WRECK OF THE HEREFORD

In the spring of 1907 Arthur “Punk” Buckley paid Irvine a surprise visit in New York, and told him what had happened during the intervening weeks since they last saw one another in Florida. After the trial the peons stood by each other until all were down at the same dead level of poverty. Then they separated and Arthur went to sea on March 16, 1907 on the Norwegian square-rigged bark Hereford, bound for Buenos Aires with a cargo of lumber.[1]

Before he got his “sea legs” the captain had reduced his wages from $25 to $15 per month. The voyage of the Hereford had all the characteristics of an adventure novel. Tremendous storms broke upon the vessel, and the deck load of pine logs broke loose. The masts were carried away, and three sailors were crushed to pieces by a huge beam. Both legs of Skipper Jensen were broken, while the crew sustained innumerable injuries. Arthur stuck by the captain, nursing and protecting him. When the sailors tossed the dead bodies overboard, Arthur muttered a “Hail, Mary!” out of his boyhood memories from the Catholic Protectory.

“Punk.”[2]

After a week of terrible storms and suffering, the wind and sea quieted. The remains of the deck-load were cleared away, and the Hereford (now a mere hulk,) returned to an even keel. The crew were rescued by the Olivemoor, a British steamer bound for Bristol. Skipper Jensen was lowered over the side, and the crew clambered into the small boats, abandoning their derelict ship.

In Norfolk, where the crew landed, the seamen were sent to the various consuls for shipment to other ports. Arthur, however, was an American, and being at home (theoretically at least) had no consul to assist him. He was given fifty cents, and cast adrift on the streets. He appealed to Skipper Jensen, but the old man waved him away.

“Gee!” Arthur said, “d’ye t’ink dat was nice?” After me pickin’ d’ blood off of ‘is face an’ fixin’ ‘im up good all troo d’ storm.?”

Half-naked and hungry, he worked as a deckhand on a steamer for his passage to New York.

Brother Barnabas of the Protectory was glad to see him at the Broome Street branch, but the place was filled to the brim. So Arthur secured temporary employment at a club on Fifth Avenue, thought it was for a few days only.

It just so happened that W.S. Harlan, the general manager of the Jackson Lumber Company had an appeal pending in court from his conviction of conspiracy to violate the anti-peonage laws, and faced imprisonment. He came to New York with a desire to meet Irvine. The latter agreed, and suggested they meet at the club where Arthur worked (though he did not tell this to Harlan.)

When they arrived, Arthur, as a hall-boy, opened the door and ushered them in. They looked at each other in amazement.

“Is that Hans? Mr. Harlan asked.

“No,” Irvine said, “that is Buckley.”

“I think we want him for perjury!” he snapped.

“Then you know where to find him!”

As Arthur walked slowly up the wide stairway he paused, and looking back at Harlan and Irvine, a

broad grin overspread his features. He knew that Harlan would receive the fate he deserved.[3]

THE A CLUB

3 Fifth Avenue.[4]

Irvine had fallen in with a of literary people who called themselves the “A Club” who rented a building at 3 Fifth Avenue, operating a cooperative housekeeping scheme. It was a stone’s throw away from the new Socialist school, The Rand School.[5] Howard Bruebaker, the president of the “A Club” was interested in the mental and physical development of the University Settlement Clubs. “For some time,” he said, “we had considered the advisability of getting literary people together for mutual profit. Nothing definite was done until we found the house, which with its large drawing rooms, dining rooms and halls and apartments for eighteen or twenty people, being just off Washington Park.”[6]

Irvine’s new friend, the Reverend Percy S. Grant was a frequent visitor of “A Club.” It was the aim of the Socialist Party to “turn church people into voting socialists.” To that end they established the Christian Socialist Fellowship. The Christian Socialist Fellowship declared that it had two ends in view:

First: To go after the church people and make voting Socialists of them. Second: To prevent the church people being side-tracked by some near-Socialistic and near-Christian movement, which shall lead them away from real Socialism and real Christianity. The men and women at the head of this political movement are active church-workers and also active and genuine Socialists. [7]

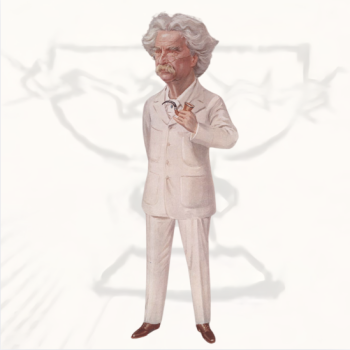

Another member of the “A Club,” Charlotte Teller, had recently published The Cage, “sociological propaganda” doubling as a “Socialist romance.”[8] The book had for the heroine a clergyman’s daughter who falls in love with an Austrian labor organizer, and finds herself torn between his ideas and those of her father. Her lover, a man unhappily married, is conflicted in his duties in a drama that culminates in the Haymarket Massacre of 1886.[9] In 1906 she brought Gorky and Tchaikowski (the leader of the Socialist Revolutionary Party) to Mark Twain for the writer’s endorsement. A friendship developed that would spur allegations of romantic involvement—much to the distress of Twain who had recently lost his wife.[10] “Driven to desperation by New York hotel, boarding house and apartment life,” said Teller, speaking of the club, “we think this will be an improvement and It seems to me a perfectly natural thing to do. We are amazed that our undertaking should be thought so extraordinary. The idea is not at all startling or peculiar, and hundreds of groups of people would be doing the same thing if they were only brave enough.”[11]

Charlotte Teller.

Then there was Platon Brounoff, a tall and broad Jewish immigrant, with masses of wavy black hair, a naïve smile, and a marked Russian accent. He was a pianist, a musical composer of Yiddish music and Jewish folk songs, popularly known as the Beethoven of East Broadway.[12]

Platon Brounoff.

There was also Soloman “Sol” Fieldman, an optician who lived at 300 West 120 Street, and paid organizer for the Socialist Party. He, per usual, kicked up some dust for the press in May 1907. He was at Printing House Square, in front of the Tribune Building, delivering a talk at a Socialist demonstration. He held a small red flag in his right hand, and a small American flag in his left. He had been arrested more than a hundred times in the past for disturbing the peace, yet never once had he been convicted. He did not fear arrest, he planned on it.

It was not long before Patrolman Francis Kiernan of the Oak Street Station, acting under orders from Commissioner Bingham, pulled Sol Fieldman out of the automobile in which he was speaking, and took him to the Tombs police court where Magistrate Crane presided.

“Inciting to riot and holding a meeting without the regular police permit” was the charge. Patrolman Kiernan said that using the red flag at such a meeting was inciting to riot and bloodshed.

“Your honor, flags are nothing,” said Fieldman, waving the red flag in one hand and the American colors in the other. “They are symbols only. The Socialists never hold a meeting without both flags. They use the flag of the country in which they are making known their doctrines and ideals, thereby to announce their intention and willingness to obey the laws of that country. They use the red flag to symbolize another and greater ideal, an international brotherhood of man. We have gone on in this city for years using this flag. The police have never interfered. I defy them to show any statute against its use.”

“Well you cannot use that flag in this city if anything I can do will stop it,” said Magistrate Crane. “I believe this policeman is right.”

“I would like to have you tell me what law there is that says I can’t wave that flag,” said Fieldman.

“The use of the red flag is substantially the same as inciting to riot,” said the magistrate. “That flag symbolizes anarchy. Its use is against the public policy of this Government. It is also, I understand, against the orders of this city’s police. You have a right to preach Socialism. I have nothing against you on that line. But to use this flag, symbol of riot and bloodshed the world over, in connection with your preaching, is a direct invitation to the men who bear you to resort to such things. I understand that this defendant is a well-known agitator, and in the hand of such, I consider the red flag a menace. I shall ask Commissioner Bingham to prohibit its it use.”

“Why, the first flag raised in this country against George III was a red flag shouted Fieldman. “It is a better flag than the American Flag!”

“The American Flag is too good to be in your hands!” said Magistrate Crane.

Lawyer J. Panken, who said he too was a Socialist, and who had seen Fieldman arrested, had come along to help him out. He discussed the ethic of Socialism for half an hour with the Magistrate.

“Fieldman,” said Panken, “by the action of the police in not interfering with the use of red flags in this city for several years, had a right to suppose there was no law against it. In Boston the other night, the police had forbidden it, and the Socialists accepting that as the law, had acceded.

“You can make this a test case if you wish,” said Magistrate Crane. “If your client refuses to promise to discontinue the use of this flag, I shall hold him and let him take the case to the Supreme Court of the United States. And that will take a long time.”

“Refuse to use the international symbol? Promise that? Never!” shouted Fieldman, dramatically waving his symbol. “Go to jail? Yes, willingly. Men have gone to jail before. I will go to jail. That is no new experience for me. But to let any policeman who take the notion say what

Is against the law and what is not—policemen who themselves care little for law unless it suits them—I will not agree. If the laws of this land, this State—and I respectfully ask your Honor to name a single statute—forbid these flags then I bow. Yes, if the courts forbid them. Yet that shall net prevent me from battling to use this flag, to change the laws to permit its use. As for inciting to riot? I have never ne done such a thing. I defy the police to quote a single sentence to show that I have done it.”

Magistrate Crane then agreed to parole Fieldman in Panken’s custody until May 27, when testimony would be taken. “I will hold Fieldman for the higher courts make a test case,” he said.

“I wonder if it’s safe to parole him? Will he return? asked the Magistrate.

“Why, your Honor, you could not keep him away from court,” assured Panken. “We differ from you in your ruling, and want nothing better than to fight this thing out. But it is by just such arrests, such ruling of these courts, that Socialists now number hundreds of thousands in this country. The half-Socialists whom we have converted are millions.”

Fieldman wanted to go right back and continue his meeting, red flag and all, but Panken said he had better not until he got a permit.

“But I shall use the red flags at my meet meetings just the same,” Fieldman replied.[13]

TRINITY CORPORATION

The momentum was kept up. Irvine had published his articles on peonage in Appleton’s Magazine, which garnered some attention. He then debated Professor William B. Guthrie (College of the City of New York) at the West Side Branch of the Y.M.C.A.

Guthrie advocated the capitalist, or competitive system, while Irvine championed Socialism and had the support of the audience. (Guthrie had to catch train, so Irvine had a chance to say a lot more things without being called on to prove them.)

Irvine discussed the question as to how New York should house its people, speaking bitterly of the tenement house owners of the city.

“If I had my way,” said Irvine, “I would burn down every one of them to the ground. I ascribe the tenement house evils, and the lack of architectural beauty, to the individualistic system, which allows every man who owns a little land to build on it any kind of a house he happens to want to build. You read every day about fences and houses. You notice every week that fine, dignified mercantile house at Broadway and Thirty-fourth Street, whose beauty is marred by a measly little building which cuts into one corner of it. There is an ecclesiastical organization here that spends more money at Albany trying to defeat legislation of reformers who are working for the betterment of the people who have to live in tenements, than it would cost that organization to fix up the tenements which it owns.” After the debate, Irvine said he referred to the Trinity Corporation. His remedy for tenement-house evils, was the ownership of them by the city.

“I do not approve of existing conditions,” Guthrie responded, “but in making changes I ask for conservatism. These evils are always exaggerated. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which helped to precipitate the Civil War, matched the truth in very few places, and Simon Legree is almost a caricature. The radical agitators from 1850 to 1860 brought on the Civil War, which but for them might have been averted. I believe that existing conditions in tenement houses ought to be improved, and will be, but I scoff at the idea of allowing a board at the City Hall to manage our homes for us. Picture the graft conditions as they now are, and ask yourself: ‘What would likely be the limit if a hundred times more power were given to the City Government?’ The world has moved forward wonderfully, and it has done so under the competitive system, which drops a bad machine and takes up a good one. It shouldn’t be abolished on short notice. There has always been classes in society, and there always will be. I am not ready to advocate the taking away from a man of his right to own his own home.”

Irvine scoffed at the idea of the ordinary man in New York owning his own home, and most of the audience joined him.

“I can prove that there is room in New York City for every head of a family to have his own cottage,” said a man in the audience. “Do you want me to prove it?”

“I guess not,” said Guthrie. “I’ve got to catch a train.” [14]

PEOPLE OF THE UNDERWORLD

I. INTERCOLLEGIATE SOCIALIST SOCIETY.

II. THE CRY OF PEONAGE.

III. MUCKERS.

IV. GALLAGHER’S HELL.

V. PUNK.

VI. SOUDAN.

VII. BOWERY.

VIII. “IT IS A BETTER FLAG THAN THE AMERICAN FLAG.”

IX. PENETRATING THE ASCENSION.

X. “THE UNIVERSE IS BASED ON THE SUBJECTION OF WOMAN.”

XI. PROGRESSIVE WOMAN SUFFRAGE UNION.

XII. THE CHRISTIAN SOCIALIST FELLOWSHIP.

XIII. THE ERUPTION OF THE END.

SOURCES:

[1] “Three of Crew Were Lost.” The Chattanooga Daily Times. (Chattanooga, Tennessee) April 9, 1907; “Story of the Wreck of Norwegian Bark Hereford.” The Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) April 16, 1907.

[2] My Life In Peonage Pt. III: The Kidnapping Of ‘Punk.’” Appleton’s Magazine. Vol. X, No. 2. (August 1907): 190-197.

[3] My Life In Peonage Pt. III: The Kidnapping Of ‘Punk.’” Appleton’s Magazine. Vol. X, No. 2. (August 1907): 190-197.

[4] Trowbridge, Edwin. “New Shop Fronts.” The Brickbuilder. Vol. XVI, No. 8 (August 1907): 136-140.

[5] “The Rand School.” The Evening Standard. (London, England) January 9, 1907.

[6] “The A Club’s Object.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) February 11, 1906.

[7] “Constitution of the Christian Socialist Fellowship.” The Christian Socialist. Vol. V, No. 13 (July 1, 1908): 5.

[8] “Review: The Cage.” The Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.) March 2, 1907.

[9] “Advertisement: The Cage.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) March 8, 1907.

[10] Twain, Mark; Paine, Albert Bigelow. Mark Twain’s Letters: Volume II. Harper & Brothers. New York, New York. (1917): 794-795; Margarita, Marinova D. Transnational Russian-American Travel Writing. Routledge. New York, New York. (2012): 60-61; Twain, Mark. Autobiography of Mark Twain: Volume II. University Of California Press. Berkeley, California. (2013): 564.

[11] “The A Club’s Object.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) February 11, 1906.

[12] “Scoffer Among Socialists” The Sun. (New York, New York) November 16, 1908; “Platon Brounoff: Conductor, Arranger, and Composer of Yiddish Music 1859-1924.” Jewish Research Music Centre, February 10, 2020. https://www.jewish-music.huji.ac.il/content/platon-brounoff.

[13] “Does The Red Flag Go, Or Not?” The Sun. (New York, New York) May 22, 1907; “Socialist Has Heated Argument With Magistrate Crane.” The Tribune. (New York, New York) May 22, 1907; “The Red Flag A Sign Of Disorder.” The Square Deal. Vol. II, No. 12 (July 1907): 12.

[14] “Denounces Tenement Evils.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) June 10, 1907; “Talk Of Tenements.” The New York Tribune (New York, New York) June 10, 1907.