MUCKERS

~

A group of three buildings made up the “Muckers Camp” on the brow Reeders Hill, near Bessemer, Alabama.[1] The first was a kitchen and dining room. The second was a wash-house. The third was a large dormitory—where Irvine and the other laborers lived while working in the Muscoda Mines of the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company.

The original design for the dormitory was a collection of small rooms—but that plan was scrapped prematurely. It was now a warehouse of empty men, and the things empty men cared to carry. The floor was littered with trash, mostly discarded work clothes, old boots, and broken lamps. In the corner of the dormitory was a pyramid of fractured bedsteads, army blankets and soiled mattresses. Everything was painted red with the ore the miners scraped in from the belly of the earth. The idea of sleeping on the filthy bedding was repulsive to the men. They knew the work would be hard, and the living conditions deplorable, but they also knew there would be pay, and for that they kept silent. They were far from home, robbed of their honor, and stripped of their dignity. It did not matter who these men once were; their nationality was unimportant, their religion was unimportant, their history was unimportant. Sorrow was an equalizer. Every man thought the same thing as they fished their bedding from the cone of debris—they were unimportant. The outlook in the wash-house was more depressing. A long narrow trough, filled with red ore, ran through the center of the room, saturating the rags and old paper which lined the floor. Construction on the wash-house, like the dormitory, had been abandoned. The skeletal shower stalls were yet another broken promise, and they washed as best as they could.

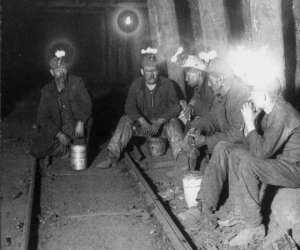

Interior of a mine, 1903. (c/o Library of Congress.)

After dinner that evening Irvine and his fellow-laborers went to the company store where they were fitted for their equipment. The name of every man was replaced with a number while employed by the company, so every man presented his number, and retrieved what was needed—heavy boots, lamps, and overalls. The credit system at the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company was generous. Goods were sold with a hundred percent markup, and since the company only paid wages once a month, this created a system of deepening debt and servitude. When the men returned to the dormitory, they were met by veteran miners who just finished their shift. They addressed the newcomers in Russian, Hungarian, Swedish and a multitude of other tongues. The inspection and classification of the newcomers was one of the few excitements of camp life. An old German miner produced a wheezy old accordion to unburden the monotony of night with songs from his homeland. The dormitory was unlit, save for the light of the lamp on each man’s cap. When they undressed before bed, each man extinguished the smoky, oily flicker, and removed their cap as the last act of the evening.

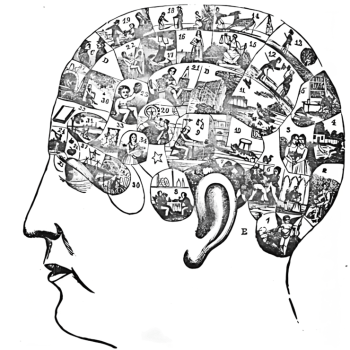

Memories of Ireland crept into Irvine’s mind as he settled into bed. He recalled his work in the mines when he was a boy, and he did not relish it. He remembered how the coal dust covered his skin like a “tight fitting garment.” Coal was part of every mouthful of food he ate in that fetid atmosphere. He had a powerful body, even in his youth, which shielded him from the greater dangers of the pit, but the labor was exhausting, and his face was always blistered from the hot oil that dripped from the lamp on his brow.[2]

Tennessee Coal and Iron Company.

The following morning, as the gray dawn lurched to the bare window, four of Irvine’s group got dressed and marched, deliberately, out of the camp. They were never seen again. For the men who remained, the day began with the ritual of the “mucker’s toilet.” The men first adjusted their lamp-caps with the flame still inside. Then they lit their pipes. Lastly, they got dressed. It was 5:30 in the morning. They sky was still dark. The shaggy, naked men, with heads smoky and ablaze, looked otherworldly. These creatures of the pit, however, were full of boisterous laughter. After a breakfast consisting of generous portions of pork, beans, potatoes, bread and coffee, the men hauled off to begin the work of the day. They traveled over the hill and into the valley, until they reached the entrances of the five mines. Each mine was marked with a tall puffing chimney. Each mine being a hive of man and machine.

Miners on a “skip.”

Irvine and two of his men, Franz, the Hungarian, and a German, whose name he had yet to remember, were perched at the tail end of the “skip” and commenced the half-mile descent into the red hills to disgorge the iron-ore with dynamite and hammer. The grade was a 45-degree angle, and the skip, attached to a powerful wire cable, went down like a ship in a gale. The aperture of the big square mouth of the mine, grew smaller as they ventured further into the mysteries of the earth. Soon they were enveloped in complete the darkness.

Birmingham Coal Mine (courtesy of Encyclopedia of Alabama.)

Every mine was like a small town, complete with main streets, side alleys, or “pockets” as they were called. These pockets were both “live” and “dead”—the dead being worked out and stripped. When the “skip” stopped at the first live pocket, Irvine and his compatriots jumped over the side, and on to a platform. They were approached by a short foreman who supervised their compartment, who directed them to the task of the day. The foreman was a driller, a man who used a steam-drill to plant holes for dynamite, as such, his arms were as hard as wire-cords, and his flesh was as taut as a drum. Irvine and his lot were muckers—miner’s helpers—who carried away the debris from the explosions. Each alley had similar crews.

The headlamps flitted like fireflies in the red mist. The air was filled with an admixture of sound—babbling water, chugging gulps of the pumps, and the puncturing clanks of the drill.

“Dynamite!” the foreman shouted.

Irvine and Franz ducked into a cleft with six old miners and stood ankle-deep in the muddy water alley for the impeding explosion.

BOOM!

It was like the deck of a warship when firing cannons from her broadside. The hills shivered from the explosion, and so did Franz. The older miners laughed at his fright. They spent years of their life working the mines. These human moles had accepted their life. Their skin, calloused and leathery, was normal for them—they had long-forgotten their mangled talons were once the hands of a child.

“Mule boy!” roared Irvine into an enclave in the rocks.

Philo the mule-boy appeared, clinging the tail of Emma, his mule.

The muckers took their sledge-hammers and went to work. Swing after swing, like a rubber ball, Irvine’s hammer bounced off the rocks.

“Turn that rock over,” the foreman shouted into Irvine’s ear. “Look for the grain!” The foreman turned the boulder on its side. “Give me that,” he said, grabbing Irvine’s hammer. With two strikes, the rock was splintered. He handed the hammer back to Irvine. The muckers quickly learned what they could, and instinct took care of the rest.

They worked doggedly, fast, and in silence. Sweat oozed from their bodies as they crushed cartfuls of stone. Hundreds of men, in other pockets, were doing the same—less bloody—but the work was the same. Every cart of ore blasted, the foreman received fifty cents and for running out each cart, the muckers got twenty cents—six cents each. It was a Hell of noise and dust! Endless was the sound of clattering pumps, rattling drillers, hissing steam, and roaring dynamite. It was the very limit of human strength and endurance. When it became too hot, Irvine removed his jacket. The others followed his lead. When it was still too hot, they removed their overalls. Eventually their work shirts were cast aside, leaving them only in their pants and undershirt.

“God damn your souls to hell,” the foreman shouted. “Why don’t you get a move on you—hey? You muckers ain’t goin’ t’ get ten cars out t’day if ye don’t mend yer licks.”

They “mended their licks,” and quickened their pace, but their cart soon slipped the track.

The foreman, reciting a poem of vulgarities, raced to help the muckers with the cart. He heaved his powerful body against the lever, and nearly lifted the car single-handedly.

The foreman’s lamp pressed against Irvine’s hand, but he was unable to let go.

“Move!” yelled Irvine.

“Too bad! Too bad!” the foreman said, as he dropped the truck.

Irvine’s examined his seared flesh, then stared the foreman in the eyes. “Look here!” he said, “if you will look as human as that again, you may burn the other hand!”

At 5 p.m. the muckers, with dozens of other men, squeezed into the “skip.” The hot breath of each panting member of squirming mass was felt on his neighbor. When the signal was given, the “skip” began its rattling ascent to the surface. An ecstatic, overwhelming sense of relief, washed over the men as they passed over the hill, and gazed upon the open sky.

The wash-house was crowded, but, to Irvine’s surprise, nobody was showering. Nevertheless, Irvine soaped himself and stood underneath the iron water-pipe—and waited.

“Are ye posin’ for yer photo, mister?” said an old miner.

“What’s the matter with the water?” asked Irvine.

“It’s got fits!”

Dinner was a brief affair. At a signal from the cook, the men rushed in and seized whatever was nearest. They dug in, heads down, with hands and jaws at top speed. Hardly a word was spoken.

As there were no property rights to pigs in Alabama, swine covered the landscape, littering in the tall dog-fennel, and rooting near the shanties. Little surprise, then, that pork was a staple menu item. The men had pork for breakfast, took their pork chops to the mines for lunch, and ate it every evening for dinner.

Irvine sat between an old Black miner named Ransom, and a German youth named Max who joked about the rancidity of the pig.

“What you guff about?” asked a burly steward, the acknowledged camp bully.

“Der shmell,” said the Max, gesturing to his nose, “its tick vit bad shmell.”

“Well, you shut your damn mouth, or I smash your damn head, see?”

Max laughed.

“No more servings for you,” said the steward, removing Max’s plate. “You come here for breakfast tomorrow and I smash your damn head!”

Max did not reply.

Nobody paid the situation any mind, they were too selfish and afraid to interfere.

The men smoked and talked as they made their way back to the dormitory.

“Who owns these pigs?” Irvine asked Ransom.

“One an’ another!” Ransom replied. “The gullies and the weeds are full of them. The steward finds them easy and cheap feeding.”

Though Irvine never had a taste for liquor before, he had a sudden and intense craving for it that night. It seemed, oddly enough, as though he had drunk it all his life.

He laid down on his soiled bed. He was far too tired for worry and thought. He fell fast asleep.

The next morning Irvine awoke to the protestations of a Norwegian mucker organizing a strike over the tainted pork eaten the night before. Five minutes later everyone in the shed gathered around the stove for an impromptu indignation meeting. Max, it was agreed, should go in first. If the steward threw him out, they would leave with him and go on strike.

Max was allowed to eat breakfast but was refused a lunch pail.

The men dropped theirs too, in solidarity, and marched together to the office.

The resulting investigation revealed that the steward was feeding the men his neighbor’s pork and charging it to the company. The steward was fired. Irvine and the men returned to the camp to celebrate with wrestling, and liquor.

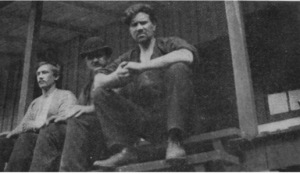

Irvine at the “Muckers” camp.

~

Operations in the mines ceased on Sundays. Irvine took the opportunity to visit Philo, the mule boy in Rat Hollow, a small town with a thousand inhabitants. It had no post-office, ditches instead of drains, wide gullies, but neither streets nor streetlamps. The only “modern convenience” was an old hydrant around which the children organizing imaginary fire companies and extinguishing imaginary flames.

“Philo,” asked Irvine, “where is the church?”

“The church is for Black folks,” said Philo. “If they want one, they travel for it.”

When Irvine returned to the camp, he found the men lounging around the stove, smoking, and sharing stories. The German sailor played his wheezy accordion in one corner, while in another corner a Russian soldier was singing a love song. It was Irvine’s last day with the muckers. Many of the gang had already left. It wasn’t a matter of wages or hours—it was a question of muck. Once in it, the men lived, moved, and had their whole being in it. Behind the red earth of Reeders Hill the sun was sitting low. A single yellow streak traced the purple horizon. The streak changed to amber and later crimson red. The purple clouds gave were replaced by black clouds and the stars began to appear. The muckers settled down for the night.

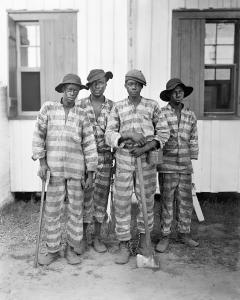

The following day Irvine paid a visit to the stockade where the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company had their convict-slave labor force. He was seedy-looking, with a full-grown beard and a dirty blue shirt and overalls. He approached the chaplain and revealed his true identity to gain admission to his night school.[3]

~

In 1862, during the American Civil War, an engineer from Alabama named John T. Milner and his associate, Frank Gilmer, convinced the Confederate government to let them build a blast furnace on Red Mountain, Jefferson County, and produce of iron for the war. The plant, built and operated by slaves, was the beginning of a vast industrial complex that would girdle the new city of Birmingham, Alabama. Milner and Gilmer then opened a mining complex that was operated with slave labor near Helena, Alabama.

During the war, Southern industrialists were pressured to increase production of existing mines, and to reopen idled businesses that could produce coal and iron. These southern industrialists assumed control of the Sewanee Mines, previously owned by a syndicate of Northern Investors, near Tracy City, Tennessee, which would later be known as the Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Co. Arthur S. Colyar, the manager of the company, immediately placed forty slaves in the Sewanee Mines.

A new form of institutionalized Black labor key component to the designs of Southern industrialists tasked with rebuilding the southern economy following the Civil War. The Thirteenth Amendment, adopted in 1865, abolished slavery, but had a special clause that allowed involuntary servitude as an acceptable punishment for “duly convicted” criminals. The southern economy was in ruins. White officials in southern states saw the convict-leasing of Black labor as a practical measure to side-step the financial burden of building prisons, and to ensure that Blacks remained in the lowest position in society. In the 1870s Alabama began “leasing” its Black prisoners as laborers for profit. Milner, the vanguard of this new idea for industrial forced labor, saw an opportunity to exploit Alabama’s convict-leasing program, and reinstate a new form of slavery. Milner acquired every Black body available and had them work in hellish coal operation of the Eureka Mines. Milner’s convict-slaves were subjugated to the most barbaric aspects of antebellum slavery. Black women were stripped naked and flayed, while hundreds of lice-ridden men, barely clothed, were chained, starved, and beaten. Nearly 20 percent of the Black convict-slaves died during the first two years of Alabama’s lease scheme. The mortality rate in the third year rose to 35 percent. In the fourth-year 45 percent of these men, nearly half, were killed.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Co. moved its base of operation to Alabama. Men like Colyar and Milner, true slavers, were instrumental in bridging the era of slavery with the New South. They both believed that subjugated Blacks were the key in creating a viable industrial sector in the Southern and check the encroaching influence of Northern capitalists. Southern Whites soon realized that the combination of bogus legal charges, and the threat of convict-slavery, was an incredibly powerful intimidation tactic over the newly-emancipated Black population; it effectively silenced the most influential leaders of the Black communities before they could reach any meaningful potential.[4]

Southern Convict-Slaves

The regulations concerning the living conditions of convict-slaves, on paper at least, required sanitary living quarters, nutritious food, and no cruel or excessive punishment. By 1906, however, guards of these mining operations were granted the power to chain prisoners, gun down escapees, and torture anyone who refused to submit. The only laws enforced with any regularity in this new institution of slavery, were those laws designed to ensure that further the dismal experience of the Black convict-slave. In Alabama companies were charged $150 fines for allowing any prisoner to escape. State law mandated that if a convict escaped while being transported to the mines, the Sheriff responsible had to serve out the prisoner’s sentence.

~

For three weeks Irvine lived among the men damned of the hellish stockade. He got the facts of the life there and became so depressed by what he saw that it became a daily struggle fighting off the hatred in his heart for the perpetrators of such an injustice. Eight hundred men, seven hundred of whom were Black. They were underfed and overworked; exploited and degraded in the most shameful ways imaginable—from officials in the boardroom, to the men with the whips and rifles. The smallest infraction meant the flogging like a galley slave. Women, too, were flogged, it didn’t matter to corporation. Tuberculosis finished what the whips and the labor left undone. Filthy living conditions in rotten sheds sent most of these men to their death, a destination that, to Irvine’s view, “they were better off.”

PEOPLE OF THE UNDERWORLD

I. INTERCOLLEGIATE SOCIALIST SOCIETY.

II. THE CRY OF PEONAGE.

III. MUCKERS.

IV. GALLAGHER’S HELL.

V. PUNK.

VI. SOUDAN.

VII. BOWERY.

VIII. “IT IS A BETTER FLAG THAN THE AMERICAN FLAG.”

IX. PENETRATING THE ASCENSION.

X. “THE UNIVERSE IS BASED ON THE SUBJECTION OF WOMAN.”

XI. PROGRESSIVE WOMAN SUFFRAGE UNION.

XII. THE CHRISTIAN SOCIALIST FELLOWSHIP.

XIII. THE ERUPTION OF THE END.

SOURCES:

[1] Burnett, Jason. Early Bessemer. Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, South Carolina. (2011): 26.

[2] Irvine, Alexander. “From the Bottom Up: An Unconventional Biography.” The World’s Work. Vol. XIV, No. 83. (September 1909): 379-389.

[3] Irvine, Alexander. “My Life In Peonage.” Appleton’s Magazine. Vol. IX, No. 6. (June 1907): 644-654; Irvine, Alexander. “My Life In Peonage Pt. II: A Week With The ‘Bull Of The Wood.’” Appleton’s Magazine. Vol. X, No. 1. (July 1907): 3-15; Irvine, Alexander. “My Life In Peonage Pt. III: The Kidnapping Of ‘Punk.’” Appleton’s Magazine. Vol. X, No. 2. (August 1907): 190-197; Irvine, Alexander. From the Bottom Up: The Life Story of Alexander Irvine. Gosset & Dunlop. New York, New York (1910): 256-273.

[4] Blackmon, Douglas A. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. Anchor Books. New York, New York (2009): 137-155. (E-Book.)