THE HISTORIAN’S VIEW.

March 20, 1907.

Near the end of winter, 1907, Grant met the Socialist preacher, Alexander Irvine whom he invited to preach on Sunday nights at the Chapel of the Comforter, the mission of the Church of the Ascension. Not everyone, however, was as accepting as Socialism as Grant.

Helicon Hall c. 1906.

On March 16, 1907, a mysterious fire broke out at the Helicon Home Colony which destroyed the entire compound. Montague was among the injured, as The New York Times stated:

Prof. William Montague of Columbia University and his wife groped their way through the second floor to the court which they crossed, although the fire was then at its height, to reach the dormitory that they might make sure that their child had been taken out.

Fireplace at Helicon Hall c. 1906.

Montague was not the only injured member of the participants. On March 19, 1907, an unexpected storm brought “snow and rain, fog and slush and thunder and lightning to New York, all in twelve hours,” and was described as the “nastiest” of the season. Dickinson S. Miller, it seems, fell victim to the treachery of the ice, and “had a rather nasty fall which keeps him on his back.”

⸻

“It will be remembered,” said Mitchell “that at our last meeting Miller spoke to us of the origin, and meaning, of the religious sense; of the problem of evil; and of mysticism. The first of these he presented as rooted in the need of the human spirit to synthesize its environment, so infinitely wider than that of the brutes, and, in its trust in the One behind the many, to find support or relief from the prolonged reverberations of feeling which sweep over us from the mystery of life and from the vast impersonality of nature.

“The second—the problem of the existence of evil in a universe which we would believe ruled by good—could, he said, find a solution in the existence, not alone of good and evil, but of the better; which flows also from the nature of things, and shows us that life is not indifferent to good and evil, but sets in a steady current toward the good, the sense of which current we call the better. As we conform ourselves to this we are led to a deepening sense of trust and of love, which in their utter completeness constitute the experience of mysticism—the conscious union of the soul with that which is above and beyond it, and which is the consummation of religion.

“There was a fourth topic proposed,” Mitchell continued, “the place of the Church in the present age; but this Miller begged to postpone, so that what we actually considered was personal religion—religion as an inherent fact in the life of the individual.

“There is, however, another side to religion. Religion is also an historic fact; for around it have been built external organizations which have molded the life of nations and played no small part in the development of the race. I have asked Robinson to speak tonight upon the historic aspect of Christianity; for, as Christianity is closest to ourselves, it is through the historic development of the Christian Church that we can most easily trace the effect of organization upon religion, and it is this which I trust Robinson will make clearer to us.

“Will you not now begin, James, I think that all are here whom we can expect, as I regret to say Miller telephoned me an hour or so ago that he would be unable to come out tonight, having had a rather nasty fall which keeps him on his back.”

“The subject is such an immense one, and covers such a wide variety of topics, themselves complex, that to treat it at all intelligently would require not an hour’s talk, but a voluminous treatise,” said Robinson. “What I have to say, therefore, must be considered simply the headings for such a treatise, illustrated in one or two places by citations from the original sources; for these carry with them more of the atmosphere of the times than could be given by much description. Moreover they cannot be disputed, which is an advantage.

“In the first place we should have to consider the relation of the Church, as an historical institution, to its alleged founder. As one goes through the synoptic gospels to find out what Jesus actually taught, one is impressed most, I think, with the fragmentary character of it all. Our knowledge of Jesus’s teachings is confined to a year or two of his active mission, and even the brief record which we have of this is full of repetition and more or less obvious interpolations and later additions. For the most part, the synoptical gospels contain, besides the account of miracles, fragmentary moral advice suggested by the exigencies of the occasion, or in answer to questions addressed to Jesus by his followers. He speaks of love for God as our father, and for our neighbor; of gentleness, forgiveness, humbleness, and meekness. But it is needless to say that there is no trace in his teaching of the imposing theological, political, social, and cosmological systems which have been combined in historic Christianity.

“Thus the first chapter of our imaginary treatise might be devoted to showing that Christianity takes its name, but neither its organization nor its teaching, from Christ. Jesus did not contemplate the Church, I think. It was all a very temporary thing with him. Indeed, to the reader examining the gospels for the first time, and without any knowledge of the interpretation which has been given to them, it would seem that Jesus shared the opinion of his immediate followers that the end of the world was close at hand; all things were to be fulfilled before that generation passed away, so there was no need of an ecclesiastical organization, nor any time for one. Jesus conformed to the Jewish ritual, much as St. Francis did, in later centuries, to the Catholic; neither of them seemed to have thought of establishing a new religious sect. The possibility that his followers might become a rich and powerful order was, indeed, the nightmare of St. Francis’s existence, for he could look back to similar perversions of the spiritual life in earlier centuries. Jesus, however, could hardly have imagined the foundation of a Church; nothing could have been more alien to his life of religious enthusiasm and informal well doing than a scrupulously organized hierarchy. Our next chapter, therefore, would have to consider the origin and growth of organization and the establishment of the ecclesiastical hierarchy.

“Organization came in with Paul. In his epistles we have our first suggestions of an institutional history of the Christian Church. He mentions the ‘overseers’ and the elders and deacons, but does not define their functions very definitely. The overseer grew into the bishop, and the elders, who were evidently suggested by the elders of the older Jewish organization, developed into priests, subject to the bishops and offering up the body and blood of Christ at an altar. But the steps by which this transformation was accomplished will probably never be known to us completely, since the sources are too fragmentary to enable us to trace the change. Nevertheless, some data is obtainable, and the period of transition is relatively brief; for as we open the ‘Unity of the Church’ of Cyprian—who was the Bishop of Carthage about two centuries after the crucifixion—we find it already accomplished. The original democracy has passed away, and there is now a sharp distinction between the clergy ‘whose lot is in the Lord’ and the laity or people. Moreover, a still sharper line has been drawn between those who accept the ‘true doctrine necessary to salvation’ and those ‘enemies of God’ who venture to disagree in any respect. Heresies and schisms are the invention of the ‘Old Enemy’ of mankind who, now that he cannot keep men back in the darkness of the old way, entraps and deceives them in the new. Once the organization was founded, adherence to it and absolute acceptance of its teachings became immediately requisite for salvation. The concept of the one Church, embracing all ‘the elect,’ which was to remain the fixed and ruling idea of Christianity, and of every Christian sect, as far as one can see, had thus within two centuries completely overshadowed, if not replaced, the moral doctrines of Jesus. Here is a passage from Cyprian’s own hand—I read from his Unity of the Church—which shows how centrally important organization and conformity have become for him:

Whoever is separated from the Church is separated from the promises of the Church; nor can he who forsakes the Church of Christ attain to the rewards of Christ. He is a stranger; he is profane; he is an enemy! He can no longer have God for his father who has not the Church for his mother. If any one could escape who was outside the ark of Noah, then he also may escape who shall be outside of the Church…These heretics are plagues and spots of the Faith, deceiving with serpent’s tongue and artful in corrupting the truth, vomiting forth deadly poisons from pestilential tongues; whose speech doth creep like a cancer, whose discourse forms a deadly poison in the heart and breast of every one…

Though such a man should suffer death for confessing the name of Christ, his guilt is not washed away by blood, nor is the grievous and inexpiable sin of discord wiped out by suffering. He who is without the Church cannot be a martyr. He cannot reach the kingdom of heaven…Though they are given over to the flames and burn in the fires; though cast to the wild beasts, they lay down their lives, this shall not be a crown of faith, but a punishment of faithlessness. Such a man may be killed, but not crowned.

“Having given such account as our sources permit of the development of the church organization, it would be necessary next to follow its fortunes, and trace what was, in effect, the transition of the Church from a religious to a political institution. This would have to cover the periods in which Christianity was first opposed, then tolerated, and then accepted by the Roman Emperors; and should lead to an understanding of the position of the Church in the Middle Ages. For reasons which are not wholly clear, the government of the Roman Empire very early conceived a suspicion of the Christians, and from time to time its officials harshly persecuted the adherents of the new belief. It seems probable that they were regarded as turbulent, unruly fellows, brawlers and disturbers of the peace, seeking to overthrow the ancient religion and the ancient order, and so, of necessity, dangerous to the existent government. It must be remembered also that disrespect to the Roman religion was equal disrespect to the Roman Emperor, as Pontifex Maximus. It would seem inevitable that reflections upon this office should be resented and punished. The punishments, however, were clearly ineffective, and at last—to be exact, in the year 311, some sixty or seventy years after Cyprian—the Emperor Galerius, beset by political misfortunes and the ravages of a terrible disease, declared that the efforts to bring the Christians back to the religion of their ancestors had failed. Many of them consented, it is true, to observe the ancient customs, but as they persisted in their former opinions, ‘We see that in the present situation they neither adore and venerate the gods, nor yet worship the god of the Christians.’ The Emperor permitted them, therefore, to become Christians once more, and to re-establish their places of meeting. ‘Wherefore,’ the Emperor concludes, ‘it should be the duty of the Christians, in view of our clemency, to pray to their god for our welfare, for that of the Empire, and for their own; so that the Empire may remain intact in all its parts, and they themselves may live safely in their habitations.’ In short, it would seem as if poor Galerius felt that a certain amount of celestial electricity was being wasted and that it could not but advantage him and the Empire to encourage as complete an exploitation of heavenly powers as possible.

“In this edict of Galerius, Christianity is for the first time put upon a legal parity with paganism. Within a few years it had completely reversed the tables. Constantine formally accepted Christianity and actively interested himself in the Church. The first general council of Christendom was called together under his auspices in 325 A.D., and the religion which had been regarded by the earlier Emperors as a danger now became the bulwark of the state. The Christian clergy were successful in inducing the Emperors to adopt a system of strict intolerance. The ‘turbulent fellows’ were no longer the Christians, but those who differed from them. It was these latter who were now against the accepted forms, and so possible sources of trouble. Thus orthodoxy became a matter not only of religion, but of the state; and religious heresy was to be sought out and punished by state officials.

“The edicts issued during the next hundred years have, many of them, come down to us in the last book of the Theodosian Code. It is startling to see how completely the medieval church is sketched out in their provisions. An extract or two will, I think, help us to understand the temper of the times and the new relation of the Emperor to the Christian orthodoxy.

An edict of 380 declares that:

We desire that all those who are under the sway of our clemency shall adhere to that religion which, according to his own testimony, coming down even to our own day, the blessed apostle Peter delivered to the Romans, namely: the doctrine which the pontiff Damasus (Bishop of Rome) and Peter, Bishop of Alexandria, a man of apostolic sanctity, accept. According to the teachings of the apostles and of the Gospel we believe in one Godhead of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost; the blessed Trinity alike in majesty.

We ordain that the name of Catholic Christians shall apply to all those who obey this present law. All others we judge to be mad and demented; we declare them guilty of the infamy of holding heretical doctrine; their assemblies shall not receive the name of churches. They shall first suffer the wrath of God, then the punishment which in accordance with divine judgment we shall inflict.

“Orthodoxy and good citizenship have thus become identical. One who failed to accept the doctrine of Bishop Damasus, or suggested that the three persons of the Trinity were not alike in majesty, was not only to suffer the wrath of God, but the punishment which the Emperor should choose to inflict.

Eight years before an edict had ordered that those who taught the doctrines of Manes should be heavily fined; those who should attend a meeting of the Manichaeans should be cast out from among their fellow-men as infamous and discredited. The houses or dwelling-places in which their profane doctrines were taught should be confiscated by the government. A later decree declares that:

Clerics adhering to the Eunomian or Montanist superstition shall be excluded from all intercourse with any city or town. Should any of these heretics sojourning in the country attempt to gather the people together or collect an assembly, let them be sent into perpetual exile…

We command that their books, which contain the substance of their criminal teachings, be sought out with the utmost care and burnt with fire under the eyes of the magistrates. Should any one perchance be convicted of concealing, through deceit or otherwise, and of failing to produce any work of this kind, let him know that as the possessor of harmful books written with criminal intent he shall suffer capital punishment.

“The state not only intervened to defend the doctrines of the orthodox Church, it protected and granted it privileges; the clergy were to be exempt from taxation; the churches were to enjoy the right of asylum, as pagan temples had done. The clergy were permitted to try certain cases in which their own members were involved; and so we find in the Roman law the foundations of the vast jurisdiction of the Church and of the ‘benefit of clergy.’

“There is much that is surprising about the situation during the fourth and fifth centuries. Christianity not only becomes the state religion, but at the same time it unconsciously prepares itself to take the place of the state when that shall drop away with the dissolution of the Roman Empire in the West.

“But having traced the organization thus far, it would now be necessary to return and consider the intricate body of doctrine which had been forming during these centuries, and which explained the world and its history in the light of Christian theology. The theologians unconsciously drew their material from the widest range of sources—from the Hebraic tradition, from Egypt and Persia, from the philosophies of Greece. It would be very interesting to gather together the results of modern scholarship upon the sources of Christian belief; to trace the various streams from their confluence in Christianity to their rise in the separate national traditions and philosophies of many peoples; to weigh the influence of the North against that of Greece; to disentangle the Egyptian from the Chaldean. But all that concerns us this evening is to note that what became known as Christianity was not at all the teachings of Jesus, nor proceeded from a single source, but was first an aggregate, and then a synthesis, of the religious thought of the Mediterranean. Conceptions originally distinct and contradictory were molded into a seemingly homogeneous mass. The process of selection naturally involved a parallel process of rejection; and it is sad enough to see how much of that clarity which characterizes the reasoning in Cicero’s Nature of the Gods or in Lucretius has disappeared when we reach Augustine and Orosius. In considering this doctrine we must always remember that what we now look upon as poetic imagery, to be taken figuratively or symbolically, was for centuries regarded as literal fact, as literal as the most concrete data of chemistry or physics or astronomy.

“Santayana, in his Life of Reason, has given us a most instructive resume of the philosophy of history which the Church has for fifteen hundred years used its unrivaled power to defend. He calls it ‘The Christian Epic,’ a brief drama of things, and I do not think I can do better than to read certain passages therefrom, which, if we force ourselves to take them literally, will give us a very fair notion of what actually constitutes the Christian view of life.

“Santayana prefaces this account by a discussion of the human needs to which such a story appeals. Here he well says that:

The brief time and narrow argument into which Christian imagination squeezes the world must seem to a speculative pantheist childish and poor, involving, as it does, a fatuous perversion of nature and history and a ridiculous emphasis laid on local events and partial interests. Yet just this violent reduction of things to a human stature, this half-innocent, half-arrogant assumption that what is important for a man must control the whole universe, is what made Christian philosophy originally appealing and what still arouses, in certain quarters, enthusiastic belief in its beneficence and finality.

“But let me turn to the narrative itself:

There was in the beginning, so runs the Christian story, a great celestial King, wise and good, surrounded by a court of winged musicians and messengers. He had existed from all eternity, but had always intended, when the right moment should come, to create temporal beings, imperfect copies of himself in various degrees. These, of which man was the chief, began their career in the year 4,004 B.C., and they would live on an indefinite time, possibly, that chronological symmetry might not be violated, until A.D. 4004. The opening and the close of this drama were marked by two magnificent tableaux. In the first, in obedience to the word of God, sun, moon, and stars, and earth with all her plants and animals, assumed their appropriate places, and nature sprang into being with all her laws. The first man was made out of clay, by a special act of God, and the first woman was fashioned from one of his ribs, extracted while he lay in a deep sleep. They were placed in an orchard where they often could see God, its owner, walking in the cool of the evening. He suffered them to range at will and eat of all the fruits he had planted save that of one tree only. But they, incited by a devil, transgressed this single prohibition, and were banished from that paradise with a curse upon their head,—the man to live by the sweat of his brow and the woman to bear children in labour. These children possessed from the moment of conception the inordinate natures which their parents had acquired. They were born to sin and to find disorder and death everywhere within and without them.

At the same time God, lest the work of his hands should wholly perish, promised to redeem in his good season some of Adam’s children and restore them to a natural life. This redemption was to come ultimately through a descendant of Eve, whose foot should bruise the head of the serpent.

Henceforth there were two spirits, two parties, or, as Saint Augustine called them, two cities in the world. The city of Satan, whatever its artifices in art, war, or philosophy, was essentially corrupt and impious. Its joy was but a comic mask and its beauty the whitening of a sepulcher. It stood condemned before God and before men’s better conscience by its vanity, cruelty, and secret misery, by its ignorance of all that it truly behoved a man to know who was destined to immortality. Lost, as it seemed, within this Babylon, or visible only in its obscure and forgotten purlieus, lived on at the same time in the City of God, the society of all the souls God predestined to salvation; a city which counted its myriad transfigured citizens in heaven, and had its destinies, like its foundations, in eternity…

All history was henceforth essentially nothing but the conflict between these two cities; two moralities, one natural, the other supernatural; two philosophies, one rational, the other revealed; two beauties, one corporeal, the other spiritual; two glories, one temporal, the other eternal; two institutions, one the world, the other the Church. These, whatever their momentary alliances or compromises, were radically opposed and fundamentally alien to one another. Their conflict was to fill the ages until, when wheat and tares had long flourished together and exhausted between them the earth for whose substance they struggled, the harvest should come; the terrible day of reckoning when those who had believed the things of religion to be imaginary would behold with dismay the Lord visibly coming down through the clouds of heaven, the angels blowing their alarming trumpets, all generations of the dead rising from their graves, and judgment without appeal passed on every man, to the edification of the universal company and his own unspeakable joy or confusion. Whereupon, the blessed would enter eternal bliss with God their master, and the wicked everlasting torments with the devil whom they served.

“This is the philosophy of history which Christianity offers. Taken out of its setting of Biblical language, and without the anesthetic of accustomed phrase, this is the historic Christian doctrine, the explanation of existence which the Church not only has defended through the centuries, but for which it claims divine authority, and which it has sought to impose upon mankind under penalty of eternal damnation. I would ask you to supplement this picture of Santayana’s by another, a fifth century ‘symbol’ which has come down to us unchanged and is no more difficult of access than the English prayer-book. It is called the Creed of St. Athanasius. I shall not read it, though I have it here. It is, I presume, sufficiently familiar to you all. Historically it stands for the exaltation of mere correctness of formula; salvation by correct opinion in metaphysical abstractions. Such doctrine finds, of course, no support in the teachings of Jesus, to whom all theological subtleties were alien. The sin of confounding the persons and dividing the substance, of mistaking one uncreated and one incomprehensible for three uncreateds and three incomprehensibles was unknown to him. He surely never would have recognized the description of himself which the creed offers. One paragraph alone would he have understood—and they that have done good shall go into life everlasting; and they that have done evil into everlasting fire. But what we should especially remember is, first, that this creed is one of the most characteristic products of the Catholic Church, which was eagerly seized upon by the English Protestants and made the basis of good citizenship in the eyes of the state, as it had been made the basis of salvation in the world to come. ‘Furthermore, it is necessary to everlasting salvation that he also believe rightly…’ And, secondly, we must bear in mind that this body of metaphysical dogma is not treated as a relic of a bygone age, left, reverently perhaps, at one side by a living, growing Church, but is today the official creed, required to be said by clergy and congregation alike in the English Church, and there placed as the measure of human faith and religious thought, as the Nicene and Apostles Creed are in America. If today we interpret them symbolically rather than literally, it is through no permission of the Church, but in the face of its most bitter protests.

“But I must return to my outline,” said Robinson, “After tracing the origin of the Church as an institution, and the alliance between it and the state, after studying its theory of mankind and the universe and its interpretation of the past, it would be necessary before leaving this earlier period to speak of monasticism, which stood as a sort of monitor warning the Church against exclusive reliance upon administrative ability, political sagacity, and theology. In the West the contradictions between asceticism on the one hand and salvation through conformity and routine on the other were scarcely perceived. It is difficult to see why the monks sought personal hardship and suffered self-imposed penances when salvation was assured to them on easier terms. Monasticism was, perhaps, an instinctive protest against the supposed adequacy of mere correct belief and mere membership in the organization. The secular clergy never, as I remember, protested against the monks on general principles. Indeed, as has often been pointed out, the celibacy of the clergy was a distinct concession to monasticism.

“In judging the role of monasticism in the development of Europe, much would need to be said of the monasteries as occasional homes of culture superior to those which prevailed elsewhere, and of the activity of the monks, as teachers, as well as their economic role, which has been emphasized by Cunningham. We would have to deal also with that doctrine of St. Augustine, which identifies original sin with the attraction between the sexes, and which was made the basis of monasticism. This ungodlike, misleading, and devilish passion was put forward as the origin of all sin from the fall of Adam to the end of the world. The monk was engaged in getting woman out of his establishment and off his mind, so she naturally became for him the devil’s chosen instrument to lead him from the straight and narrow path. As Luther complained, the natural instincts underlying the family were viewed as something distinctly inferior, if not downright unholy. The influence of such teachings in degrading the relations between men and women must be obvious to us all.

“After dealing with monasticism, which in its origin belongs to the fourth century, that is, to the very time when those edicts in the Theodosian Code of which we have been speaking were issued, it would be necessary to take up the transition of the Church from its dependence on the still somewhat vigorous government of the Roman Empire to its practical supremacy in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, when feudalism constituted the only pretense of government which western Europe enjoyed. There is a growing conviction among scholars that it is safest, on the whole, to view the medieval Church as a state. As Maitland has very well said, the Church was organized like a state; it had its own law, its own courts, its own prisons; it collected its own taxes and possessed an elaborate financial and administrative system. If one were not born into the Church, as he was into the state, he was baptized into it before he could help himself; and everyone was assumed to belong to the Church in much the same way that we now assume that everyone belongs to the state. The Roman Catholic Church, then, was really the successor to the Roman Empire, and may be defined as an international and super-national state, imposed upon feudalised Western Europe.

The Pope not only claimed to be the over-lord of the Kings and even of the Emperors, but he was able to substantiate his claims in theory and not infrequently in practice. The Church was of divine origin, whereas the civil government was, after all, the invention of evil men instigated by the devil. This was well set forth by Gregory VII in a letter to Bishop Herman of Metz in 1081, apropos of the excommunication of Henry IV. Let me read you an extract from it:

Shall not an office instituted by laymen—by those even who did not know God—be subject to that office which the providence of God Almighty has instituted for his own honor and in compassion given to the world? … Do we not all know that Kings and princes are descendants of men who were ignorant of God, and who by arrogance, robbery, perfidy, murder,—in a word, by almost every crime, at the prompting of the prince of this world, the Devil,—strove with blind avarice and intolerable presumption to gain a mastery over their equals—that is, over mankind…

Furthermore, every Christian King, when he comes to die, seeks as a poor suppliant the aid of a priest, that he may escape hell’s prison, may pass from the darkness into the light, and at the judgment of God may appear absolved from the bondage of his sins. Who, in his last hour, whether layman or priest, has ever implored the aid of an earthly King for the salvation of his soul? And what King or Emperor is able, by reason of the office he holds, to rescue a Christian from the power of the devil through holy baptism, to number him among the sons of God, and to fortify him with the divine unction? Who of them can by his own words make the body and blood of our Lord—the greatest act in the Christian religion? Or who of them possesses the power of binding and loosing in heaven and on earth? From all of these considerations it is clear how greatly the priestly office excels in power…

Who, therefore, of even moderate understanding, can hesitate to give priests the precedence over Kings? Then, if Kings are to be judged by priests for their sins, by whom should they be judged with better right than by the Roman pontiff?

“The development of the Church into a state inevitably affected the attitude of the clergy toward their functions. Their acts were no longer personal and spiritual, but official and necessary, authoritative without regard to the subjective condition of the particular officer who performed them in the name of the mighty organization of which he was the agent. A demoralized clergy could now take refuge behind the doctrine of ‘the efficacy of the sacraments in polluted hands.’ This was never more insolently and instructively set forth than in an almost forgotten reply of a certain worthy Pilchdorf to the cavillings of the Waldensian heretics in the middle of the fifteenth century:

Since the sin of adultery does not take from a King the royal dignity, if otherwise he is a good prince who righteously executes justice in the earth, so neither can it take the sacerdotal dignity from the priest, if otherwise he performs the sacraments rightly and preaches the word of God. Who doubts that a licentious King is more noble than a chaste Knight, although not more holy ?—No one can doubt that Nathaniel was more holy than Judas Iscariot; nevertheless Judas was more noble on account of the apostleship of the Lord, to which Judas and not Nathaniel was called.

But thou, heretic, wilt say: “Christ said to his disciples, ‘Receive ye the Holy Ghost. Whosoever sins ye remit, they are remitted unto them’; therefore the priest who does not receive the Holy Ghost because he is wicked cannot absolve.” Even if a wicked priest has neither charity nor the Holy Ghost as a private man, nevertheless his priesthood is worthy as far as efficacy of the sacraments goes, though he himself may be unworthy of the priesthood…

For example, a red rose is equally red in the hands of an emperor or of a dirty old woman; likewise a carbuncle in the hand of a King or of a peasant; and my servant cleans the stable just as well with a rusty iron hoe as with a golden one adorned with gems. No one doubts that in the time of Elijah there were many swans in the world, but the Lord did not feed the prophet by swans, but by a black raven. It might have been pleasanter for him to have had a swan, but he was just as well fed by a raven. And though it may be pleasanter to drink nectar from a golden goblet than from an earthen vessel, the draught intoxicates just the same, wherever it comes from.

“This reasoning is exactly similar to that which would be used today in case one should appeal from the decision of a judge on the ground of his private immorality. The Church was forced into exactly the same position that the state is; that is, that the acts of an official are valid whether he be a saint or a sinner. To the earlier doctrines of the inerrancy of the Church’s views of God and man and the world, and the necessity of membership in the organization if one would be saved, was now added the necessity of accepting de fide the Papal monarchy, which included in practice its elaborate judicial and financial system.

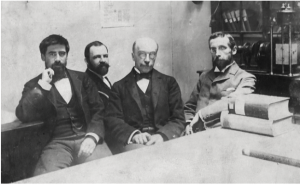

Professors, Department of History at the University of Pennsylvania. Left to right: Edward Potts Cheyney; Dana C. Munro; John B. McMaster; James Harvey Robinson.

The new era begins with the development of the national states, Aragon, England, France, and the inevitable conflict between the ever strengthening secular government and the international ecclesiastical government. The troubles fell into four main categories: First, how far was the King really subject to the Pope; secondly, how far could he tax the vast possessions of the clergy; thirdly, what classes of cases should be judged by the Church courts—especially, how extensive should be the appellate jurisdiction of the great central court of Christendom at Rome—lastly, how should the patronage in the Church be apportioned between the head of the national state and the head of the international state.

“It is impossible here to do more than hint at the problem which has faced Europe in the last five hundred years of outgrowing this most tremendous institution of the Middle Ages. It is not hard to see why the Church was ultra-conservative, was bitterly opposed to all progress, whether in the realm of thought or in the social order. Just as Burke, shocked by the course of the French Revolution, argued that nothing could be more dangerous than to examine the principles upon which the state rested, so the Church opposed any reconsideration of its claims. It showed a fatal sensitiveness to the dangers of scientific inquiry and political philosophy. It knew that it owed its power to an extraordinary set of circumstances, no one of which could be spared.

“In judging the attitude of the Church we cannot too often recollect what has commonly been the attitude of the state, for, after all, heresy in the Church is exactly parallel to treason in the state. It would have seemed as preposterous to Innocent III to have conceded that the Albigenses had a right to establish an independent religious community as it would to the justices of our Supreme Court if they were asked today to sanction a monarchy by the Grace of God, which some of us wished to found as an illustration of the inherent right of man to live under such government as he chooses.

“The powerful forces of conservatism, which were the inevitable outcome of the extraordinary system which we have been describing, suffered little change when the Protestant revolt came. The ‘Reformation’ may be described as nine-tenths conservatism and one-tenth reaction. To Luther, Melanchthon, and Calvin the suggestions of Copernicus seemed silly and wicked. While Luther was not hostile to social reform, the Church furnished him with a deficient set of canons of expediency and inexpediency; for example, the moderate demands of the peasants in the revolt in Germany in 1524-1525 greatly irritated him. Serfdom and slavery had existed from the first, and appeared to be divinely sanctioned. Should the peasants be granted their freedom, this would make ‘God a liar.’ The freedom of the body was in any case unimportant, since we should seek for true freedom in the spirit. In his reply to the peasants Luther makes the following judicious reflections:

There should be no serfs, because Christ has freed us all! What is that we hear? That is to make Christian freedom wholly bodily. Did not Abraham and the other patriarchs and prophets have serfs? Read what Saint Paul says of servants, who in all times have been serfs. So this article is straight against the gospel, and moreover it is robbery; since each man would take his person from his lord to whom it belongs. A serf can be a good Christian and enjoy Christian liberty, just as a prisoner or a sick man may be a Christian although he is not free. This article would make all men equal and convert the spiritual kingdom of Christ into an external worldly one; but that is impossible, for a worldly realm cannot stand where there is no equality; some must be free, others bond; some rulers, others subjects… I

f you will not follow this advice which God would approve, I must leave you to yourselves. But I am guiltless of your souls, your blood, and your goods. I have told you that you are both wrong [that is, nobles as well as peasants] and fighting for the wrong: you nobles are not fighting against Christians, for Christians would not oppose you, but suffer all. You are fighting against robbers and blasphemers of Christ’s name; those that die among them shall be eternally damned. But neither are the peasants fighting Christians, but tyrants, enemies of God, and persecutors of men, murderers of the Holy Ghost. Those of them who die shall also be eternally damned. And this is God’s certain judgment on you both—that I know. Do now what you will so long as you care not to save either your bodies or souls.

“With this cheerful and complete condemnation Luther leaves them to work out the cause of social progress as best they may. Indeed, it is not till three centuries later that the very moderate demands of the peasants are accorded them.

“If the Church was intolerant of social change it was even more bitterly opposed to all growth in knowledge. The advocates of the new were demented, inspired of the devil, or willfully perverse. This supposed necessity of denouncing science appears very early in the Church. Lactantius, a contemporary of Constantine, makes easy sport of those who maintain that people may live upon another side of the globe. In his Divine Institutes he says:

How can there be any one so absurd as to think that men can have their feet higher than their heads; or that in those parts of the earth instead of resting on the ground things hang down; crops and trees grow downward; rain, snow, and hail fall upward on to the earth? Who indeed can wonder at the hanging gardens which are reckoned as one of the seven wonders when the philosophers would have us believe in hanging fields and cities, seas, and mountains?…

If you ask those who maintain these monstrous notions why everything does not fall off into the heavens on that side, they reply that it is of the nature of things that all objects having weight are borne toward the centre, and that everything is connected with the centre, like the spokes of a wheel; while light things, like clouds, smoke, and fire, are borne away from the centre and seek the heavens. I scarce know what to say of such fellows who, when once they have wandered from truth, persevere in their foolishness and defend their absurdities by new absurdities. Sometimes I imagine that their philosophizing is all a joke, or that they know the truth well enough and only defend these lies in a perverse attempt to exhibit and exercise their wit.

“Leslie Stephen, I believe, has said that there is nothing like a theological training to destroy all intellectual diffidence. The Church furnishes an extraordinary example of this, as one traverses the long distance which separates Lactantius from Pio Nono; witness the latter’s reception of a supposed refutation of Darwin’s theory of evolution.

A system which is repugnant at once to history, to the traditions of all peoples, to exact science, to observed facts, and even to reason herself, would seem to need no refutation, did not alienation from God and the leaning toward materialism due to depravity eagerly seek a support in all this tissue of fables…And, in fact, pride, after rejecting the Creator of all things and proclaiming man independent, wishing him to be his own king, his own priest, and his own God,—pride goes so far as to degrade man himself to the level of the unreasoning brutes, perhaps even of lifeless matter, thus unconsciously confirming the divine declaration, “When pride cometh, then cometh shame.” But the corruption of this age, the machinations of the perverse, the danger of the simple, demand that such fancies, altogether absurd though they are, should—since they borrow the mask of science—be refuted by true science.

“But the Church, as we all know, has by no means confined itself to opposing scientific investigation; it has, down to the present day, consistently cultivated superstition and obfuscation in the supposed interests of an ignorant people. Our treatise would have to give a chapter to this heading, which should deal with miracle working by saints and sorcery by devils. For while originally the miracles attested the doctrine, later the doctrines attested the miracles. If the worker of wonders was opposed to the popular belief, then were his miracles proof of the agency of Satan. There would be no lack of illustrative material in any century, though perhaps one of the most instructive instances is recorded by Caesar of Heisterbach in his Dialogues.

Two men, simply clad but not without guile, not sheep but ravening wolves, came to Besançon, feigning the greatest piety. Moreover, they were pale and thin, they went about barefooted and fasted daily, they did not miss a single morning the matins in the cathedral, nor did they accept anything from anyone except a little food. When by this hypocrisy they had attracted the attention of everyone, they began to vomit forth their hidden poison and to preach to the ignorant new and unheard-of heresies. In order, moreover, that the people might believe their teachings, they ordered meal to be sifted on the sidewalk and walked on it without leaving a trace of a footprint. Likewise, walking upon the water, they did not sink; also they had little huts burned over their heads, and after the huts had been burned to ashes, they came out uninjured. After this they said to the people, “If you do not believe our words, believe our miracles.”

The bishop and the clergy, hearing of this, were greatly disturbed. And when they wished to resist the men, affirming that they were heretics and deceivers and ministers of the devil, they escaped with difficulty from being stoned by the people. Now that bishop was a good and learned man, and a native of our province. Our aged monk, Conrad, who told me these facts and who was in that city at the time, knew him well.

The bishop, seeing that his words were of no avail and that the people entrusted to his charge were being seduced from the faith by the devil’s agents, summoned a certain clerk that he knew, who was very well versed in necromancy, and said: “Certain men in my city are doing so and so. I ask you to find out from the devil, by your art, who they are, whence they come, and by what means they work so many and such wonderful miracles. For it is impossible that they should do wonders through divine inspiration when their teaching is so contrary to that of God.” The clerk said: “My lord, I have long ago renounced that art.” The bishop replied: “You see clearly in what straits I am. I must either acquiesce in their teachings or be stoned by the people. Therefore I enjoin you, for the remission of your sins, that you obey me in this matter.”

The clerk, obeying the bishop, summoned the devil, and when asked why he had called him, responded: “I am sorry that I have deserted you. And because I desire to be more obedient in the future than in the past, I ask you to tell me who these men are, what they teach, and by what means they work so great miracles.” The devil replied, “They are mine and sent by me, and they preach what I have placed in their mouths.” The clerk responded, “How is it that they cannot be injured, or sunk in the water, or burned by fire?” The demon replied again, “They have under their armpits, sewed between the skin and the flesh, my compacts, in which homage done by them to me is written; and it is by virtue of these that they work such miracles and cannot be injured by anyone.” Then the clerk said, “What if these should be taken away from them?” The devil replied, “Then they would be weak, just like other men.” The clerk having heard this, thanked the demon, saying, “Now go, and when you are summoned by me, return.”

He then went to the bishop and related these things to him in due order. The latter, filled with great joy, summoned all the people of the city to a suitable place and said: “I am your shepherd, ye are my sheep. If those men, as you say, confirm their teaching by signs, I will follow them with you. If not, it is fitting that they should be punished and that you should penitently return to the faith of your fathers with me.” The people replied, “We have seen many signs from them.” The bishop said, “But I have not seen them.”

Why prolong my tale? The plan pleased the people. The heretics were summoned. The bishop was present. A fire was kindled in the midst of the city. However, before the heretics entered it, they were secretly summoned to the bishop. He said to them, “I want to see if you have anything evil about you.” Hearing this, they stripped quickly and said with great confidence, “Search our bodies and our garments carefully.” The soldiers, however, following the instructions of the bishop, raised the men’s arms, and noticing under the armpits some scars that were healed up, cut them open with their knives and extracted from them little scrolls which had been sewed in.

Having received these, the bishop went forth with the heretics to the people and, having commanded silence, cried out in a loud voice, “Now shall your prophets enter the fire, and if they are not injured, I will believe in them.” The wretched men trembled and said, “We are not able to enter now.” Then the bishop told the people of the evil which had been detected, and showed the compacts. Then all were furious and hurled the devil’s ministers into the fire which had been prepared, to be tortured with the devil in eternal flames. And thus, through the grace of God and the zeal of the bishop, the growing heresy was extinguished, and the people who had been seduced and corrupted cleansed by penance.

“In traveling through France last summer and visiting Lourdes and Toulouse I was struck with the reluctance of the Church to let a single false idea go by the board. At Toulouse, where the Church of St. Sernin claims to have as large and potent a collection of relics as exist in the world, including the bodies of four apostles, I believe, and numberless martyrs who suffered under Diocletian and through the violence of the Vandals, here new tablets have been prepared which give with scientific precision the length of the saint’s bone in centimeters, suggest the malady for which prayers to the saint are peculiarly efficacious, and finally reassure doubters by means of a certificate of authenticity. The theological spirit is the same as it has always been.

“The inquisition I pass over. Though we hear much talk about it in Protestant circles, it was only a fairly efficient piece of machinery for stamping out heresy and enforcing the policies we have already discussed. Its cruelty is too well known to require comment.

“The chapter on superstition would bring our outline down to the present day. We would have touched upon the personal teachings of Jesus, and the thought of the times in which he lived. We would have seen that he could not have contemplated what Christianity so soon became—a matter of organization and of doctrine. We would have traced the building of this organization and its gradual growth and amalgamation with the Roman Empire, till, in the downfall of the latter, the Church remained its successor as a super-national state. Parallel with this we would have examined the sources of the Christian doctrine, watched the intermingling of their streams of influence, their conflict, and final crystallization despite their heterogeneousness. We would have seen how these two factors of organization and doctrine, with which Jesus had nothing whatever to do, replaced the personal teaching of Christ, and became the chief if not the sole means of salvation; and we would have come to understand the reasons why the Church clings so to superstition, and is so stubbornly resistant to all progress, so ultra-conservative and reactionary.

“All these things and many more would have to be considered in forming an estimate of the role which organized Christianity has played. Many, doubtless, feel that they must defend the Church on the ground that Jesus was responsible for it. This, as I have repeatedly said, seems to me a mistake. I think he can be completely exonerated from the many evils for which the Church has so consistently stood. The Christian Church did not owe its organization to Jesus, and no one would have been more disappointed than He at the results of doctrines attributed to Him. The great advantages and disadvantages of monasticism, and the wonderful role of the Church as a political institution, are, of course, very difficult to estimate. Such culture and such order as existed from the break-up of the Roman Empire in the West until the thirteenth century is certainly largely attributable to the Church; but from that time on, with the development of the state and with the development of science, the Church grows to be more and more a grievous anomaly.

“The final chapter of our work would be the most difficult of all to write or to treat in any adequate fashion. ‘What are we to do about it?’ is the question that would there have to receive consideration. We would have to turn from looking back to looking forward. I believe myself that we would have to seek a solution along two broad lines. The first consists in the denationalizing of the Church. That which was first against the state, became next imperial, then international, and then national. The Protestants were, as I have pointed out, extremely conservative; they could not conceive of a church as separated from the state, but they could conceive of a national as over against an international church. The Protestant principle was Cujus regio ejus religio. Certainly, as the Church has become national, it has lost many of the disadvantageous features of the medieval international church. But still more is necessary, and with the coming of the Separatists and Independents in England we have a new theory—that of voluntary religious association—which has been worked out with wonderful results in our own history; for churches with us are, of course, nothing more than religious clubs. What is taking place here is also taking place in France, and is, I believe, of vital moment to every nation, and above all to religion itself. When religion has ceased to have any association with politics, and has divorced itself from the social order, it will become a purely personal matter, as it seems to me that it should be.

“For the second line of advance I think we must foster science. It is upon science we must rely for the removal of crude superstition, for the breaking down of the barriers of ignorance and narrow prejudice, and for the lessening of man’s superlative conceit. If we can do these two things, then I think there is hope that religion may cease to be an impediment to social and scientific progress, and that its benefits, as its solaces, may be obtainable at less cost to the individual and the race.

“I fear I have talked too long,” said Robinson, “and in a rather desultory fashion. I know there is nothing particularly new or unfamiliar in the facts I have presented. Yet, in such discussions as we are conducting, these facts cannot be neglected. I have, therefore, wanted to put them before you in sequence, that some sort of connected notion of them might be reached. Fragmentary and one-sided as such a sketch must be, it is instructive; and it was scarcely possible to say what I wished in briefer compass.”

“I feel, James, that we have all to thank you very heartily,” said Mitchell. “I suppose, as you say, most of us were at one time or another acquainted with the main facts of this history, but it must be an unusual achievement to have made such an extensive outline so graphic. Moreover, the object of these meetings is to re-examine familiar facts, if possible, from new standpoints, in the hope that thus their very familiarity may cease to blind us to their significance. Here, therefore, is the problem you have set us: What is the significance of this record? The facts themselves cannot be disputed, but how are they to be interpreted? What elements here pertain properly to religion? What to raw human nature? You have shown us failure, superstition, narrow dogmatism, bigotry, and cruelty. You have dwelt upon the substitution of the letter for the spirit, and of temporal power for the Kingdom of Heaven. Is this sad record, then, properly a religious document? Or is it a psychological document, revealing the action of ignorance, intolerance, and self-seeking, as would the history of any organization whatsoever? If we were to trace the history of government, or of the very principles of consolidation and organization themselves, would we find a different record? These are some of the questions your account must raise, and which I trust we may consider. For my own part I would, at the beginning, attempt to defend the view that these ‘crimes committed in the name of Christ’ are properly ascribable neither to religion nor to organization as a principle, but rather to those promptings and passions of human nature with which the religious spirit must contend, and which have from time to time dominated the church organization as they have all other human institutions.”

“That does not tell us very much, does it?” said Robinson, “and another trouble is that the Church is entirely unwilling to be regarded as a human institution.”

“It may be that the word ‘church’ is used in two senses,” said Mitchell. “That of which you have traced the history is plainly very human, indeed, and whether it is willing or not, we shall have to recognize it as such.”

“I was, of course, speaking of Christianity as an historic fact—as the Church of history,” replied Robinson.

“That is the trouble with discussions on religion,” mused Dewey. “We never know whether we are supposed to discuss religion as it is, or as it ought to be.”

“It does not seem to me that that is the trouble here,” Mitchell confessed, “I think we have arrived at a fair notion of the religious attitude and spirit, but in the history of the Church we find this spirit seldom animating, or rather, seldom governing, the external organization. Its place was usurped by superstition on the one side, self-seeking on the other. Now, in order for religion, or anything else, to be effective in the world some type of organization is obviously necessary. The quest—”

“—Pardon me, Henry,” interrupted Dewey, “but why should organization be necessary to religion any more than to poetry?”

“Surely even poetry needs organization,” replied Mitchell. “A poem becomes effective only as it is known. To make it known there is need of organization—of the publisher and bookseller, and of what is, in fact, a very complicated mechanism.”

“Your argument is more ingenious than sound,” said Dewey. “Publishers are somewhat more recent than poetry.”

“But,” Mitchell replied, “is it not really obvious that for the dissemination, and even for the preservation, of any idea, or force, or method, organization is necessary? Long before the days of publishers, poetry still had its external organization in the bards and minstrels—save for which the early songs and sagas would never have come down to us. The more I think of it, the more poetry seems to me the epitome of organization, the most highly and rigidly organized of all forms of expression, its value depending no less upon the perfection of its form than upon the truth of its meaning. I do not think we can seriously discuss the value of organization; but that the question is rather how to retain its effectiveness while eliminating its evils. The record Robinson has traced for us brings this problem clearly into view, and should, I think, help us toward a solution; for it should enable us to analyze the forces operative.

“Chief among these, I believe, is the tendency to look for support to the visible rather than the invisible. The tendency toward materialization, which causes us so readily to substitute adherence to the letter for obedience to the spirit. Jesus said: ‘He that loveth me not keepeth not my sayings.’ But, as Robinson points out, those who came later replaced this love by formal acceptance of a creed, and obedience by membership in an organization. It seems we have here something more fundamental than the common failing of losing sight of our ends in dwelling on the means. This last is undoubtedly accountable for much—though we would not conclude therefrom that we should have no means whereby to attain ends. But here I think we have the action of something far more universal. I mean the action of fear. Is not this at the basis of the formalization and the indoctrination of religion? We are afraid in the presence of existence; like children waking from nightmare, we long for something tangible, something visible, something we can lay hold of. For when fear comes, then faith is shaken and the inner sight obscured. Therefore it is that we seek external supports to which we may cling. We are afraid to trust ourselves naked to the law; to the words of the Master we remember, but no longer hear; to a love which seems to sleep blind to our peril. It seems to me that, if we had faith, creeds would be unnecessary; and that the first requisite in freeing organization from its evils is to have the courage to recognize it as an instrument, a means, not an end, something we use to make religion effective, not something we cling to for our own miserable salvation.

“Is not the history of the Church, when viewed in this light,” continued Mitchell, “the history of a struggle between religion and these elements of our nature which are essentially cowardly and self-seeking? I would much like to hear what James would say to this.”

“I could only repeat what I have already said,” replied Robinson, “that I am speaking solely of the historic Church—the historic institution. I would entirely agree with you that this has very little to do with what we would like to consider religion.”

“I fear I have been talking very vaguely and loosely if I have given the impression that I believe the Church has little to do with religion,” Mitchell admitted. “I would hold, on the contrary, that the spirit of Christ has never wholly departed from the Church that professes his name; but that too often this spirit has been left to flower in obscurity, while the high places and government have been usurped by cowardice and self-seeking. It is the old story of the money-changers in the temple. It is always they who sit at the entrance and who make the noise. The real worshipper is quiet, and we pass him by unnoticed—until we are in sorrow or in trouble. Yet genuine piety rarely fails to leave its record, and I suspect this is to be traced in unbroken descent within the Church itself…a thread of gold running through the sombre pattern we have seen…or a fire…ever present though unnoticed, till from time to time it blazes out in great conflagrations of reform. It is, of course, impossible to consider all sides of a question at once, yet I think we should bear in mind that there is this other side to the Church’s record—not so obvious, perhaps, but nevertheless there. Was it not Clem who spoke of this at our last meeting, wishing such a history would be written—the history of the Illuminati, of the Church within the Church? I probably have not his words correctly, but was not this his thought?”

“The ‘Church Invisible’ was the term I used,” replied Griscom, “and it seems to me to stand for a very real and potent thing, perhaps, if we could see a little more deeply, the most potent thing in human history. Yet, I confess, I have not the habit of associating this very closely with what James would call the Church. It has rarely been on good terms with the authorities or the organization. Nor, indeed, do I often think of the Church when I consider the teachings of Jesus.” Griscom paused, searching for an efficient metaphor to express his sentiment. “It is more of an instinctive and temperamental disregard than a matter of reasoning, for I quite agree with Henry that there is every evidence of the continuous presence of spiritual illumination within the historic body.”

“Why will you not trace for us this other history?” Mitchell asked. “I know you have been reading along these lines for years, and you could give us another side of the Church’s record”

“I have not Robinson’s power of summary,” said Griscom. “I have, it is true, been much interested in tracing the flow of mystic thought through the centuries, and noting its recrudescence in the last quarter of each. Springing up, apparently spontaneously, sometimes in one country, sometimes in another, it varies in minor details and in expression, but in essence it is always the same. This is what I referred to as the Church Invisible, the succession of Illuminati. But it cannot be called peculiarly Christian, for it has existed among all peoples and in all ages. Jesus revived this teaching; he did not originate it. Indeed, St. Augustine himself so says, for he tells us that what he knew as Christianity had existed from all time, and was but given that name when revived by Jesus. In the end of the eleventh century the chief mystical movement was among the Spanish Jews, where also was the greatest culture and learning of the age. It was largely through them that Arabic and Greek and Oriental thought were disseminated through the West, and I do not think anyone can read The Duties of the Heart, by Rabbi Bachye, without being impressed by its breadth, its wisdom, and its penetration, as well as by its genuine religion.

“But in the twelfth century we find it in Christian guise—in the teachings of Peter Waldo and the Cathari. In the thirteenth there were the Brethren of the Free Spirit, or the Beghards; while in the fourteenth we find Tauler, and Nicholas of Basle, and the Friends of God; as well as Thomas à Kempis and Suso and the German Mystics. The end of the fifteenth century saw, of course, the unrest preceding the Reformation, and the movement is somewhat harder to recognize; but there was a Chancellor of the University of Paris, Gerson by name, who seems to have led a genuine mystical revival which, I suspect, affected the Reformation more than is generally believed. In the sixteenth we again return to Spain, but now among the Christians, not the Jews. Here were Alcantara, St. Teresa, and John of the Cross. The end of the seventeenth century gives us Molinos, and Madame Guyon, and the Quietists, as well as Fenelon. The eighteenth is the prelude to the French Revolution; but there in France we find St. Martin and St. Germain and the recrudescence of Mystic Masonry, and in the north, Swedenborg—though he has always seemed to me more psychic than mystic. And finally, there was the revival of Eastern Mysticism, which we ourselves have witnessed in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, largely resulting from the work of the Theosophical Society, and the translation of so many of the Oriental Scriptures.

“Plainly much of this was outside the Christian Church,” continued Griscom, “and almost always opposed by it, being sooner or later persecuted as heretical. The succeeding organizations, each of which for a while exemplified and carried on the movement, seem soon to have degenerated, where they did not immediately disintegrate on the death of their founder. But the spirit of these movements and their teachings have endured unchanged—the same today as when Jesus taught, nineteen hundred years ago. That is to me the true Church, this moving spirit and those who embody it; but, as I said, I do not often associate it with the external organizations. One gets tired using the word ‘Church’ in a different sense from those who would appear to have the best right to determine its meaning. Remember also that by birth and education I am a member of the Society of Friends.”

“You lean, then, toward my view,” Dewey asked, “that religion has nothing to do with organization?”

“Not at all,” replied Griscom, “though I do not, myself, care for forms and ceremony, organization seems to me essential, though it must be kept fluidic. I know how useful the Friends have made theirs.”

“There is a difference between finding a thing useful, and finding it necessary,” said Eastman. “Opiates are useful, but if depended upon, they do more harm than good. Buddhism does not require organization. Why should Christianity?”

“It is a mistake to consider Buddhism unorganized,” Johnston corrected. “Its organization is plastic, but very real. It seems to me that we can liken the Church to a casket, much kicked about and ill-used because often in the custody of those who did not know its secret; itself broken and defaced, but still preserving intact the scroll of the law. It is the Church that has preserved the teaching of the Kingdom, even where it did not understand that teaching, and it is thus to the Church that we owe our knowledge of it today, just as to the Brahmins we owe the record of the mystery teaching of the Rajputs.”

“Does this mean more than the preservation of the written texts?” asked Dewey.

“Yes, I think so,” replied Johnston. “All our Scriptures come to us through a priestly cast, to whom, as you say, we owe the continued existence of texts. But with these texts there is handed down a body of tradition and interpretation—often at fault, often mistaken and misleading, but again precious beyond all words, the garnered fruit of ages of spiritual experience and aspiration. The value of such a body of testimony, confirming and elucidating the original teaching, is priceless, if we use it rightly. I mean as a guide to our daily living, not as something to which we turn our eyes in distant intermittent reverence, sterile and fruitless. I remember a very short and pithy description from the Katha Upanishad: ‘The son of Brig took and did.’ That is what we need to do with our religion. We need to take and do. That also seems to me the lesson taught by the lives of the mystics to whom Clem referred. In each case the emphasis was upon the will—upon living rather than professing.”

“Is not that the explanation of the whole history of the Church?” asked Montague. “The confusion between life and a theory of life—the belief that Belief brings salvation? If we grant this, does not all the rest follow as a matter of course?”

“That is my view,” said John. “We need to preach salvation by works.”

“Whatever be its explanation,” said Robinson, “it is a most disappointing record,—a terrible record to call religious.”

“I quite agree with you,” said Johnston, “and the more closely we study it the more terrible it is.”

“Do you not think so also, Percy?” said Robinson. “Do you not think that Christianity has been very disappointing?”

“From what point of view?” asked Grant.

“From any point of view,” Robinson replied, “as an effort to better man. Do you not think that it is all very disappointing? When you consider what it cost?”

“Disappointing, perhaps, to Jesus,” Grant replied, “but surely we cannot call it so. Look at what it has done. Your outline is so extensive it is misleading. You have had to leave out of account entirely what must be the most essential element in judging of any religious movement. This is the effect it has had upon the religious-minded man. Here is the actual history of religion, written from generation to generation in the lives of its worshippers. The medieval Pope, thundering anathemas, is not making the history of religion, but the history of war. The great current of religious evolution flows by, as careless of his denunciations as he is ignorant of its mighty stream.

“Consider the life of the religious man before the coming of Christianity,” Grant continued. “Go back to the Greek civilization, to its wonderful philosophy, its art and its poetry—but also its unutterable vices. Consider Sophocles, the poet, next to Shakespeare, who gives me the greatest inspiration and pleasure, and consider his life. Think of those nameless vices of Athens, not as practiced by the depraved and outcast, but put forward as the proper delights of the philosopher, and of the poet, of those who stood for the highest religious life of a people. Such a picture fills one with amazement, so far have we grown away from it. The thought of these practices now excites only loathing and disgust, and our whole civilization unites in outlawing the rare degenerates who have been guilty of them. It took Christianity a thousand years to stamp this out, but it has done it. Whatever else we have gained, religion and debauchery have been forever dissociated.

“Consider the facts. Look at human nature as it is and as it was. So far from being disappointing, I believe that, could we reconstruct the conditions in which Jesus taught, measure and analyze the forces of that time and people, see them all as they were, not as now we fancy them, why, then, I believe we could calculate with mathematical precision the whole course of Christianity. So many years of persecution, so many centuries of temporal power, so long a period of superstition and authority, so much metaphysical theology, so much subtle logic on misconceived premises—all these could have been foretold. All the horrors of the inquisition, all the retaliation of the Reformers, all the abuse of power and degradation of high office, all these, too, could, I believe, have been foreseen; the working out and purging of the race from its poison. The effect of Christianity upon the world might be considered, almost, as the mechanical problem of the resultant of forces—presenting inevitable conflicts and the appearance and temporary domination of all sorts of anti-Christian factors.

“Why will not you scientists who preach the conservation of energy apply it? Why will you not see that the forces acting in men’s minds and hearts must work outward to their inevitable conclusion. I can conceive of Jesus waiting through the centuries till this should have been accomplished, waiting and working for its accomplishment. And I can even believe that, whatever the human brain may have thought, the great Soul within foresaw all this from the beginning—foresaw the ages of misunderstanding before His mission would be fulfilled, before His spirit of love and of service would dwell universally in the hearts of those who profess Him, before He could ‘come again,’ no longer, perhaps, as a man among men, but as the Spirit of Man itself, animating and uplifting the race to knowledge of its Divine Sonship.”

“Do you really think our improvement due to Christianity?” Robinson asked. “I most willingly grant the world to be better than it was, but I can see no evidence that this has been brought about by our religion—which appears in history always as reactionary. I have talked tonight to no purpose if that is not clear. The new thing, morally, in our age is the feeling of brotherhood, of unity, of responsibility for the welfare of others—other classes and even other nations. This, I think, we have developed to a degree never before known in the world. To the Greek and the Roman, as to the Medieval European, the masses beneath him were scarcely human—their happiness, their lives even, of no consequence whatever. But the change from this does not seem to me due to religion, but to democracy and science; to both of which the Church has always been directly opposed, and which require for their true development a tolerance of individual view that the Church has never to this day adopted. Indeed, from the record, could we not say that humanity had bettered religion, rather than religion humanity? Does it not, for example, seem strange to you, as well as disappointing, that Christianity, adopted by Rome, should so immediately have transformed a tolerant community into an intolerant one?”

“I doubt if Rome was ever tolerant in our sense of the word,” Grant replied, “or as toleration implies—spiritual brotherhood. Religious toleration under the Roman Empire was, to a large extent, an instrument of diplomacy, by which the gods of conquered peoples, and their worshippers, might be rendered favorable to imperial dominion. The pantheon was little more a symbol of religious tolerance than were Rome’s foreign legions symbolic of brotherhood or political equality. When was Rome really tolerant? Under Nero?”

“Nero’s persecution was not from intolerance,” countered Robinson, “or not from any other intolerance than that of the Christians themselves. It was political. Indeed, it was anti-semitic. I think they got the Christians mixed up with the Jews. But I must not speak positively, for really we are entirely uninformed as to the actual conditions of the alleged persecutions.”

“Robinson has started two trains of thought at once,” said Mitchell, “and I would like to see each followed further. The first is the growth among men of what must be recognized as a moral and religious spirit—the spirit of brotherhood—though, Robinson holds, religion did little or nothing to foster it. Now, to this seeming paradox, I hope we may later return, so in passing, I would only suggest that its resolution may lie in distinguishing between the two uses of the word ‘religion.’ On the one hand we identify it with a spiritual force moving in the race. On the other, we confuse it with an external organization ruled by, and, indeed, composed of, very imperfect human minds and hearts. All forms, all organizations, all habits tend to conservatism; tend to remain unchanged while the causes which prompted them alter. Life is continually outgrowing its clothes, and, in religious matters, particularly, we confuse the clothes with the wearer. It seems to me that James’s picture tends rather to support than to deny Percy’s concept of the Spirit of Christ, waiting and working ceaselessly through the hearts of men, broadening them year by year, lifting them from their narrow misconceptions, compelling brotherhood. Or, as Miller put it, if I remember correctly, ‘the doctrine of the Holy Ghost approves itself as essentially true in experience.’ Something has bettered us. Something has made us more religious, brought us nearer to the spirit of Jesus and an understanding of His message. Whatever this force may be, it is surely a religious force, ‘whose end is righteousness’; working, truly, through science and through politics; through, I believe, every department of life; but for this fact the more, rather than the less, genuinely religious; genuinely of the essence of that for whose service the Church exists. The second line of thought concerns this question of intolerance, so foreign to Christ, so often, and so cruelly, exemplified in the history of Christianity. Indeed, intolerance and fanaticism seem more marked in Christianity than in any other religion, save, possibly, Mohammedanism. The linking of these two religions in such a connection suggests that a further explanation, beyond that mentioned by James, might be found in the peculiar type of monotheism they represent—or, perhaps more truly, in a misunderstanding of monotheism. That is an idea I should like to put forward for consideration.”

“What do you mean?” asked Griscom.

“This,” said Mitchell. “So long as a religion is frankly polytheistic a broad tolerance is easy. In a galaxy of gods it is easy to find place for one more. Perhaps you had not heard of him. He is not one of your gods. But he may, nevertheless, be a very worthy and powerful deity. The religions of primitive civilizations, where communities were isolated and life very little unified, were essentially of this polytheistic type. From polytheism to monotheism and monism there are two paths. The first consists in the recognition that behind diversity of form there is a oneness of essence, that all these gods are, as it were, but aspects of a Supreme Hidden Deity; that in worshiping them one is really worshiping Him or It. This path consists, in short, of the recognition of the One Behind The Many, and to those who follow this path, tolerance is also easy. It is, indeed, the very essence of their creed. They would not wish to change any man’s religious system. They would only seek to make him go more deeply into it. For the unity lies within.