THE ENGLISH IN INDIA PART I.

⸻

Charles Johnston’s history of British rule in India from his essays “The English In India” (May 1909 issue of The North American Review,) and “A Perspective On India,” (December 1926 issue of The Atlantic Monthly.) I have included minor spelling edits for sake of clarity, and expanded some references which are found in the brackets. —S.

⸻

In much that has been written recently in a sense hostile to the work of England in India, there are certain tacit assumptions. The first is, that the English went to India as ruthless conquerors, destroying a national culture which had many of the elements of the golden age. But the truth is, that the English went to India not at all as soldiers or conquerors, but simply as a “company of merchants of London trading to the East Indies.” England was then in the full flow of a splendidly creative epoch. Englishmen had been heartened by the defeat of the great Spanish Armada twelve years before. Sir Francis Drake’s voyages up the coast of California and across the Pacific and Indian oceans had kindled the imagination of his country; Sir Walter Raleigh had explored the marvelous forests of Guiana; English merchants were beginning to find their way overland to India. The outflow of national genius was equally shown in the tragedies of Marlowe, the poems of Edmund Spenser, the sonnets and early plays of Shakespeare.

The East India Company, the London Company trading to Virginia, the Plymouth Company, were all a part of the same out flowing tide. The forces that led Captain John Smith to found Jamestown, on the fringe of the Virginia forest, in 1607, at the same time carried Captain Hawkins to Surat in Western India, with a letter from James I to the Emperor of Delhi. So close is the relation between the two movements that we find the same adventurous spirits appearing now in the factories of the East India Company, now in the settlements on the American coast. And we have just been reminded that Elihu Yale served as Governor of the Council at Fort George in Madras before he came to Connecticut as Governor and founder of [Yale University.]

For the century and a half from 1600 to 1750, the English took no part in Indian politics, and occupied no territory but the ground on which their warehouses were built. This century and a half saw a splendid contest between the most virile nations of the West throughout the seven seas. Italy, Portugal, Spain, France, England, and at a later date Germany and Scandinavia, all entered the lists. But so far as India was concerned, their rivalry was commercial only. At many of the Indian trading towns Dutch, Portuguese, French and English merchants had their warehouses side by side.

Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor.

About 1750 the change came, and it came once more as a part of a world-movement. The impetus was given, oddly enough, by the death of the Emperor Charles VI, and the contest for the succession to the imperial crown [known as the War of the Austrian Succession.] George I and George II, as Electors of Hanover, were drawn into the contest. Louis XV of France took the opposite side. War broke out between France and England, became quiescent, and again broke out in 1754.

This war [the Seven Years’ War] had results which changed the face of the world. France and England fought their battles in two hemispheres. The struggle raged from the Ohio River to the Ganges. Colonel [George] Washington and Colonel [Robert] Clive were fellow officers in the same contest; the capture of Madras by Labourdonnais and the disaster of Braddock’s Field were parts of the same cycle of events. In both hemispheres the English won. [The French and Indian War,] the struggle along the Mississippi and the St. Lawrence, gave the English the supremacy in North America. The contest on the Bay of Bengal and the Ganges laid the foundation of the British Empire in India.

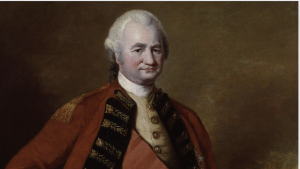

Robert Clive.

Was the founding of the British Empire in India the death knell of a great national culture, a culture of the golden age? One must be singularly ignorant of Indian history to imagine anything of the kind. It is hard to point to any period during the last three thousand years when India was in any sense a nation. It is easy to point to periods of centuries at a time when India was an arena of warring nations, representing hostile races, opposed ideals, mutually unintelligible tongues. India was no more a unit than Europe; and if long centuries ago an Ashoka or a Samudragupta had united many kingdoms under a single despotic rule, the death of the despot had always been the signal for decline and dissolution. But even this degree of national life had perished utterly, long before 1750. More than a thousand years of conquests and foreign invasions by the Arabs, Turks, Tartars, Persians, and Mongols had carried fire and sword from the Himalayas to the extreme south of the peninsula. And while it is true that the Rajputs, with their splendid feudal aristocracies, had fought heroically against the Muslim hosts from northwest, yet it is unfortunately true that we find among little that can be called national or patriotic feeling for as a whole. The Mongol or Mughal emperors again and again enlisted the Rajput princes under their banners, and the greater part of India was won for the Mughals chiefly through the military prowess of their Rajput allies. More than this, the Rajputs were at the same time waging wars of their own, not only against other Hindu princes, but even among their own clans. And all these Indian wars were accompanied by plundering, slaughter and devastation to a degree that we can hardly realize today. Opening a History of India at random, I came on the follow passage from the central period of Muslim invasion:

The king’s exactions, which were always excessive, were now rendered intolerable by the urgency of his necessities: the husbandmen abandoned their fields, fled to the woods, and in many places maintained themselves by rapine; many towns were likewise deserted, and Mohamed, driven to fury by the disorders which he had himself occasioned, revenged himself by a measure which surpassed all his other enormities. He ordered out his army as if for a grand hunt, surrounded extensive tract of country, as is usual on the great scale of the Indian chase, and then gave orders that the circle should close towards the centre, and that all within it (mostly inoffensive peasants) should slaughtered like wild beasts. This sort of hunt was more than repeated; and on a subsequent occasion there was a general massacre of the inhabitants of the great city of Canouj. These horrors due time to famine, and the miseries of the country exceeded all power of description.

Three-quarters of a century later, one reads:

Plunder and violence brought on resistance: this led to a general massacre; some streets were rendered impassable by heaps of dead the gates being forced, the whole Mogul army gained admittance a scene of horror ensued easier to be imagined than described.

This is a scene from Timur’s frightfully destructive invasion. The slaughter of the inhabitants of Delhi lasted for days. A century and a quarter later, we learn that “Babur’s conduct to the places where he met with resistance was as inhuman as that of Tamerlane (Timur.)” The history of the empire founded by Babur has one bright epoch in the splendid and tolerant reign of Akbar. On the other hand, throughout the whole of this Mughal dynasty, we find horrible conspiracies of sons against fathers, and frightful contests, whether of force or fraud, between brother and brother.

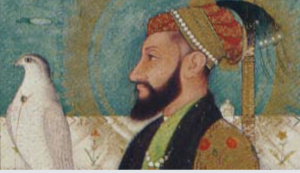

Akbar.

Let us pass over two red centuries, and come to the period on the eve of 1750 and the war between France and England. Here is a scene from 1739:

The slaughter raged from sunrise till the day was far advanced, and was attended with all the horrors that could be inspired by rapine, lust and thirst for vengeance. The city [Delhi] was set on fire in several places, and was soon involved in one scene of destruction, blood and terror […] Every species of cruelty was employed to extort these contributions. Great numbers of the inhabitants died of the usage they received, and many destroyed themselves to avoid disgrace and torture. Sleep and rest forsook the city. In every chamber and house was heard the cry of affliction. It was before a general massacre, but now the murder of individuals.

To say nothing of wars among the Indians themselves, there were no less than four Afghan invasions of India in the twenty years after this last sack of Delhi. The Mughal Empire was falling to pieces in a ruck of blood, treachery and massacre.

Shivaji.

But, it may be said, there were elements of power springing up from the older Hindu races. They might have brought regeneration. It is quite true that new forces were making themselves manifest. Let us see what promise they held for the better government of India. Of these new powers, two stand forth conspicuous: the Marathas in the south, and the Sikhs in the north.

Here is a picture of [Sivaji Bhonsle I,] the heroic founder of the [Maratha Empire]:

The [Maratha] consented to receive his assurances of forgiveness at a personal interview, if the Khan would concede so much to his fears as to come unattended for the purpose of meeting him. Afzal Khan on this quitted his army, and went forward with an escort, which he was afterwards persuaded to leave behind, and advance with a single attendant. He was dressed in a thin muslin robe, and carried a straight sword, more for state than any expectation of being required to use it. During this time Sivaji was seen slowly descending from the fort: he advanced with a timid and hesitating air, accompanied by one attendant, and to all appearance entirely unarmed; but under his cotton tunic he wore a shirt of chain-armor, and, besides a concealed dagger, he was armed with sharp hooks of steel, which are fastened on the finger lie concealed in the closed hand, and are known by the descriptive of “tiger’s claws.” The Khan looked with contempt on the diminutive figure, which came crouching on to perform the usual ceremonies of meeting; but at the moment of the embrace, Sivaji struck his claws into his unsuspecting adversary, and before he could recover from his astonishment despatched him with his dagger.

Sivaji had begun his career by robbing his father. He continued it in plundering, devastation and treachery, and founded a power which lasted for nearly two centuries, and at one time dominated all India, from the Punjab in the extreme north, to the of the peninsula. During the whole of this period, the history of the Maratha power is one long record of craft and rapine; and there is absolutely nothing to show that any of the warriors and statesmen who directed the policy of the Marathas viewed the purposes of government as anything else than the organization of robbery.

Sivaji injuring Afzal Khan.

Let us turn for a moment to the Sikhs, the other native Indian power which was rising from the ruins of the Mughal Empire. There is much that is attractive about the Sikhs, their sincerity, their courage, their devotion to their ideals. whether there was anything in their spirit to insure wise government, the following sentences will sufficiently show:

The severities of the Moguls only exalted the fanaticism of the Sikhs, and inspired a gloomy spirit of vengeance, which soon broke out fury. Under a new chief named Banda, they broke from their retreat and overran the east of the Punjab, committing unheard-of cruelties wherever they directed their steps. The mosques, of course, were destroyed, and the Mullahs butchered; but the rage of the Sikhs was not restrained by any considerations of religion, or by any mercy for age or sex; whole towns were massacred with wanton barbarity, and the bodies of the dead were dug up and thrown out to the birds beasts of prey.

These scenes took place some twenty years before the birth Washington.

We have thus taken stock of all the native elements in India, about the year 1750, just before the English conquerors “ruthlessly broke into” that Utopia of the golden age. Let us see, as briefly as possible, how the “conquest” came about. The first shock, as already pointed out, came from the war with France, the same war which made the English masters of North America. But it was some time before there was any acquisition of territory. And it is noteworthy that, so far were the English from any design of conquest, that they seem again and again to have stumbled into a forward policy unwillingly, and on the initiative of their opponents.

Battle of Madras.

Thus it was in their struggle against the French. France, or rather her proconsuls in India, had begun to “play politics” about 1740 [marking the beginning of the Carnatic Wars.] A French fleet attacked and captured Madras [during the Battle of Madras in 1746,] forcing Clive to take to flight.

Joseph François Dupleix.

[Joseph François Dupleix] The French governor of Pondicherry—[which remained a French settlement until 1962]—entered into intrigues with [Anwaruddin Khan, the Nawab of the Carnatic] who [was] rising amid the ruins of the old Mongol Empire. By inducing some of these to take action against the English, he forced the English into Indian politics in self-defence; and, as a result, England presently came into possession of a coast strip in Northern Madras, taking it, not from any native power, but from the French, who acknowledged their world-wide defeat in 1763 [following the Seven Years’ War.] It was in like manner from the Portuguese, and not from any native power, that the English got Bombay [during the Battle of Swally in 1612.]

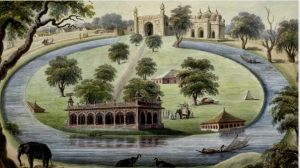

Murshidabad.

In Bengal the English had built up a fortified post at Calcutta. They were under the authority of the Nawabs, the Muslim governors of the decrepit Delhi Empire. The Nawabs of Bengal had their capital at Murshidabad. In 1756 the Nawab, Siraj-ud-Daulah, was a mere youth, wild and licentious like so many of the young Muslim officers. He had a quarrel with a member of his household, who fled to Calcutta and took refuge with the English. When the English refused to deliver him up, Siraj-ud-Daulah marched on Calcutta, captured it, destroyed the factories and warehouses and drove 146 English men and women into a noisome dungeon. By next morning 123 were dead.

Black Hole of Calcutta.

This atrocity of the “Black Hole of Calcutta” brought on war, thus leading to the conquest of Bengal. The decisive battle was fought in June of the following year, 1757, at Plassey, not far south of Murshidabad. The young Nawab of Bengal had 50,000 foot, 18,000 horse, and 50 guns drawn by elephants and served by French gunners. Clive, on the English side, had about 1,100 English soldiers, 2,100 sepoys (native troops) and 10 guns. In the battle his victory was swift and complete. If this was a war of conquest, then we may say that never had a war a better excuse; never was a decisive battle won against such odds.

Siraj-ud-Daulah leading his troops to battle.

Though they had defeated the Nawab, the English did not take possession of his territory. They limited themselves to th exaction of an indemnity; and, with their approval, a new Nawab Mir Jafar Ali, came into power at Murshidabad.

Robert Clive meeting with Mir Jafar after the Battle of Plassey.

The Delhi Emperor was so much struck with the prowess of Clive, who was then only thirty-two, that he granted him the revenues of a district round Calcutta, and a title as an officer the Mogul service. Thus Clive became a landlord under the Delhi Empire, and the East India Company became his tenants. The next step was taken in 1765. The figurehead Emperor at Delhi, [Shah Alam II,] granted a charter, assigning “the Dewani of Bengal, Behar and Orissa to the East India Company.” This charter did no transfer any territory or sovereign rights. Its real effect was t transfer to the East India Company, and to Clive as its representative, the duty of collecting the taxes of these three provinces, which had at the time a population of some 30,000,000. By inevitable degrees, as the Delhi Empire fell to pieces, its power gradually passed into the hands of the Company, who, however continued to recognize the Emperor until 1857. It was as representing the Mogul Emperor that the East India Company excised authority through the Lower and Upper Provinces of Bengal.

The Battle of Assaye, Second Anglo-Maratha War.

Meanwhile, the Mahrattas continued their course of depredation and devastation. They harried southern India. They a tacked the great Rajput clans of the western plains, and were slowly crushing them, and with them all that was noblest and best in India. As the result of three wars [the First, Second, and Third Anglo-Maratha War,] the Mahrattas were finally defeated in 1818.

Ranjit Singh.

Finally, we come to the Sikhs. Ranjit Singh, their greatest leader, was born in 1780, twenty-three years after Plassey. In 1800, he began to build up [the Sikh Empire] under the wing of the Afghans. He died in 1839 without ever having come into collision with the English power. He left no strong successor; and, six years later, the Sikh army, numbering 60,000 men, took the offensive and invaded British territory [resulting in the First Anglo-Sikh War.]

The Battle of Sobraon (1846) during the First Sikh War.

They were completely defeated, but the victors refused to annex their territory, the Punjab. They preferred to set up a Sikh protectorate, recognizing Dhulip Sing as Kaja. Three years later this policy of clemency proved itself a failure. The Sikhs again took the offensive [in the Second Anglo-Sikh War.] As a result, the Sikhs were defeated, and the Punjab annexed in 1849. This practically completes the story of the conquest of India by the “company of merchants of London trading to the East Indies.”

It is a great story, and has the added element of greatness that at no time were the English the aggressors. They fought on the defensive, first against the French, then against the Muslims of Bengal, then against the Mahrattas, then against the Sikhs. If they ultimately came into possession of an empire in India, it was not of forethought, but by natural selection, which first eliminated their European rivals: Portuguese, Dutch, Germans, Scandinavians, French; and then showed that, of all the forces left in India, the English were best fitted to build up a just and conservative rule. Thus the assumption that the British, as ruthless conquerors, destroyed a native paradise is a complete illusion.

We come to the next assumption, that the English have warred against the native spirit and native institutions. Nothing could well be further from the truth. In reality, the genius of England has been, throughout, the genius of conservation: conservation often carried to chivalrous extremes.

Whatever in India was capable of being preserved the English preserved. As we saw, the great Rajput clans, the best and noblest blood in India, were being slowly crushed out of existence by the Mahratta plunderers just a hundred years ago. The English stepped in to shield them, with the result that there are [in 1909] in India eighteen reigning Rajput princes, the total area of whose dominions is larger than France or Germany. To these may be added seven Kshattriya principalities, making a total area of nearly three hundred thousand square miles, an are equal to Great Britain and France combined, under the rule of the old military races of national India. It is not too much say that, in all probability, not one of these five-and-twenty principalities would be in existence today but for England’s genius of conservation. Through the operation of that genius, it comes that the splendid houses of Udaipur, “the dwell of the sunrise,” Jaipur, “the dwelling of victory,” Jodhpur “the dwelling of warriors,” and their kin, whose ancestry goes back to the dawn of time, are still among the reigning kings the earth.

But England’s principle of conservation was not limited to the old national kingdoms. It extended equally to whatever was capable of being preserved among the Muslim powers. Foremost among these comes southern Hyderabad, equal in area to Great Britain, represents the territory which one of the great Muslim deputies, Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, carved for himself from the crumbling ruins of the Mughal Empire.

Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah.

And in spite of many shocks and difficulties, the descendant of [Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah] rules and reigns in Hyderabad [in 1909.] More than once a some what vigorous helping hand has been necessary, as in the case of nearly all the native states; but it is, nevertheless, true that Hyderabad still preserves the forms and something of the spirit of the Mogul Empire, with the elements of savagery and rapine left out.

There are six or seven more Mussulman principalities, each conserving its own spirit, life and customs. One is ruled by a Sunni, one by a Shia, two by Pashtuns, one by an Afghan, and so forth. All represent old adventurous elements of the period of invasion. In the same way there are three Mahratta states, representing the spoils of the great plundering Maratha Empire. Gaekwad of Baroda, Scindia of Gwalior, Holkar of Indore, are the descendants of three adventurous warriors, soldiers of fortune of the palmy Mahratta days so graphically pictured by the Marquis of Hastings. There would have been a fourth Mahratta state, in Nagpur, had not the Bhonsla Raja, descendant of another soldier of fortune, died without issue.

In like manner, the English have conserved the Tibetan Buddhist state of Sikkim, and two Jat states on the fringe of the Rajputs. There are four Sikh states, the debris of the Punjab; and it cannot be doubted that the whole Punjab would remain a self-governing Sikh kingdom but for the two wars of aggression already chronicled. But it is equally certain that the populations formerly governed by the Sikhs have greatly benefited by the change. Their loyalty to the English, and their enthusiastic support in the great [Indian Rebellion of 1857,] sufficiently show their gratitude and sense of obligation.

So we have this long series of native states, with a total area of nearly seven hundred thousand square miles, and a population of over sixty millions: Rajput feudal aristocracies, old Brahmanical kingdoms, bits of the Mongol Empire, debris of the Afghan invasions, Sikh principalities: a vast museum of past centuries, to testify to the English spirit of conservation, which has shown itself as beneficent in India as in Egypt.

In another way this same spirit has been not less effective. In India there are half a dozen great religions, and scores of smaller faiths. None of these except Buddhism had a genuine spirit of tolerance. Brahmanism was the most exclusive and domineering of them all. We saw what horrible cruelties could be inflicted by Muslims on Hindus, by Sikhs on Muslims, and, to the shame of Western nations, it must be said, the cruelties of the Portuguese Inquisition in southern India were at least equal to the worst of them. [In 1908 Charley would state: “It recently befell me to read the old records, from the late fifteenth century downward, of the first contact of our white races with the colored races of Asia and the races of the New World. And as I read, I felt profoundly ashamed for the men of my own color; whether in the East, or in the West, the tale was marred by spoliation, craft, robbery, violence, dishonor. It is a dark and evil record; and one cannot read it without shame.”]

What has been the attitude of England towards all these warring cults? It has been toleration, the broadest and truest toleration the world has ever seen. Not only are all these heated sectarians taught to dwell together in mutual amity and respect but further there is a defined and fully conscious conservation of whatever is best in the genius of each faith. Each one of the old religions represents not only an attempt to explain the riddle of the world, but also a system of domestic and social life, entering into minute details of sentiment, of habit, of social an personal feeling. The English in India, recognizing this, have followed the lines of natural and age-long growth, and have give to the devotees of each of these different faiths a government harmony with their particular genius. The Manusmṛiti with their developments are administered as the civil law of the Hindus. All personal, domestic and testamentary disputes of the Muslims are settled in accordance with the Qurʾān and its law-books. The same is true for the Jains, the Buddhist, the Parsis. And with this has gone a conservation and cultivation of the ancient sacred idioms of all these old religions. Sanskrit, Zend, Arabic, Persian, all owe much to the fostering care of the India Office. And with the modern tongues the same course has been followed Very much has been done to turn into modern literary languages the popular idioms of the Bengalis, the Sikhs, the Mahrattas the Tamils, the Telugus and a score of other less familiar tongues Thus every one of a score of nations, races and faiths in Ind has a government in its own tongue, in harmony with the spirit of its own history and religion.

Perhaps the best single work in the modern tongues has been the translation into all of them of the Indian Penal Code, an its distribution broadcast in cheap editions. No one not familiar with the hazards of humble lives under Oriental despotisms can realize what a boon is conferred on India by a simple, uniform and impartial system of law, the statement of whose obligation and sanctions is within the reach of every one. For, while preserving to each cult and tribe its own civil and religious law, England has given her Indian possessions a single criminal law, simple, impartial, intelligible. It is a symbol of that complete uniformity of civil rights which England had conferred on each one of the countless millions of India, man, woman or child prince, Brahman or outcast. So much for the spirit of conservation.

A Maratha Durbar showing the Raja and the nobles (Sardars, Jagirdars, Istamuradars and Mankaris) of the state.

Yet again, it is assumed that India is heavily taxed by the English, more heavily taxed than at any time in her past history. This is the assumption. But what is the reality? Under the ancient native despots, like Ashoka and Samudragupta, the peasant was compelled to pay one-fourth of the gross produce of his land to the king’s revenue. One-fourth, that is, must go into the treasury. How much stuck to the fingers of the tax-gatherers is another question. The Mughals raised this to a third, with the same condition. Let me record the candid expression of one of their officials fifty years before Plassey:

Contributions were now levied in lieu of regular revenue, and the parties sent to collect supplies committed great excesses. The collectors of the jizya [poll-tax on non-Muslims] extorted millions from the farmers, and sent only a small part to the treasury. Whenever the Emperor appointed a [Zamindar] / [tax farmer] the Mahrattas appointed another to the same district, so that every place had two masters. The farmers left off cultivating more ground than would barely subsist them, and in their turn became plunderers for want of employment.

A very careful calculation has shown that, in a certain area, the taxes levied by the Mughal Government about the year 1700 were three times the amount collected by the English two centuries later. India has, in fact, the lowest taxes of any decently governed country in the world. Again, England is reproached with keeping a huge army in India. The English army in India numbers, with officers, less than 75,000—to safeguard a population of three hundred millions. Surely this is eloquent enough. Let us compare this with “the good old times.” Chandragupta [Maurya,] we are told, had an army of close on 700,000. The Raja of Vijayanagara, about 1500, had an army of 740,000. Aurangzeb, about 1700, assembled a host estimated at well over a million.

Aurangzeb.

By the middle of the nineteenth century the conquest was complete so far as India was concerned. Later accessions, like Burma and Baluchistan, are beyond her frontiers. Then in 1857 came the [Indian Rebellion.] But it was more than a revolt of the native regiments, and had many contributing causes. One was the rapidly growing tendency of the British power to absorb the Native States, whenever a disputed succession offered a pretext; another was the prophecy that the rule of the East India Company would end a hundred years after Plassey; a third was more potent though less defined: the genius of India felt itself rebuked by the dominant English, as Antony’s genius was rebuked by Caesar’s. Heavy moral and mental pressure, resented as oppression, caused reaction and revolt.

The British recapture of Delhi during the Indian Rebellion.

The prophecy was kept to the ear but broken to the hope. Following the Mutiny, an even century after Plassey, the East India Company ceased to exist and the period of imperial government began. But this was no abrupt revolution. The right of the British Government to supervise the Company was implicit in the original charter of 1600, and as long ago as 1783 Parliament had established a board of control to direct the directors of the Company. The chairman of the board, who was a member of the British cabinet , gradually became the effective ruler, so that after the Mutiny only a change of name was needed to transform him into the Secretary of State for India. The British viceroys had long been appointed, not by the Company, but by the prime minister acting for the Crown. So that the change, when the imperial government of India took form in 1858, was only the final stage of a gradual transformation spread over three generations.

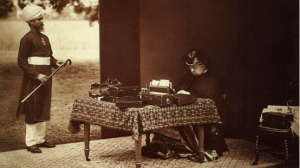

Queen Victoria and an Indian servant.

At the inauguration of the imperial era Queen Victoria issued a proclamation which contained the promise that all government posts in India would be opened to the natives in the measure of their abilities. This sentence came to be regarded as the Magna Carta of India’s liberties.

AGONISED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS.

INTRO: CHARLEY.

I. WITCH TALES.

II. CARELESS WHENCE COMES YOUR GOLD.

III. THE TIMES ARE CHANGED.

IV. DENIZEN OF ETERNITY.

V. DOMOVOY.

[APPENDICES]

THE ENGLISH IN INDIA I.

⸻

SOURCES:

Johnston, Charles. “What The Theosophical Society Is Not.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. VI, No. 1. (July 1908): 22-28.

Johnston, Charles. “The English In India.” The North American Review. Vol. CLXXXIX, No. 642 (May, 1909): 695- 707.

Johnston, Charles. “A Perspective On India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXXXVIII, No. 6. (December, 1926): 848-856.