THE LOST CANON OF PROPORTIONS OF THE EGYPTIANS

September 7, 1875.

Judge and Castle once again called on Blavatsky.[1]

“Thanks for the scarabaeus,” she said to Judge, greeting him with much effusion.[2]

Judge pretended ignorance.

“It is useless to pretend,” said Blavatsky, informing him how he had sent it, and where the clerk had posted it.

Blavatsky then turned to Castle, her eyes flashing fire. “Perhaps you think, Mr. Castle, that my spirit was not with you and that I did not hear your scornful and contemptuous remarks about that pistol, but I was there and I heard every word and knew every thought that you were thinking.”

Castle was completely surprised, and hardly knew what to say. He tried to tell Blavatsky that she was mistaken about any contemptuous or scornful remarks, but she would not be appeased. During the long evening that followed, Castle would have uncomfortable sense of Blavatsky’s occasional wrathful glance.

There was an interesting company of about seventeen people present that evening, and the discussion that ensued was very much the same as on the former occasion, except it entered deeper into the mysteries.

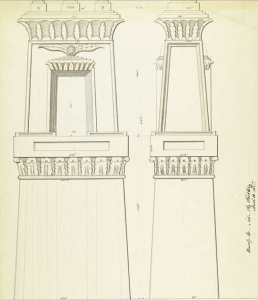

Henry Stevens, a member of the editorial staff of The New York Observer, had told Olcott and Blavatsky of a new acquaintance of his, a man named George Henry Felt, who was a math teacher and student of sacred geometry.[3] Very much desiring to hear of his research, Felt was asked to speak that evening on “The Lost Canon Of Proportion Of The Egyptians.” It was somewhat apropos with the Brooklyn Bridge approaching completion. John Roebling originally designed the towers of his bridge to resemble Egyptian pylons.[4]

Among those present were Charles Sotheran, and Olcott’s old colleague from The Daily Graphic, W.L. Alden. Joining them was Henry J. Newton, President of the First Society of Spiritualists, and an amateur photographer of considerable repute. He had recently conducted experiments involving spirit-photography in the home of the Medium, Dr. Ruggles, at 492 State Street, Brooklyn.[5] There was D.E. de Lara, an old Sephardic-Portuguese gentleman, for whom Blavatsky and Olcott had great affection. Emma Harding Britten, a Spiritualist since the beginning, was there with her husband, William Britten. There was John Storer Cobb, an English barrister, leading figure in the Cremation Movement, and former editor of a magazine for reformed Jews called New Era. Rounding out the rest, there was Dr. Seth Pancoast, Blavatsky’s physician in Philadelphia who practiced Alchemy, Charles E. Simmons, a well-known New York physician, Herbert D. Monachesi, a brilliant young Italian-American journalist with “very psychical temperament,” and Charles Carlton Massey, an English barrister keenly interested in Spiritualism. Prompted by People From The Other World, he went to America in 1875 to investigate the phenomena himself.[6]

Roebling’s 1857 drawing of Brooklyn Bridge Egyptian design.[7]

When Felt’s lecture began, he proved remarkably clever draughtsman. He had prepared a number of beautiful drawings with which to illustrate his theory that the canon of architectural proportion employed by the Egyptians, as well as by the great architects of Greece, was preserved in the temple hieroglyphics of the of Egypt. “By following certain definite clues,” said Felt, one could inscribe what he called the “Star of Perfection” upon a certain temple wall, within which the whole secret of the geometrical problem of proportion would be read. The hieroglyphs outside the inscribed figure were simply “blinds to deceive the profane curiosity-seeker.”

Felt said that while making his Egyptological studies, he had discovered that the old Egyptian priests were magical adepts, possessed the ability to evoke and employ the spirits of the elements. These priest-magicians, had left their formularies on a record which he had deciphered. Felt then made the claim that he had put them to the test, and had actually succeeded in evoking the elementary spirits.

“Could you practically prove this perfect knowledge of the occult powers possessed by the true ancient magician?” asked Dr. Pancoast, an accomplished Kabbalist. “The evocation of spirits from the spatial deep, for example.”

“The communion of mortals with the dead, and the reciprocal intervention of each in the affairs of the other, is not a mere conjecture among the ancient Egyptians, but reduced to a positive science,” said Felt. “They produced the phenomena of so-called materialization by a combustion of aromatic gum and herbs, instead of a séance of persons to draw the necessary power from. I have produced these phenomena in that way and can do it again.[8] I have been able to cause the materialization of human forms in full daylight, by magical appliance. I can replicate the experiment with my chemical circle. I could call into sight hundreds of shadowy forms resembling a human, but I have seen no signs of intelligence in these apparitions.”

“One who studious and became absolutely possessed of the spirit of inquiry and of truth might, at a moment’s notice and by the mere force of a wish and desire, be transported to India, or China, or any other point, and that such a person might hold free communion with spirits or with spiritual things,” said Blavatsky.

“I am willing to aid some persons of the right sort to test the system for themselves,” said Felt, “and will exhibit the nature spirits to you all in the course of a series of lectures, provided that I am compensated.”

After Felt’s discourse, an animated discussion ensued. Olcott rose during a convenient pause in the conversation, briefly sketched the present conditions of the Spiritualist Movement, and the attitude of its antagonists, the materialists. He meandered on the irrepressible conflict between science, and religious sectarianism; and on the philosophical character of the ancient theosophies, and their ability to reconcile all such antagonisms.[9]

It was sometime after midnight when Blavatsky suddenly exclaimed, “But why need we only meet and talk; why not materialize; why not, at the present moment, form a society and undertake the study of truth in connection with this great and absorbing subject?”

The others agreed, and it was also understood and agreed specifically that those who joined the new Society should allow nothing else to interfere, nor step between them and the pursuit of this great subject.

While Castle was very desirous of knowing more about the topic, he felt that he had no right to throw aside everything else, and therefore could not join. When those gathered around the table, at Blavatsky’s command, joined hands and arose to repeat the promise, one to another, and to form the Society, Castle withdrew and kept to his seat.

Blavatsky, at the other end of the room, leaned toward him with her eyes emitting an angry light. She motioned for Castle to stand up and join hands, but he shook his head.

As soon as these preliminaries were over, and the company began to disperse and converse with one another, Blavatsky came quickly to where Castle was standing.

“Perhaps, Mr. Castle, you do not think that I fully understand and appreciate what it is that comes between your spirit and mine that prevents you yielding to me, but I do,” said Blavatsky in an expressive voice. “There is another person who stands between you and me, but I will gain that influence yet.” After a few more remarks, Castle and Judge withdrew.

“You seem to have aroused Madame’s ire,” said Judge.

“A fact that I regret,” Castle replied.[10]

Another meeting was held the following day at 46 Irving Place. It was then when the minute book for the new Society began. Upon the motion of Judge, it was voted that Olcott should take the chair, and upon motion, Judge act as Secretary. A committee of four was appointed to draft a constitution and by-laws. Another meeting was held on September 13, with Olcott once again in the chair, while Sotheran acted as Secretary. It was resolved that the name of the new group would be called The Theosophical Society.[11]

SOURCES:

[1] Ransom, Josephine. A Short History Of The Theosophical Society. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, India. (1938): 78.

[2] Judge writes: “When I called on her at the end of the week the second time, she greeted me with thanks for the scarabaeus. I pretended ignorance. But she said it was useless to pretend, and then informed me how I had sent it, and where the clerk had posted it. During the time that elapsed between my seeing her and the sending of the package no one had heard from me a word about the matter.” [Sinnett, Alfred Percy. Incidents In The Life Of Madame Blavatsky. G. Redway. London, England. (1886): 186-199.]

[3] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 32. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) H.M. Stevens. (12/1/1875); “Origins Of Theosophy.” Hanford Semi-Weekly Journal. (Hanford, California), January 7, 1896.

[4] Shapiro, Mary J. A Picture History Of The Brooklyn Bridge. Dover Publications, Inc. New York, New York. (2013): 20.

[5] [Quaestor Vitae “The Real Origins Of The Theosophical Society: Pt. I.” Light. Vol. XV, No. 776 (November 23, 1895): 569-570; Quaestor Vitae “The Real Origins Of The Theosophical Society: Pt. II.” Light. Vol. XV, No. 777 (November 30, 1895): 577.] Dr. Ruggles was incidentally Blavatsky’s former landlord; his wife, Emily Ruggles (or so she claimed,) was the first to bestow the title of “Madame” upon Blavatsky. Emily Ruggles was a “motherly” woman who earned a reputation of being “the guardian angel of the mediums.” Over the years 492 State Street had sheltered such noted names of the Spiritualist movement as Margaret Fox-Kane, Victoria, and “Tennie” Claflin, Diss Debar, and Madame Blavatsky. In an 1893 interview with the New York World, Ruggles states: “Blavatsky] is one of the many mediums that have sought shelter here. Mme. Blavatsky spent about four months with me during the time she was a medium and before she conceived the idea of springing Theosophy. She was a jolly, good-natured woman, an unscrupulous trickster, and I know if she were alive now, she would be the first to appreciate the funny side of the adulation which she receives from the Theosophists. She was a good medium, but gave it up for something out of which she could make more money. She was a remarkably brainy woman, spoke seven languages and was entirely free from religious scruples. I used to call her my Russian bear, because she ate so much…She was passionately devoted to her cigarettes. Between two cups of coffee at breakfast she would have to smoke a cigarette, the stub of which she never failed to lay on my damask table-cloth to burn a hole therein. When I chided her for her carelessness, she would laugh a merry laugh and say: ‘I will give you all the purgatory you want on earth.’ She referred to the Spiritualist’s belief in purgatory, which is similar to the Roman Catholic Church…Blavatsky was married to a Russian dignitary when she was sixteen. Two months later she broke a chandelier over her husband’s head and came to America. When she first came to me, she was simply Helen Blavatsky. It was I who gave her the title ‘Madame,’ which always stuck to her. I thought she was too remarkable to be anything less dignified than Madame.” [“Their Sheltering Arms.” The World. (New York , New York) April 2, 1893.] We are told that Blavatsky was referred to as “Madame” by J.M. Peebles when she was in Cairo, Egypt, in the early-1870s. [“Round The World Among Spiritualists.” The Spiritualist Newspaper. Vol. VI, No. 6. (February 5, 1875): 61-77; Peebles, J.M. Round The World; Or Travels In Polynesia, China, India, Arabia, Egypt, Syria, And Other “Heathen” Countries. Colby And Rich, Publishers. Boston, Massachusetts. (1875): 315.] If we take Ruggles’ statements to be correct, this may add validity to Blavatsky’s own claims to being in America sometime in early 1850s.

[6] “Our New Departure.” The New York Echo. (New York, New York) April 30, 1878; Ransom, Josephine. A Short History Of The Theosophical Society. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, India. (1938): 78, 110-115.

[7] Shapiro, Brooklyn Bridge, (2013): 20.

[8] “Origins Of Theosophy.” Hanford Semi-Weekly Journal. (Hanford, California), January 7, 1896.

[9] Britten, Emma Hardinge. Nineteenth Century Miracles. Lovell & Co. New York, New York. (1884): 296.

[10] C. “Days With Mme. Blavatsky” Hawaiian Gazette. (Honolulu, Hawaii) October 19, 1894.

[11] Judge, William Q. “Historic Theosophical Leaves.” The Path. Vol. IX, No. 1 (April 1894): 1-3.