CARELESS WHENCE COMES YOUR GOLD

II.

⸻

THE FABIANS

“I will not go into the question whether it is desirable that women should work in factories or workshops, for it would be useless to do so,” said Clementina Black. “We may differ upon that point—but short of a social revolution, it is impossible, at the present time, but that a considerable proportion of women should have to work. The fact is—the lamentable fact—that a large proportion of working-women in England are underpaid. When I say underpaid, I mean this: that they do not receive for their work enough to live healthful lives, to be clothed, lodged, and fed properly, and to be enabled to make provision for their old age.”[1]

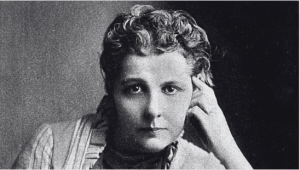

Annie Besant.

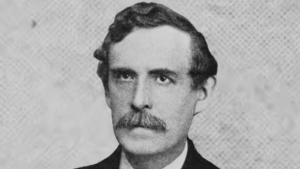

On June 18, 1888, Annie Besant and her fellow Fabians listened attentively to Clementina Black’s lecture, “Female Labour,” in the rooms of 31 Upper Bedford Place. It was the second monthly meeting of the Fabian Society, and Black, the Secretary of the Women’s Protective and Provident League, delivered a strong message. Besides Besant, there was Herbert Burrows, a frequent contributor to The Link, a half-penny weekly that Besant co-edited with her friend (though she wished it were more) William T. Stead. George Bernard Shaw, Sidney Webb, and Graham Wallas were also in attendance; these three men, along with Sidney’s wife, Beatrice Webb (the originator of “Collective Bargaining”) would, in the years to come, establish the London School of Economics. The chair that evening, Henry H. Champion, was a radical Anglo-Indian journalist from Poona, India. They were part of the “working-man’s intellectual elite,” so crucial to the project of the Fabian Society.

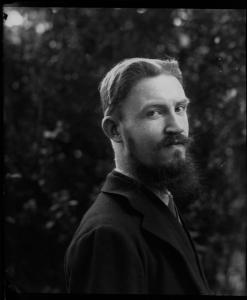

Herbert Burrows.

The Fabians were given their name at meeting in January 1884, at the suggestion of a member named Frank Podmore. It was in honor of the Roman general, Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus, whose strategy against Hannibal’s Carthaginian army relied on a gradual victory through persistent harassment, and gradually reducing the enemy’s strength with drawn out pressure rather than climactic battles.[2] Incidentally, four months after the naming of the Fabian Society, Frank Podmore, and his colleagues the Society for Psychical Research, began their damning inquiry into the Theosophical Society.[3]

Fabian Society logo & coat of arms.

At its core, Fabianism was an intellectual circle that endeavored to permeate all classes, from the top down, “with a common opinion in favour of social control of socially created values.” Recognizing the pitfalls that other Socialist denominations encountered when preaching “class-consciousness,” and the near-impossibility of a sudden “revolution” of the working class against capital, it urged the necessity of “a gradual amelioration of social conditions by a gradual assertion of social control over unearned increment.” Fabians worked through Liberal “capitalists” and Labour representatives alike. Resolved to gradually permeate social consciousness, it relied on the slow growth of opinion over outright revolution. For their logo they chose a tortoise, symbolizing the movement’s plan to slowly transition society into a Socialist project without detection; their coat of arms, “a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” indicated their preferred method to achieve such ends.[4]

Following Black’s talk, conversation turned to the conditions of the working women in East London.

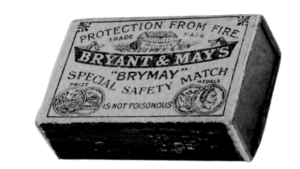

“Bryant and May’s, the match-makers in East London, which numbers twenty clergymen amongst its shareholders, pay a dividend of 20 percent on the capital invested,” said Champion. “The women make the matches at a wage of under a penny an hour. These slaves must be emancipated—as to the method, that is for the educated and propertied classes to say, and to say soon, whether they are to be bought out with money like the slaves of our West Indian colonies, or like the slaves of the Southern States of America, with blood.”[5]

“In the interests of the workers,” said Black, “I support a consumers’ league of persons who pledge to deal only with such firms as are known to treat their workers fairly.”

A resolution was moved by Champion, seconded by Burrows, and carried unanimously:

That this meeting, being aware that the shareholders of Bryant and May are receiving a dividend of over 20 percent., and at the same time are paying their workers only 21⁄4d. per gross for making match-boxes, pledges itself not to use or purchase any matches made by this firm.

When Besant heard the girls reduced to such wages, her common womanhood revolted against the system of oppression, and she felt she could not rest without raising her voice and using her pen against it. She decided that she would personally investigate the working conditions of the matchgirls of Bryant & May’s at their factory in Bromley, East London. Burrows would join her.[6]

MATCHMAKERS.

Bryant and May’s Matches.

“We estimate that 20,000 are dependent, directly and indirectly, upon our matches for their bread. In the works here are some 1,500 men, women, and girls the last in greatest force, of course,” said Wilberforce Bryant, during the course of the tour which he gave to Besant and Burrows. “To work such a business profitably, the manufacture must be conducted on a large scale, and every department reduced to a complete system. The resources of this company are unique.”[7]

There were six match factories in the East End who employed thousands of women and girls. Bryant and May’s was the largest. Next to Bryant and May’s was Bell’s, where five hundred girls and women worked. Bryant looked upon the factory with pride. “One of our greatest difficulties in the early days was the machinery. Match-making was in its babyhood. The machines were clumsy and primitive, turning out the worst article at the slowest pace. We saw this very soon and began to look round to effect improvements. And so, we have gone improving and inventing, buying an idea and perfecting it. We have thousands of pounds in trials alone—thousands of pounds which are by a few tons of old iron, only to be melted up again. But by degrees, the old methods have given way to the new, and now in every branch of our business we have machinery which produces the highly-finished article, at the least cost, with the smallest physical labour, and at the greatest rate.”

The trio continued along their way. “This is where we conduct our mixing operations,” said Bryant as they entered a room where the composition for the different types of matches were made.

There were two groups of men and boys at work. The first group were grinding up chemicals to prepare for mixture; the other group huddled over cauldrons of many-colored liquids, stirring in said chemicals, the primary ingredients being phosphorus chlorate of potash, sulphuric acid, antimony, bisulphite of carbon, gum-Arabic, potassium nitrate, and sugar. When the compositions were ready, they were taken to one of the stone slabs—each of which was presided over by a workman. The composition was carefully poured on the stone by a regulated gauge to a depth of about an eighth of an inch. Each of the frames were then brought to the dipper who dipped both ends of the rigid splints into the mixture making a “double match.” The frames were then carried away to the racks of fire-proof drying rooms.

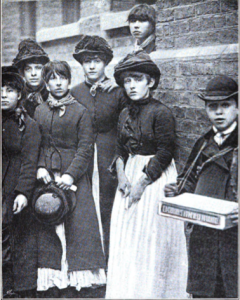

After the matches had time to dry, the contents of the frames were emptied onto tables where the numberless fingers of matchgirls hurriedly cut the “double match” into two with a special lever-knife and filled into matchboxes. The whole scene was filled with defiant life; the girls sang and shouted over the dismal humming whirrs of machinery, a reminder, unnoticed by Bryant, that they were not, themselves, the machinery.

“We estimate that 20,000 are dependent, directly and indirectly, upon our matches for their bread. In the works here are some 1,500 men, women, and girls the last in greatest force, of course,” said Bryant. “To work such a business profitably, the manufacture must be conducted on a large scale, and every department reduced to a complete system. The resources of this company are unique.”

“Burrows, keep talking to Bryant,” whispered Besant. “Mr. Bryant, if you would please excuse me, I am feeling faint. Please, you and Mr. Burrows continue along without me.”

“Faint” could mean any number of things to a lady, and Bryant was not foolish enough to ask. “Would you like an escort from the foreman?”

“No, that is quite alright Mr. Bryant, thank you.”

Once outside the factory, Besant soon found a group of matchgirls. It was said they never responded to “hard words or angry looks,” but “a great deal by kindness.” Before delving into the injustices of the factory, Besant won them over by showing interest in their lives. It was not a ploy. Besant was genuinely concerned. The girls were the same age as her daughter, Mabel. This fact alone could pull a lever in the maternal mechanization of any mother. Besant had two children, Mabel and Arthur, from her husband, Frank Besant. Being an “ill-matched pair,” Besant and Frank separated (though never officially divorced.) Frank won custody of the children, but Besant, having gained the heart of the governess in charge of the children, was able to visit them every week.[8]

“We come out very strong on some Saturday nights,” said one of the girls. “My favorite Paragon Music Hall.”[9]

“‘Specially when someone stands treat, you know,” joked another. “I like Sebright in Hackney, m’self.”

It was clear from the shape of her face, that, owing to her exposure to phosphorus, she fell victim to the disease known as “phossy jaw.” As soon as the symptoms manifested, the sufferer had several teeth removed so that, if possible, the jaw could be saved.

“Are you content with your wages?”

“It ain’t so much the prices as the slackness of work.”

It was summertime, a “slack time” of year in the match-making trade.

“It’s the machines,” said another girl. “The machines have made this penny in the shilling difference to us.”

It was the “onward rush” of the great industrial machine that directed the course of Bryant and May’s business, not the welfare of those immediately beneath its wheels.

“Have you girls any complaints of the treatment you received while in the employment of Mr. Bryant and Mr. May?” asked Besant.

“Yes, of the general fines,” said one girl. “When I was earning only eightpence per day, if I arrived at the gates after twenty minutes to seven in the morning—my time being half-past six—I was fined five pence, and would have to work all that day for the three pence. This might go on for the whole of the week if I were ill. This was in the summertime. In winter I worked from eight in the morning till seven at night, one hour for dinner and no time for tea. If we were caught making tea, the fine would be-half-a-crown.”

“But that is more than half your earnings?”

“Yes,” the girl replied. “We were fined for all sorts of things. I was once fined sixpence for fetching a can of cold water to drink in the hot summertime. We were fined for singing or talking, leaving a few sprints about or dropping a few on the floor. Every month we were compelled to pay sixpence for a broom to keep the machines clean with—our canvas aprons we were compelled to purchase also. The portion of work I do is filling up the frames with sprints to fill two frames, one on each machine, it takes about ten minutes—I received one shilling for one hundred frames. The most I ever earned was nine shillings, but since Easter I have never earned more than five shillings per week.”

Matchgirls.

“Is the work in any way dangerous?”

“I have known several girls to get injured by having their fingers caught in the machines while attending to their work.”

“It is time someone came and helped us,” a pale-faced girl told Besant.

“Who will help?” Besant replied. “Plenty of people wish well to any good cause; but very few care to exert themselves to help it, and still fewer will risk anything in its support. ‘Someone ought to do it, but why should I?‘ is the ever re-echoed phrase of weak-kneed amiability. ‘Someone ought to do it, so why not I?‘ is the cry of some earnest servant of man, eagerly forward springing to face some perilous duty. Between those two sentences lie whole centuries of moral evolution.”

~

Burrows and Besant walked through Bow, discussing everything they had seen, and their next course of action. “There is growing up a feeling of bitterness in our society that looks on law as an enemy and turns men into savages,” said Besant. “Women and children are taking places of men, as machinery is more improved, and greater profits are yielded to the employer. Married women are paid less than men because they will work for less, because they think of the children at home.” They passed The Bow Bells public house where a group of men, women, and children, saturated with gin, huddled outside the entrance. “Another terrible side of it is they have one resource that is not open to men,” said Besant. “Our great employers build homes for fallen women, while they are manufacturing them in their factories. These terrible extremes of society can never be remedied until we have moulded men and women worthy of the name—until we have got rid of the classes who struggle with each other.”[10]

ALCHEMY

The gin-soaked patrons of The Bow Bells, and the phossy-jawed employees of Bryant and May’s, could both trace their conditions to the experiments of ancient tradition that, like Besant, explored the notion of balance.

When the Arab armies conquered Egypt in the 7th century, Muslim scholars encountered an ancient philosophy known as Hermeticism (a Neoplatonic cosmology that fused the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth.) The throughline for this nebulous collection of beliefs, was the figure of Hermes Trismegistus (Thrice Great,) who some regarded as a prophet. These Islamic scholars developed a spiritual practice with this newfound knowledge which they called al-Khemiya (Alchemy,) or the “science of Khem” (Khem being an ancient name for a part of Egypt.)

A summary of the Hermetic design of the universe was a “Great Chain of Being” that looked something like this: All of creation radiated from God (Monad,) and earth was but one part of a sacred Unity. The universe was apportioned into three emanations, or realms. The highest emanation was the supercelestial realm of Nous (the Divine Intellect.) Nous was populated with angelic spirits, whose proximity to God granted them a superior knowledge of reality. The Middle Plane was the realm of the stars, spirits, and “guardians.” The lowest plane was the realm of Nature, which experienced divine influences that trickled down from the two sacred realms above it. Hermeticism sutured the wound of divine divide by affirming that the Creator required its creation to be a Creator. It was humanity’s purpose to achieve the wisdom of the Creator—(theo-sophy.) The Hermetic scheme envisioned spirituality in cycles of gradual human perfection, with the end result being the soul’s reunification with the Divine Consciousness of God.

Alchemy, though popularly understood as being the pursuit of turning base metals into gold, was also an examination of the spiritual nature of material existence. Experiments dealing with the mysteries of birth, death, and resurrection were conducted in both material and spiritual laboratories. Observations of the different stages of chemical distillation and fermentation helped answer some of these mysteries and, once systematized, could be used as a tool to quicken nature’s processes.

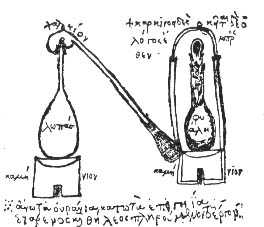

Hermes Trismegistus

One of the greatest of the Alchemists, a Persian named Jabir ibn Hayyan, invented the alembic still in his scientific pursuit. The airtight covering Jabir used was said to have come from Hermes Trismegistus himself—and was therefore regarded as the Hermetic Seal. Using the alembic, an Alchemist would place a material-soaked solution over a heat source. As the material heated, its “spirit” would be released and transferred through connective tubing to another vessel. Multiple distillations would render a more refined “spirit,” an al-iksir (elixir) with healing properties. Over time, the general expression for Alchemically refined ore, al-kuhul (alcohol,) became the general expression for anything purified or distilled.

Alembic Still.

After successfully distilling pure spirit from coarse matter, the Alchemist proceeded to the final stage of the process, the admixture of the refined elements into a spiritual unity. It was represented in the Hermetic tradition by the marriage of the creative life-giving elemental forces by sulfur (masculine,) and mercury (feminine.) This “Alchemical Wedding” was symbolized in the marriage of Hermes and Aphrodite, Herm-aphrodite. If the re-union (masculine/feminine, spirit/matter) was achieved, the result was the “fifth element” or “quint-essence,” also known as the “Philosopher’s Stone.” This was the Alchemical “gold.” This was the “great work” of the Alchemist—the “Magnum Opus.” Jabir recorded his experiments in a coded language that made it nearly impossible for his European counterparts to decipher—a code which the Europeans referred to as “Jabir-ish” (gibberish.)[11]

The knowledge of distillation, nevertheless, eventually made its way to Europe in the late sixteenth century. These Alchemical elixirs soon became famous for their magical property and were known as aqua vitae—the water of life. This terminology was preserved in many European languages, like eau-de-vie in French, or the Irish uisce-beatha (whiskey.)[12] Gin was another such Alchemical aqua vita, first distilled with jenever in the mid-1600s. At the same time, in 1669, a German Alchemist named Hennig Brand believed that human urine might hold the key to achieving the Philosopher’s Stone. In this pursuit, Brand visited the local pubs where he found many patrons of science eager to supply him with generous personal donations. When Brand distilled the urine, a pale, waxy, highly-flammable substance was produced. Brand called this substance phos-phorus, or “bringer of light.” It was keeping with the theme of the “light bringer” of the late 1660s.

Casting out the rebel angels in Milton’s Paradise Lost.

Two years before Brand’s discovery, John Milton reimagined the character of Lucifer (“light-bringer”) in his epic English poem, Paradise Lost. In 1833 phosphorus and chlorate of potash were combined, producing what may be termed the first proper match. Because of their ability to produce light, as well as their distinctive sulphuric smell (associated with the fire and brimstone,) the first matches were, appropriately enough, known as “Lucifers.”[13] As one Alchemical maxim stated: “As above, so below.” But one did not need to be trained in the Alchemical arts to see how that maxim could apply to society in general. The polarities of man/woman, east/west, rich/poor, science/religion, etc. had become unstable elements in the laboratories of modernity. Parliament, Bryant and May’s, and the matchgirls, formed a material “Great Chain of Being.” Whatever fate had in store for the matchgirls, it would certainly electrify the hierarchical tether. Those at the top could very well pantomime as gods, but the inverse of the maxim was equally true: “As below, so above.” As Milton noted, it did not bode well for heaven when light-bringers revolted.

WHITECHAPEL

Petticoat Lane.

A few days after the visit to Bryant and May’s, on June 23, 1888, Besant’s article, “White Slavery in London,” was published in The Link.[14] It exposed the draconian working conditions of Bryant and May’s. On June 27, while London discussed the exposé, Besant and Burrows made their way through Whitechapel en route to a meeting of the London Tailors’ Association, to speak on the “sweating system” at St. Paul’s Hall, on Goulston Street.[15] Whitechapel was a neighborhood just north of the Tower of London on the Thames. Being just a few blocks up the river from the famous London Docks, many men employed along the river, and the “numerous water thieves of the wharves” lived within its borders. A hundred years earlier, in the time of George III, Whitechapel was just outside the eastern walls of London—a suburb of sorts for underpaid laborers who had little money for rent, but who flocked from the countryside to find work in the industrialized metropolis.[16]

“Hunting for bargains.”

Gas glared from primitive tubes on the long vista of Petticoat Lane. Hearts, kidneys, livers, loins, and shoulders hung from the butcher carts. On the other side of the pavement were innumerable lines of barrows and baskets. Planks on trestles were burdened with oysters, cheese, produce, and fake flowers. Others sold soap, candles, crockery, and ironware. Other merchants sold spiritual nourishment in the form of Ḥumashim, bentchers, and religious paraphernalia.[17]

The air was heavy with the smell of fried fish—one of the many dishes which the recent wave of Jewish immigrants brought with them to England. Chunks of halibut and plaice, dipped in batter, and fried in boiling oil, were sold for a penny and two-pence a junk. They were served with fried potatoes in the French style, that is, “in long narrow slices.”[18] The dish had grown in popularity in recent years, especially in the “low neighbourhoods” of Soho and Whitechapel. Another peculiar species of food that could be had for a halfpenny, were the boiled cucumbers soaked in a solution of vinegar and salt water. These were regarded as a delicacy. The immigrants, many of whom arrived from Germany, still referred to them by their German name, “pokels.” There were some in this community of exiles that claimed the practice of eating fish with cucumbers derived from Numbers 11:5: “We remember the fish we ate in Egypt at no cost—also the cucumbers, melons, leeks, onions and garlic.”[19]

A babble of voices filled the air. Every now and then a great wave of laughter broke out, only for it to crash back into the ocean of roar.

“‘Ere yer are. The greatest hinvigerater on the face of this earth! Are yer feelin’ seedy?” shouted a salesman.

Their curiosity piqued, Besant and Burrows stopped to listen.

“Is yer waistcoat loose cos yer didn’t ‘ave no breakfast this mornin’? Are yer feelin’ a bit queer after that spree yer ad last night? If so, just yer try a glass of this world’s greatest benefactor.”

The crowd nodded.

Good salesmen knew how to sell a solution. Great salesmen knew how to sell a problem.

“My hinvigerater will put yer right!” said the salesman, producing a narrow, long-spouted, bottle. He shook a tiny bit of a red potion into another glass that was half-filled with a yellow liquid. “Only a penny a glass!”[20]

The persecution of Jews in Eastern Europe produced a distinct effect on the industries of East London. The influx of immigration assumed greater proportions after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II of Russia, by the terrorist group, Narodnaya Volya (“The People’s Will.”) The Russian government claimed that it was Jewish conspiracy, even though only one of the ten members of Narodnaya Volya, Hesya Helfman, was Jewish.[21] In 1882 targeted attacks against Jews, known as Pogroms spread across the Russian Empire. Acts of mob violence known as “Judenhetze,” or “Jew Hunting,” became widespread.[22] In 1882, a Mansion House Committee was convened in Britain to help raise the necessary capital to assist in the evacuation of endangered Jews from Continental Europe. “England was only a half-way house,” it was said, “the mass of the immigrants passed further.”[23] The Jewish Board of Guardians would help them re-settle in America. The situation changed, however, when New York passed legislation banning immigrants unless they had £20 capital, or proof that they had friends who could guarantee them work. Unlike most other nations, Britain had a very liberal immigration policy, and with nowhere else to go, many Jews settled in Whitechapel. It did not take long before they fell victim to the predatory practice of the “sweaters.” Just as machines changed the process of making matches, so too did it change the process of garment-making, and other like trades. “Sweaters” were a subcontractors, middle-men, who operated production facilities known as sweatshops, where poor immigrant laborers worked long, grueling hours, assembling garments and the like in the fashion of an assembly line. The conditions were barbarous and paid very little. The “sweating system” had disastrous effects of the entire ecosystem of labor and laborers. Writing for Oscar Wilde’s magazine, The Woman’s World, in late-1888, Harriette Brooke Davies observed:

The overflow of foreign cheap labour is a calamity that can hardly be understood or estimated, even after a careful study of statistics published a few days ago. Nothing on paper can adequately describe the sufferings of men and women who have to compete with foreign paupers. Slowly and steadily this avalanche of cheap foreign labour is crushing our English workers out of place. Again, the minute subdivision of labour has a disastrous effect on wages; where no special skill is required, wages must of necessity be comparatively low. Few persons can cut out and make a complete suit of clothing; to do so requires long training and practice; but any average worker can press seams, or make button-holes, or work a sewing-machine. Once it took a tailor to make a suit of clothes; now it takes half a dozen men or women who know absolutely nothing about tailoring as a whole to produce it. Over-population and the crowding into great cities are the cause of much poverty among the working classes. It seems hard to blame anyone for exchanging the dull routine of a country life for the real or imaginary delights of a city; but there must come a time when even London will have to stand still, or more likely retrograde. It cannot go on increasing forever and finding occupation for the thousands of persons that come flocking into it annually.[24]

A Board of Trade report, published at the time, stated that the flow of immigration to East End was “acutely felt by English workpeople,” adding that “Englishmen [were] gradually being forced out of [their trades.]” The sentiment was captured in an 1886 article from The St. James Gazette:

Deeply as we may pity them, charity begins at home; we have no cause to lift this burden too on to our shoulders; and it is something to the tailors and shoemakers of the East End that their wages are being driven below subsistence point by the fierce competition of a starving foreign population ready to work for what, judged by English standards, are literally starvation wages.[25]

It was a period of global economic troubles known as the “Long Depression.” Lack of employment, scarcity of income, high taxes (imperial and local,) riots, and political uncertainties were commonplace. Life in the London was “not hopeful or cheerful,” and every grievance was “raked up, magnified, tossed up and down, and nursed.” A bitter feeling of hatred for the immigrants was stewing in the hearts of the East End’s natal poor.[26] A letter from an 1886 issue of The Pall Mall Gazette stated: “That there has been no rising against this flood of cast out Continental Israelites does credit to the heart of the English population who, fearing to be charged with religious prejudice, keep silent. Yet it is a very serious matter.”[27]

“On the fringe of the crowd.”

Racial tensions were high. The immigrant Jews were faced with a no-win situation. Without a homeland to call their own, they were forever subject to the mercurial moods of hostile nations. It was during this time that wealthier Jewish patrons began to sponsor colonies in Ottoman Palestine. The St. James Gazette noted in May 1888, that while there were only 5,000 Jews in Palestine in 1880, by 1888, the number of Jews who returned to their promised land had risen to 30,000.[28]

Every few steps in Whitechapel revealed a passageway leading out of lane like tunnels in a mine—but no cave could be more gloomy or forbidding.[29] Besant caught the forlorn eyes of one of the 1,200 prostitutes “of very low class” who lived in Whitechapel.[30] Besant, a supporter of the Malthusian theory of population control, believed that the “preventive checks” of social eugenics could remedy society’s ills. In her essay, “The Law of Population,” she stated that with guided measures of birth control: “Prostitution would cease to flaunt in our streets, and the sacred home would be early built and joyously dwelt in.”[31]

“Typical Court in the Jewish Quarter.”

It was difficult to convey to people who only knew a happy and comfortable home, how empty pantries, starving children, and a sick spouse, could make life so intolerably hideous. How could anyone accurately describe the endless nights robbed of sleep, that an entire family experienced when huddled together in a single tiny room. Damp walls and a leaky roof could corrode the soul of even the best-tempered person. It was always the same script with the critics: “Don’t regard East London as a field for experiment.” “Don’t come there to air your doubts. There are enough people infusing doubts for their own ends. You will only muddle those who are groping their way, and beating out life’s problems for themselves.” “Don’t come and tell that Buddhism, Mahomedanism, and all other –isms, are very well in their way. There is no cure for East London but Christianity.”

London Hospital, Whitechapel.

The voyeurism (bordering on fetishization) of suffering had developed into an uncanny séance. Like the famous actresses of the Lyceum theatre who now found it fashionable to visit Joseph Merrick, the “Elephant Man,” hidden away in the nearby London Hospital—it was for social capital; it was the “sham pretense of humanity.”[32]

Joseph Merrick.

Five hundred people, many of them immigrants from the sweatshops, crowded Goulston Hall that evening. Charles Conybeare, M.P., took the chair, and was supported on the platform by Besant, Burrows, Lewis Lyons, Cuninghame Graham, M.P., and others.

St Paul’s German Church/”Goulston Hall.” c. 1887. (Survey of London.)

“The evidence recently given before the Sweating Committee of the House of Lords,” said Conybeare, “is proof that no exaggeration has been used in the early days of the agitation against the system. But all the Royal Commissions in the world cannot cure the evils complained of. The only remedy possible, and it is a socialistic one, I frankly confess, is to give into the hands of the people the control of the means of production which is now in the hands of the classes. Sweating, after all is nothing more than the extraction of the due earnings of the laborer by the landlord and capitalist classes, and the only way to cure it, is by the people themselves organising and combining—by establishing cooperative workshops, and thus getting the production into their own hands. It should be not only a national, but an international combination!”

A resolution was unanimously passed:

That this meeting, having read the evidence given before the Lord’s Committee on Sweating, considers the method of production known as the sweating system inhuman and barbarous; that Mr. Cuninghame Graham, Mr. Conybeare, and Mr. Bradlaugh be asked to introduce a new Factory Bill, to contain clauses which shall provide for the registration of workshops, and that no workshop be open for more than eight hours during every twenty-four hours.

Besant was loudly cheered when she stood to deliver her speech. “Since the passing of Mr. Bradlaugh’s Truck Act, all fines in workshops are illegal robbery, yet the workers do not dare complain. I urge the men to unite—unite till they have the courage to speak out.” Besant’s low voice had a carrying power often found lacking in louder voices.[33] “No power on earth can save them. The slavery in England is worse than in slave countries, for here the men cost nothing to buy—their lives are valueless. If they would unite, they can win—but they themselves must fight out their own salvation.”

When Besant returned to her seat, she saw one of her worker friends in the back of the hall gesticulating that he had a message. Lewis Lyons had just moved a resolution condemning the Merchant Tailor’s Guild for misappropriation of funds, so she was compelled to remain seated.

“I come here tonight to show that I am earnest, and to infuse some of my earnestness into you,” said Cuninghame Graham, in support of Lyon’s resolution. “On behalf of Mr. Bradlaugh, Mr. Conybeare, and myself, we pledge to do our utmost for democracy. I will not rest until the social condition of England is radically changed!”

As the crowd applauded, Besant excused herself from the platform and made her way to her friend in the back of the room.

“Let us speak outside,” he said.

The atmosphere was thick and fetid. Fog hovered in the alleys like lead. The coil of the leviathan of night slowly strangled the luminescence out of the flickering, dying light. The few scattered gas-jets which burned along Goulston Street were hardly visible ten steps away.

“Yes, what is it?” Besant asked.

“Three girls came to me crying today saying they ‘got the sack,'” he said. “The Bryant and May’s factory is in a state of commotion. The girls are being bullied to find out who gave you the information printed last week.”

The worker friend then took Besant to meet with the women themselves, Sarah Chapman, Mary Cummings, and Naulls, who recounted the story themselves.

“Some of the girls were spoken to about the things mentioned in The Link,” said Chapman. “They were shown a paper and asked to sign it.”

“What was the motive of this paper?” asked Besant.

“It was for the purpose of proving that all that you had stated about the fines were lies. The girls said that it was all quite true, and that they would not sign the paper. One of the girls, pitched on as ‘our leader,’ was threatened with dismissal, but she stood firm.”

“I urge you to go back and fight for the wages due to you,” said Besant. “I promise you that you shall not be left unsupported.”

LONDON PATRIOTIC CLUB

On the evening of July 2, Besant, Burrows, Conybeare, and Cuninghame Graham, joined the members of the London Patriotic Club for a “welcome home” dinner given to one of their comrades. Edward Sullivan, the guest of honor, was arrested six months earlier after being beaten by the police in Trafalgar-square during the events of Bloody Sunday. Having been released from Millbank Prison earlier that morning, he enjoyed himself “with all the relish of a man who has been deprived of a good meal for half a year.”

When the tables were cleared, the chairman of the London Patriotic Club, Mr. Fuller, presented Sullivan with a purse which had been subscribed to him by his comrades. “I propose a toast to the ‘Champions of Liberty,'” said Fuller. “To Mr. Sullivan and Mr. Graham!”

After the toast was enthusiastically consumed, the audience rose to sing: “For he’s a jolly good fellow, for he’s a jolly good fellow. For he’s a jolly good fellow, and so say all of us!”

“I want to thank my wife, family, and friends for the kindness they’ve shown me during my imprisonment,” said Sullivan, in a voice broken with emotion.”

“I think the time has come to do something definite in regard to Trafalgar-square,” said Graham. “If the workmen unite on this matter, they could have such a gathering in the Square that neither would tyrannical Tories put them down by force, nor sneaking Liberals stand aside and see them kicked.”

“What the ‘radical cause’ wants,” said Conybeare, “is a program that should, in the first place, be a repeal of what mischief that has been done by the present Government, and in the next a positive program of reform. This reform must be firstly political, including adult suffrage, triennial parliaments, and payment of member. Having secured their position by these means and got into their own hands the machinery of government, we should be better able to carry social reforms.”

“Much good work has been done by The Law and Liberty League,” said Besant, remembering her time with Stead a year earlier. “They have not only helped to support Sullivan’s family, but, owing to their action, not one of the homes of the imprisoned men has been broken up. I need only remind you that the tyranny of the policeman-dictator has supplanted law and justice as evidence for need of such an organization.”[34]

REBEL ANGELS.[35]

“Annie Besant!” “Annie Besant!”

In the late afternoon of July 6, 1888, Besant looked out the window of her Fleet Street office to find hundreds of match-girls marching and chanting.

“Too far without brakes!” “We’ll have our coppers; glory, hallelujah!” “Annie Besant!” “Annie Besant!”

Once again, Chapman, Cummings, and Naulls came to speak with Besant.

The girls explained how the co-worker that was pitched as their leader had been “discharged over some trifle.” In solidarity, 1,400 girls threw down their work and went on strike.

“Did you work the whole of the week previous to the strike?” Besant asked?

“Yes—I was there the whole of the week,” said one of the girls, “but I lost time waiting for work, and took a little over three shillings that week.”

“Were you ever kept waiting for work?”

“Yes, frequently—and we were always afraid to leave the place for fear of not getting any more work that day.”

“Will you tell me how you are living now?”

“Well, mother makes matchboxes when she can get them, but for the last two weeks she has had no work on account of the strike.”

“Your father?”

“He’s earned one shilling this week—besides the little he can borrow from others, almost as poor as ourselves—that’s all we have had to live on, and five of us in the family.”

“But surely your father cannot pay rent and keep you all on such a sum. What do you do?”

“No, the rent is going back,” she said with tears forming in her eyes. “As to living, why, when we can get a bit of bread and butter, we’re very thankful for even that, and when we can’t, we must go without.”

“We came to ask you what to do next,” said Naulls.

“We’d ‘ave come out before,” said Cummings, “only we wasn’t agreed”

“You spoke up for us, Mrs. Besant,” said Chapman. “We weren’t going back on you.”[36]

Bryant and May’s tried to spin the narrative in their favor. “The whole agitation was a cruel business for the workpeople,” said one of their representatives. “A large number had been thrown out of employment by the action of a few.” The company then tried to go after Besant, threatening to sue her for libel. Besant was undeterred. “Cowards that they are!” thought Besant. “Why not at once sue me for libel and disprove my statements in open court if they can, instead of threatening to throw these children out into the streets?”

~

A meeting of the Fabian Society was held later that evening. Besant, Burrows, Sidney Webb, George Bernard Shaw, and Oscar Wilde were among the attendees gathered in the fashionable Willis’s Rooms to hear the well-known decorative artist, Walter Crane, speak on “Art Under Socialism.”[37] When it was learned that Crane was running late, Besant took to the platform to give an update of the matchgirl situation.

“No sign of the ‘legal attention’ announced in such hot haste by Mr. Theodore Bryant last week has yet reached me,” said Besant, “but Messrs. Bryant and May have not been idle. They apparently shirk the straightforward course of prosecuting me for libel, knowing full well that my statements are true and can be proved up to the hilt, and they fear the publicity that such a suit would give to their shameful treatment of the helpless girls they employ. Determined, however, to revenge themselves for the exposure of their iniquities, they have fallen on the girls themselves, selecting as victims three. In order to make the punishment of these as heavy as possible, they did not dismiss them at once, but kept them on for a week making their work very slack, and finally discharged one of the me with 2s. 8d. for her week’s wages, promising a second 3s. 6d., and a third 1s. 8d. These wages are to pay for food and rent for the week.

“It is hard to understand what kind of non-human beings they can be who can put into a woman-child’s hand 1s. 8d. as the price of her week’s labor, and then bid her go forth workless into the cruel streets. How can a man do this thing, and go home to his comfortable house, and perhaps to wife and child? What if his daughter hereafter should receive similar treatment at the hands of a man like himself? Or what if these trampled ones at last should revolt against their tyrants, and in some wild hour of popular fury pay back such mercy as they have received? Men speak of ‘the furies of the Revolution‘ with horror and loathing; but who dare judge harshly if such seed as Bryant and May are sowing yield similar harvest, and if the maddened poor are pitiless to these who have been pitiless to them?”

Besant then proposed a relief fund for the strikers.

Oscar Wilde c. 1889.

“We are often told that the poor are grateful for charity,” said Wilde, whimsically. “Some of them are, no doubt, but the best amongst the poor are never grateful. They are ungrateful, discontented, disobedient, and rebellious. They are quite right to be so. Charity they feel to be a ridiculously inadequate mode of partial restitution, or a sentimental dole, usually accompanied by some impertinent attempt on the part of the sentimentalist to tyrannise over their private lives. Why should they be grateful for the crumbs that fall from the rich man’s table?”[38]

Though his unpicturesque frock coat was more sombre than the bottle-green suits he wore in the past, Wilde’s colorful affect remained untarnished by convention. Nevertheless, anyone who expected a slender, decorated, woebegone aesthete, would have been disappointed by the good-humored—somewhat protuberant—personage in tweed trousers before them.

When Crane finally arrived, he delivered an address in which he stated that art could only reach its full development under Socialism.

Walter Crane.

“The movement initiated by Mr. William Morris,” said Crane, “and the gifted artists associated with him, to which we owe so much, began in a genuine return to honesty of purpose and to sincere design and sound workmanship, founded upon a study of good models in the past; but it was the outward and visible sign of an intellectual movement which has its eyes upon the future, and, like all revivifying and stimulating impulses in art, it is the offspring of hope and enthusiasm.

“Let us look to it that this English Renaissance of ours is not extinguished—that it does not fall utterly into the iron grasp of commercialism. We may figure art as the fair Andromeda chained to the rock of modern economic conditions, in danger from the all-devouring, desolating monster of gain, until the deliverer shall come.

“This is in sober truth the situation. Under our system of centralised industrial production, local art and industry are everywhere being dispossessed, and local characteristics and varieties are being fast obliterated. The machinery of trade forces prevailing patterns everywhere, and the mass of the world cannot pick and choose, or turn the stream of invention for their particular delight. It must accept the latest novelty of commerce, and content itself for all shortcomings with her assurance that it is ‘just out‘ and will certainly be ‘the fashion.‘ Thus it comes about that our cups and bowls, our tables and carpets, rather speak of the enterprise of a firm than historic traditions of a people, or the skill of a race of artists and craftsmen. The zeal to make things ‘pay‘ hath eaten us up, in the artistic sense. It is all very well to talk of informing with art the common accessories of life, to cultivate the handicrafts with enthusiasm, to distinguish ourselves by beauty of design and technical excellence among the nations of the earth, and after all, for a man to find that in proportion to the extra care, delicacy, and invention—in proportion as the craftsman works in the spirit of the artist, and is true to himself, without regard to trouble or time the more difficult will he find it to make his living.”[39]

“If every man is to be his own house-decorator,” said Wilde, “London—which is bad enough already—will become simply intolerable. The art of the future will clothe itself, not in works of form and color, but in literature.”

“But the masses love good art, too,” said Burrows.

George Bernard Shaw by Sir Emery Walker, 1888 (c/o National Portrait Gallery.)

“That just proves that the lower classes are following the insincere cant of the middle classes!” said Shaw. “If a middle-class audience were told that ‘Pop Goes the Weasel’ was a movement from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, they would go into ecstasies over it. I agree with Wilde—literature is the form which art will take.”

“It is to be regretted that a portion of our community should be practically in slavery, but to propose to solve the problem by enslaving the entire community is childish,” said Wilde. “All authority is quite degrading. It degrades those who exercise it, and it degrades those over whom it is exercised. The form of government that is most suitable to the artist is no government at all.”

“Very witty,” said Shaw, “but that has nothing whatever to do with Socialism.”[40]

UNION

The first meeting of the striking Matchgirls was held on the morning of July 8, in Mile End Waste. Two platforms were erected, with about 2,000 people in attendance.

“This meeting is called to protest against the tyranny of Messrs., Bryant and May towards the helpless girls in their employment,” said Burrows, “and to give support to them in their struggle.”

“The strike has already done much good,” said Besant, “for it has knit and bound the girls together, to try and oppose the sweating system. The firm has threatened to bring girls from Glasgow if the strikers did not accept their terms, but I think by timely intervention, they can prevent the Scotch girls from coming. I am of the opinion that everybody can do great good by pledging themselves not to use the matches of the firm.”

Besant was right, the strike had gained the support of the public. The list of names coming out in active support for the strikers was growing; Eleanor Marx, the daughter of Karl Marx, even joined the fight. The fund for relief was growing steadily. In addition to this organized effort, many Jewish tradesmen took it upon themselves to support the girls by donating several pounds among themselves, and providing the strikers with quantities of beer, bread, and cheese in the local pubs. A strike committee was soon formed which included Chapman, Cummings, and Naull. They were joined by five other women named Alice Francis, Kate Slater, Mary Driscoll, Jane Wakeling and Eliza Martin. Besant, meanwhile, penned an open letter to the shareholders of Bryant and May’s, many of whom, as Champion pointed out, were members of the clergy. The letter said in part:

Your feeling of anger at the exposure of the White Slavery on which you fatten is not the noble indignation of the man who has been betrayed into a wrong he knew not of, and who feels the intolerable stigma of a shame unwittingly incurred […] Your anger is against me who have exposed the wrong, instead of against those who have wrought it; you do not mind the bloodstains on your coins, but you would not that the world should see it rust. Shame on you, who so long as silence can be kept, are careless whence comes your gold; shame most of all on you who preach love and purity from your pulpits, and who practice the cruelest oppression, driving many a girl into a life of shame by paying her a wage on which she cannot live. You talk of a judgment on the other side of the grave. What judgment, suppose you, would a just Judge [give you?][41]

By the middle of July, with the assistance of the London Trades Council, the Strike Committee was able to make their case before the Directors of Bryant and May’s. On the evening of July 17th, a crowd of 600 gathered in the Great Assembly Hall, Mile End Road, to hear the result of the conference. The concessions were read aloud:

-

The firm will abolish all fines.

-

They will abolish all deductions made for paints, brushes, and stamps.

-

In order to compensate for the deductions for the racking work, the boys are to be put on piece work, with a view of facilitating the operations of the female workers, by which arrangement the girls may earn more money.

-

The packers, who had three-pence deducted from their wages because the paper was brought to them, will in future have that three-pence restored to them: but, in return, they will have to fetch their own paper. This will be a distinct gain to the girls, as they will have extra work, for which they will receive the pay themselves.

-

The firm will view with satisfaction the formation of an organized trade union among the employes in order that any just grievances they may have may m future be represented directly to the heads of the firm, and not, as in the past, through the foremen.

-

With regard to the important question of food, the girls had repeatedly complained that, owing to the ingredients used in the trade, they often sickened and felt distaste for their meals, which they considered injurious to health. On this point the firm yielded without hesitation, and will at once make arrangements to provide a separate room for the girls to take their food in.

-

No girl employe is to be discharged for any part they may have taken in the strike. The leaders will in no way be singled out on account of the present proceedings.[42]

Before the matchgirls decided on whether or not they would accept the terms, Besant addressed the assembly.

“A great deal of good has been done,” said Besant. “The terms far exceed my expectations. I think that you would do well to accept them.” A sea of admiring and grateful eyes gazed upon Besant and showered her with applause. “I am only too glad to feel that my humble efforts have been of such service,” she added.

Burrows, Besant, and the Matchgirls Strike Committee.

~

Days after the agreement was reached, Besant sent a letter to Stead: “When, oh when am I going to have one quiet hour with you my dear friend? I do so want it.”[43]

← →

THE AGONISED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS:

INTRO: CHARLEY.

I. WITCH TALES.

II. CARELESS WHENCE COMES YOUR GOLD.

III. THE TIMES ARE CHANGED.

IV. DENIZEN OF ETERNITY.

V. DOMOVOY.

VI. WITH LOW AND NEVER LIFTED HEAD.

VII. IMPERIAL GOTHIC.

VIII. THE SERVANT OF THE QUEEN.

IX. THE DWELLER ON THE THRESHOLD.

X. INDO-GOTHIC YOGA.

XI. INTENDED FROM ABOVE.

XII. THE SÉANCE ON CHEYNE ROW.

XIII. EVEN IN NEW ROOMS.

XIV. RUSSIA’S LEGENDARY LORE.

[APPENDICES]

SOURCES:

[1] Dunkley, C. (ed.) The Official Report of the Church Congress. Bemrose & Sons, Limited. London, England. (1892): 252-255.

[2] Pease, Edward Reynolds. The History of the Fabian Society. A.C. Fitfield. London, England. (1916): 34, 248-249.

[3] The Society for Psychical Research. Proceedings Of the Society for Psychical Research. Vol. III. Parts VIII & IX. Trübner And Co. London, England (1885): 248.

[4] Perdue, Jon B. The War of All the People: The Nexus of Latin American Radicalism and Middle Eastern Terrorism. Potomac Books. Washington, D.C. (2012): 97.

[5] Dunkley, C. (ed.) The Official Report of the Church Congress. Bemrose & Sons, Limited. London, England. (1887): 156-177.

[6] “Fabian Society and Socialist Notes.” Our Corner. Vol. XII. (July 1, 1888): 61-64.

[7] The “dialogue” from Wilberforce Bryant is from: “The Great Advertisers of the World.” The Pall Mall Budget. (London, England.) August 8, 1884.

[8] “Mrs. Annie Besant.” The Star-Gazette. (Elmira, New York) April 10, 1891; Stead, W.T. “Mrs. Annie Besant.” The Review of Reviews. Vol. IV, No. 22 (October 1891): 349-367.

[9] Williams, Montagu. Round London. MacMillan & Co. London, England. (1893): 17-29.

[10] “Dire Distress in London.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) April 14, 1891.

[11] Faivre, Antoine. “Renaissance Hermeticism and the Concept of Western Esotericism.” in Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times. Roel van den Broek and Wouter J. Hanegraaff. State University of New York Press. New York, New York. (1998): 109-123; Magee, Glenn Alexander. Hegel and the Hermetic Tradition. Cornell University Press. Ithaca, New York. (2008): 8; Al-Khalili, Jim. The House of Wisdom: How Arabic Science Saved Ancient Knowledge and Gave Us the Renaissance. Penguin Books. London, England. (2012): Chapter 4; Copenhaver, Brian P. Magic in Western Culture: From Antiquity to the Enlightenment. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, England. (2018): 261.

[12] Silver, Carole G. Strange and Secret Peoples: Fairies and Victorian Consciousness. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (2009): 38.

[13] Emsley, John. The Shocking History of Phosphorus: A Biography of the Devil’s Element. Macmillan. London, England. (2000): 73, 89-96.

[14] Besant, Annie. “White Slavery in London.” The Link. No. 21. (June 23, 1888.)

[15] “Meeting in Whitechapel.” The Eastern Post. (London, England) December 15, 1888.

[16] “Exploring East-End Slums.” The South Wales Echo. (Cardiff, Wales) July 22, 1889.

[17] Garfield, Robert J. “Among the Russian Jews in the East End.” The Quiver. Vol. XXX. (October 1895): 883-887.

[18] Williams, Henry Llewelyn. The Worker’s Industrial Index to London. “Labour News” Publishing Offices. London, England. (1881): 19; Buckland, Francis Trevelyan. Notes and Jottings from Animal Life. Smith, Elder, & Co. London, England. (1886): 372-375; Grant, A. “The Philanthropist’s Guide to London Shops.” The Pall Mall Budget. (London, England) August 4, 1887.

[19] Gorman, John B. A Tour Around the World in 1884. Southern Methodist Publishing House. Nashville, Tennessee. (1886): 168-171.

[20] Garfield, Robert J. “Sunday in Petticoat Lane.” The Quiver. Vol. XXXI. (May 1896): 584-587.

[21] Blech, Benjamin. Eyewitness to Jewish History. John Wiley & Sons. Hoboken, New Jersey. (2004): 208-209.

[22] “Judenhetze.” The Banner of Israel. Vol. V. No. 233. (June 15, 1881): 245-246.

[23] “Amongst the Jews at the East-End.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) August 7, 1885.

[24] Davies, H. Brooke. “Another Voice from the East End.” The Woman’s World. Vol. II. (1889): 64-66.

[25] “The Influx of Foreign Pauperism.” St. James’s Gazette. (London, England) December 23, 1886.

[26] W.S. “London Letter.” The Gravesend Reporter, North Kent and South Essex Advertiser. (Kent, England) February 20, 1886.

[27] Laister, J. “A Judenhetze Brewing in East London.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England.) February 18, 1886.

[28] “Notes.” St. James’s Gazette. (London, England) May 21, 1888.

[29] “An Autumn Evening in Whitechapel.” The Living Age. Vol. LXIV, No. 2314. (November 3, 1888): 313-315.

[30] Rumbelow, Donald. The Complete Jack the Ripper. Penguin. London, England. (2004): 12.

[31] Besant, Annie. The Law of Population: Its Consequences and Its Bearing Upon Human Conduct and Morals. Freethought Publishing Company. London, England. (1877): 36-37; Paul, Diane. “Eugenics and the Left.” Journal of the History of Ideas. Vol. XLV, No. 4. (October-December 1984): 567-590.

[32] “Sarah’s Success.” Truth. (London, England.) July 19, 1888.

[33] “Mrs. Annie Besant’s Mission.” The Sun. (New York, New York) April 10, 1891.

[34] “The Sweating System.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) June 28, 1888; “A Sweater’s Meeting.” The East London Observer. (London, England.) June 30, 1888.

[35] Descriptions of the strike are from: “Match Girls on Strike.” The Weekly Dispatch. (London, England.) July 8, 1888; “The Strike of Match Girls.” The Standard. (London, England.) July 9, 1888; “1,300 Match-Girls Still on Strike.” The Echo. (London, England.) July 11, 1888; “The Matchmakers on Strike.” The Daily News. (London, England.) July 13, 1888; “The Match Girls on Strike.” The East London Observer. (London, England.) July 14, 1888.

[36] “Heroines of the Hour.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England.) July 18, 1888; Besant, Annie. Annie Besant: An Autobiography. T. Fisher Unwin. London, England. (1893): 329-364.

[37] “The Other Side.” The Echo. (London, England.) July 7, 1888; “Daily Gossip.” The Echo. (London, England.) July 7, 1888; “Our London Correspondence.” The Glasgow Herald. (Glasgow, Scotland.) July 9, 1888; “Fabian Society and Socialist Notes.” Our Corner. Vol. XII. (August 1, 1888): 127-128.

[38] Wilde, Oscar. De Profundis and Other Writings. Penguin. London, England. (2015): “Introduction” by Hesketh Pearson, 9-16; “The Soul of Man Under Socialism,” 17-54.

[39] Crane, Walter. The Claims of Decorative Art. Houghton, Mifflin, and Company. Boston. Massachusetts. (1892): 118-119.

[40] Weintraub, Stanley; Shaw, George Bernard. Shaw: An Autobiography. Max Reinhardt. London, England. (1969): 307; Belford, Barbara. Oscar Wilde: A Certain Genius. Bloomsbury. London, England. (2000): 155.

[41] Besant, Annie. “To the Shareholders of the Bryant & May Company, Limited.” The Link. No. 24. (July 14, 1888.)

[42] “The Victory of the Match Girls.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England.) July 18, 1888.

[43] Brown, Stewart J. W. T. Stead: Nonconformist and Newspaper Prophet. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (2019): 83.