a lesson to them for their guidance. With such a view, I propose that there should be an exchange of the leading native journals of India conducted in the English language with the leading journals of this country. The Hindoo, of Madras, The Bengalee, and The Indian Mirror, of Calcutta, and The Maratha, of Poona, would be very much obliged to you for your kind acceptance, and at no distant future you will have the credit of sowing the seeds of the emancipation of 250,000,000 of souls, of that almost scourged and devastated country. The whole country, from the East Pacific to the West Atlantic coast know the grievances of the Hindoos, and thus give them a chance of studying the proper way and means of regaining their independence.

New Orleans.

~

Gopalrao arrived in Salt Lake City, Utah, in the middle of June, where he stayed as the guest of William Willes, the Mormon missionary whom he met en route to Japan, and with whom he maintained a steady correspondence since his arrival. He probably made his intention known to Anandibai, who wrote to him at this time: “Be very careful about giving your opinion on any subject, because those who are not Christian or Mormon are likely to cause trouble. Salt Lake City is on your way, so do visit it.” On June 19, 1885, Willes accompanied Gopalrao to the home of Helen Kimball (one of the widows of Mormon prophet, Joseph Smith,) bearing a letter of introduction from her cousin, Anna Kimball. The following day Helen gave Gopalrao a book on plural marriage, in which she wrote an inscription: “That you may be guided by the Candle of God, while journeying ‘over the hills of time.’”

The Salt Lake Temple under construction, 1885.

On the evening of June 23, Gopalrao asked Willes to baptize him in the Mormon church. After consulting Bishop John Sharp, Willes agreed. The Mormon Mission in India closed on June 10, 1885, to baptize a Brahmin would have been a morale boost for the beleaguered Mormons. Gopalrao, however, was a far from ideal convert. On the day selected for his baptism, Gopalrao attended a spiritualist séance. Willes lectured Gopalrao on some of the “peculiarities of ‘spiritualism,’” after which the two men had a falling out. On June 30, 1885, after facing criticism from Willes in the press, Gopalrao delivered a speech at the Josephite Church, with the support of Joseph Smith III. The eldest son of the Mormon prophet, Joseph Smith, Joseph Smith III was the leader of the “Josephites,” a branch of Mormonism which did not accept the practice of polygamy. Taking advantage of the absence of John Taylor (the LDS President,) Joseph Smith III ventured into Salt Lake City to pitch his brand of the faith around the time that Gopalrao arrived. Against the advice of Anandibai, Gopalrao opined freely about the Mormons from the pulpit of Josephite Church, and it was not favorable.

~

By November Gopalrao had joined Anandibai in Philadelphia, where he made the acquaintance of the poet Walt Whitman, and continued to explore the many avenues of American spiritual expression. At a service he attended by the Hicksite Quakers on Race Street, it was said that Gopalrao “made some remarks in approval of Friends principles, which he seemed to think were in harmony with those of his own faith.”

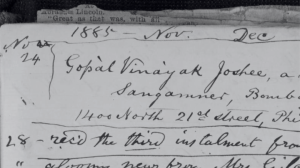

Gopalrao’s name in Walt Whitman’s address book, November 24, 1885 entry.

Days after the Quaker service, Gopalrao stayed as a guest of the Dr. Elliott Coues, in Washington, D.C. Coues was a professor of anatomy at George Washington University, who joined the Theosophical Society on June 7, 1884. A few months before Gopalrao was his guest, he was made President of the Board of Control for the American Section of the Theosophical Society. He also established the Gnostic Branch of the society in his home city, Washington, D.C., which was something of a rival to Judge’s New York Branch. During this visit, Coues and Gopalrao were interviewed by a local paper, in which Coues made some provocative claims:

If everybody knew what Mr. Joshee and I do, the social organism of the world would be thrown into chaos. The knowledge could be used for harm as well for good, and in the hands of bad men, it would be a terrible weapon.

This claim attracted the attention of the zoologist Robert Wilson Shufeldt, honorary curator at the Smithsonian Institution, who questioned the veracity of Coues’ statement. This dispute prompted Judge to issue a public reply: “Bro. Joshee I know very well. All ridiculous impressions should at once cease about him. He is a Brahman and a patriotic Hindu.”

(Left.) Dr. Robert Wilson Shufeldt. (Right) Dr. Elliott Coues.

~

In New Orleans, Sattay continued writing for the local papers, where articles such as “Hindoo Kindness To Animals,” described the dietary practices of his faith. He left his job at Stern’s to begin work at Purves’ Sash Factory, a three-story frame building on Clio and Saint Charles Streets.

View of the Cathedral of St. Louis, New Orleans.

Writing to the Carpenters at this time, Sattay states: “I am in good health. When working in the moss factory, my lungs were affected, but since I went into the sash factory all is well.” On January 12, 1886, not long after Sattay sent this letter, a devastating series of fires broke out in New Orleans, resulting in a tremendous loss of property, especially in the Third Ward. Sattay writes to the Carpenters:

God’s arrangements are always perfect and man has only to move on till he comes to his portion. I had never dreamed that my bread and water were ready in New Orleans. If my means are small, my wants are few, also, and I am quite comfortable here. Although I met a misfortune by fire, and lost all my books, and clothing, it did not, materially, affect me. On the contrary, I am better situated, and prepared for future misfortune. Before the fire my lodgings were in an insignificant quarter and surroundings not at all to my taste. The fire misfortune has brought me closer to better society. In regard to money I have never been ambitious. I came to this place with only $10 in my pocket, and by the simplest mechanical labor, I have been able to send $40 to my country’s national fund. I have at present $60 more in the Germania Savings Bank. I do not require any money from you. If you, or your friend Mr. Joshee should need it, you are free to make use of it. My object in leaving it was not to enable you to help me, but to enable my friends and brothers to help themselves in time of need. Of course the amount is too little for much purpose, but I trust you have deposited it where it will bear fruit. Mr. Joshee writes that he intends to make some provision in America for India and her people, and if he should ask for help, I will remit my present savings from this place.

New Orleans.

~

Jirah Dewey Buick.

While Sattay was settling into his new job, Judge was spending Christmas week in Walnut Hills, Cincinnati, Ohio, at the home of the Theosophist, and homeopathic doctor, Jirah Dewey Buck.

In 1885 [Buck’s] wife joined the society, and the following year, William Q. Judge, during a visit to Cincinnati, called on the doctor, and in his house Mrs. Buck’s two eldest sisters, Delia and Eloise Clough: her two daughters, Alice and Cora, and her son, Edgar, were initiated as members of the society. This made seven Theosophists in one family, and Mr. Judge dubbed them “the Theosophical family of America.” Later several other persons joined, and a branch was formed.

In recalling this time, Buck writes:

I first met William Q. Judge in the winter of 1885. He spent Christmas week at my home in company with Arthur Gebhard, who at that time was greatly interested in the T.S. work in America. Mr. Judge was at that time a devoted student of the Bhagavad Gita. It was his constant companion, and his favorite book ever after. His life and work were shaped by its precepts. That “equal-mindedness” and “skill in the performance of actions” inculcated in this “Book of Devotion,” and declared to constitute “Yoga,” or union with the Supreme Spirit, Mr. Judge possessed in greater measure than anyone I have ever known.

Arthur Gebhard, a fellow Theosophist who accompanied Judge, was involved with establishing a Theosophical magazine with Judge called The Path, which was set to debut in April, 1886.

~

Early in February, Sattay arranged for the Carpenters to send $50 from his funds to Bombay in exchange for a shipment of Sanskrit books. Sattay asked that these works to be distributed to the public libraries of New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C., in honor of Anandibai, and her accomplishment. It is probable that the works were purchased through Tukaram’s theosophical press, which recently published Tukaram’s own popular translation of The Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali (1885.)

~

On February 4, 1886, Gopalrao and Judge lectured before the Aryan Branch in New York; Gopalrao spoke on “Theosophy in India and America,” while Judge discussed Jacob Bohme. It is likely that Edward Dwight Walker was in attendance, as he would join the Aryan Branch on February 21, 1886. Walker, at this time, had left his position at Harper’s Magazine to work on a new magazine called Cosmopolitan. We might assume that he lent his expertise as an editor to Judge with The Path, which was two months away from publishing the inaugural issue. The atmosphere of the New York Branch was one of promise. For Judge, who financed the project, it was a labor of love, for neither he, nor the society, had much money at the time.

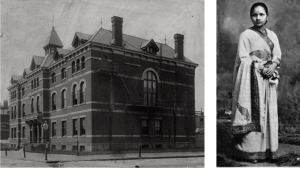

(Left.) Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. (Right) Anandibai Joshee.

~

The writer, Celia Thaxter, developed an interest in Theosophy, and began a communication on the subject with Gebhard, and it is likely that her interest generated significant interest among the New England literati. It was said of Boston at the time:

Buddhism is rapidly becoming a prominent Boston “fad,” and following closely on the heels of Browningism, with a possible case of pushing it to the wall and keeping it there. The new “ism” has not taken any very firm hold, as yet, upon the masculinity of the Hub, but the gentler sex has become largely infected by it, and there is every prospect that it will soon be an all-pervading epidemic with them.

In March Gebhard went to Boston and delivered a small talk on “The Ideals of Richard Wagner, as they bear on Theosophy.” Several Bostonians were in attendance, and a “general discussion on ancient myths in the light of Theosophical ideas was held.”

The first officially recognized T.S. branch in the Boston area was chartered on December 27, 1885 in Malden, Massachusetts, a small town five miles from Boston. Its president was George Ayers, an “exceedingly nervous gentleman with bushy, red whiskers,” who joined the same month the charter was issued. Ayers was most well-known for being the first President of the Nationalist Club, an organization which was formed to “revolutionize the social fabric” after the publication of Edward Bellamy’s novel Looking Backward. A Harvard alumnus, and prominent Boston lawyer, it was said that Ayers would charge someone “for every five minutes you talk with him on legal subjects,” but on the subject of Theosophy, he would talk “by the hour and charge you nothing.”

George Ayers.

~

On March 11, 1886, Anandibai graduated from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, becoming “the first Hindu woman to receive the degree of medicine in any country.” Joining her for the event was her cousin, Pandita Ramabai. The Joshees remained in Philadelphia throughout April, where Anandibai enjoyed the well-earned celebrity which came with her accomplishments. Among the society events they attended, was Walt Whitman’s Lincoln Lecture at the Chestnut Street Opera House, where, after the address, they attended an informal reception with Whitman. Based on an account by author Ella Wheeler Wilcox, the Joshees appear to have attended a meeting of the New York Branch with Coues in Judge’s home:

The other evening I was invited to attend a meeting of members of the Theosophical Society here in New York. It took place in the parlors of a well-known New York lawyer […] a woman physician who is soon going abroad to practice in the European hospitals and several other people well known in the social or intellectual circles of New York. Dr. Coues […] addressed the assemblage with a few interesting explanations of the theosophical idea of the seven layers which compose a human being.

~

After months of planning, The Path finally debuted in April, 1886. In one of the first articles published, “A Prophecy About Theosophy,” Judge explains the prophecy of the Nadigrandhams:

The society is now, April 3, 1885, passing through a dark cycle, which began August 24, 1884; it will last nine months and sixteen days more, making seventeen months for the whole period. By the end of fourteen months next following the seventeen dark months, the society will have increased threefold in power and strength, and some who have joined it and worked for its advancement shall attain gnyanam. The society will live and survive its founders for many years, becoming a lasting power for good; it will survive the fall of governments.

The reviews of The Path were mixed. J.H. Connelly states: “When The Path first appeared, it was a mild joy to the newspapermen who knew Judge. Their occupation seems to cultivate in them a cynical materialism, not readily impressed by metaphysical abstractions…” The review of The Path in The Sun was particularly scathing.

The “intellectual circles” of Boston, we are told, find much food for thought and discussion in the literature produced by wholesale under the direction of Blavatsky and Olcott, and “the current of truth flowing through the society’s channels makes itself felt” in the inquisitive Puritan capital. […] We have received the first number of The Path, a monthly magazine “devoted to the brotherhood of humanity, theosophy in America, and the study of occult science, philosophy, and Aryan literature.” In plainer and simpler words, it is a now exponent of the clap-trap religion concocted by Mme. Blavatsky […] The Nadigrandhams, The Path tells us, are certain books which exist in India, and “resemble the Sibylline books of Rome, which prophesied, it is said, for over 200 years all the important events in the affairs of the Eternal City.”

~

Gebhard returned to Boston, and spoke on Theosophy in the parlors of Sara Bull in Cambridge, Massachusetts, with an audience comprised of Anna Lynch Botta, Celia Thaxter, Julia Campbell, and others.

Home of Sara Bull, Brattle Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Of these women, Julia Cambell, who joined in May, 1886, would become a close friend of Judge. A contributor to Harper’s Magazine, and playwright of some renown, Julia won praise in 1884 for her dramatic retelling of the Salem witch trials in The Puritan Maid. This was followed by a drama called Sealed Instructions which had a very successful run at Madison Square Theatre in the spring of 1885. Her father, James Hepburn Campbell, was the former American Minister to Sweden, and her mother, Juliet Hamersley Lewis was a poet of repute. Despite her successful career, Julia’s life was marked with tragedy. A decade earlier her entire family died; first her two boys, James and Gordon in 1875, and then her husband, Phillip, in 1876. Her boys were still infants when they passed away, and Judge understood well the sadness which lingered from such a loss. In a letter dated April 29, 1886, to an unknown recipient, possibly Julia, Judge writes:

No excuse will, I am sure, be needed from me in addressing a few lines to you in your present sad bereavement, not only because you feel that I write out of sympathy, but also because we both saw the light under the same skies in the same country […] I do not deem it possible for me to enter into a mother’s feelings, but I have been a father from whom a daughter was snatched away in two days while she was in the flower of health.

~

In the second issue of The Path, issued in May, 1886, Judge responded to the criticisms of The Sun, with an article titled “Another Theosophical Prophecy.” In the article Judge “double-downed” on his position, and offered two new prophecies:

The first will seem rather bold, but is placed far enough in the future to give it some value as a test. It is this:—The Sanskrit language will one day be again the language used by man upon this earth, first in science and in metaphysics, and later on in common life. Even in the lifetime of the Sun’s witty writer, he will see the terms now preserved in that noblest of languages creeping into the literature and the press of the day, cropping up in reviews, appearing in various books and treatises, until even such men as he will begin perhaps to feel that they all along had been ignorantly talking of “thought” when they meant “cerebration,” and of “philosophy” when they meant “philology,” and that they had been airing a superficial knowledge gained from cyclopædias of the mere lower powers of intellect, when in fact they were totally ignorant of what is really elementary knowledge. So this new language cannot be English, not even the English acquired by the reporter of daily papers who ascends fortuitously to the editorial rooms—but will be one which is scientific in all that makes a language, and has been enriched by ages of study of metaphysics and the true science.

The secondary prophecy is nearer our day, and may be interesting—it is based upon cyclic changes. This is a period of such a change, and we refer to the columns of the N. Y. Sun of the time when the famous brilliant sunsets were chronicled and discussed not long ago for the same prognostication. No matter about dates; they are not to be given; but facts may be. This glorious country, free as it is, will not long be calm: Unrest is the word for this cycle. The people will rise. For what, who can tell? The statesman who can see for what the uprising will be might take measures to counteract. But all your measures can not turn back the iron will of fate. And even the City of New York will not be able to point its finger at Cincinnati and St. Louis. Let those whose ears can hear the whispers, and the noise of the gathering clouds, of the future, take notice; let them read, if they know how, the physiognomy of the United States, whereon the mighty hand of nature has traced the furrows to indicate the character of the moral storms that will pursue their course no matter what the legislation may be. But enough. Theosophists can go on unmoved, for they know that as Krishna said to Arjuna, these bodies are not the real man, and that “no one has ever been non-existent nor shall any of us ever cease to exist.”

Judge must have felt emboldened, if not vindicated in his predictions. On May 4, 1886, concurrent with the release of the second issue of The Path, a bomb planted by Socialist agitators detonated at a labor demonstration in Haymarket Square in Chicago, Illinois. A fatal riot ensued known as the Haymarket Massacre, which unnerved the American people.

William Q. Judge.

~

On May 16, 1886, Purve’s factory went up in flames. Writing to the Carpenters on May 22, 1886, Sattay states:

Sixty men are thrown out of employment and the owner is entirely ruined […] The climate agrees with me; but the summer is a dull season at the South. Thousands are doing nothing.

PART III.

On May 29, Gopalrao shared a stage with Frederick Douglass at the annual meeting of the Free Religion Association in Boston, where he delivered a speech titled “What Is Lacking In Christianity.” Christianity, “of all shades and shapes,” according to Gopalrao, was “destitute of every noble attribute.” Gopalrao continued his condemnation on Christian missionaries in India in June with a lecture in Concord, Massachusetts. He would continue touring the Mid-Atlantic and New England with five proposed topics of discussion: “The Present Condition Of India,” “The Missionary Labor In India,” “The Religions Of India,” “The Social Manners And Customs Of The Hindus,” and “Buddhism Contrasted With Christianity.” Anandibai, who was grateful for the kindness and generosity of her Christian friends, was no doubt embarrassed by her husband’s provocative address. She was also beginning to display symptoms of an unknown illness.

~

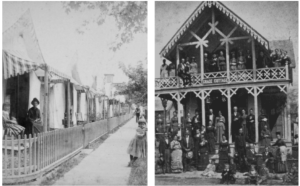

By the middle of June, Sattay arrived in Ocean Grove, just when the first Methodist “tenters” were arriving to their summer encampment. He soon found work in construction, building the new Engine House for the E.H. Stokes Hook and Ladder Company. It was a point of pride for Ocean Grove, as the municipality had recently purchased a new steam fire engine. With the exception of his turban of black silk, he wore the simple clothing of an American laborer, and lived in a shack near the construction site, across the railroad track just outside the confines of Asbury Park. Gopalrao soon rendezvoused with Sattay in Asbury Park, and proposed that his old friend give up his employment to become the manager for his lecture series. Sattay accepted, and successfully arranged several speaking engagements for Gopalrao in the hotel parlors of Ocean Grove.

(Left.) View of tourists in front of bath houses. (Right.) Grace Cottage.

~

As the Fourth of July advanced in Ocean Grove, “cottage and tent decoration became the order, until every flagstaff bore a star-spangled banner, and every dwelling was adorned with National emblems.” While the bells of the “tenters” echoed across Wesley Lake on Independence Day, Judge was in Rochester, New York, in the home of Josephine Cables, Secretary of the American Board of Control (of the Theosophical Society.) Judge and the leading members of the American Theosophists were attending the annual meeting of the Board of Control. Cables, in addition to her position as Secretary for the Board of Control, was the President of the Rochester Branch, as well as the editor of theosophical journal, The Occult World. In the coming weeks she would preside over a meeting which changed the name of the group from the Rochester Branch to the Rochester Theosophical Brotherhood, and host the first series of public Theosophical lectures, the inaugural meeting of which, it was anticipated, Gopalrao would lecture.

One notable member of the Rochester Branch was the social theorist, Matilda Joslyn Gage. In addition to her own notable achievements, she played an influential role in the life of her son-in-law, and fellow Theosophist, L. Frank Baum, the author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

Matilda Joslyn Gage.

~

In early July, while Anandibai was in Roselle, the Carpenters began to suspect that her illness was more serious than first believed. The Carpenters advised her to go to Delaware County, New York, where it was hoped that the fresh air would alleviate her symptoms. Writing from Delaware County on July 20, Anandibai told the Carpenters: “I am having chills three times a day, and fever. My whole body is aching.” When Gopalrao learned of this, he made arrangements for Anandibai to join him in Rochester, and postponed his lecture at Cables’ home. Before leaving New Jersey, Gopalrao instructed Sattay to remain in Asbury Park, and continue the lectures himself, to which Sattay agreed. Sattay quickly attracted attention wherever he could collect a group of listeners, and shared stories of his tradition and culture.

Among other statements was made this; viz., that Hindus worshipped the images which they, in fact, make of clay for memorial decoration upon certain high festivals, throwing them into the river when the day is over. Wealthy persons have images of gold for use upon such occasions; these are preserved, for, as Mr. Sattay used to say with his rare smile, “I do not think an American would throw a gold image into the river.”

~

On August 15 Gopalrao gave a lecture to a full room at the Rochester Theosophical Society. Once again, he criticized Christianity and the industrialized world. On August 19 Gopalrao gave another lecture in the rooms of the Rochester Theosophical Society. Anandibai was showing signs of a serious illness. Hoping, again, that fresh air would help her condition, Gopalrao and Anandibai left Rochester for Niagara Falls on August 20, 1886, and were joined by the Carpenters shortly after.

~

Back in Ocean Grove, it was reported in the newspapers, that Sattay was paid a visit by an unknown man:

A stranger appeared at the Grove in mid-August asking for Sattay, and said that he met him in New Orleans, where he had been stranded by missing his steamer for New York, and had appealed to this gentleman for a five-cent postage stamp for a foreign letter he had written. The gentleman had since heard that Sattay had come North, and was anxious to renew his acquaintance with Sattay. Later the two men were seen constantly together about the streets, and it was apparent from their conduct that they were more intimate than had been indicated by the stranger’s story.

With the assistance of Ellen C. Brooks and Martha Foster Inskip, Sattay was allowed to give his lectures in the rooms of many of the cottages and hotels. Martha Inskip, the widow of Rev. John Inskip, was instrumental in raising funds for the completion of a new building for the Calcutta Girls’ High School, and Sattay may have known her from Calcutta, as she was there with her late husband and a party of missionaries in 1880.

United States Hotel Main & Beach Avenues, Ocean Grove, New Jersey.

The lectures were essentially a religious forum where the differences between Hinduism and Christianity were discussed. Trouble arose when Sattay attended The 14th Anniversary of the Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society United States Hotel and addressed the ladies who filled the parlor. It was said:

[Sattay] denounced Christianity in terms of unaffected candor. He said that he was unfamiliar with the forms of English speech, and if what he said should offend the sensibilities of his hearers he begged them to believe that the fault was entirely due to his lack of understanding of our language and customs. He then launched into the most indecent and obscene tirade against the practices of American missionaries in India, causing consternation among the little congregation.

Sattay was then brought before Rev. Stokes, who invited him to attend his services. Sattay agreed, and found the meetings which he attended to be very interesting, but Dr. Stokes was determined to “argue him out of his religious beliefs and baptize him in the Christian faith.” When Sattay could not be persuaded, Dr. Stokes grew cold, and instructed Brooks and Inskip not to allow Sattay to deliver any more public lectures.

Ellwood H. Stokes.

Sattay continued to attend the Christian services at Ocean Grove, and when they were finished, he would stand outside the church. Many of the congregants, intrigued by Sattay’s Eastern clothing, approached him with questions regarding his beliefs and culture. Sattay answered their questions, and brief discussions on religion would develop. Whenever Stokes caught sight of this, he disbanded the crowd and ordered the women to return to their homes. When they would not obey, he would take Sattay by the arm and forcibly pull him away.

The Lake.

On August 18, 1886, the police forced Sattay into a boat, and sent him across the lake to the limits of Ocean Grove. Undeterred, Sattay returned the following day to attend the “camp-meeting like everybody else.” Upon his discovery, the police threatened to prosecute him for speaking to the people on the previous day on the grounds of “disturbance of peace and character.” Sattay ignored this threat and sat reading a newspaper on one of the benches near the Tabernacle. At 11 a.m. the police returned with a warrant, and took him into a police court near the association building. On the affidavits of two other officers, the chief of police, under order of Stokes, sentenced Sattay to thirty days in jail. He was immediately placed on the 4 o’clock train to Freehold, New Jersey, where the jail was located. The following day, August, 20, 1886, day Sattay wrote a letter to Gopalrao:

I am sorry to address you from a cell […] If you can see Dr. Stokes, I think you can procure pardon for me. Otherwise I must go through my thirty days. I have already passed two days. I am not at all disheartened. You need not be disturbed in your mind; but, if you are not going West with Dr. Joshee, I think you will do well to go to Asbury or Long Branch, and, if you can procure my pardon, we will never step into the limits of Ocean Grove any more. If even the streets and the beaches form a portion of their church limit, we have to conform to their rules. From my prison I will write letters to Dr. Stokes, Mrs. Inskip, and Mrs. Brooks, asking them to forgive my trespass, as God shall forgive theirs, as they ask in their daily prayer. I am sorry I did not take your advice of changing my residence. It is too late now. I have many sympathizers, but nobody knows I am in jail. It was done so suddenly and so secretly. Man must have all kinds of experience, and I am glad that I have this opportunity to learn how is the life of a prisoner. My conscience is not guilty. I have committed no criminal or civil offense. It is simply a persecution at the hand of an association that holds gospel in one hand and rod in the other. I am not ashamed to ask pardon, but I doubt whether Dr Stokes will grant it. There is no freedom in a Christian country. If we want to enjoy freedom, we have to be Christian, externally at least.

On August 24, 1886, The New York Tribune printed a short article about Sattay’s activities in Ocean Grove, stating that he “made himself obnoxious by making blasphemous utterances against Christianity. Sattay responded with a letter to the editor of the Tribune which said: “I shall feel very much obliged to you if you will kindly publish this, my letter, so that my sympathizers may know about it. I am penniless and friendless, and therefore I have no other help besides asking you to favor me. I beg to remain your obedient servant.”

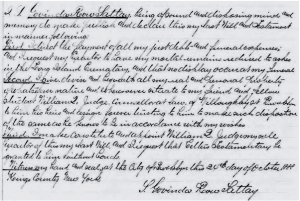

Later that day the warden of the jail, C.A. Little, who was out of town, learned of Sattay’s confinement. Having attended some of Sattay’s talks in Ocean Grove, Little was sympathetic of his prisoner and “characterized his arrest as an outrage.” Little sought the advice of a local lawyer named E.W. Arrowsmith, who subsequently discovered that the papers in Sattay’s case had not been filed. The following day, August 25, 1886, Arrowsmith, who volunteered to plead on behalf of Sattay, put the case before Judge Joel Parker who immediately ordered Sattay’s release. Little then gave Sattay some money, and sent him on his way. On the day that Sattay was released, W.Q. Judge wrote a letter to “S. Covina Row Sattay Esq,” in which he stated:

Your letter to Bro. Joshi has been handed me, in which you request his aid in getting you out of jail. While I sympathize with you, and shall try to aid you in this matter, and can see that the Association acted contrary to their supposed religion, I cannot endorse the wisdom of your proceeding which caused you trouble. No one is more opposed to Christianity than I am, but I fail to see by what right you invaded the premises of these people and gathered listeners round you without leave. That is not freedom; it is license. No missionary in India would be allowed to enter a sacred temple and propagate his religion or run down the other. He would be arrested by the authorities. This camp where you were, is for them devoted to their absurd religion, and you had no right to go there except quietly. Had you held your meeting outside in the road, they could have done nothing. Therefore you do right in asking their pardon no matter how wrong they are. I hope they will let you out. Legally I do not see any other way for the offense was no doubt committed. I am also sorry to see that you write Joshee that there is no freedom here unless one pretends to Christianity. Such a course is wrong and very unnecessary. The Vedas say that you must not revile the gods of other men. Karma often follows quickly on such an act. I like you violently oppose Christianity which is really very weak here, but I would be mad to rush into their places of worship and preach contrary-wise. But you tried in the one place where they are strong. I should be sorry to see you pretend to Christianity. If you do you will be reviled by these people; if you do not, you will have the respect and aid of the hosts of non-Christian people who are all over this land. Joshee spoke against the religion in Boston and was well received but it was in a hall where free speech prevails. I will go down to Asbury Park today and try to see Stokes and do what I can for you. I do not know where your things are but will try and find them.

Judge then went to Freehold to inquire about Sattay. Finding that Sattay had already been released, Judge then went to The Sun to have a story sympathetic to Sattay published. It said in part:

[Sattay’s] impression of the land as formed at Ocean Grove, he said, had given him a different notion now. Sattay, however, displayed a forgiving spirit, but he thought the Methodists erred in going about with the Gospel in one hand and the rod in the other. As nearly as can be learned, the only charge made against the young Hindoo was that in the stronghold of midsummer Methodism he had attempted to demoralize the people by inveighing against the Christian missions in his native land. It is at least apparent that the missionaries have not converted him.

~

During the events at Ocean Grove, the Joshees were dealing with the worsening condition of Anandibai. It was decided that they should leave Niagara Falls for Philadelphia, where Anandabai could receive treatment at the Woman’s Hospital. Arriving on August 28, 1886, they remained in Philadelphia for a few days, before Ramabai accompanied her home to Roselle.

~

On August 31, 1886, Judge followed up with another letter to “S. Govina Row Sattay,” in which he states:

My name, which you could not read is, Wm. Q. Judge. I am pres’t of the N.Y. Theosophical Society and one of the founders of the Society whose headquarters now are in India, at Madras, and I was there in 1884. I saw The New York Sun about your case and they put in an account, and now a Herald reporter wants to see you about it. I did not mean that you had disturbed their services or blasphemed but that you had committed sufficient offense for them as they own the whole of Ocean Grove and can exclude anyone they like. I thought you were injudicious for I know the temper of these bigots. Next time you will not be caught. In any public place you can say what you please but not in a place like that. You have sympathizers everywhere. I went down to Ocean Grove and found you had got out and gone away and was sorry I missed you. So I did the next best thing which was to fully ventilate your case in the New York Sun and it has now gone over the whole country. I will show your letter to the Herald man and perhaps he may put in some more which will give those people at Ocean Grove a good public flogging which they deserve.

~

Assuming that Sattay’s letter from jail to Gopalrao was mailed on the same day it was written, on August 20, 1886. That would mean that the letter made it to upstate New York, was read by Gopalrao (who was en route to Niagara Falls,) and then made its way back to Judge in Manhattan in five days. It is not impossible, but it is improbable, especially for the postal service in 1886. Let us speculate on another possibility by first examining a statement issued by Gopalrao at this time:

So far from the Theosophists approving of Mr. Sattay’s preaching Hinduism within the grounds of a Methodist camp meeting, a Theosophist warned him against staying in Ocean Grove, as he would very likely be imprisoned by the missionaries; which he was.