ORGANIZATION AND RELIGION.

April 17, 1907.

“To put this evening’s subject in its proper connection with what has preceded,” said Mitchell, “it will be necessary to go back two meetings. You will remember that Miller, being then requested to open the discussion, gave us the choice of four topics, of which we promptly selected all. He complied so far as to present three of them, which formed a fairly connected sequence of different aspects of individual religious feeling. The fourth topic he begged to postpone till it could receive more adequate consideration. That was the ‘Place of the Church in the Present Age.’ At the following meeting, when we were unfortunately deprived of Miller’s company, Robinson traced for us the history of the Church as an external organization. Beginning with the statement that Christianity derived its name, but neither its teaching nor its organization, from Christ, the first part of his thesis was directed to showing what he believed to be the origin and growth of these latter. He pointed out that once organization and doctrine had been established, membership in the one and adherence to the other became necessary to salvation; so that their effect was to substitute conformance to the letter, for obedience to the spirit of the law and the teaching. The crimes of the Church, its superstition, bigotry, and cruelty, its self-seeking and opposition to all progress, its political, rather than its religious character through the Middle Ages—all these were dwelt upon and illustrated by writings and records of medieval Churchmen. Then, turning to the present and the future, Robinson raised the problem of how to better this, and sought its solution along two lines, first in the denationalization of the Church, putting it on a legal parity with a literary or scientific society; and, second, in the removal of superstition by the fostering of science.

“In thanking Robinson, I pointed out how admirably his paper instanced the very problem to which these meetings owe their origin, and the need of analyzing religious history and phenomena that we may distinguish between the action therein of religion itself and of those tendencies in us with which the religious spirit must contend. In particular, I dwelt upon the tendency to replace the spirit by the letter, to remove our attention from the end and fasten it upon the means, seeing in this tendency that which led to the gradual materialization and externalizing of all religion and the danger in all organization. I held, however, that organization of some sort was essential to effectiveness, that it was, in fact, essential to the continued existence of anything at all. So that our problem was how to preserve its effectiveness while eliminating its evil.

“Dewey disputed this view, seeing no reason to believe that organization was more necessary to religion than to poetry; to which I replied that it was necessary to poetry. There was some further talk upon this point, and upon the cause for the intolerance the Church so greatly fostered. But, I believe, we all felt that the one evening had not permitted a satisfactory discussion of such important problems. Percy, indeed, made the direct appeal that we should consider in what way those who work through organization should direct their efforts; how we could profit by the mistakes of the past, and how make best use of past achievements. These, then, are the topics before us this evening: What is the value of organization in religion? What is the place and function of the Church in the world today? And from these I hope we will be able to pass to a third: In what directions should we turn our efforts so that organized religion may be raised to a freer, purer life, its effectiveness increased, its evils eliminated? To this end I have asked Dewey to open the discussion, after which I shall call upon Miller, for, if I am right in my guess, his fourth topic should be complementary to Dewey’s view.”

“It may be complementary,” said Dewey, “but I am confident it will not be complimentary. Miller and I have talked of these things before. Indeed, I suspect many of you will find me too radical. Let me preface by a remark which may seem to stand apart from my proper subject, but which bears upon it. It is this: Religion is too often discussed as though it were a separate and isolated thing, with an independent existence of its own; while, in reality, it is not a thing in itself, but a relation in which things are; an attitude which must be taken by some one, or something, before it has meaning. To attempt to discuss this relation independently of that which it relates is to invite confusion. For the peculiarity of the religious relation is that it is the essence of what it relates. A coupling link may be viewed and studied quite independently of the car and engine it connects. But the religious relation is no such mechanical contrivance. The aspiration of each man’s heart toward God contains within itself all that is most truly that man, and what is most truly God. It is meaningless without these. So religion can only be understood as we understand man and as we understand God.

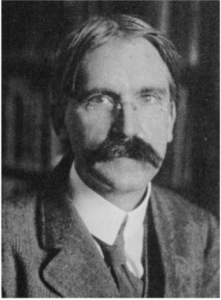

John Dewey.

“Now, I cannot pretend to speak of the development of religion from an anthropological or an historical point of view. I can speak only as a dialectician and consider the various ways in which the word has been used. Here I think we find three well-marked epochs or stages in the conception of Deity, or of that to which religion relates man. The first stage presents the primitive, tribal gods. In this, religion is not individual but communal. The correlate to which is that religion is without particular significance to the individual, concerning, in fact, only those portions of his life where his welfare is bound up with the welfare of his tribe. The god is the god of the tribe, treating the tribe as a unit and worshiped by the tribe as a unit. The sacrifices are propitiatory for the entire community, not at all individual, or expressive of an individual relation. Whatever relation exists between you and any particular deity exists because you are a member of a particular tribe which has either pleased or offended the deity in question.

“In the record leading us from primitive Judaism to early Christianity we see the transition from this first stage to the second. One God has been chosen from many, and that one has become supreme. But there remains the old tribal idea, that your relation to the Deity depends upon your membership in this or that body. With the Jews it was a racial matter; the whole Hebrew people were the chosen of God. With the early Christians, and perpetuated in Catholicism, it was a matter of membership in the organized Church. This was the hold and basis of authority. As Robinson pointed out at our last meeting, it was this special relation existing between the Deity and the Church which insured the salvation of all within the Church. So here, as in the first or tribal stage, religion still lacked the individual significance it was later to attain; and the concept of the Deity was still limited and provincial, still a God of one sect or institution more than of another.

“The most significant and essential thing in the Protestant movement, again speaking not as a historian, but as a dialectician, was the raising of its concept of God to universality. God was no longer the God of the Church alone, or even of Christendom, or of man, or of the whole world; but was actually cosmic and universal and absolute. So that man’s religion became the relation of man to the Absolute; the relation of that which is most completely individual to that which is most completely universal. Now, if this relation is universal, it can exclude nothing. It must exist between everything in the universe and that universe. It must exist between such a God and every man whatever his condition. It must be present in every act, every moment, every relation. No one organization can possibly confine it or make it exclusively its own.

“It is curious to note how often when men seek forcibly to alter a given condition they succeed only in re-establishing the content thereof in some new form or way. Again and again has this been proved in political history, where the tyranny of a king has been overthrown only to establish the tyranny of a mob; and it is equally marked in the history of ideas. Thus Descartes, who avowedly began by doubting all things, was led, through this doubt, to reaffirm all the essential elements of the system he sought to replace. Nor was Luther any exception. He but re-established, in different guise, and upon different foundations, the principles of exclusion and authority, logically so inconsistent with the broadening view of God for which he stood. It has happened, therefore, that Philosophy and Science have been left to champion what is actually the Protestant conception of Deity, and the universality and the immediacy of the religious relation. This conception makes quite untenable the claims of organized religion, which I have tried to show as survivals of the old communal or tribal worship. Therefore, I believe that there is no more place for organized, and so exclusive, religion in logic than there is in our own hearts. Religion must be immediate, personal, wholly individual, containing and expressing all that the man himself is.

“I go further, however, than thinking organization is simply unnecessary or superfluous. I believe it has been positive for harm—that the claim of the Church to be exclusively religious has greatly impoverished life and our other relations. In what is at once the wider and more personal concept of religion, which seems to me the true one, every act or moment of our lives must have its religious significance, which is the essence of that act or moment, its deepest and most sacred meaning, and in which we can see God. We have lost much by looking upon religion—our relation to the Divine—as something which is expressed through formulas and in the church. We have robbed the natural order of life of so much which it was meant to have—which it has, if we could but persuade ourselves to look for and find it in the daily round. Robinson alluded to the degradation of the sex-relations through the monasticism of the Middle Ages, but is not the effect of the Church today still to impoverish and belittle them? It truly has not killed marriage as an institution, but it has prevented it from reaching the development and the sacredness it should have reached. We are not taught to look upon sex-relations as sacred or holy. We smile at the worship of the lover. Often enough it is foolish and absurd. Nevertheless, no man who has felt real love but knows that in it the heavens have opened for him and he has come nearer to God. And love is but one of the innumerable aspects of life of which the same is true—which have been impoverished by this theory that religion is concerned with organization; for this leads us to look abroad for the sacredness which lies most close sat home.

“I would like to make my attitude clear on this matter,” continued Dewey, “and I do not know whether I have done so or not. If any one benefits by praying with others, or by any type of collective ceremony, I, of course, have no objection to offer to associations for such purpose. I suppose that seems very much like what organized religion now is. The word ‘organization,’ however, implies to me something exclusive, or as though a religious organization was in some way particularly or specially or exclusively religious, and this notion of confining religion I think very unfortunate and harmful. The word ‘association’ does not have for me the same connotations. But, as you know, I personally feel that religion is far too individual to benefit by such means. That, I hope, makes my general position intelligible.”

“It does not seem to me, Dewey, that your views are as radical as you made us anticipate,” said Mitchell. “If I understand you, you hold that nothing should stand between man and God. Religion being the relation of man to the Absolute, you argue that it must be direct and immediate as well as universal. The Church steps in and says intercourse is to be carried on through it and only through it. It wishes to be an assistance and intermediary, but succeeds only in being an added veil between us and the light, separating what should actually blend, and restricting what is universal. To such an organization of religion—which makes it a matter solely of an hour or so on Sunday, leaving the rest of the week free to be spent as we like—you distinctly object. For you show us that God can be found in every moment and act of our lives, and that if we do not so find Him in our lives they are wretchedly impoverished. To this we all must give assent, as we must to your final admission that you have no objection to ‘associations’ for worship or service if any find benefit therein. This seems to me a truer view than the other of the actual function of the Church. I think it was Crampton who suggested that religion was fully as much a matter of the consciousness of our relation with the Absolute as it was of that relation itself. We must surely all know the inspiration and fresh incentive that comes from companionship and tradition; and these, together with the reawakening of our religious consciousness, are services which religious organizations or ‘associations’ should perform for us. They should help us to be more truly religious at all times.”

“I would not agree that I needed any organization to help me ‘be religious,’” said Dewey. “It is little short of an impertinence, both to God and to me, for the Church to assume that I do.”

“I am again confronted with my old difficulty,” said Mitchell, “that I agree with others so much better than I can persuade them to agree with me. Evidently I ought to listen and not talk. Will not Dickinson give us his views now?”

“I ran over, so in my three topics at our last meeting that I have reduced to writing what I wanted to say tonight,” said Miller, “so that I might know just how long it would take me.”

“You know I told you the longer you spoke the better we would be pleased,” said Mitchell.

“It was very good of you,” said Miller, “I asked for ten minutes, and I do not think it will take me longer to read what I have here. Let me put it to the test. We have all of us at one time or another fallen on quiet days or hours and read for a while in the literature of counsel and ideal; it may have been in Marcus Aurelius, or, better, in Emerson, or, best of all, in Poetry. Has it ever happened to you to notice when the time had well passed and you were immersed again in work and society that there had been a change of mental weather; that you were now in a different and a heavier air, in which the animating ideas looked faded, and your spiritual energy had flagged? The question has but one answer, and on that answer rests the defense of the Church.

“For it is possible to keep oneself, comparatively speaking, in a certain atmosphere, and only too easy by negligence to wander out of it. We need to be brought back into the presence of thoughts and things that renew moral ardor or recall spiritual reverence. We need to be reminded. Now the Church is the great reminder. It says to us, I have called His ways to remembrance.

Dickinson S. Miller standing to the left of Eusapia Palladino (seated) during a séance in April, 1910.

“If you deliberately practice a new exercise, it may be riding or canoeing or some gymnastic feat, what is at first awkward and trying, the last thing you can naturally do, becomes, of course, if you acquire it at all, easy and spontaneous. We say this is because the machinery of muscle, nerve, and cell has been adapted to its task and the muscle has been strengthened,” Miller continued. “In point of fact, a new muscle has been made. There is not one department of power, art, science, humor, kindness, or social grace in which the like does not hold true. As the familiar French saying runs, the function makes the organ. There is a single word for this idea, the making of organs. It is ‘organization.’ Only we must not forget that in every case, as notably in muscle, nerve, and cell, it is not the making of a single organ, but a system of organs that are harmoniously to work together. And to create the organization within there must be brought to bear fit and unfailing agencies without—organs to build organs.

“The religious body that calls its teachings Christian Science protests that life and health do not depend on organs. When Christ healed, they say, he used no means; let us abjure means or machinery in general. These are not aids, but rather, if we put any faith in them, they are clogs upon the spirit, which only requires to wake up to its own free independence. Yet there is perhaps but one other Christian body that makes so persistent and masterly a use of the ecclesiastical machinery as they. (Hence, they are one of the few powers which that other body fears.) Their followers shall attend the services. The cured shall bear testimony before the congregation. The chosen passages from the books shall be conned and studied. The lamp shall be tended and kept burning. Is your health uncertain again? Do you seem to be overworking? It is because you do not give enough time to Science, that is, to the calm attendance or reading or contemplation that is enjoined. If anything goes amiss there is but a single remedy. You must come nearer to the Divine. And the ways are marked for you.

“This is only correct psychology or comprehension of human nature. John Stuart Mill is justly regarded as in great measure a disciple of Bentham, but Mill remarks that the religious teachers of the Church had a far deeper knowledge of the profundities and windings of the human heart than Bentham. The truth is that you do not gain men for a commanding idea, and mould them to it by making small demands upon them, but by making great demands. Unitarianism makes small demands, does not deem the Church very necessary, intimates that the chief thing is a wholesome civic and family life, correct habits, and good-natured feelings; accordingly, Unitarianism is the outer surface of the Christian religion, where evaporation takes place. We find something more to the purpose of life in Mrs. Gladstone’s simple remark that her husband conquered his irritability by years of daily prayer.

“In no case is this more clearly true than in the poetic interest. It is said, let religion be as free as the poetic sense. It is often quite as free and quite as evanescent. For the poetic interest easily atrophies. It completely atrophied in the hackneyed case of Darwin. But, also, it easily fails to develop at all. It is, of course, a frequent law of interests and instincts that, if not taken at their period of readiness, they wither and lose their responsiveness. Needless to say, all whom we call poets have heard or read poetry. Wordsworth tells, in the Excursion, of a man who would have written verse if he had had it about him in his youth. Nothing vibrates, nothing lasts, nothing carries its atmosphere and aroma from mind to mind and from book to mind more than verse; nothing can sleep more soundly in the brain when we let the stores alone. This is embodied in the homely saw, ‘Poetry is catching.’ Amongst gracious fostering traditions, rich with the spoils of time, encouraging originality while offering aid and added impulse, the tradition of poetry has a sure place. It does in some sort for a race what a parent of refined interests does for his children, when he carefully chooses his time to put Macaulay’s Lays, and Scott, and Byron, and Tennyson, and Keats, and Shakespeare, in their hands, and finds some means of inciting them to ‘keep up their poetry.’ A nation that read poetry more than ours and rewarded it with more appreciation, and on all sides criticized it by the standard of the best, would have a richer harvest than we. Perhaps one day American Universities will attack this fact. What poetry and literature, together with the whole element of tone and taste, flagrantly want in America, is criticism—our great lack—the preaching of standards, the organized bringing to bear of the best we know—a natural office of universities, journals, and voluntary associations, which should fill the atmosphere with it, that it might circulate insensibly.

“The word ‘voluntary’ recalls the idea of freedom so perplexingly invoked in this discussion. Is unorganized religion hampered because the organized exists? Need we care for Whitman less because we know the power of Milton’s measure? Are the woods and the mountain-top robbed of their awe because men build a house to God? Are we less prone to be moved by a chance sight of the sublime because we call His ways to remembrance every day? The truth is that the spontaneous warmth of sentiment that all prize, which can neither be confined nor loosed at will, is not a mere fragrance in the air, wafted hither and thither by an idle breeze. It rather is to be likened to the blooming of a plant with roots. It draws its vitality from the habit and spirit of the mind, and is easily sapped at a point below its level.

“Perhaps you will ask me what all this has to do with the actual Church of history, bound and barnacled with inheritances that obstruct the life of the spirit. On the abuses and infidelities of the Church it is tempting to dilate. No one of modern education will question that its dogmatic system, its form of organization, its legal and penal attitude toward faith, and much of its moral principle are from sources quite other than the precept of Christ—not wholly harmful for that reason. Christ framed no organization; he only brought a spirit and idea so potent that in the economy of human things they demanded an organization to perpetuate them. In a grossly imperfect manner they have been perpetuated. They are an everlasting gospel. He left his legacy amongst men. It had to survive (if survive it could at all) by taking the rougher, hardier, impurer forms that suit the mass of human society and by uniting for centuries with much that was alien to its essence. In so doing it also united with much that was sound and solid, though super-added to itself.

“But now the Church stands before us an immense fact,” continued Miller, “a broad foundation, halls where the people may be addressed, in a measure, habits of attendance and worship. It is daily widening its view, opening doors and windows. What a means for the stimulus and instruction of communities! Do you wish to see this enormous ‘plant,’ as the commercial phrase is, left derelict? Do you think that ardor for the ideal is already superabundant? Or do you wish to see men of critical and fastidious mind pass into it in greater force and leaven the whole? Perhaps you are not edified by its history. Well, fools build houses —yes, and knaves, too—that wise men may dwell in them. Perhaps you think that contemporary forms of worship, and contemporary preaching, are for the most part ill-calculated to nourish cultivated minds. Enter and modify them. The light and mellowness of the few must be imperfect, said Arnold, until the raw and un-kindled masses of humanity are touched with them too; those are the flowering times for spiritual things when there is a national glow of life and thought, when the whole of society is in the fullest measure permeated by it. In the Church, now gradually growing free and flexible, the most discerning criticism of life and the deepest kindling of the spirit might be at home. The rest must be brief. Christianity is social. The Mohammedan may pray alone in his mosque, and one Greek, or one Hindu, might sacrifice alone in his temple, but we gather in churches as a society. A man of cultivation says, perhaps, that he avoids church-going because he gains nothing by it. The truth is he gains nothing by it because he is capable of avoiding it as a poor bargain.

He has gone that he may be instructed and uplifted for the purposes of his life outside the walls. That is, indeed, a purpose of church service, but it is not the only purpose, and it is fulfilled only by passing chance, one might almost say, if the chief purpose be neglected. The service is not all an exercise about something else, about life, behavior, heaven, and the rest. It exists for its own sake. Where religion is real, I do not mean in every case or in every breast, there is a contagion and a common warmth, what we in other cases call the spirit of the thing, kept alive by observance, by singing, by prayer and rite and invocation. It is an experience, an enhancement of life, an infinitesimal portion of that communion in which religion culminates, social in its nature, and so not unfitted for the other end of binding men together as citizens of their common world.

“The life of the Church, rightly conceived, is a procession of symbolism. Now all life hangs on symbols. We perceive by symbols only, we think by their means only, our feelings cling to nothing else. Science is a system of human symbols and is anthropomorphic through and through. The same is true of art and religion. Now the continuity of any religion, the lasting gist and burden of its faith, is best committed to beautiful and venerable symbols, which stand while thoughts waver, and round which thoughts may safely work in unrestraint. Of such symbols, in spite of its sins, the Christian Church has been the one custodian.”

“Miller has said what I was trying to say,” said Mitchell, “only far better than I could have hoped to do. He has emphasized also the value of organization as an instrument—as a means of making our religious experience or aspiration effective in the world and of service to others. It is the effectiveness of organization which is its most salient feature. But before we enter upon a detailed discussion of Miller’s paper I would like to ask Charles also to speak upon the same theme, for I know him to have studied the Church organization from a very interesting point of view. Will you not repeat for us all, Charles, what you talked to me of the other day? Or put it as you will.”

“What I would rather say,” said Johnston, “would be in the nature of a commentary at once upon Dewey’s definition of religion, as the relation of the individual, or man, to the universal, or God, and also on the statement of Robinson, at our last meeting, that Jesus did not intend to form an organization. It seems to me we can get a good deal of light on the subject by seeing how the organization of the Church actually arose; by treating it historically, in a little greater detail than Robinson was able to do, having so much longer a period to cover. There is abundance of evidence on the subject and we have easy access to it.

“First, I take issue with Robinson in that I think it unquestionable that Jesus himself did establish an organization, and did so deliberately. Let us consider the early period of his ministry, especially as recorded by Matthew, an eyewitness of the early doings in Galilee.

“We have, first, the Baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist, from whom Jesus seems to have taken the rallying cry: ‘The kingdom of heaven has drawn near.’ Immediately after we have the Temptation, and then the first missionary epoch, in which Jesus visited the synagogues of Galilee, ‘preaching the gospel of the kingdom,’ declaring, in the words adopted from John the Baptist, that the kingdom of heaven had drawn near.

“The Sermon on the Mount, which immediately follows, sets forth this Gospel of the Kingdom: ‘Except your righteousness shall exceed the righteousness of the scribes and Pharisees, ye shall in no case enter the kingdom of heaven.’ This whole sermon is to be taken in connection with certain passages in the fourth Gospel, such as the conversation between Jesus and Nicodemus, where Jesus declares: ‘Except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God…Except a man be born of water and of the Spirit, he cannot enter into the kingdom of God.’

“We see, therefore, that the Gospel of the Kingdom was the doctrine that we must be born again, or born from above; that this spiritual rebirth follows on the death of egotism—‘He that would save his life shall lose it’—and that by this re-birth from above the soul is ushered into a new spiritual consciousness, the consciousness of ‘the realm of the heavens.’

“Both the Sermon on the Mount and the Sermon of the Last Supper make it clear that Jesus conceived this new consciousness as bringing the soul into direct and immediate relation with the Divine. In the former he speaks of the soul standing in the presence of ‘the Father who seeth in secret,’ and in the latter he says, ‘If a man love me, he will keep my words: and my Father will love him, and we will come unto him, and make our abode with him.’

“Therefore, we find Jesus teaching a new birth from above which ushered the soul into the realm of the heavens, where it held direct communion with the Divine, and also (and this is most significant) with the spirit of Jesus himself. It is quite clear that, if we contemplate a group of those who were thus ‘re-born from above,’ a group of disciples, their souls would stand in a direct interior relation to the spirit of the Master, and this would undoubtedly imply a new relation between these souls among themselves. This would be a sort of divine and necessary organization, flowing out of their common spiritual relation to the Master, and due to the driving power of the Master’s spiritual force, affecting them all alike. This is a vital side of the matter, to which I should like to return in a moment.

“Now, to take up the thread immediately after the Sermon on the Mount, we find Jesus, impressed with the thought that the harvest was plenteous, but the laborers few, organizing a vigorous propaganda, and sending forth his twelve disciples throughout Galilee and Judea, to preach that ‘the kingdom of heaven was at hand.’ He laid down a series of rules for their work, and thus undoubtedly established a preaching organization.

“This preaching order visited many towns and villages, especially in Galilee; and, at the same time, Jesus Himself continued His own propaganda, speaking in the synagogues, not only throughout the country, but also in the metropolis.

“To this vigorous propaganda, thus systematically carried out, was due the foundation of the central religious organization at Jerusalem, which continued after the Crucifixion; and a picture of which, with some embellishments, perhaps, we get in the early chapters of the Acts. Luke was not an eye-witness of these events, therefore his testimony here is not so striking in its vivid accuracy as it is in the later chapters, where he was personally present, with Paul. But we may rely on his account of the central organization in all its main outlines.

“Just such a preaching mission as we have already seen carried out by Jesus and his twelve disciples was later organized by Paul, and groups of students were formed in various towns of Asia Minor, and a little later in Greece and Italy, to study the teachings. We should note here that these groups were formed of students of certain teachings, and not exclusively of those who had been ‘ re-born from above,’ in the full sense. They met to study the sayings of Jesus, of which Luke speaks as being already written down; and also the letters of Paul, and later of Peter and the other apostles. We have an interesting survival of this in ‘the Gospel for the day,’ and ‘the Epistle for the day,’ which still form an essential part of the services of the Church.

“By a process entirely natural the older students had a certain weight and authority in these groups, and we find many references to them in the thirty years after the Crucifixion. They are called in the Greek presbuteroi, and women students of the same class are spoken of as presbuterai. These words are generally rendered ‘elders’—and we can see that they came to be looked on as a natural governing or directing body.

“In Acts: 20 there is a very interesting episode in which these elder students play a part. From Greece Paul had crossed over to the Asian shore, and was in port not far from Ephesus. He sent for the elder students of the group at Ephesus, and addressed them, bidding them take heed for themselves and for the flock, over which the Holy Spirit had made them overseers (episkopoi), and described to them the duties of their position, and the spirit in which they should carry it out. Then he bade them farewell, saying that they would see his face no more, and they saw him off on his voyage to Tyre.

“This was probably about the year 60. A few years later we find Paul laying down, for the guidance of Timothy, the qualifications of the overseer (episkopos): The episkopos ‘must be blameless, the husband of one wife, vigilant, sober, of good behavior, given to hospitality, apt to teach, not given to wine, no striker, not greedy of filthy lucre, but patient, not a brawler, not covetous; one that ruleth well his own house, having his children in subjection with all gravity (for, if a man know not how to rule his own house, how will he take care of the church of God?)’ and so forth. Writing to Titus, probably about the same time, Paul gives exactly the same qualifications for the episkopos, who is to be ‘the husband of one wife, having faithful children,’ and so on. These letters were probably written from Rome, a few months before Paul’s execution.

“Here is a perfectly natural organization: the groups of students in various towns, as the result of the vigorous propaganda already described; the elder students having a certain weight and authority, as was entirely natural; and the overseer or director (a married man with a family,) to guide and direct each group.

“We find Peter laying down certain most useful moral rules for the presbuteros and the episkopos, ‘The elders which are among you I exhort, who am also an elder, and a witness of the sufferings of Christ…’ Peter lays special stress on the principle of religious liberty, warning the elders and overseers (episkopountes) against ‘lording it over the flock.’ I have long thought that Peter is here quoting the words of his Master himself: ‘Ye know that the princes of the Gentiles exercise dominion over them…but it shall not be so among you…’The Greek word being the same as that used by Peter. Therefore, both the disciples of Jesus, and the students of the disciples themselves were specifically warned against that domineering spirit, that lording it over the flock, which worked such deep harm in later centuries.

“We saw that Paul indicated the father of a family who ruled his children well as a fit person to be an episkopos. It is easy to see how the paternal authority, the patria potestas, which was the foundation of early civil law, might color the mind of the episkopos, and gradually develop him into such a bishop as we see in the post-apostolic age. We can also see how the priestly idea might be added to the character of the elder student (presbuteros,) and, indeed, we can see the process at work in Hebrews vii, where Paul writes of Jesus as ‘a priest after the order of Melchizedek.’ It would be possible to trace the whole growth, step by step, till we came to the full-grown hierarchy. The preponderating influence of the world’s metropolis naturally gave a like influence to the episkopos at Rome, and thus we have the germ of the Papacy. The point is, however, that this organization grew up quite naturally among the students in various towns; and that we can see the intrusive elements gradually changing what was at first a free order into a despotism. The fault is not with the order, but with the intrusive elements, which must be extruded once more, as indeed they are being extruded in these latter days.

“To come back now to the point touched on before. We found Jesus speaking of the new birth from above, in virtue of which the soul of the disciple was brought into immediate spiritual touch with the spirit of the Master: ‘We will come unto him and make our abode with him.’ This was said on the eve of his death, and at a time when he was fully convinced that his death was at hand. But we do not find Jesus thinking of this relation, thus inwardly established between his spirit and the souls of the disciples, as about to be ended by his death; on the contrary, he clearly contemplates it as something to endure indefinitely, quite independent of his death. ‘I am with you always, even unto the end of the world.’[…] ‘Where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them.’ It is here clearly contemplated that the inner relation between the soul of the disciple and the spirit of the Master shall continue, quite independently of the approaching death of Jesus.

“I believe that we have an instance of the establishment of this interior relation in the conversion of Paul on the road to Damascus. The soul of Paul came into interior touch with the spirit of the Master on that occasion, and this interior relation continued throughout Paul’s life. Again, the relation already established between the soul of John and the spirit of the Master continued throughout John’s long life, and I believe the Apocalypse is a record, in part, of that conscious relation. The very strangeness of this thought is, no doubt, one of the reasons why the authenticity of the Apocalypse has been called in question.

Charles Johnston.

“I am convinced that John and Paul are only the first members of an unbroken series; that, side by side with the ‘apostolic succession,’ there has been a succession of saints, who have in their interior lives realized the ideal of Jesus, when he said: ‘Behold, I stand at the door, and knock: if any man hear my voice, and open the door, I will come in to him, and will sup with him, and he with me.’ This is exactly the ideal expressed in the Sermon of the Last Supper, and the same image is used for the spiritual communion.

“We have an unbroken series of witnesses to the truth of this promise. I need mention only a few, such as St. Columba, St. Francis of Assisi, St. Catherine of Siena, all of whom bore testimony to just such communion as that described by Paul and John. And I believe that to the spiritual power of these great souls, and many more like them, is due the spiritual power of the Church through the centuries. They were the salt of the Church; their spiritual power is the silver lining to the dark cloud of ecclesiastical domination.

“Thus, it seems to me, we have first the spiritual organization of the disciples, as taught and exemplified by Jesus; an order which is really continuous throughout the centuries. And we have, on the other hand, the organization of the disciples of these disciples, the students in various towns, with their ‘elder students’ and ‘overseers’ gradually developing into priests and in these latter days, it will once more become something as healthy, as wholesome, as humane as it was on the day when Paul took leave of the elder students of Ephesus, and launched his boat on the waves on his way to Tyre, and thence to Rome.”

“It could only be with much hesitation and many misgivings that anyone would attempt to summarize the three views of organization we have listened to,” said Mitchell. “Each contains so much of value, each differs so completely from the others in the view-point adopted. But, different as they are, they do not seem to me unrelated; and I believe that, however faulty must be the result, the attempt to exhibit their unity will be of value.

“Dewey begins by re-emphasizing the universality of religion—that the essence of all things is sacred, that God is to be found, and worshiped and served, in each moment and act of our lives; and that to the extent to which organized religion is exclusive, it is an obscurant and a barrier—impoverishing life, dwarfing religion, and obscuring God.

“Miller dwelt on the value and the need of times of attuning ourselves to the inner rhythm, in order that our relation to the universal may be one of harmony rather than discord; and that through this harmony we may become conscious of the spirit of life, whose universality I understand he would admit, but the consciousness of which is both too limited and too evanescent. He next passes to the efficiency of organizations, using the Christian Science regulations as an illustration thereof. It seems to me that Christian Science illustrates equally Dewey’s point, of the exclusiveness of formal religious bodies. For, though I object to much in Christian Science, much else is of value and appeals to a genuine need of the heart. But the churches have excluded it all from organized religion. Standing isolated and alone, as a separate ‘ism,’ the unfortunate elements have been emphasized, and where in proper relation it might have been wholly good it now seems fruitful also of harm. But that is not my theme. Finally Miller pleads that we view the Church not only for what it can give to us, but for what we can give to it, and through it to the world, recognizing that Christianity is social and that its forms are only symbols,—symbols such as are necessary to science as to religion, or to thought itself.

“Charley presents the Church organization as but the historic outgrowth, expression, or symbol of an actual brotherhood; of ties which are not matters of external forms but of inner fact. Those animated by a common purpose or ideal find that this fact acts as a bond between them whether they will or no. We see this among men of science quite as plainly as anywhere else. Those who are seeking the solution of the same problem find themselves drawn together in a tie which is often closer than that of blood. Much more is this true among disciples of the same Master. This, I take it, would be what Clem spoke of as the ‘Church Invisible,’ which the visible Church should symbolize. That it must include today many outside the ranks of organization is evident; so here, too, we would return to Dewey’s objection of exclusion in religious matters. Membership in such a Church as Charles has sketched must be a matter totally of our own interior attitude, the relation in which we put ourselves to the Christ spirit and ‘the will of the Father in Heaven.’ This is something it would seem necessary for the visible Church to realize if it is to be indeed Catholic, or symbolize truly the Inner Brotherhood of which Johnston speaks. Incomplete as this summary is, it will, I trust, serve to put all these views before us for discussion. The field is certainly both rich and wide.”

“I have to go in a few minutes,” said Eastman, “ but there are one or two things I would like to say first, if I may do so now. I have been thinking about what Percy said at our last meeting. You remember, Percy, you were speaking of how much the Church meant to you, and particularly prayer within the Church, so that you were sure your religious feelings could only be satisfied in organization. Now, I think that is unhealthy. I don’t think it is the normal, healthy thing to want to enter an organization or a church whenever you feel religious. Last Sunday I entered a church, and as I sat there the sun came in the window and a breath of air and some notes of a song-sparrow that must have wandered from the park. I felt religious, and I got up and walked out.

“Another thing,” continued Eastman. “Miller asked us whether the sun and the mountains and the beauty of nature meant less to us because we built churches; and whether regular religious practices made us less likely to be moved spontaneously by what was beautiful. I say yes, I think they do. If we associate acts of religion and religious feeling with certain times and environment, we tend to forget them at others. That is simply common sense. I don’t think of winding my watch until I take my waistcoat off, nor of the newspaper save at breakfast, nor of my slippers save in my own room. You attend to the news at breakfast and then comfortably forget about it until the next breakfast. And it is exactly the same with religion. If you associate your religious feeling with eleven o’clock on Sunday, you forget all about it from one week’s end to the next.

“Again, take what Miller said about making organs. As soon as you make an organ for a certain purpose you turn that function over to the organ and you yourself disregard it. You don’t think about digestion. You let your stomach do it for you. You only do what you have n’t an organ to do for you, and only think about it when the organ fails—when you have indigestion. I don’t remember much about the little biology I was supposed to learn, but I think there was some kind of a sea urchin or animal that, so long as it didn’t have any mouth or stomach, wrapped itself around its food and digested with all of itself. As soon as it developed a mouth and stomach, it let these feed for it. That is what I think happens when we organize our religious sense and feeling. We turn it over to something or other and cease to think about it. This is what I particularly wanted to say, and I am much obliged to you for letting me say it and run away. I wish I didn’t have to go. But I must. Goodnight to you all.” [see Max Eastman’s “The New Art of Healing” The Atlantic (May 1908)]

“As I have been holding down the safety-valve for two months,” said Crampton, “I find it difficult to refrain longer from entering again into the discussion. There is so much in what has been said upon which we may all agree that it may seem ungracious to bring up points of difference; but there are some matters that have been presented regarding which there may be, I think, at least two points of view. I think that zoologists are agreed now that function does not precede structure, as has been stated by Miller, in discussing the religious consciousness. If there is anything that modern experiment and observation have taught, it is that structure itself precedes the function, or, at least, the two are so combined that it is not correct to speak of one as coming first and controlling the other. And then, too, I find it difficult to believe that so purely individual a thing as the religious consciousness or function ‘necessitates’ organization at all, any more than a function of a lower order, such as digesting or seeing, necessitates a gathering together of men in order that each man may thereby facilitate digestion or sight. Take our luncheon room at the University. Pleasant as the conversation is, it certainly is not necessary for the purpose of eating. Indeed, it draws the blood from the individual stomach, where it is needed for digestion, and thus is actually deleterious to the primary object of our being there. I cannot see that the coming together of people, possessed of religious feelings, into organizations is essential, or even useful, any more than the assembling of twenty typewriting machines in one room facilitates the working of each individual machine.

“While it is true that men will naturally associate themselves for the discussion of great topics that intimately concern them, it seems to me that religious communion, involving the sense of the relation of the individual to the universe at large, scarcely gains from publicity. And did not Christ himself enjoin his followers to ‘enter into the closet’ for solitary communion with the great things of the universe?

“And then, too, the cloud that may have its silver lining—although it seems a pity that in order to have a silver lining we have to have the cloud—is that when an organization is once formed it tends to solidify in a very unfortunate way; it tends to inhibit real growth in so far as it leads to the establishment of fixed boundaries of dogma that are considered final. No one better than Clifford has insisted upon the absence of finality in one’s system of thought, if growth in mental and intellectual respects is to continue, for the plastic condition only allows growth. And the organization of religion, like any other conventional organization, tends to the establishment of the static condition. I think that a good biological analogy is that of the crustacean—”

“—I beg pardon?” interrupted John.

“He means a crab,” said Calkins, “—a lobster.”

“The crustacean,” continued Crampton “which forms a rigid shell about itself only to find itself cramped and incapable of further development until it casts off the whole incumbrance—truly a painful process, the more so in proportion to the rigidity and insufficiency of the encasement. Is it not better to keep our mental integument, so to speak, soft like that of the humbler worm, so that we may grow consistently and uniformly? For any organization that we may deem final at any time will certainly be found inadequate if our knowledge increases as it should. So I think that the organization of religious views or emotions, besides leading to fictitious results, as Dewey has so well said, really inhibits the free and full development of religious thought, which is, after all, a purely individual thing, an individual function of the human organism.”

“I wonder,” said Mitchell, “whether it would be possible to defend the statement that the more individual a thing is the more it profits from association with other individuals. If so, it would seem to have bearing on what you have just said. It seems to me you rightly insist that religious thought and aspiration are individual, but I suspect digestion is only individual in the sense that each must do it for himself. It does not appear to me individual in any true sense, but, on the contrary, mechanical and formal,— practically the same chemical and physical process in each of us, as incapable of anything really individual as are the typewriting machines of your other illustration.

John Fulton Berrien Mitchell.

“Forgive me for taking these illustrations in another sense from that in which you used them. I quite agree with the point you made, that each man’s religion must be developed and practiced within himself; that he must enter into his closet for prayer and meditation, and express the light he gains in his daily life. But granted this, is there not still use for religious associations or organizations? Our lunch-room conversations may draw the blood from our digestive processes, but they greatly help our thought, and, I believe, considerably improve our literary and scientific productivity, despite the fact that the actual work thereof must be done at other times. I suspect too that the more strongly marked our individuality, the more we can profit by such interchange, so that the more we work alone the more we can profit by association. Just as genius can contribute the most in a conversation, it will also receive the most. Are not both, therefore, needed? Both solitude and companionship? It seemed to me, as I listened to Charley’s account of the Church fellowship, that it was much like that existing among us at the University,—each working on his own line, yet each inspiring others.”

“What I miss in these discussions is the historical view!” said Grant. “My mind cannot get away from the historical facts, or from things as they are. It would need a psychologist, an historian, and a first-class writer of fiction to express what is seething and boiling in me. You professors and scientists take an academic attitude which I cannot follow. You question and analyze the heart out of things, and theorize about facts that are right before your eyes. You walk through them as though they were not there. We must look at facts as they are—as they are—for I must say again that I believe our future idealism is to be found in the heart of the facts of life. Here is organization. Religion always has had organization and it always will have. Here is the Church; it always will be here. The fact that it is is the proof that it is necessary. The fact that I need it and that John Smith needs it and that Sam Jones needs it, and finds comfort or strength in its ministrations, is more convincing than any argument, for it is a fact, and my mind cannot get over facts. Without this fact do you think any organization could have endured for nineteen hundred years? It is not a question whether the Church is necessary. The existence of the Church answers that before it is asked. The question is, how can the human need to which the Church owes its existence be best met and fulfilled?

“Why, the very first impulse of anyone to whom something large and inspiring has come is to go and find someone else to whom he can tell it, with whom he can share it. Moreover, it is never wholly his until he has shared it. Until imparted to another, spiritual experience remains, for a side of our mind, intangible and vague. It is only made perfectly our own as we give it to others and use it in the service of others. Prof. Miller put it very beautifully. Christianity is social, and the Church exists for service,—for the service of man in the spirit of Christ.

“Walk out of the Church? As our young friend did and would have us do? For what end? What was the result? There ought to have been something very great and beneficial to have justified such a startling and unusual procedure. Was he benefited? Or perhaps it was the Church that was benefited? I wish he had told us. The truth is that those who walk out of the Church simply cut themselves away from a wide relationship and a magnificent opportunity of service. Cut off from organization, they are effective neither to help it nor to help the world. That is, not nearly so effective as when they had command of all the machinery.”

“And yet, Percy, the churches too often make it impossible for an independent thinker to remain in their organization,” said Crampton. “Crapsey will serve as an example. Do you not think it very unfortunate to turn such men as he is out of the Church? And if the churches do this, if they permit their obsolete system of dogma, which belongs to an earlier stage of thought, to expel their ministers for simple straight thinking, can they expect to appeal to straight-thinking laymen? Is it not a pity, but is it not also true, that organized religion is exclusive of the free movement of thought; and if we ‘scientists and professors’ neglect the Church, does not the Church neglect us?”

“I was opposed to the trial of Dr. Crapsey,” said Grant. “I do not think the action taken in his case typical of the spirit of the Church as a whole. It was the action of but one court in a single diocese.” Grant held a secret meeting with prominent Episcopalian clergy and layman to see what was to be done for the expelled reverend.

“Yes,” said Miller, “and even that has worked for good. The significance of the Crapsey trial is that it is the last the Episcopal Church will have. It has already refused to try a clergyman who wrote his bishop he agreed entirely with Dr. Crapsey. Thus, though Dr. Crapsey has been unfrocked, his trial has strengthened the liberal movement.”

“I believe Miller is right,” said Johnston. “And not only does it seem to me that the Episcopal Church is broadening, but that the same liberalizing movement is evident in all Christendom, irrespective of denomination. Nowhere, indeed, is it more marked than in Catholicism, particularly among the French Catholics. I have been reading recently some of Abbe Loisy’s writings. Do you know them, Percy?”

“But has not Loisy recently been placed upon the Index?” asked Dewey.

“Yes,” said Mitchell, “but that is the reaction of the external organization—not the true spirit of the Church. I think we must always expect the Vatican to be reactionary. The interesting thing is to see how Catholicism is being broadened despite the Vatican.”

“The crab casting its shell,” said Griscom.

“Exactly,” said Percy in agreement, “and having cast this, it will grow another which must in its turn be cast, and so on indefinitely. But surely the shell must fulfill some function. The trouble is only when an old one is retained too long.”

“Yes,” said Crampton, “but there is a better way than growing shells. The crustacea are not particularly advanced organisms. The churches will be compelled, as they have been at other times in the past, to admit the inadequacy of their present rigid encasement. But it is rather a pity, I think, that when they undergo an ecdysis they immediately replace the old shell with a new one equally rigid, that must itself be discarded at some future time. At least one great lesson of science, the mutability of human thought, is too seldom learned.”

“You have brought the central problem again before us,” said Mitchell. “How can we broaden organized religion, how can we free it from its narrowness and its exclusiveness? How increase its effectiveness? Or, as those of us who are without the Church can do little or nothing, how should those within direct their labors?”

“It is a question of replacing religions by Religion,” said Dewey, “of freeing what is universal from the obscuring limitations placed around it.”

“Precisely,” said Mitchell. “How can we come closer to the unity of life? How can our various religious organizations lay aside their shells and their differences, broaden and purify themselves, that they may fittingly express the great universal current of religious life?”

“Why seek to unify?” asked Montague, still recovering from injuries sustained in the fire which destroyed the Helicon Home Colony. “Why want to break down differences? Why not let Methodists be Methodists, and Catholics, Catholics, and Brahmins, Brahmins? Is not this wide variety of form and symbol valuable in itself? Has not each creed and ceremony a beauty of its own? Should we not rather keep all types, and welcome more, as evidences of the infinite richness of religious aspiration? Why seek to merge in one gray common tone all this rich variety of color, all this wealth of association and tradition, all this living heart-history of the race? Is it not all infinitely beautiful, infinitely pathetic, and infinitely dear?”

“Surely yes,” Mitchell said. “The unity we seek must be the One behind the many; not one instead of many. It must contain within itself all the richness, all the infinite variety of expression, all the impossibility of confinement to a single form. Yet I would have each organization realize this: that, thereby, each may be enriched by the richness of what it seeks to reflect.”

“Is it not a question of emphasis?” Johnston asked. “It seems to me we can get at it in this way. If we study the teachings of the great religious leaders we find two things: First, a distinctly local element, which is, for example, Chinese in Lao-Tze, Indian in Buddha, Persian in Zoroaster, and so on; and, second, we find a universal element which is the same in all teachings. Is not the latter ‘Religion,’ with a capital R, and is it not to be learned by a sympathetic, comparative study of religions, seeking the part common to all? It seems to me this comparative study gives us exactly what Dewey is asking for—the pure spirit of Religion—apart from all local and personal elements. What is true of the great religions is equally true of the sects of each, and I think we could approach unity without impoverishment, if each denomination would dwell upon that which is universal in its belief and service, and recognize the rest as personal, not to be forced or required. If we dwell upon that which is universal, we approach unity. If we dwell upon what is personal, we create only difference and discord.”

“If the churches would do that,” said Crampton, “they would find themselves as united to Science as they would be to each other. But they must do it. We cannot.”

Exordium: Conscientious Clergyman.

Chapter I. The Nature of the Inquiry.

Chapter II. Christianity and Nature.

Chapter III. Evolution And Ethics.

Chapter IV. Power, Worth, and Reality.

Chapter V. Pragmatism and Religion.

Chapter VI. Mysticism and Faith.

Chapter VII. The Historian’s View.

Chapter VIII.Organization and Religion.

Chapter IX. The Theosophical Movement.

Chapter X. Signs of the Times.

Chapter XI. Has the Church Failed?

Chapter XII. Silence.

CITATIONS:

Higgins, Shawn F. “The Benedick: An Analysis of Talks on Religion.” Dewey Studies. Vol. VI, No. 2. (2022): 16-75.