THE CRY OF PEONAGE

~

“Is this new form of slavery a reality?” That is the question Irvine asked himself as he read the sign: “100 Men Wanted.” It was written—in dozens of languages—on similar notices hanging in the shop windows along Greenwich Street. It was a lie masquerading as promise to seduce immigrants of every tongue. “If slavery still exists,” Irvine reasoned, “the best way to find it is by becoming a slave.” And the surest way of becoming a slave, Irvine thought, was to follow the “footprints” of the vanished men who had penetrated the mines and forests of the American South. The cry of peonage was the latest in a long list of societal injustices being brought to light. Press dispatches from the South told of the coercion of men, by whips and bloodhounds—of a new slavery built on ruins of the old. Irvine pulled a crumpled, week-old newspaper clipping from the pocket of his overalls, and re-read the contents:

White Slave Drivers Held.

Pensacola, Florida, August 3, 1906—The investigation of peonage at the Jackson Lumber Company camps at Lockhart, by a United States Commissioner today resulted in three men being held to the United States Court. They are Robert Gallagher, the superintendent, and W.M. Grace and Oscar Sandor, employees of the company. Many witnesses were examined, and all testified that men had been beaten and ill-treated at the camps. But the climax came when Manuel Jardemski, who had been brought from New York with others, was placed on the stand, weak and suffering from bruises on his body and burning with fever. He had been beaten with whips, struck in the face with clenched fists and kicked in the abdomen and about the body. He pointed out to Gallagher as the man who had inflicted most of the punishment. So pitiable was his condition that a purse was made up to place him in the hospital. Mrs. Mary Paul Jones and Mrs. Gibson, living near Laurel Hill, swore they had seen men overtake a foreigner near their house with hounds, and while one covered him with a revolver, another beat him with a whip.[1]

“Next!”

The labor agent at the muscle-market sized up Irvine. Dressed in a pair of overalls, sporting an unkempt beard, and carrying a bright yellow bundle in his hand, Irvine certainly looked the part of a laborer.

“Nationality?” the agent asked.

“Irish,” Irvine replied in truth.

“Nix!” the agent said, raising up his hands.

“Why not?” Irvine asked.

“Agh!” grunted the agent. “Irishmen are no good—they kick hell all the time—everywhere they go!”

There was no use protesting, Irvine knew this, and so he took his leave.

“Psst!”

Irvine turned around to find the agent’s understudy.

“Hey mac, want some advice?”

“Sure,” replied Irvine, with concealed suspicion.

“Come back in a few days with a fake accent,” said the understudy. “Do you know what a Finnish accent sounds like?”

“No.”

“Neither does the agent—from now on you’re ‘John the Finn’ got it?”

“Got it,” said Irvine with an appreciative laugh.

Muscle Market.

On the understudy’s advice, Irvine came back as “John the Finn,” and secured employment down South at the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company.

He was grouped into a band of immigrant workers—Greek, Hungarian, Italian, and Polish—who were being shipped to various parts of the South. All of them wore large placards pinned to their chests to save both the porters and the public the trouble of asking them any questions. Irvine’s placard read “Southern Railway,” which indicated his direction.

They were inspected at every depot on the journey by curious crowds, and labor agents who tried to poach them from the agent in charge. One poacher approached Irvine with a bottle of whisky, as a sign of good fellowship. “Want a pull, Johnny?” he said. “How’s about you come work at our camp? You’ll get $1.50 a day, and free board—we got saloons nearby with plenty of women.”

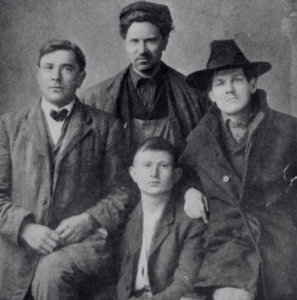

Irvine and three other laborers as they left Greenwich Street.

At Portsmouth, Virginia, the porter, a large Black man, addressed the party mostly by signs, and led them into the car. Once inside, the porter arranged them in their seats, pressing his hands on some of their shoulders when necessary—and not necessary. A Black woman at the window seat next to Irvine anxiously tossed her head, and gave him nervous look as if to say: “What are you doing here?”

Irvine scanned the compartment and saw a large yellow card marked “Colored,” indicating that they were in a “Jim Crow Car.”

When the train left the depot, Irvine approached the porter. “Haven’t you a law in Virginia on the separation of the races?”

“There sure is, boss—but you ain’t no race.” The porter grinned. “You just a dagoe, ain’t you?”

The reason for the both the question, and the answer, skirted the issue of not only race—but of penalty. Section 6 of the 1900 Virginia race laws stated:

Be in further enacted, that any conductor or manager on any railroad who shall fail or refuse to carry out the provisions of section five of this act shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon indictment and conviction thereof, shall be fined not less than twenty-five nor more than fifty dollars for each offense.[2]

~

The first of these racially segregated “Jim Crow Cars” were introduced in New England in 1840 by the Eastern Railroad Company of Massachusetts.[3] The name derived from the titular character of one of the earliest minstrel songs and used as a pejorative by Whites towards Black people.[4] After the American Civil War, the former Confederate States drafted legislation that promoted racial segregation that, by the end of the 19th century, would come to be known as “Jim Crow Laws.” Two significant developments in the policy of separation were implemented in the South in the summer of 1906. In Savannah, Georgia, ordinances for segregated seating on transportation went into effect for the first time, which caused protestations from Black community, and many refusing to ride in the cars at all. Montgomery, Alabama went a step further, and demanded not just segregated seating, but entirely separate “Jim Crow Cars” for Blacks. In no other relationship, besides public transportation, did Blacks share a space which came anywhere near close to an equal footing with Whites. Naturally, the subject of the inferior accommodations of the “Jim Crow Cars,” and their treatment on them, was greatly, and bitterly, discussed in the Black community.[5]

~

At Atlanta Irvine’s party changed cars and were once again driven into the “Jim Crow Car.” This time Irvine took another approach. The conductor dressed in broadcloth and covered with gold lace, strolled into their car like the captain of a ship, and collected the block ticket for their gang from the boss. When the conductor returned Irvine stepped into the aisle in front of him to block his passage.

“Pardon me, sir,” said Irvine, “isn’t there a law in Georgia on the separation of the races?”

The conductor silently removed the glasses from his nose and stared at Irvine. With a sharp pivot he walked to the end of the car, removed the placard which read “Colored,” and reversed it so it now read “White.”[6]

PEOPLE OF THE UNDERWORLD

I. INTERCOLLEGIATE SOCIALIST SOCIETY.

II. THE CRY OF PEONAGE.

III. MUCKERS.

IV. GALLAGHER’S HELL.

V. PUNK.

VI. SOUDAN.

VII. BOWERY.

VIII. “IT IS A BETTER FLAG THAN THE AMERICAN FLAG.”

IX. PENETRATING THE ASCENSION.

X. “THE UNIVERSE IS BASED ON THE SUBJECTION OF WOMAN.”

XI. PROGRESSIVE WOMAN SUFFRAGE UNION.

XII. THE CHRISTIAN SOCIALIST FELLOWSHIP.

XIII. THE ERUPTION OF THE END.

SOURCES:

[1] “White Slave Driver’s Held.” The Sun. (New York, New York) August 4, 1906.

[2] Boys, Richard Henry. The Separate, or “Jim Crow” Car Laws: Or Legislative Enactments of Fourteen Southern States, Together with the Report and Order of the Interstate Commerce Commission to Segregate Negro Or “colored” Passengers on Railroad Trains and in Railroad Stations. National Baptist Publishing Board. Nashville, Tennessee (1909): 55-57.

[3] “Eastern Rail-Road Outrage.” The Liberator. (Boston, Massachusetts) November 4, 1841.

[4] “Jim Crow.” The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia: A Work of Universal Reference in All Departments of Knowledge with a New Atlas of the World. Vol. IV. The Century Co. New York, New York. (1906): 3233.

[5] Baker, Ray Stannard. “Following The Color Line.” The American Magazine. Vol. LXIV, No. 1. (May 1907): 3-18.

[6] Irvine, Alexander. “My Life In Peonage.” Appleton’s Magazine. Vol. IX, No. 6. (June 1907): 644-654; Irvine, Alexander. “My Life In Peonage Pt. II: A Week With The ‘Bull Of The Wood.’” Appleton’s Magazine. Vol. X, No. 1. (July 1907): 3-15; Irvine, Alexander. “My Life In Peonage Pt. III: The Kidnapping Of ‘Punk.’” Appleton’s Magazine. Vol. X, No. 2. (August 1907): 190-197; Irvine, Alexander. From the Bottom Up: The Life Story of Alexander Irvine. Gosset & Dunlop. New York, New York (1910): 256-273.