BOWERY

~

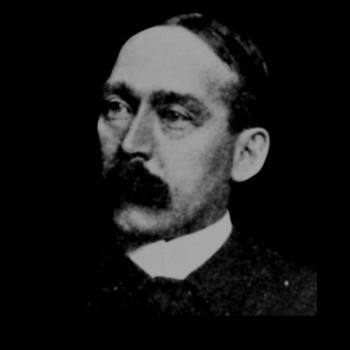

Percy Grant, the rector of the Ascension Church, was among the men in the crowd who came to hear Irvine lecture at the Washington Heights branch of the Y.M.C.A. on March 17.[1] He had come specifically to meet the speaker.[2] Grant had heard Irvine speak at the Interborough Shop and was impressed. It was engagement that Grant had been asked to participate but had declined. Principally because he thought it was such a very difficult thing to do in the right way.[3] Grant asked Charles F. Powlison (Religious Secretary of the Young Men’s Christian Association) about Irvine, and was told that, “He’s a splendid fellow, but he is utterly undependable. He is likely to blurt the truth out at any minute, and that’s something well, you know, in an institution like ours we have to be sure of a man.”[4] This made Grant like Irvine even more.

Percy Stickney Grant.

~

“The Bowery is one of the most unique thoroughfares of the world,” said Irvine, beginning his lecture. “The of the history cheap lodging houses, to which I was commissioned to carry the gospel, is one of the most interesting phases of the Bowery’s history. Ex-inspector Thomas Byrnes has described the lodging house of the Bowery as ‘a breeding place of crime.’ He probably did not know that the cheap lodging house had its origin in a philanthropic effort. It was in 1872, somewhere on the edge of a financial panic, that the first lodging house of this type was organized by two missionaries—Rev. Dr. A. F. Shauffler and the Rev. John Dooley. The Young Men’s Christian Association of the Bowery found a lot of young men attending its meetings who were homeless, and their endeavor to solve this problem resulted in the fitting up of a large dormitory on Spring Street. Somebody—Ex-inspector Byrnes says a Mr. Howe—saw a business opportunity in the philanthropy and copied the dormitory.

“There were from sixty to seventy of them on the Bowery when I began my work. These I visited every day of the week. There was a glamour and a fascination about it in the nighttime that held me in its grip as tightly as it did others. What a study were the faces—many of them pale, haggard; many of them painted! How sickly they looked under the white glare of the arc-lights that fizzled and sputtered overhead! Many of its shops have been ‘selling out below cost,’ for over twenty years.

“I did not confine myself to the Bowery but went to the small side streets around Chatham Square. They were also filled with cheap lodging houses. The lowest of these were called ‘bunk houses.’ Only one of the bunk houses remains. That is situated at No. 9 Mulberry Street. It is there today, little altered from the day I first entered it over twenty years ago. The price for lodging ranges from seven to fifteen cents, but fifteen cents was the more usual price.

Broome Street Tabernacle.

“My headquarters at first was the City Mission Church on Broome Street, called ‘The Broome Street Tabernacle,’ and to it I led thousands of weary feet. The minister at that time was the Rev. C. H. Tyndall, a splendid man with a modern mind; but I filled his tabernacle so full of the ‘Weary Willies of the Bowery’ that Mr. Tyndall revolted, and as I look back at the circumstance now, he was fully justified in his revolt. Mr. Tyndall was doing a more important work than I was, more fundamental and far-reaching. He was touching the family life of the community and he saw what I did not see—that our congregations could not be mixed; that my work was spoiling his. I did not see it then. I see it now. So I betook myself to another church, and this other church got a credit which it did not deserve, for they had no family life to touch. It was a church at Chatham Square, and its usefulness consisted in the fact that it was situated where it could catch the ebb and flow of the ‘tramp-tide.’

“I spent my afternoons in the lodging houses, pocket Bible in hand, going from man to man as they sat there, workless, homeless, dejected and in despair. I very soon found that there was one gospel they were looking for and willing to accept—it was the gospel of work; so, in order to meet the emergency, I became an employment agency. I became more than that. They needed clothing and food—and I became a junk store and a soup kitchen.

“After six months’ experience in the work, I had a story to tell. It was very vivid, and I could always touch the tear glands of a congregation with it and stir their hearts; so I went from church to church, uptown and out of town and anywhere, and told the story of my congregation on the Bowery. The result was not by any means a solution of my problem, nor of the tramp problem, but carloads of old clothes, and money to pay for lodgings. There was such a terrific tug at my heartstrings all the time that I never had two coats to my own back, or a change of clothing in hardly any department. As for money, I was, as they were, most of the time penniless! Everything I could beg or borrow went into the work.

“At the close of the first year, the results were rather discouraging. I got a number of men work, but very few had made good. Hundreds of men had been clothed, fed and lodged, but they had passed out of my reach. I knew not where they had gone. Scarcely one per cent, ever let me know even by a postal card what had become of them, or how they fared, and yet my work was called successful.

“Sunday afternoons, with a baby organ on my shoulder and a small group of converts and helpers following closely behind, I went down the Bowery and held meetings in about half a dozen houses. I did most of the speaking but urged the converts to tell their own stories at each service. I have said that I was never interfered with or molested in the work, and the following incident can hardly be called an exception. A broken-down prize fighter, slightly under the influence of liquor, tried to prevent us from holding a meeting one afternoon. I reasoned with him.

“‘You don’t seem to know who I am,’ he said. I confessed my ignorance. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘I’m Connelly, the prize fighter!’

“Then you’re what your profession calls a ‘bruiser.

“’Sure!’ he replied.

“Probably you are not aware, Mr. Connelly, that the Bible has something to say about bruisers.

Bowery. (NYPL)

“He explained that being a Roman Catholic, his Bible was different from mine, and he did not think there were any bruisers in his Bible.

“’Oh, you mistaken, Mr. Connelly. This is your Bible I have with me’—and I produced a

small Douey Bible, and turning over the pages in Genesis I read a passage which I thought might

appeal to him: ‘The seed of the woman shall bruise the serpent’s head.’ I suppose you know who the woman was, Connelly.’

“’The Holy Virgin?’ he inquired.

“’Yes; and the serpent is the Devil, and he has been pouring firewater into you and has been making you say things you would not otherwise say. As for the seed of the woman, that is Jesus Christ; and this Douey Bible of yours tells you that Jesus Christ is able to bruise the head of the old serpent in you, which is the Devil.’ That sounded rather reasonable to the retired prize fighter, and he quieted down and we proceeded with the service.

“The society for which I worked, occasionally sent down visitors to be shown around the lodging houses, and often I took them in there myself; but the thing grew very distasteful to me, for I never got hardened or calloused to the misery and sorrow of the situation, and it seemed to me eminently unfair to parade them.

New York Slum. (NYPL)

“About the last man I took around was Sir Walter Besant. I dined with him at the Brevoort House one night and took him around first to one of the bunk-houses and then to various others, and also into the tenement region around Cherry Street. ‘Keep close to me’ I told Besant as we entered the bunkhouse, ‘don’t linger.’ So we went to the top floor. The strips of canvas arranged in double tiers were full of lodgers. The floor was strewn with bodies—naked, half naked and fully clothed. We had to step over them to get to the other end. There was a stove in the middle of the room, and beside it, a dirty old lamp shed its yellow rays around, but by no means lighted the dormitory. The plumbing was open, and the odors coming there from and from the dirty, sweaty bodies of the lodgers and from the hot air of the stove—windows and doors being tightly closed—made the atmosphere stifling and suffocating. After stepping over the prostrate bodies from one end of the dormitory to the other, the novelist was almost overcome and when we got back to the door he begged to be taken to the open air. When we got to Chatham Square he said—‘Take me to a drugstore.’ Besant knew the underworld of London as few men of his generation knew it, but he had never seen anything quite so bestial, so debauched and so low as the bunk-house on Mulberry Street.”[5]

~

Following the lecture Grant approached Irvine and offered him a position on the Ascension staff conducting the Sunday evening service.[6]

“I cannot accept your offer,” said Irvine, “I am a Socialist.”

“I have immense respect and admiration for a man who has apparently solved this problem so successfully—who can talk to workingmen in their noon hour in a fashion to command their attendance in such large numbers.”[7]

“Dr. Grant, will the vestry endorse your call if they knew that I was a Socialist. I am not a man with Socialistic tendencies. I am a Socialist—a member of the party.”[8]

“What of it? You shall not be curbed in your views—nor in your expression of them,” said Grant. “Think about it.”[9]

PEOPLE OF THE UNDERWORLD

I. INTERCOLLEGIATE SOCIALIST SOCIETY.

II. THE CRY OF PEONAGE.

III. MUCKERS.

IV. GALLAGHER’S HELL.

V. PUNK.

VI. SOUDAN.

VII. BOWERY.

VIII. “IT IS A BETTER FLAG THAN THE AMERICAN FLAG.”

IX. PENETRATING THE ASCENSION.

X. “THE UNIVERSE IS BASED ON THE SUBJECTION OF WOMAN.”

XI. PROGRESSIVE WOMAN SUFFRAGE UNION.

XII. THE CHRISTIAN SOCIALIST FELLOWSHIP.

XIII. THE ERUPTION OF THE END.

SOURCES:

[1] “Y.M.C.A. Notes.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) March 9, 1907.

[2] “Grant Reviews His 30 Years as Rector.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) February 2, 1923.

[3] “Pulpit View Of Socialism.” The Sun. (New York, New York) April 19, 1908.

[4] Irvine, Alexander. A Fighting Parson: The Autobiography of Alexander Irvine. Little, Brown, and Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1930): 79-80.

[5] Irvine, Alexander. From the Bottom Up: The Life Story of Alexander Irvine. Gosset & Dunlop. New York, New York (1910): 90-96.

[6] “Grant Reviews His 30 Years as Rector.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) February 2, 1923.

[7] “Pulpit View Of Socialism.” The Sun. (New York, New York) April 19, 1908.

[8] Irvine, Alexander. From the Bottom Up: The Life Story of Alexander Irvine. Gosset & Dunlop. New York, New York (1910): 274; Irvine, Alexander. A Fighting Parson: The Autobiography of Alexander Irvine. Little, Brown, and Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1930): 79-80.

[9] “The People of the Underworld.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York) May 30, 1909; “General Items Of The Week.” The New York Tribune (New York, New York) October 19, 1907.