INTERCOLLEGIATE SOCIALIST SOCIETY

~

Alexander Irvine rubbed his large, chapped, hands together as he walked along Wooster Square. “The Christian organizations, being wholly dependent upon the gains of the capitalists cannot afford to even appear to sanction a lecture on Socialism.” It was late January 1906, and Irvine’s breath was as steamy as his mood. “If it were Christian Science or Buddhism or a minstrel show, or anything of that sort, it would pass muster,” he thought to himself.

Irvine, acting in his capacity as representative for the Connecticut State Committee of Socialists, invited Jack London to come to speak at New Haven. London had just finished speaking at Harvard, and though his calendar was full, he dropped his smaller engagements for the opportunity to speak at Yale. The problem, which Irvine failed to mention, was that every venue in New Haven was booked. In desperation, Irvine called on a Yale student who was canvassing the subject of Socialism independent of the New Haven Local. Together they hatched a plan.

“London is a literary man,” said Irvine. “Yale has probably heard of him.”

Vanderbilt Hall, c. 1905.

The student talked the matter over with an officer of the Yale Union (a debating society,) who was receptive to the idea. Irvine was soon called into conference in Vanderbilt Hall for final arrangements.

“They say London is socialistically inclined, Mr. Irvine,” said the officer of the Yale Union.

“Rather,” Irvine replied.

“Well, I suppose we’ll have to take our chances,” said the officer. “There is no money in the Yale Union treasury, and the hall will cost fifty dollars.”

“I guarantee the hall rent, advertising, etc.,” said Irvine, “provided we might charge an admission fee of ten cents.”

“Agreed.”

“In case of a frost or a failure, I promise to make good the deficiency,” said Irvine. “As compensation for ‘risk involved,’ I will take the surplus, if there was any.”

The officer nodded in agreement, but was still apprehensive over the attitude of Yale President, Arthur Twining Hadley. “Of course, if London says nothing about Socialism it’ll be alright.”

Russia was in the midst of a revolution. Weeks earlier nearly 1,500 men, women, and children were killed in Moscow during the failed joint-uprising of the city’s Bolsheviks, Mensheviks, and Socialist Revolutionaries cooked up in the flat of poet, Maxim Gorky.

“Of course,” Irvine softly echoed. “Will you introduce him?”

“Certainly,” said the officer. “Do you know his topic?”

“Yes, I do.”

“What is it?”

“He calls it ‘The Coming Crisis.'”

“Social I suppose, eh?”

“Yes, it is a suggested remedy for a lot of our troubles.”

“Ah well, er, has he really a socialistic tendency?“

“A tendency did you say? Well, brother, if when you hear this speech, you call it a ‘tendency,’ I would like to know what the genuine article is!”

Lee McClung.

The following morning the Socialist student met with the Yale Treasurer, Lee McClung.

“I do not know Mr. Irving or Mr. London,” said McClung. “I will have to consult the advice of Professor Phelps.”

“Yale is a university, not a monastery,” said William Lyon Phelps, who taught the first university course in America on the modern novel. “Besides, Jack London is one of the most distinguished men in the world.”

Upon Phelps’s advice, McClung agreed to host the event at Woolsey Hall.

The advertisements began immediately. Every factory, shop, and tree in New Haven soon bore a dodger with the mysterious inscription written in red letters: “Jack London at Woolsey Hall.”

~

A few weeks earlier, on Sunday, December 17, 1905, Jack London “author, war correspondent, lecturer, socialist, and ex-tramp,” arrived in Boston. With him was Charmian Kittredge, whom he married a month earlier. Looking at the Boston Commons he recalled the last time he was in the city. It was 1894; he landed on a freight train that pulled into the Boston and Albany yards at two o’clock in the morning and went to the Common. Penniless, London was compelled to borrow some money from a policeman and wandered the streets until he found a luncheon where he could eat. When he started back for the Common to sleep on a bench, he lost his way. Though he traveled in many foreign lands, it was the only time in his life that he couldn’t find his way.[1]

View of Boston Common from the State House. (Boston Public Library.)

Girdling the Charles Street side of Common were an assortment of “new religions,” each of which had a charismatic salesman who delivered a fine-crafted pitch.[2] There were the Society of Angel Dancers, The Holy Ghost and Us Society, and the homegrown adherents of Mary Baker Eddy’s philosophy, the Christian Scientists, who were celebrating the renewed work on the extension of the Christian Science “Mother Church” on Massachusetts Ave. Mormon apostles professed their belief that the Garden of Eden was in America, while other denominations claimed proof that it was once Atlantis—the latter belief having gained currency with the recent findings of Harvard archaeologist, Alfred Tozzer, which presented “a new set of ruins,” that shed new light on “the history of the ancient Maya Indians.”[3] There were the Mazdaznans, a Zoroastrian-inspired group which claimed among its members Louis Potter, a cousin of Henry C. Potter, Episcopal Bishop of the Diocese of New York.[4] Perhaps the newest of the new religions were the Zeteticists, preachers of the Lady Blount’s flat-earth movement who claimed, “The solar system is a romance and gravitation a delusion!”[5]

The Mother Church Extension, December 19, 1905. (Mary Baker Eddy Library.)

The most popular of all these preachers, however, were the Socialists. It was said that “next to the religious doctrines, Socialism of one kind and another,” was the most prevalent kind of preaching in the Common. According to William James, Socialism was a religious doctrine, and for them, Marx was a “saint.” James writes:

Not only does [the Saint’s] vision of a better world console us for the generally prevailing prose and barrenness; but even when on the whole we have to confess him ill adapted, he makes some converts, and the environment gets better for his ministry. He is an effective ferment of goodness, a slow transmuter of the earthly into a more heavenly order. In this respect the Utopian dreams of social justice in which many contemporary Socialists and Anarchists indulge are, in spite of their impracticability and non-adaptation to present environmental conditions, analogous to the saint’s belief in an existent kingdom of heaven. They help to break the edge of the general reign of hardness and are slow leavens of a better order.[6]

London described his own “conversion” to Socialism in his 1905 book, War of the Classes. “I was now a Socialist,” London wrote. “I had been reborn, but not renamed, and I was running around to find out what manner of thing I was.”[7] The author of The Call of the Wild and The Sea-Wolf, was in Boston, in fact, as part of his cross-country tour to spread the “gospel” of Socialism, with the intention of adding a Harvard Chapter to The Intercollegiate Socialist Society. (I.S.S.) Six months earlier, in June 1905, a call was issued “to college men and women to form a body for the purpose of studying socialism.” Their letter stated:

In the opinion of the undersigned, the recent remarkable increase in the socialist vote in America should serve as an indication to the educated men and women in the country that socialism is a thing concerning which it is no longer wise to be indifferent. The undersigned, regarding its aims and fundamental principles with sympathy, and believing that in them will ultimately be found the remedy for many far reaching economic evils, propose organizing an association to be known as the Intercollegiate Socialist Society for the purpose of promoting an intelligent interest in socialism among college men, graduate and undergraduate, through the formation of study clubs in the colleges and universities and the encouraging of all legitimate endeavors to awaken an interest in socialism among the educated men and women of the country.[8]

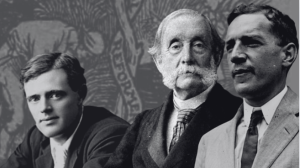

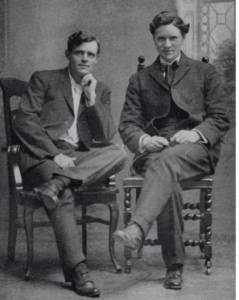

London, Higginson, and Sinclair.

The call was signed by, among others, Jack London, Upton Sinclair, and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a Unitarian minister from the Harvard Divinity School, who, as a member of the “Secret Six,” aided fellow-abolitionist, John Brown.

It was not until the autumn of 1905 that the I.S.S. formally began its career. On September 12, a hundred collegians gathered in the “rather dingy room” of Peck’s Restaurant on Fulton Street in New York City. After a chaotic session with Upton Sinclair as chief spokesman, an organization was quickly formed. Jack London was elected president and Sinclair was elected vice-president. It was a rough start. Sinclair was busy writing The Jungle, a serialized work which appeared in the socialist paper, Appeal to Reason. The most successful efforts thus far were London’s lecture tour. It began with his address, “Revolution,” at the University of California “which shocked the serenity of the student life in that Pacific Coast university.”

Before Boston London spoke in New York’s Grand Central Palace under the auspices of the I.S.S. and made a strong impression on the large gathering. As a template on how to proceed with planting the seeds of the I.S.S. in the universities, London and his cohorts turned to a speech delivered by the Italian Socialist, Enrico Ferri:

We should introduce Socialism into the students’ minds as a part of science, as the logical and necessary culmination of the biological and sociological sciences,” he said. “No need of making a direct propaganda which would frighten many of the listeners. Without pronouncing the word Socialism once a year, I make two-thirds of our students conscious Socialists.[9]

The I.S.S. had reason to be optimistic about the prospect of Harvard’s receptivity to Socialism. Francis Greenwood Peabody, the Dean of Harvard Divinity School, in dealing with the Gospel of Jesus, was compelled to engage with the increasingly-popular Marxist literature of his day.

Francis Greenwood Peabody.

Peabody re-contextualized the apocalyptic prophecies relating to the Kingdom of God and the End Times as a material, not spiritual, reality, thereby salvaging the consistency of the Christian Biblical narrative. In 1900 Peabody published Jesus Christ and the Social Question, one of the founding documents in the literature of what would come to be known as the Social Gospel. In it, Peabody states:

It is not enough to say that the socialist program is indifferent to religion. It undertakes to provide a substitute for religion. It is a religion, so far as religion is represented by a philosophy of life, to which men give themselves with passionate attachment. It sets itself against Christianity […] It offers itself as an alternative to the Christian religion. [It is] not merely a new economic and social program. but proposes to compete with Christianity in offering a comprehensive creed

We find, then, a gulf of alienation and misinterpretation lying between the social movement and the Christian religion—a gulf so wide and deep as to recall the judgment of Schopenhauer, that Christianity, in its real attitude toward the world, is absolutely remote from the spirit of the modern age. […] What reason has the Christian Church for existing, many persons are now asking, if it is not to have a part in that shaping of a better world which at the same time is the aim of the social movement? What was the gospel of Jesus if it was not, as he himself called it, a gospel for the poor, the blind, the prisoners, and the broken hearted? Is it possible that the social movement, which so often seems remote from, or even hostile to, the work of the Christian religion, may be in reality nothing else than a modern expansion of that religion? May it not come to pass that the solution of social question shall be found in the principles of the Christian religion? And is it not, on the other hand, evident that the only test of the religion which the modern world will regard as adequate, is its applicability to the solution of the social question? Must we not […] either socialize Christianity or Christianize socialism?[10]

Peabody’s scholarship would have other consequences. His popular course, Philosophy 5, (known colloquially as “Peabo’s drainage, drunkenness, and divorce,”) explored a constellation of issues surrounding labor, prison reform, temperance, charity, and the institution of marriage.[11] This gave rise to the field of Social Work as a profession. Relief work belonged, traditionally, to the purview of the churches, with groups like the Charity Organization Society aiding those in need. With the decline of church attendance, however, such organizations could not survive, and so the domain of morality was outsourced to the state. In 1904 Harvard collaborated with nearby Simmons College to create the Harvard-Simmons Institute, “A School for Social Workers,” as The Boston Evening Transcript stated in May 1905, was a “fitting culmination to Professor Peabody’s twenty years of teaching in Social Ethics.”[12] At Harvard’s Commencement ceremony in 1905, Harvard received a gift of $100,000 from an anonymous benefactor for the endowment of the Department of the Ethics of Social Questions and was to be known as the “Francis Greenwood Peabody Endowment Fund.”[13]

Exterior of Harvard Union.

On December 21, 1905, London enraptured a full house in The Harvard Union for over two hours. “In the university world I find the men clean and noble, but not alive,” said London. “But life is alive, and we who are live creatures and alive should deal with it with passion!”[14]

~

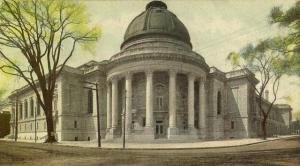

Woolsey Hall was crowded on the evening of January 26, 1906. There were a hundred professors, ten times as many students, hundreds of workingmen, and hundreds of Socialists members of the party were there—but they were so overwhelmed by the “Bourgeois atmosphere” that none made the slightest attempt to applaud during the entirety of the lecture.

London and Irvine.

“I speak tonight on behalf of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society,” London began. “This is a society formed, not for the purpose of getting Socialist votes in the colleges and universities of the United States, but for the purpose of starting in the various colleges an intelligent study of Socialism. It is to be deplored that so far in the United States there has been no such intelligent study of Socialism.

“Socialism is something that has been tabooed, or else it has been misunderstood, misinterpreted, misconstrued. For instance, I know, I am confident that there is no man in this audience tonight who knows anything about Socialism who will say that its aim is anything else and anything less than noble. Yet, reading the capitalist press of the United States, one constantly has impressed upon him the feeling that Socialism is something in aim that is not noble.

“Socialism is nothing more nor less than a science and a philosophy that deals with the human and attempts to make a better world for the human; attempts to get a more rational organization of society than we have today. And Socialism is clean, noble, and alive. I, for instance, was born in the working class. I lived on a ranch in California in a state of sordidness and wretchedness. I did not have always enough to eat. I am trying to give this little bit of biography in order to make you understand my own approach to Socialism. I had no outlook but what you might call an up-look. Above me towered the colossal edifice of society, and I felt that up there were beautiful clothes; men wore boiled shirts, and women were beautifully gowned, and there were there all the good things to eat and plenty of them. So much for the flesh. I also felt that up there I would find things of the spirit, clean and noble living and deeds and ideals, and I resolved to climb up there. But it was my destiny, before I climbed, to go down. Starting in the working class, I went down into what Gorky calls the ‘cellar of society,’ down into the abyss, down into the charnel houses of civilization. This is something it is not considered good form to speak about, but I went down there and lived, and ‘sweated my bloody sweats’ in jails and prisons of various sorts, digging my way, and starving and looking at society from an entirely new point of view. I found there, it is true, all the inefficient of society, the men who were born failures, but I found there also, and in great numbers, the men who had been worked out by society, the men who sold their muscles.

Woolsey Hall, Yale.

“Now, as I looked, I learned a lesson, and that was that it was not the thing for me to do to remain what I had been, that is, a seller of muscle. I saw that all men bought and sold commodities, and that the most unfortunate of sellers was the man who sold muscle, because his was the one stock that did not renew itself. The shoe merchant sold shoes, and as fast as he sold shoes, he put in more shoes in his store. He constantly replenished his stock. The brain merchant did the same thing. As fast as he sold his brain, he replenished it. But the man who sold nothing but muscle, each day reduced his stock of muscle, until at last when he was forty or forty-five or fifty years of age, he had sold out his complete stock of muscle, and as he had no children to take care of him, no children fortunately situated, he went down into the shambles, down into the abyss, and perished. Whereas, the man who sold brain, when he was forty-five or fifty or fifty-five or sixty, he had a finer stock, a fuller stock, than any time in his life before, and he was receiving a higher price for his wares. And so, I resolved to become a seller of brain. When I succeeded in becoming a merchant of brain, I found that society opened its doors to me higher up, and I went up there expecting to get in with people who lived lives that were clean, noble, and alive. I fully expected that, and I, who had come through all this material want and wretchedness, came in on the comfortable parlor floor of society and was appalled by the gross and selfish materialism I found there. I did not find life clean, noble, and alive.

“In the business world well, why should I stop; why should I take two minutes to tell you of the business world. You know the base side of the business world today. Accounts are given in all our daily papers and all our magazines of the rottenness and betrayal and crime that pertains to the business world. I found there nothing that was clean, noble, and alive. And in the political world I found the same thing. I found our political leaders were men who were mastered by machine bosses, who obeyed the dictates of machine bosses who were themselves bought and sold, who rode on railroad passes and who sold legislation to capitalist-purchasers of capitalist legislation.

“I find the conservatism and unconcern of the American university in the great mass of the American people, the people who are suffering, the people who are in want. And so, I became interested in an attempt to arouse in the minds of the young men of our universities an interest in the study of Socialism. Of course, such is my vanity it is only human vanity that I personally believe that practically every young man who has noble impulses, who wants to go in for something that is clean, noble, and alive that practically every young man who will study Socialism, its science and philosophy, will become a convert to its doctrines. Such is my belief…

“We do not desire merely to make converts, to have our young men of the universities all become Socialists. We do not expect that but want them to raise their voices for or against. If they cannot fight for us, we want them to fight against us of course, sincerely fight against us, believing that right conduct lies in combating Socialism because Socialism is a great growing force. There are throughout the civilized world 7,00,000 Socialists, organized in a great international movement. Their purposes are the destruction of bourgeois society, the doing away with the ownership of capital and with patriotism, in brief, the overthrow of existing society. We will be content with nothing less than all power, with possession of the whole world. We socialists will wrest the power from the present rulers. By war if necessary. Stop us if you can! If the people object to our program because of the constitution, then to hell with the constitution,” London declared, before an audience of 3,000 Yale men and their friends in Woolsey Hall—the great Yale amphitheater. “Yes, to hell with the constitution,” re reiterated. The capitalists are in the minority,” he said. “We are in the majority. All capitalists are bad, and all workingmen are good. President Roosevelt is frightened by our revolution. He says that class war is the greatest danger to the country. Class war is our watchword.”[15]

⸻

“London’s talk was the greatest intellectual stimulus Yale has had in many years,” a Yale professor told Irvine a few days after London left. “I sincerely hope that London will return and expound the Socialist program in the same hall.”

For over twenty years Irvine had been a contributor to newspapers and religious periodicals, but it was not until he met Jack London did it ever occur to him that he could make a living by the pen.[16]

PEOPLE OF THE UNDERWORLD

I. INTERCOLLEGIATE SOCIALIST SOCIETY.

II. THE CRY OF PEONAGE.

III. MUCKERS.

IV. GALLAGHER’S HELL.

V. PUNK.

VI. SOUDAN.

VII. BOWERY.

VIII. “IT IS A BETTER FLAG THAN THE AMERICAN FLAG.”

IX. PENETRATING THE ASCENSION.

X. “THE UNIVERSE IS BASED ON THE SUBJECTION OF WOMAN.”

XI. PROGRESSIVE WOMAN SUFFRAGE UNION.

XII. THE CHRISTIAN SOCIALIST FELLOWSHIP.

XIII. THE ERUPTION OF THE END.

SOURCES:

[1] “Guest In Newton.” The Boston Daily Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 18, 1905; “Noted Writer Reaches Boston.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 18, 1905.

[2] “The People of the Parks.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) June 5, 1905; Kirby, Louis Paul. “Wealth of New Religions.” Public Opinion. Vol. XXXIX, No. 5. (July 29, 1905): 137-140.

[3] “The Newest Ruins.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) May 20, 1905.

[4] Zar-Adusht-Hanish, Otoman. Inner Studies: A Course of Twelve Lessons. Sun-Worshiper Publishing Company. Chicago, Illinois. (1902): 89.

[5] “This Earth is Flat, Says Lady Blount.” The Buffalo News. (Buffalo, New York) March 26, 1905.

[6] James, William. The Varieties of Religious Experience. Longmans, Green, And Co. New York, New York. (1902): 151, 359-360.

[7] London, Jack. War of the Classes. The Regent Press. New York, New York. (1905): 278.

[8] “Mr. Jack London’s Socialistic Observations.” The Sun. (New York, New York) June 3, 1905; “To Study Socialism.” The Sun. (New York, New York) June 4, 1905.

[9] Creelman, James. “America’s Trouble-Makers.” Pearson’s Magazine. Vol. XX, No. 1. (July 1908): 3-28.

[10] Peabody, Francis Greenwood. Jesus Christ and the Social Question. The MacMillan Co. New York, New York. (1900): 19-21.

[11] Reynolds, Jr., Levering. “The Later Years (1880-1953.)” The Harvard Divinity School. George Hunston Williams. (ed.) The Beacon Press. Boston, Massachusetts. (1954): 165-229.

[12] “Training Social Workers.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) May 5, 1905.

[13] Merriman, R.B. “The Summer Quarter.” The Harvard Graduates’ Magazine. Vol. XIV, No. 53. (September 1905): 43-49.

[14] “To Students.” The Boston Daily Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 22, 1905; “Jack London at Harvard.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 22, 1905.

[15] “London Cries, To H—With Constitution.” The Inter-Ocean. (Chicago, Illinois) January 28, 1906; Irvine, Alexander. Jack London At Yale. The Connecticut State Committee & Printed at the Ariel Press. Westwood, Massachusetts. (1906.)

[16] Irvine, Alexander. From the Bottom Up: The Life Story of Alexander Irvine. Gosset & Dunlop. New York, New York (1910): 250-255.