CONSCIENTIOUS CLERGYMAN.

JUNE 31, 1906.

Four months before the Mitchell hosted the Talks at The Benedick, Bishop Potter delivered a sermon in which he stated: “If the city rector doe not take his Summer vacation of three, four, six. or eight weeks…he will go mad or be will deteriorate into what his constituents least desire, a mere machine.” A reporter from The New York Times named “ION” interviewed Rev. Percy S. Grant to get his opinion on the statement. As it provides insight into the role the Church played in New York society during the Talks, I include it as an optional “exordium” to Mitchell’s work.

⸻

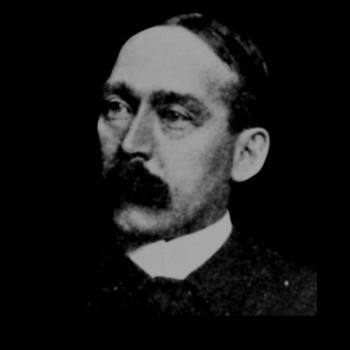

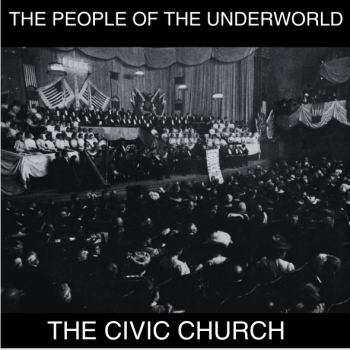

“You see,” said Grant, “times have changed. Twenty years ago, in all probability, Bishop Potter would not have laid such stress on the necessity for giving long vacations to the clergy of the city. But within those twenty years a complete revolution has taken place in the methods and kind of work that form the daily routine of the pastor of a metropolitan church. This revolution may be summed up in the suggestive phrase, ‘the socialization of the churches,’ a movement that began with Dr. Rainsford’s work in St George’s Parish. What does it mean? Simply that the church has entered upon a new and practical field of labor in which the mere preaching of pulpit sermons holds a very secondary part in the work of a pastor.”

“I told you that for the city pastor there are seven days of work instead of the five and a half that usually fall to the lot of the average business man. It may surprise you to know that those seven days the lightest burden of work comes to us on Sunday. In the old days—fifty years ago, say—Sunday was the one great day of work for the clergyman. Why is it different now? I can answer you best from my own experience, an experience that is typical, probably, of what comes to the majority of the clergy of New York.

The Church of the Ascension. (NYHS.)

“I find Sunday, then, the one day on which nothing is expected of me outside of the three services which I conduct and the sermons which I preach in the church. It is the one day when the clergyman is left pretty much to himself, notwithstanding the traditional notion that it Is his one’ day of work! What happens on the other six days of the week? Why, from the time that he gets up in the morning until he retires at night a city clergyman, even to the social side of his life, is occupied with his parochial duties, and this not in a desultory manner, but in accordance with a strict, methodical plan, such as you will find in every well-regulated business house.

“It is a little difficult to give you an illustration of this in the form of a schedule for a typical day, since a pastor’s workday is subject to variations incident to the variety of duties that come to us within the limits of every twenty-four hours. In my case, however, the daily routine is laid out pretty much in this fashion:

“At 9 o’clock in the morning a service of prayer is held in the church, one or more of the clergy officiating. At 9:30 there is a meeting of the parochial staff in the parish house, when we consult and pass upon special cases of distress, sickness, or want that call for attention in the parish. From 10 to 11 am in my office with my stenographer, attending to the correspondence of the parish and receiving visits from people the importance of whose business justifies their calling at that busy hour. Many of our societies hold meetings during this morning hour, at which I am expected to be present for as long a time as my office duties will permit. At 1 o’clock, luncheon. From 2 to 3 is my regular office hour, when, I am at home to all callers. From 3 to 7 committee meetings are held, parish calls made, besides the 5 o’clock service at the church. At 7, dinner. From’ to 10:30 in the evening I make a visit of inspection among the various parochial organizations.”

Grade-school class in a room at the Church of the Ascension with a nun, 1906. (Museum of the City of New York.)

“Where does the time for preparing the Sunday sermons come in?” asked Ion.

“Alas! as a matter of fact there very little opportunity left in the hurrying business of the day for this important duty,” said Grant. “Hence, it is usually after I have made my evening visits, when house and office are closed, that I find the quiet requisite for sermon writing.

“In the Lenten season, of course, all these duties are increased, and extra services are held in the church, at which a greater number of the clergy are required to be present. The daily Lenten services, also include preaching as well the regular services of prayer. The two regular daily services in the church are held throughout the year, except from June to October.

“The first seven years of my ministry were passed in a manufacturing town. There my vacation was from ten to fourteen days, during which time I paid someone to take my place in the pulpit. Here in New York I am given a vacation of two months by the vestry of my church. I have rarely been able, however, to take the full amount of vacation allowed me—that is, in the sense of being absent from the city for two months. Nominally I spend my vacation in my country home, forty miles from here. In actual practice, that means that I am in and out of town everyday, sometimes, during those two months looking after the affairs of the parish. For the thirteen years of my ministry in the Church of the Ascension I have only once been out of the city between the months of October and May, except on an occasional mission for the parish and once to Washington for three days on a personal matter. The one Winter vacation I took was a trip to the East several years ago with Bishop Potter.

“In New York a clergyman’s calendar of engagements is filled for months ahead with preaching, lectures at various institutions, and other activities that cannot easily be classified. In fact, by meeting the fair and proper demands arising from his position, the clergyman finds himself surrounded with a wall of duties that quite prevents his leaving town on any pretext. Many of these imperative engagements, too, are made for the Summer season.

“You see, a clergyman in this city, especially if he is at the head of an active parish, is the constant recipient of scores of personal appeals, most of which call for investigation and action. There are few outside of our profession, I imagine, who realize the many different kinds of people in this great city who look to the clergyman for sympathy and co-operation as they look to no one else; not even to members of their own families. It is this daily personal appeal, this touch with every variety of the human problem, that never ceases and is capable of keeping us quite as busy in August as in January. Our institutional work, the characteristic activity of the socialized church of modern times, is done mainly between November and May. But you would be surprised, nevertheless, how much of it goes on when the parish and the pastor are supposed to be on a vacation!

The Rev. Percy Stickney Grant.

“There is a nervous strain in all this, a strain that is inevitable and that is not relieved, as happens with other professions, by that weekly day of rest which the Hebrews knew so well was the basis of a healthy development. This incessant work that I have indicated is not the only, or even the greatest source of strain, however. You have seen from a typical day’s routine how little time there is for the preparing of sermons. Nevertheless, the clergyman is bound to keep in touch with the literature and scholarship of the day in order that his formal addresses may have both the form and substance that a public, growing more and more critical in such matters, demands. His hearers, he may be sure, are making a mental comparison of the thought and style embodied in his sermon with similar qualities in the last magazine article, the editorial leader, the newest book. Fifty years ago there was not so much of this critical spirit, for the simple reason that literary culture and scholarship were then not so general, the standards of comparison not so numerous or accessible to the masses. Now, however, the clergyman who is animated with the desire to express the soul that is in him with effectiveness is obliged to find time among his other arduous duties for extensive reading and writing.

“Let me give you an instance of the necessity for this kind of all-around literary equipment. I have Bishop Potter to make three public addresses in one evening. On the occasion of each address there were other speakers, and all of them specialists in the three different subjects considered. None of these subjects, however, as they were all secular, could be called specialties of the Bishop. Nevertheless, owing to the prominence of his position, his address in each instance, was expected to be quite as illuminating and suggestive as that of any of the other speakers—and this tax on his energy and versatility came at the end of a day, remember, filled with the routine of episcopal work in a diocese where from 400 to 500 clergymen are looking to him for help in the various problems of their parishes.”

“Why is it that clergymen so often go to pieces physically?” Ion asked.

“It is not merely because, under the new conditions surrounding our work, we have so many more duties than formerly. The doctor, probably, has as many and as continuous hours of work, unrelieved by stated days of rest as the clergyman—but he has not quite the same amount of emotional strain. The latter comes to us partly, no doubt, from the conducting of religious services, but more often from the peculiarly intimate personal relation the pastor maintains with each of his parishioners.

“All of a doctor’s work is, in a way, exact, following definite impersonal laws and resulting in certain known effects. The doctor need not worry over an operation, or the administration of a drug, or the prescription of a dietary regimen, since all these things are done by rule, sanctioned by long professional usage, with the personal equation practically eliminated. The clergyman, on the other hand, has to listen and minister to cases for whose alleviation there is no absolute precedent. Such cases are the thousand and one forlorn hopes, the troubles of soul and mind, the many complicated relationships, the sins, the poverty, the misery, that humanly speaking, are not always susceptible to cure, but which demand the pastor’s attention and his best efforts. If we could only write out a prescription for the woman who has lost her husband, the son who is out of work, the daughter who has gone astray! But there are so many intangible difficulties and uncertainties to be solved in these matters, so many intangible difficulties and uncertainties to be solved in these matters, so many subtle cases involving spiritual tragedies, all coming to the rector for treatment and care, bringing burdens that cannot be lightened by art or surgery, it is natural for one to feel the nervous strain that, unless some timely respite intervenes, causes physical breakdown.”

“What do you do to keep your health?”

“Why, I have belonged for a number of years to an athletic club, and I am a firm believer in the value of regular physical exercise in a gymnasium; but really I have not been able, owing to the pressure of parish duties, to go to the club since last December. August, and September are supposed to be my vacation, however, and I hope I may find enough time, then, to take up the necessary physical training. It is this elaborate institutional work, forming the feature of the modern city church, that increases the duties of the rector so enormously and renders a vacation an imperative necessity for him. This work is bound to still further development since it is showing itself to be of the utmost usefulness in filling in the gap between the rich and the poor, creating an understanding between the classes, supplying many important social and ethical needs that are felt by the community. By this socialization of the parish, the church is rapidly becoming an important element in the settlement of those questions which some people think can be settled only by great political upheavals. But it is quite possible that this development of the institutional activities of the church will ultimately bring about something like a division of labor in the work of a rector of a metropolitan parish, some arrangement by which a greater degree of specialization, such as exists in a university, may be practiced than is the case at present—else the overworked clergyman will stand more in need of a vacation than ever.”

⸻

Exordium: Conscientious Clergyman.

Chapter I. The Nature of the Inquiry.

Chapter II. Christianity and Nature.

Chapter III. Evolution And Ethics.

Chapter IV. Power, Worth, and Reality.

Chapter V. Pragmatism and Religion.

Chapter VI. Mysticism and Faith.

Chapter VII. The Historian’s View.

Chapter VIII.Organization and Religion.

Chapter IX. The Theosophical Movement.

Chapter X. Signs of the Times.

Chapter XI. Has the Church Failed?

Chapter XII. Silence.

⸻

CITATIONS.

“Pastor’s Summer rest Necessary, Bishop Says.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) June 25, 1906.

ION. “Does A New York Clergyman Earn A Vacation?” The New York Times. (New York, New York) July 1, 1906.