SILENCE.

November 11, 1907.

On October 21, 1907, a year after the first discussion at The Benedick, a meeting was held for the purpose of reorganizing and formalizing the “Philosophical Club” at Columbia University. At the meeting in which Woodbridge was elected honorary president, a committee of officers was elected, and the topic of merging with the Ethical Society was discussed. Max Eastman debated “The Relation of Ethics and Metaphysics,” which Dewey summarized before the topic was opened for discussion. The following meeting was held on November 4, 1907, and Montague read a paper titled “A Definition of Religion.” A week later, on November 11, 1907, Mitchell delivered an address titled “Silence” at Columbia University’s St. Paul’s Chapel, which opened the previous winter. When comparing the contents of the address with the aims and goals of the esoteric section, the full meaning becomes apparent.

⸻

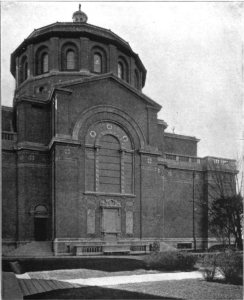

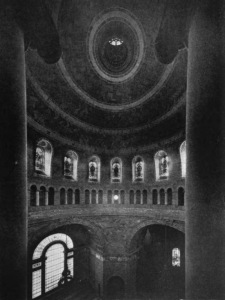

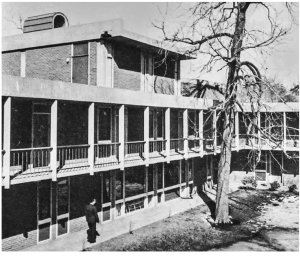

Exterior of St. Paul’s Chapel.

“It has become a truism—so universally has it been experienced—that every advance in civilization, every forward step of progress, brings with it its own peculiar danger and difficulty. There can be no increased possibility of gain that is not accompanied by an increased possibility of loss. If this be true of each stage or step in civilization, it is equally true of civilization as a whole, of civilization itself.

“Some years ago it was my fortune to travel in the nearer East. I remember one long day journeying through a Turkish province, where I saw no house or village, no sign of man, save one shepherd seated motionless above his flock among the Bithynian Hills. So still he was, so vast and still the scene of which he was a part, that the memory of its silence and its peace has remained with me. Day after day, I fancy, he so sat or walked alone—alone with his sheep on those wide sloping hills—master of their movements and his own.

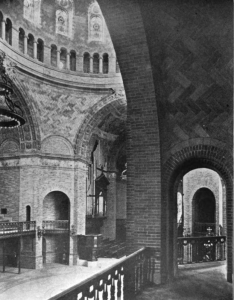

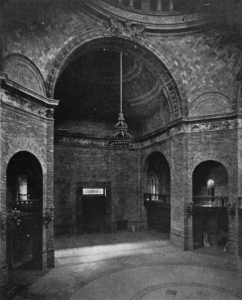

Interior of St. Paul’s Chapel.

“This university is a monument to all which that shepherd had not. It is a monument to the belief that man gains by contact with his fellows, that we can do together what no one of us could accomplish alone, that we may build our lives upon the united achievement of the race. Here are stored the age-long accretions of human knowledge. Here the best of the past becomes the heritage of the present, and here our own thought is guided and molded by the thoughts of others. Here, also, we are at the center of the life of the western world. Around us, in this city alone, throb the hopes and fears, the loves and hates, the ideals and aspirations of three million people. These, too, must be our teachers and our instruments. From them are liberated the powers by which the race must rise or fall. No man can measure their potency nor the possibilities that, through them, are ours.

Interior of St. Paul’s Chapel.

“But as we have gained so immeasurably in the possibilities for good, so also have we paid the price of greater risk. Here we are never alone. Here there is never silence. The voices of the past and of the present are ever speaking, ever flooding our minds with thoughts, sometimes high and sometimes low, but always—the thoughts of others. We do not act so much as we are acted on. In the midst of a myriad of distractions we have no time to be ourselves. We hurry ceaselessly from occupation to occupation, always absorbing, rarely giving. We live for and in reflections. We live in ceaseless turmoil—a turmoil of the thoughts and emotions, the passions and desires, the ambitions and strivings, of others. They surge over and through us and sweep us along with them to ends we never saw and never willed. Unconsciously we yield our wills to foreign motives and lose ourselves in the great currents of surrounding life.

Interior Of St. Paul’s Chapel.

“Across the centuries that separate us from that silent shepherd, from hills like his and his own Eastern land, there comes to us the question: “What is a man profited if he shall gain the whole world and lose his own soul? or what shall a man give in exchange for his soul?” To none is this question more pertinent than to us.

“The great message of Christianity is the infinite sacredness of the individual, of your being and of mine, of just that Inner meaning and will which is the Self. It can profit us not at all to gain knowledge, or popularity with our fellows, or success of any kind, if we lose ourselves in the process—if we become thereby the mere puppet or reflection of the life about us. Sacred to us beyond all else must be what we ourselves are. To voice this clearly and perfectly is genius; to abandon it is to abandon manhood itself. If civilization is to take it from us, then is civilization loss, not gain.

“Here is the danger which is the concomitant of our progress. Here lies the narrow way along which we must advance. We must learn from others, but remain ourselves. We must use the power of the world, not be used by it. We must guide our own lives by a will that is our own. We must be the master of our fate.

“We can do this only by constant vigilance; by deliberately forcing ourselves to look within, excluding for the time and by act of will all that comes to us from without. We must make for ourselves and within ourselves what we are denied in the outer world—a place of stillness and of silence. There, in the silence, at the bar of our own judgment we should question all that comes to us. There, in the silence, the learning of the past and the promptings of the present should be alike arraigned.

Interior of St. Paul’s Chapel.

“This is needful in our studies as in all else. The great thoughts of the past are of little moment to us save as they awake to consciousness that which is great also in us, and are claimed by us as our own. Our reading is a constant search and sifting for our own. And if the search be through the thoughts of others, the final sifting must be in the silence where the soul alone can speak.

“But still more necessary is it in our leisure and our play. Here there rise around us the many-tongued, clamorous voices of the city; the calls of our companions; the promptings of our appetites and passions. Take them one by one into the silence, and let the silence be their judge. Speak always, act always, from silence. Never agree to anything, never undertake anything, never speak and never act, until you have first taken both the motive and result into your inner silence, and seen whether it be indeed your own will that is urging you.

“Thus, and thus alone, will you be yourself. So, and so only, can you gain from civilization, and not be lost in it. So only can you learn to express yourself, and give to the world the one gift that is worth the giving, the gift of yourself—the gift of that unique spark of the Divine which you embody and which you alone can give. So only can you keep, or give, your own soul.

“This chapel is open from nine in the morning until six at night. Here, in such outer silence as this city affords, you may bring your doubt, your trouble, and your temptation; and, in the deeper and more sacred silence you make within yourselves, lay them before the Master of the Silence and your own soul. I think we will be wise to do so.”

⸻

Like its previous incarnation, The Philosophical Club lasted one academic year, holding its final meeting in May, 1908, the same month in which Talks on Religion was published. The success of the Talks would ultimately result in a more formal exchange of views published in Columbia University’s Lectures On Science Philosophy And Art (1908,) a series of twenty-one addresses delivered in 1907-1908. Contributions from Crampton, Robinson, Woodbridge, and Dewey were included. At the same time, Mitchell was nominated as Chairman of the Committee Instruction for college courses. In this capacity, Mitchell advised Nicholas Murray Butler, President of Columbia University, on the merits of a curriculum which included religious education. Johnston would describe Mitchell’s work in pages of Harper’s Weekly, stating: “The most noteworthy thing in the world today is the general revival of interest in religion…The fact next in interest and in promise and potency for the future is the renewal of the ideals of education in America.” Mitchell would continue to champion the cause of religious education throughout his tenure at Columbia. In 1911 Mitchell would deliver an address on the occasion of the commencement exercises in which he “pleaded for a broader education in the universities,” and expressed “the hope that the college education should stand for something more than the mere amassing of a certain amount of technical knowledge.”

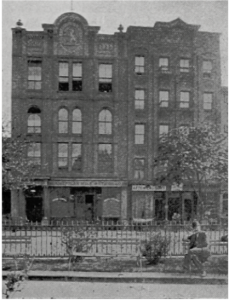

Chapel of the Comforter, 10 Horatio Street, New York, New York.

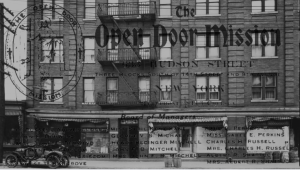

In 1910, Mitchell and the Theosophists had a falling out with Grant over a disagreement involving the activities of Alexander Irvine at the Chapel of the Comforter. When Irvine was removed from the pulpit, the inner group of the GTS , known as the Order of the Living Christ, assumed control of the operations of the Ascension mission. From that institution the OLC would develop the Chapel School, and the Open-Door Mission. In 1917, following the outbreak of the First World War, Mitchell would unite the efforts of his secular and spiritual vocations by assisting with the publication of both the Chapel War Papers, and the Columbia War Papers.

The Open Door Mission.

In the 1920s, Mitchell and the other members of the OLC opened and operated a spiritual retreat called Chapel Farm in Riverdale, Bronx.

Bungalow at Chapel Farm.

In 1953, after learning of H.N. Spalding’s Union for the Study of the Great Religions of the World at Oxford University, the OLC focused their efforts on creating a similar institution in the United States. Shortly before his death in 1956, J.F.B. Mitchell met with religious scholar Kenneth Morgan to enlist his aid in acting as a liaison between Harvard University and the New York Theosophists for a project that would ultimately result in Colgate University’s Chapel House, and Harvard University’s Center for the Study of World Religions.

Center for the Study of World Religions.

The deed of gift to Harvard is an alloy of the statement of purpose from the Theosophical Society, and the Union for the Study of the Great Religions of the World, the OLC expressed their wish for how the financial endowment should be allocated.

THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY.

The Society […] strives to create the nucleus of such a body. Many of its members believe that an acquaintance with the world’s religions and philosophies will reveal, as the common and fundamental principle underlying these, that “spiritual identity of all Souls with the Oversoul” which is the basis of true brotherhood; and many of them also believe that an appreciation of the finer forces of nature and man will still further emphasize the same idea.

UNION FOR THE STUDY OF THE GREAT RELIGIONS.

The great and richly diverse cultures of East and West—were to be studied and compared, in schools, universities, theological and other colleges and elsewhere, in their independence, integrity and fruitful diversity.

CSWR DEED OF GIFT.

The donors wish to encourage, in addition to a careful study of one’s own belief, a sympathetic study of other religions “in their independence, integrity and fruitful diversity.” The donors believe that such a study will show the extent to which there is a fundamental unity and reality back of all religions–a common root in the spiritual world—from which each man may gain a clearer insight and faith in the truth of his own religion.

Griscom would die in 1919, followed by Johnston in 1931, and Mitchell in 1956. In his will Mitchell stated:

I desire that my body be cremated and the ashes interred under the ledger stone which bears my name, with the other members of The Order, in our lot of The Order of the Living Christ in Woodlawn Cemetery, New York.

As per his request, his ashes were interred with the ashes of the six other members of the Inner Court of the Order of the Living Christ. (Ernest Temple Hargrove, Clement Acton Griscom, Jr., Genevieve Ludlow Griscom, Charles Johnston, Archibald Keightley, Theodora Dodge.)

Ledger stone for the Order of the Living Christ.

Marker for the Order of the Living Christ.

⸻

Exordium: Conscientious Clergyman.

Chapter I. The Nature of the Inquiry.

Chapter II. Christianity and Nature.

Chapter III. Evolution And Ethics.

Chapter IV. Power, Worth, and Reality.

Chapter V. Pragmatism and Religion.

Chapter VI. Mysticism and Faith.

Chapter VII. The Historian’s View.

Chapter VIII.Organization and Religion.

Chapter IX. The Theosophical Movement.

Chapter X. Signs of the Times.

Chapter XI. Has the Church Failed?

Chapter XII. Silence.

⸻

Citations:

King, Moses. King’s Handbook of New York City: An Outline History and Description of the American Metropolis. Moses King. Boston, Massachusetts.(1892): 519.

Mitchell, Henry Bedinger. “Silence.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. V, No. 3 (January 1908): 293-295.

Ancestry.com. West Virginia, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1724-1985 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015.

Original data:West Virginia County, District and Probate Courts.

“Chapel Farm: Another Endangered Landmark?” The Riverdale Press. (Bronx, New York) November 22, 1977.

“Chapel Farm’s Secret World.” The Riverdale Press. (Bronx, New York) March 27, 1986.

Higgins, Shawn F. “The Benedick: An Analysis of Talks on Religion.” Dewey Studies. Vol. VI, No. 2. (2022): 16-75.