A look at the October 4, 1900, edition of The New York Tribune might provide some insight into Ernest’s motivation for returning to America:

Winston Spencer Churchill. Who has just been elected a member of Parliament, is to make a three months’ lecture tour in America. He opens in the ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria on December 12, the anniversary of the capture by the Boers. Mr. Churchill’s subject will be “London to Pretoria, via Ladysmith,” with the story of his capture.[1]

Churchill’s second lecture would be in the ballroom of the Waldorf Hotel, where Ernest and Aimée were living. With the British government actively searching for him, Ernest could ill-afford placidity regarding his fate. He was suspected on the Dunnottar Castle, he would be suspected in New York; the best course of action would therefore be an offensive. Ernest would garner public sympathy towards himself and the Boers, while simultaneously dampening American support for the celebrated, though controversial, Churchill. One gets the impression, when comparing the tour stops of both Ernest and Churchill, that Ernest was visiting these hubs just before Churchill made his appearance.

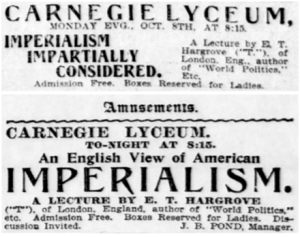

Advertisement’s for Ernest’s lectures at the Carnegie Lyceum, October 8 & 12, 1900.[2]

Back in March, while still in South Africa, Churchill received a letter from Major J.B. Pond, the same lecture agent who organized the American leg of Mark Twain’s come-back tour, whom Twain regarded as “neither truthful nor sensible.” Churchill, after returning to London the previous summer, exchanged letters with Pond, scheduling the dates, duration, and materials, for a lecture tour. “The War As I Saw It,” the title of Churchill’s lecture, would be a narrative of his experience in Boer captivity, his escape, the relief of Ladysmith, and his entry into Pretoria. With the knowledge that a lecture tour takes a certain amount of time to plan, and organize, Ernest’s subsequent actions would appear planned and coordinated well-before returning to New York.[3]

Major Pond, it would seem, was cornering the market on lecturers on the Boer war, both for and against, with the two Harrow boys. From mid-October until mid-February, Ernest would tour the mid-Atlantic and New England with two talks, “Imperialism Impartially Considered,” and later, “The White Man’s Burden.” Both these talks would address the Boer War and the recent “Boxer Rebellion” which saw “China’s frenzied outburst of hatred for all foreigners has resulted in a massacre unique in the history of civilization.”[4] Ernest and Pond quickly went to work, organizing an interview with the New York Tribune at the Waldorf-Astoria on October 6th.

We have had it dinned into us for some time past that the white man has a burden. It is said to be the burden of duty,” Ernest said. “The trouble is that that part of his burden which the white man seems the most loath to bear is the elementary duty of minding his own business in his own country. The English speaking peoples are oscillating between the two extremes of selfish isolation and universal grab, the one as bad as the other. There must be a middle path, and in my lecture I shall endeavor to suggest what that is. Years ago American thought was largely influenced by thought in England,” said Ernest. “Now the tide has turned and flows from west to east. At the present time England is more influenced by America than America by England. So thus one object of my visit is to influence English thought by and through America—paradoxical as that may seem.”[5]

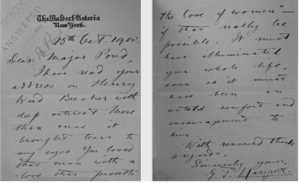

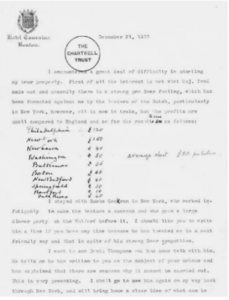

Letter from Hargrove to Pond.[6]

Ernest kicked off his lecture series at the Carnegie Lyceum on October 8, 1900, with a talk titled, “Imperialism.”[7] A week later, on the evening of October 12, after an introduction from Major Pond, Ernest spoke to an audience of around 50 people.[8] In his speech, The English View of America,” Ernest characterized imperialism as a “policy of universal grab.” “Anti-imperialism, on the other hand,” said Ernest, was a “a policy of selfish isolation.” Though it was only attended by a small number of people, they “vigorously applauded the speaker’s anti-imperialistic sentiments.”[9] Three days later Ernest writes a letter to Pond:

Dear Major Pond, I have read your address on Henry Ward Beecher with deep interest.[10] More than once it brought tears to my eyes. You loved that man with a “love that passeth the love of women”—if that really be possible.[11] It must have illuminated your whole life, even as it must have been an untold comfort and encouragement to him.[12]

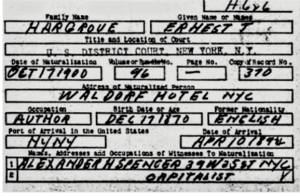

If B. Fletcher Robinson is to be believed, Ernest declared his intention of seeking American citizenship while in Cape Town, however, the looming threat of imprisonment for treason by the British authorities, likely hastened this desire. On October 17, Ernest, together with A.H. Spencer, now the Vice President of the (New York) Theosophical Society, filed his naturalization papers at the New York District Court.[13]

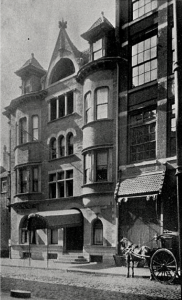

Main Entrance and Lobby of The Waldorf.

The “Red Room” and “Turkish Salon” (bottom) inside The Waldorf.

Naturalization.[14]

It was learned in October that Paul Kruger, of the now fallen Transvaal republic, secretly left South Africa on a Dutch cruiser, Gelderland.[15] Ernest subsequently sent a telegram to the South African News, stating that his dealings with President Kruger had contributed greatly to the credit of the Afrikander cause, and announced that he would return to South Africa to face the charges leveled against him.[16] Ernest would have felt the accusation of treason to be a stain upon his honor—had these charges any basis in truth. Ernest, however, claimed “to be a good Britisher in working for this end,” and therefore had no intention of returning to South Africa only to be tried in a kangaroo court.[17]

Aimée, meanwhile, likely would have paid a visit to her brother Fred, whom she had not seen since she married Ernest. Fred, now a doctor, had married Aimée’s maid-of-honor, Gertrude Annis, in November, 1899. They were now living in Browne Park Village, Long Island.[18] Emil and Minnie had moved to Point Loma to be closer to Tingley, and in the interest of raising capital for Point Loma, Emil entered the mining business.[19] Minnie, more and more suspicious of Tingley, refused to join the Universal Brotherhood with her husband. Rumors circulated that Tingley was preventing Minnie from speaking with Emil, and forced her to live alone, in a small tent on the outer grounds of the compound.[20] Emil, who was regarded as one of the “three fathers of Theosophy” at Point Loma, had instructed the community to detain Minnie if she ever asked to be taken into San Diego, on any pretext, “as she was somewhat unbalanced in the mind.” (How much, if any of this, Aimée was made aware, is unknown, however, would all be published in the newspapers within a two years.) As Emil was entering the mining industry, Clem’s venture into that business was ending, as his enterprise at the “Accidental Mines,” lived up to its name when it was destroyed by fire in September 1900.[21]

Ernest was, in Aimée’s words, “very morose at that time,” and said that to Ernest “used to go into his room and stay for hours at a time. He was what the Theosophists call meditating.” Ernest had not forgotten Judge’s instructions: “You will have to “give up something” […] Don’t fail me in this […] you are not to make all those preparations so often indulged in by people. If by any god’s chance you should flittingly or otherwise see me, please calmly note all appearances and let me know all about it.”[22] (Cavé’s “Fragment,” in the December, 1900, issue of The Forum, would, incidentally, be a reflection on meditation.)[23] Though Ernest would contribute an occasional (anonymous) article to The Forum, he largely remained distant from the Theosophists while in New York. He only needed to read the New York Tribune, however, to know of his friend’s well-being. The Griscom steamer, St. Paul, was recently involved in an accident at sea, and entered New York harbor with a missing propeller. The article also reported that Clem was still sick, and bed-ridden in his home at Flushing.[24]

The Osburn House, Rochester New York, c. 1899.[25]

On November 7, 1900, Ernest, was at the Osburn House, in Rochester, New York. His plan was to circulate a petition, and gather American signatures, which he hoped would have some effect in inducing Great Britain “to try to bring about a settlement short of destruction of the Dutch pride in South Africa.” To make his mission a success, he planned to influence some leading American statesman to appeal to the British public.[26] The purpose of Ernest’s Rochester visit was to meet W. Martin Jones, the Rochester lawyer whose works on international arbitration appealed to him back at The Hague. Ernest told an interviewer: “They say that a prophet is usually without honor in his own country, but I am glad to find that is not the case with Mr. Jones.” When asked of his opinion on international arbitration, Ernest replied:

I have always hoped that America would take a leading part in this next international development […] The United States stands as a permanent example of what co-operation can accomplish between states, and, although I do not for one moment suggest or wish that the nations of Europe should co-operate to the same extent as is possible in this country, it is to be hoped that, while retaining their complete independence, they will nevertheless learn that their interests are fundamentally identical, and that the interdependence of the nations is as great a truth, and should be as widely recognized as such, as the right of a people to freedom and autonomy.[27]

Lobby of the Hotel Touraine c. 1899.[28]

He then went to Boston, where he stayed at the Hotel Touraine.[29] Perhaps there was a mystical connection, as the Hotel Touraine was built on the site of the former Hotel Boylston, where, during the 1891 Theosophical Convention the appearance of W.Q. Judge changed right before the eyes of the audience.[30] On November 28, 1900, Ernest gave a lengthy interview to a reporter from The Boston Globe. He predicted that within two years there would be a great revolution of feeling in England, which would “hurl Chamberlain from Power.” “The war had created the Afrikander nation” said Ernest, “which was as real as the American nation.”[31] The Hotel Touraine was just a stone’s throw away from the Tremont Theatre. Nearly four years had passed since the launch of the Crusade, when he told the audience:

A nation, in addition to ordinary conceptions of selfishness and unselfishness, has a pride which is not true patriotism; and what Theosophists have to do is try and rise to a higher ideal of true patriotism, which is this: the idea that there is something greater in this world besides conquest; that it is nobler to help humanity then to crush it beneath your heel, and instead of carrying war and bloodshed from nation to nation, carry to nations all over the world a message of hope; and there is not country on the face of the globe which can afford to send such a message as that like America.[32]

On December 3, 1900, Ernest met with Commandant W.D. Snyman, of General De Wett’s staff. He was one of five Boer refugees who arrived in New York a week earlier. The British had dispossessed Snyman’s farm, and all of his livestock; his wife, and all his children, (except a son who was among the five refugees,) were in the hands of the British, and he was working on bringing them to America.[33] The meeting between Ernest and Snyman was, presumably, in connection with the creation of the new Transvaal League of New York, as both men were principle speakers at engagement, two weeks later, under the auspices of the League.[34] On December 4, “most convincing” lecture, titled “With Briton And Boer In South Africa,” was delivered at M.I.T.’s Technology Club (71 Newbury Street,) in the shadow of the high-gothic steeple of the Church of the Covenant.[35] On December 5, Ernest gave his talk, “The White Man’s Burden,” at the Twentieth Century Club at 2 Ashburton Place. The rooms were filled, and many of his remarks were greeted with loud applause. He said in part:

The English newspapers hardly mention the fact that there are 4,700 tenements of one room each, with an average of 11 persons in each, but print column after column or the duty of England in civilizing South Africa and her duty in China. We get it into our heads that we ought to conquer other nations in order to civilize them, but we forget what many of them could do to civilize us. There has been civilization in the past that exceeded ours, and it is absurd to set up any standard of civilization for all nations to follow. We want to carry Christianity into foreign countries, and we think that wherever the flag goes there will go the Bible and Christianity; but you do not make Christians of them as far as I can see.[36]

The Common Room of the Technology Club.[37]

Churchill, meanwhile, had arrived in New York on December 8, 1900. On the afternoon of his arrival, Major Pond held a press conference for reporters at his office at the Everett House. Mark Twain showed up to ask the questions. ”I have now told the real story in London,” Churchill said, “but I think it will be new over here. I intend to relate It m my lecture at the Waldorf.” Twain asked, “It has been related that a Dutch maiden fell in love with you and assisted you to flee. You have said that it was the hand of Providence. Which is true?” Churchill answered, “It is sometimes the same thing.”[38]

“Studio House Of Mrs. Ole’ Bull.”[39]

The following day (December 9, 1900,) Ernest was in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he was a special lecturer as part of the Cambridge Conference series in the Studio House of Sara Bull at 168 Brattle Street.[40] It was the hub of Cambridge’s intelligentsia and artistic community, where Dharmapala, and Vivekananda spoke, and where Harvard’s leading philosophers, like William James, George Santayana, and Josiah Royce made regular appearances.[41]

“Harvard Square Looking West,” c. 1900. (The Cambridge Room)

Ernest was, in Aimée’s words, “morose,” and Colonel Olcott’s comments regarding Ernest’s activity in South Africa in the most recent issue of The Theosophist certainly did not boost his morale:—“This is a sad downfall for a young man who was formerly so much esteemed among us, and we sympathize, warmly, with the honorable family into which he married a short time ago.”[42] Perhaps the reception of Ernest’s talk that day brought him some cheer. “International Relations and the Boer War,” was warmly received, one audience member wrote:

[Ernest spoke] in a style which quite established his fame as lecturer, in this city at least. His knowledge of the subject upon which he spoke is absolute and accurate […] the lecture was comprehensive and included a brief survey of the existing conditions, their cause and effects. Many points before, before obscure in the minds of the audience, were made clear during the course of the lecture, and those present departed with the feeling that they at least were in a position to understand and study knowingly the course of the war.[43]

Churchill’s first lecture before a large audience in Philadelphia on December 11, 1900. The crowd gave a generous round of applause at the close of his talk, but Churchill was surprised to discover the pro-Boer sympathies of some of the audience. The next evening Churchill lectured at the Waldorf. Major Pond invited Twain to present Churchill. Twain, a fierce anti-imperialist, and concerned with America’s own burgeoning empire, offered a counterweight to both Churchill and Ernest (who was very likely at the event.) Ernest, an Englishman who became an America, and supported the Boers; Churchill, half-American half-British by birth, supported the British; and Twain, the American, who supported neither Boer nor Brit, rather, his sympathy lied with the native African peoples. “I think that England sinned when she got herself into a war in South Africa which she could have avoided,” Twain said, “just as we have sinned in getting into a similar war in the Philippines.” Twain’s introduction for Churchill displayed his characteristic wit:

Mr. Churchill by his father is an Englishman, by his mother he is an American, no doubt a blend that makes the perfect man. England and America; we are kin. And now that we are also kin in sin, there is nothing more to be desired. The harmony is perfect, like Mr. Churchill himself, whom I now have the honor to present to you.[44]

The New York Tribune described the rest of the talk, which included the following excerpt:

The escape was made just a year ago last night, and not far from the hour at which he was speaking. It was easy enough to get out of the State Model School, where the prisoners were confined, but it was harder to get over the iron fence. He accomplished this in a spot of deep shadow, but almost failed through his clothing catching on a point of the decoration at the top of the fence, a place, as he told [Twain] in a loud aside, where decoration did absolutely no good. He was saved by the fact that the sentry took just that moment to light his pipe, and allowed him time to free himself unseen…He found the railway and stowed himself away on a train, which, happily, proved to be going east, instead of in any other direction, which would have been useless. He hid himself under empty coal sacks, and, “as the newspapers would say, ‘passed a restless night.'” He finally got off the train without detection and into a wood, where he saw a vulture. The vulture had nothing to do with the story, but Mr. Churchill seemed fond of him, as his existence had been disputed by persons who pretended to know a good deal about South Africa, and Mr. Churchill seems inclined to bring him into the story for the express purpose of insisting that he saw him.[45]

Churchill would later write:

My opening lecture in New York was under the auspices of no less a personage than “Mark Twain” himself. I was thrilled by this famous companion of my youth. He was now very old and snow-white, and combined with a noble air a most delightful style of conversation. Of course we argued about the war. After some interchanges I found myself beaten back to the citadel “My country right or wrong.” “Ah,” said the old gentleman, “When the poor country is fighting for its life, I agree. But this was not your case.” I think, however, I did not displease him; for he was good enough at my request to sign every one of the thirty volumes of his works for my benefit; and in the first volume he inscribed the following maxim intended, I daresay, to convey a gentle admonition: “To do good is noble; to teach others to do good is nobler, and no trouble.”[46]

Ernest, who read Churchill’s works, would admit: “Winston Churchill [is]…often brilliantly right, he is as often glaringly wrong, both practically and ethically. But he writes as few can, with perfect clarity, with humor, in a style ideally adapted to his subject.”[47]

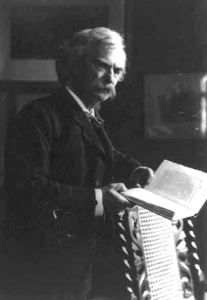

Mark Twain c. 1900.

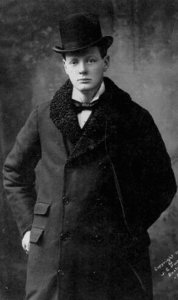

Winston Churchill c. 1900.

James Pond

The Grand Ballroom, The Waldorf Hotel.[48]

Churchill and Pond arrived in Boston on 16 December and checked into the Hotel Touraine. That day Pond brought Winston Churchill, the American novelist, to the hotel to meet the British Winston Churchill. The meeting of the two Winston Churchills received a great deal of press attention, which can be attributed to Pond’s taking advantage of every promotional opportunity.[49]

Sherry’s Restaurant.[50]

On December 19, 1900, Ernest was the principle speaker at an event hosted by the newly-formed Transvaal League of New York. In his well-attended talk at Sherry’s Restaurant. Ernest began his talk, “How Americans Can Help The Boers,” by declaring that “he was not ashamed as an Englishman to declare his sympathy for the Boers,” and began by citing Burke and Pitt and other English politicians who stood by the American colonists in the War for Independence, and both of whom made pleas for help for the Boers in way of sympathy openly expressed by people of the country. Ernest first told some reasons why he thought Americans should help the Boers, and then advanced his plan as to the way in which they might help them, which in brief is by a petition to the British people to stop the war.[51] The proposal was to circulate signatures for the following petition or protest:

We the undersigned, citizens of the United States, protest against the continued slaughter and threatened extinction of the citizens of the South African Republic and the Orange Free State, and we urge the people of Great Britain and Ireland and the British Colonies to refuse to countenance a proceeding which they can bring to them neither gain nor glory.

The protest as first presented had the additional words—“but only dishonor”—but upon suggestion, it was voted to strike them off.[52] Ernest then said, in part:

Why should Americans help the struggling Boers? I fail to see how America can gain anything by seeing these two republics crushed out or existence. They are fighting for freedom. It is the same fight that you fought 100 years ago. If you cannot help them by force of arms, help them at least by your sympathy…You can’t affect this Chamberlain Government by a hair’s breadth. It can be done only through the American citizen protesting to the English voter, who, in turn, will see that his representative in Parliament will act, or else his seat will be in jeopardy. We are not bothering about Chamberlain, for so soon as the English people get sick of him, they will depose him…In my opinion, the thing to do is for the American people to sign a formal protest, not to the Queen, not to the Government, but to the English people.[53]

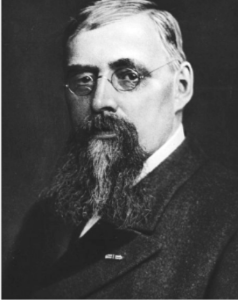

Ernest was so striking a likeness of Joseph Chamberlain, that few could fail to notice the fact. He had the appearance of a “pale ascetic” with a “strikingly intellectual countenance.” Instead of Chamberlain’s monocle, however, Ernest wore ordinary double eye glasses. His manner was quiet, and his unobtrusive delivery was impressive “not by any oratorical traits but by a reserved force of deep feeling and moral earnestness.”[54] Ernest closed his talk by reminding the audience that he spoke as an Englishman, and assured the meeting that if an Englishman saw a page of the London Times devoted to this protest, and saw signatures of Americans every day for a week, he would begin to think that there was something in it. Snyman, who shared the platform with Ernest, added: “I can assure you that Great Britain does not know what she is going to get in the end of this thing.” Ernest and the Transvaal League were proving effective in their efforts. As one paper stated, “Mr. Hargrove is a versatile, eccentric and altogether amusing personage, who has met with great success in the capacity of his own press agent.[55]

Later that evening Snyman went to the Sturtevant House to join the nearly one hundred members of the Irish Nationalist Society for a banquet given in honor of Major John McBride, commander of the Irish Brigade in the Transvaal. It is not clear if Ernest accompanied him, but given the context, it would seem likely. McBride, who would marry Maud Gonne in 1903, was met with a lengthy burst of cheers when he rose to speak.[56] McBride stated:

I’ve seen English soldiers run like deer from forces not one-fifteenth their number on a score of fields. The British Army is rotten throughout. All its officers are incompetent, and almost all the Irish portions are disaffected. There is now on foot in Ireland a movement against enlistment in the British Army, and I can’t urge too strongly the necessity of uniting against England..[57]

Two days later (December 21, 1900) Churchill wrote a letter to his mother from the Hotel Touraine which stated:

I encountered a great deal of difficulty in starting my tour properly. First of all the interest is not what Maj. Pond made out and secondly there is a strong pro-Boer feeling, which has been fomented against me by the leaders of the Dutch, particularly in New York…I get on very well with my audiences over here, although on several occasions I have I have had almost one-half of them strongly pro-Boer, and of course I do not have the great crowds that always come in England.[58]

Churchill’s Letter & Tremont Street c. 1900.[59]

In late-December Aimée and Ernest were guests of Dr. George McClellan and his wife Harriet, at their residence, on the corner of Broad and Spruce Streets in Philadelphia. McClellan the grandson of the founder of the Jefferson Medical College, also named George McClellan, and himself the founder of The Pennsylvania School of Anatomy and Surgery, where he taught anatomy and surgery. His work, Regional Anatomy In Its Relation To Medicine And Surgery, in which McClellan published his own photographs and illustrations from his own dissections, was widely known.[60] On December 30, 1900, in the drawing room of Philadelphia’s New Century Club, Ernest delivered a talk titled “The Moral Progress of the Nineteenth Century,” for the Society of Ethical Culture. Ernest’s discourse was centered on the application of the ethics of Christ to international conduct. But Ernest did not fail to urge, very strongly, that the moral obligation of the individual man, who wished to aid a sister nation, should begin by having the “right spirit in his own home.” The moral advance in society, Ernest said, repeats itself, but not with absolute sameness. History, broadly viewed, moved in a spiral circle—traversing again and again, “but always on a little higher level.” In his talk Ernest stated:

We find some of the most inexcusable wars in history being waged at present. The South African and the Chinese wars are barbarisms of the worst sort because they are being waged by people who should know better. If we are to recount the horrors of those conflicts, then you might say pirate no more about, progress. I think, however, that the emphatic protest of the people on ethical grounds against these warlike tendencies shows that progress has been made.

New Century Club, 124 South Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania c. 1899.[61]

“It is a pity that the fine lecture…could not have been delivered as a Christmas sermon before an overflowing congregation in one of our large Philadelphia churches,” remarked one editorial.[62] Ernest worked with Charles D. Pierce (Consul General of the Orange Free State,) under the auspices of the Transvaal League to produce a booklet titled, An American View Of The South African Situation.[63] On New Year’s Day The New York Tribune printed a headline which caught his attention: “United Australasia Rejoices.” The article described the festivities of newly Federated Australia: “When midnight struck, bells pealed, and cannons boomed a welcome to the birthday of United Australasia.”[64] The news of United Australia gave Ernest an idea. Pending Leyd’s approval, he would re-work the book for An American View for Australian audience, then travel to Australia to spread the information and continue gathering petitions. This would fit with Leyd’s all-encompassing plan.

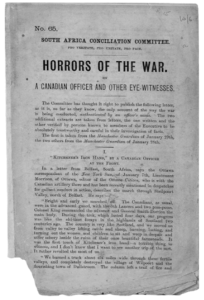

The New York Sun, of January 7, 1901, told its readers that Dr. Leyd’s, as diplomatic agent of Transvaal, was recruiting men from Holland, Belgium, France, and Germany to farmstead Namaqualand, ostensibly as colonists. It was suspected, of course, by the British, that the true reason was Boer reinforcements.[65] The Sun held a strongly anti-British stance at this time. On the day of the Leyd’s article, The Sun’s unnamed “Ottawa correspondent” sent a letter which described “the punitive measures taken against the Boers” published in the January 2, 1901, issue of The Ottawa Citizen to the Manchester Guardian, to be used for propaganda against Great Britain.[66] The author of the letter was Lieutenant E.W.B. Morrison, editor for the Ottawa Citizen who was then serving in South Africa.[67] The Guardian subsequently re-printed the excerpts in their own article titled, “A Canadian Officer On The Conduct Of The War,” on January 29, 1901.[68] Connie Hargrove in her capacity as a member of the literary committee of the South Africa Conciliation Committee, used the Guardian’s article for the Committee’s propaganda leaflet No. 65., “Horrors Of The War.”[69]

South Africa Conciliation Leaflet No. 65.[70]

Throughout the remainder of January, Ernest worked on American View, and gave occasional lectures in the vicinity of the New York (such as the Graduate Club in New Haven, and the Contemporary Club in Philadelphia.) After celebrating their second wedding anniversary, as guests of honor in a dinner hosted by Dr. George McClellan, the Hargroves traveled to Buffalo to finish Ernest’s tour.[71] Shortly after arriving in Buffalo, The Buffalo Evening News announced the death of Queen Victoria.[72] It was something that Ernest would address at the Contemporary Club the following day.[73] Ernest stated:

My profound and sincere belief is this, that if it had not been for that ruinous and abominable war the Queen would be alive today. Defend it? Never! The best that can be hoped for is this: That the English people, my own country, will realize before it is too late that they have been misled, that they have been lied to. Month by month. Year by year. Before this war and during this war. They have been deceived and have made a mistake in consequence.[74]

Ernest was loudly applauded, and, as The Catholic Union and Times stated: “The fact made plain that the citizen worth of Buffalo is with the Boers and against England in its unholy war. The fact was made doubly clear […] when Winston Churchill spoke for England at the Twentieth Century Club.”[75] Immediately after Churchill arrived in Buffalo, he was forced to address Ernest’s presence. During Churchill’s talk, an audience member interrupted: “Mr. Hargrove who lectured in this city last night said that the Boer would eventually win and be free.” To which Churchill replied: “Ah! The Boer will be free, but he shall not win. He shall be as free as I am, as you are, but South Africa shall be an Englishman’s land!” Churchill then declared that Ernest’s ideas were impracticable, “as the gist of his idea, held by many others, that a nation should never fight another nation unless the latter was much stronger and the former sure of defeat.”[76]

Ernest and Aimée left New York on February 9, 1901, on board the Cunard Line’s R.M.S. Lucania.[77] They arrived in Liverpool on February 16, concurrent with the arrival of John Aird, who was returning from Egypt to return to his duties in the House of Commons.[78] Simultaneous with the accession of King Edward, John Aird successfully turned back the water of the Nile. “The last channel has been closed at Assouan,” Aird telegraphed to London: “You can now walk across the Nile.” The contractor himself being “the first man ever to cross the Nile dry-footed.”[79] (During the construction Aird discovered an (alleged) six-thousand-year-old necklace; a necklace whose former owner appeared to Marie Corelli as an apparition.)[80] It had been a remarkable month for Ernest’s uncle; not only was he elected the first mayor of the city of Paddington, but during the New Year Honors he received a baronetcy from Queen Victoria—making Aird one of the last knights of the Victorian Age.[81] There would be little time for celebrating, for Ernest and Connie at least, as it was discovered that leaflet No. 65 was not as truthful as it had claimed. The Pall Mall Gazette broke the story on February 22, 1901:

Those responsible for “Kitchener’s Iron Hand,” as it appears in its “conciliation” garb, have not failed to add deft little literary touches of their own, supplying an adjective here, and a note of emphasis there. Worse still, in at least two instances whole sentences have been ingeniously interwoven into the grossly distorted narrative which the committee has issued broadcast as emanating from an officer of his Majesty’s Canadian forces.[82]

“It is of interest to give a list of officers of this pro-Boer committee,” wrote the Pall Mall Gazette, subsequently exposing Connie in the papers. Another paper, alluding to American Yellow Journalism would declare “British Pro-Boers Caught By A Yankee Trick.”[83] After a quick trip to Holland to meet with Dr. Leyds (and receive a stipend and supplies for his mission to Australia,) Ernest and Aimée left Southampton on March 9, 1901, on board the Griscom steamer S.S. New York.[84] It was a belated westward voyage. An explosion of a condenser had caused an ammonia leak, which resulted in the deaths of a steerage passenger, and one of the stewards. A superstitious mariner might suggest something otherworldly, for the S.S. New York was christened exactly thirteen years to the date of the accident by Jennie Jerome—Winston Churchill’s mother.[85] When the steamer finally “warped laboriously into her dock” on the evening of March 17, 1901, the New York Sun correspondent found Ernest and Aimée struggling with the customs officials at the pier. Their baggage, containing material for the Transvaal League, was “extensive” and the “inspectors were curious.” When pressed for his account of the voyage by The Sun, Ernest downplayed the severity of the incidents.[86] This was because the S.S. New York was a Griscom steamer, and the American Line could ill-afford bad press, especially after the incident with the S.S. Saint Paul, for, in a few short months, Griscom and J.P. Morgan would create a shipping merger known as the International Mercantile Marine.[87]

Thurston, Emil Neresheimer, Philo B. Tingley.[88]

Ernest and Aimée took different overland routes to California. It is unclear what events transpired in the days leading up to their eventual re-union in San Francisco, but following what few records we have, we can paint the following picture. It is likely that Aimée wished to see her parents, and Ernest, being on the outs with Emil and Tingley, was unwelcome in the Neresheimer home. The Neresheimer family was under strain. Besides the troubling treatment of Minnie, Fred Neresheimer’s home would be burglarized at least twice in between mid-March to mid-April, with over $2,000 worth of jewelry being stolen. It was believed that the house had been entered by means of a “skeleton key, as no doors or windows were found open.” There were no clues to the identity of the thieves, and the case was not reported to the police.[89] By September Fred would even shorten his surname to “Neres,” claiming “the name was too long for business purposes.” Given the string of misfortunes that followed the Neresheimer name, a change of identity might offer some protection.[90] Ernest was alone when he checked into San Francisco’s Palace Hotel on March 27, 1901.[91] He booked a ticket on board the Oceanic Line’s S.S. Sonoma, scheduled to launch on the March 27, but was delayed until March 30.[92] In those intervening days, on March 28, “Mrs. E. T. Hargrove of New York,” checked-in as a guest with a man named W.R. Edwards “a prominent society man of Santa Barbara” at the Westminster Hotel in Los Angeles.[93] The papers stated that she was Edward’s sister, which, of course, was untrue. Who the man was, and his relationship with Aimée, remains a mystery. The most charitable interpretation would be that Edwards was a pseudonym for Fred of Emil. Then on March 30, 1901, the day the Sonoma was scheduled for departure, Ernest checked-out of the hotel. The same day “Mrs. Hargrove [of] Chicago,” checked into the Palace Hotel (alone.) Then Ernest, once again, checked-into the Palace Hotel (alone.)[94] When the Sonoma finally set sail on March 30, 1901, both Ernest and Aimée were on board.[95] Aimée soon told Ernest that she “wanted [a child] very much.”[96]

HARGROVE

I. “Refined English Atmosphere.”

II. “The Purple Mother.”

III. “Kitty Tingley, Despot.”

IV. “Villa Maria.”

V. “Dr. Leyds And The Occultation Of World Politics.”

VI. “The South African Situation.”

VII. “The Conciliator Of South Africa.”

VIII. “Transvaal Vs. Churchill.”

IX. “The Séances Of Thomas Welton Stanford.”

X. “The White Stag.”

XI. “The Hair Line Of Duty.”

SOURCES:

[1] “Winston Spencer Churchill’s Tour.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) October 4, 1900.

[2] “Amusements.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) October 7, 1900; “Amusements.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) October 12, 1900.

[3] Tolppanen, Bradley. “A Vulgar ‘Yankee Impresario’– Churchill, Major Pond, And The Lecture Tour Of 1900–1901.” Finest Hour. (Autumn, 2016): 10-13.

[4] “Story Of China’s Crime.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) July 20, 1900.

[5] “The Passing Throng.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) October 7, 1900.

[6] [Ernest Temple Hargrove to James Burton Pond, Waldorf-Astoria, New York, New York, October 15, 1900.] James B. (James Burton) Pond papers, circa 1867-1934 and undated (2011M-47.) Houghton Library, Harvard University.

[7] “What Is Going On Today.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) October 8, 1900.

[8] “New York City.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) October 13, 1900.

[9] “Hargrove Back Again.” The Sun (New York) October 9, 1900; “Performance History.” Carnegiehall.org. The Carnegie Hall Corporation. Accessed February 24, 2020. https://www.carnegiehall.org/About/History/Performance-History-Search?q=&dex=prod_PHS&start=-2184778800.

[10] “Henry Ward Beecher was my nearest and dearest friend for eleven years. Excepting only Arizona and New Mexico, there was not a State or Territory in the Union in which we had not traveled together. In sunshine and in storm, by night, by day, by every conceivable mode of travel, in special Pullman cars, the regular passenger trains, mixed trains, freight trains, on steamboats and rowboats, by stage and on the backs of mules, I had journeyed at his side. I was near him in the days of 1876-77, at the time of his deepest sorrow, when he was reviled and spit upon; I saw the majestic courage with which- he passed through gaping crowds at railroad stations, and at the entrances of hotels and public halls—a courage which I had not conceived mere humanity could possess. I have looked upon him when I felt that I would give my poor life a thousand times could that sacrifice alleviate the mental sufferings that I knew he was undergoing. There were times when it seemed as though he must give way; times when I was the only friend within his reach, and he sought refuge near and with me. It was thus that he came to love and trust me, and that my love and veneration for him became so strong that to lose him left me like a ship without a helm or a commander. Especially during those three darkest years was he the subject of my sad admiration. Often have I seen him on our entering a strange town hooted at by a swarming crowd and greeted with indecent salutations. On such occasions he would pass on, seemingly unmoved, to his hotel, and remain there until the hour for his public appearance; then, confronted by great throngs, he would lift up his voice, always for humanity and goodness. He always saw and seized the opportunity to speak to the whole great people, and after he had spoken, the assemblages would linger to draw near, seemingly to touch the hem of his garments, to greet the man whom they had so lately despised. How changed I have often seen the public attitude toward him when he left a town to which he had come but the day before! Thus he went from city to city, meeting friends and advocates of all who heard or met him, and thus for eleven years was it my delight to accompany him in his work of re-establishing himself in that love and confidence of the people from which unprincipled enemies and an often merciless press had attempted to thrust him out forever. I thank God that it was my privilege to attend his fortunes to the end, and to see and to hear, on both sides of the continent and on both sides of the ocean, demonstrations of love and confidence that came at length in so unsullied and vast a stream from the church, his friends, his country, and his race, toward him who had brought many thousands of them much nearer than they had been to the common Master of us all.” [Pond, James B. Eccentricities Of Genius: Memories Of Famous Men And Women Of The Platform And Stage. G.W. Dillingham. New York, New York. (1900): 37-38.]

[11] “Oh set your hearts to the consideration of the incomparable unparalleled love of Jesus, in dying that cursed death of the cross for sinners. Consider and meditate, hold your hearts to it, until your hearts be affected with His love, His love that passeth the love of women, love passing understanding. And consider how well He deserves and how much He challenges your love. Consider once again, what a most lovely person Jesus is, who is altogether lovely, the ‘brightness of his Father’s glory, in whom dwells all fullness,’ Heb 1:3, and in whom is all power in heaven and earth, Matt. 28:18, and labor to affect your hearts with His most admirable excellencies, and then come unto Him weary and heavy laden with your sins, willing to part with them all; give up your whole selves to Him, give Him your whole hearts, and take Him for your Head and Husband, for your only Lord and Savior; enter actually into covenant with Him, to become His, and His alone, and His forever. Thus work out your salvation and your consolation, by believing in Jesus, in blessed, all-sufficient Jesus, trusting to Him, be trusting all with Him, and God will work in you ‘both to will and to do.’ Phil. 2:12, 13. Use these means in the strength of God, and doubt not, but in the use of them, you shall obtain this precious faith; which having and acting, you shall find it to be your heart’s ease in all your heart trouble.” —John Bunyan, “Heart’s Ease In Heart Trouble.”

[12] [Ernest Temple Hargrove to James Burton Pond, Waldorf-Astoria, New York, New York, October 15, 1900.] James B. (James Burton) Pond papers, circa 1867-1934 and undated (2011M-47.) Houghton Library, Harvard University.

[13] National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, D.C.; Soundex Index to Petitions for Naturalizations Filed in Federal, State, and Local Courts in New York City, 1792-1906 (M1674); Microfilm Serial: M1674; Microfilm Roll: 116.

[14] Boldt, George C. The Waldorf-Astoria, New York. Herbert Mitchell, Letter Press American Lithographic Co. New York, New York. (1903): Main Entrance: 20, Lobby: 22, Red Room: 28, Turkish Salon: 32; (Naturalization Paper) [National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, D.C.; Soundex Index to Petitions for Naturalizations Filed in Federal, State, and Local Courts in New York City, 1792-1906 (M1674); Microfilm Serial: M1674; Microfilm Roll: 116.]

[15] “Kruger’s Last Trek.” The Democrat And Chronicle. (Rochester, New York) October 20, 1900.

[16] Noel, Geoffrey C. “Politics In South Africa.” The Fortnightly Review. Vol. LXIX No. 8. (March 1, 1901): 508-519.

[17] “Mr. Ernest Temple Hargrove.” Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 22, 1900; “South African Blue Book.” The Times. (London, England) July 19, 1900; “News In Brief.” The Times. (London, England) October 16, 1900; “The Transvaal Concessions Commission.” The Times. (London, England) October 17, 1900.

[18] “Theosophical Marriage.” The Standard Union. (Brooklyn, New York) November 21, 1899.

[19] “Wealthy Men Back Silk Farm.” The St. Louis Post-Dispatch (St. Louis, Missouri) February 14, 1901.

[20] “Outrages At Point Loma.” Los Angeles Times. (Los Angeles, California) October 28, 1901.

[21] Portrait and Biographical Record of Arizona: Commemorating the Achievements of Citizens who Have Contributed to the Progress of Arizona and the Development of Its Resources. Chapman Publishing Company. Chicago, Illinois. (1901): 457-458.

[22] Hargrove, Ernest Temple. “Letters From W.Q. Judge: Pt. III.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXIX, No. 2 (October 1931): 107-122.

[23] “Every moment has its duty, and in the faithful performance of that duty you will find the satisfaction of your life. It may lead you to great achievement, or never beyond the humdrum monotonies of common existence. What matters it to you? The surface of things has no part nor lot in your considerations. That which lives when all else has passed away is the desire with which the man was working, not the results he accomplished. The good he loved and served endures forever; the good he strove to do more often dies. You who have learnt some what of paradox will not mistake me here. Meditation is not inaction; he who thinks so errs. But that which lives in action is the motive and the desire. The form it took passes as all form must, but the soul ‘of it reincarnates and fills with power and radiance all other forms that spring therefrom. In entering the higher life the disciple finds a great stillness, for his meditation is his life, not his deeds: and when with heart and mind and full consciousness he grasps the significance of this idea, then indeed he beholds a new heaven and a new earth.” [Cavé. “Fragment.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. VI, No. 8 (December 1900): 141.

[24] “St. Paul Loses A Propeller.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) November 5, 1900.

[25] Rochester Area Chamber of Commerce. Illustrated Rochester, 1898-1899. Rochester Chamber of Commerce. Rochester, New York. (1899): 149.

[26] “Mr. Ernest Temple Hargrove.” Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 22, 1900.

[27] “English Gentleman Talks Arbitration.” The Democrat And Chronicle. (Rochester, New York) November 8, 1900.

[28] The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Grand Staircase and Lobby, Hotel Touraine, Boston, Mass.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed June 26, 2021.

[29] “Experiences In Pretoria.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 1, 1900.

[30] [Bacon, Edwin Monroe. Boston Illustrated. Houghton, Mifflin, and Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1886): 92.] C.F. Willard writes: “When I got in, it was early and from newspaper habit I walked down to the front row of seats and sat less than 10 feet away from Judge and Annie. As she has seen fit to publish the E.S. instructions, it will not therefore be without justification that I relate what occurred, in order to give Judge his due. The room soon filled up with about 200 persons, and I noticed leaning up against the pedestal behind which Judge stood as presiding officer, so all could see and exposed for the first time, pictures of the two Masters, blessed be their name, for the knowledge they have given us. As he started to call the meeting to order, he leaned toward her, who stood on his right hand, and I heard him say to her in a low voice, ‘Sound the Word with the triple intonation.’ She replied in the same low voice, ‘I don’t dare to,’ or, ‘I don’t care to,’ but I think it was the first. I heard him say in a firm tone, ‘Then I will.’ He had been twirling his gavel in his hand but laid it down, stepped to his right, pushing her aside, and stepped to the side of the pedestal, facing his audience, with her behind him, and said: ‘I am about to sound the Word with the triple intonation, but before I do so, I have a statement to make which I do not care to have you speak to me about later, nor do I wish you to discuss among yourselves. I am not what I seem; I am a Hindu.’ Then he sounded the Word with the triple intonation. Before my eyes, I saw the man’s face turn brown and a clean-shaven Hindu face of a young man was there, and you know he wore a beard. I am no psychic nor have ever pretended to be one or to ‘see things,’ as I joined the T.S. to form a nucleus of Universal Brotherhood. This change was not one seen by me only, and we did not discuss the import of his significant statement, until after his death when a meeting was held in the Boston headquarters to determine our future action. Then I mentioned it in a speech and his statement, and fully ten persons from different parts of the hall spoke up and said, ‘I saw it too.’ ‘I saw and heard what he said,’ etc. That would seem proof enough about the borrowed body.” [Eklund, Dara (Compiler.) Echoes Of The Orient: Vol. I. Theosophical University Press. Pasadena, California. xxxv-xxxvi.]

[31] “Will Fight On.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) November 29, 1900.

[32] “The Great Crusade.” Theosophical News Vol I, No. 1 (June 22, 1896): 1-4.

[33] “Five Boer Refugees Reach New York.” The Great Round World And What Is Going On In It. Vol. XVI, No. 213 (December 6, 1900): 292-293; “Our Boston Letter.” Greenfield Gazette And Courier. (Greenfield, Massachusetts) December 8, 1900.

[34] “Krueger Thanks American League.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) December 13, 1900; Souvenir Of The South African Republics. Head Office Of The Boer Relief Fund For The Relief Of Boer Widows And Children. (1900.)

[35] “The Graduates.” The Technology Review. Vol. III, No. 1 (January 1901): 100-106; “The Technology Club.” The Technology Review. Vol. III, No. 3 (July 1901): 257-266; “The Graduates.” The Technology Review. Vol. III, No. 3 (July 1901): 338-341.

[36] “The Duty Of Nations.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 6, 1900.

[37] “The Technology Club.” The Technology Review. Vol. III, No. 3 (July 1901): 257-266.

[38] “Discipline In Army Brings Disasters.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) December 9, 1900; “Fighters Must Act for Themselves,” Press Conference, Everett House, New York, in Robert Rhodes James, ed., Winston S. Churchill: His Complete Speeches 1897-1963, 8 Vols. (New York: Bowker, 1974), I: 62.

[39] Hyslop, James H. The Ethics Of The Greek Philosophers. Charles M. Higgins & Co. New York, New York. (1903): vii.

[40] “Amusements.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 8, 1900.

[41] Mrs. Ole Bull. “The Cambridge Conferences.” The Outlook. Vol. LVI, No. 15 (August 1, 1897): 845-849; Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. “The Cambridge Conferences.” in Lewis G. Janes: Philosopher, Patriot, Lover Of Man. James H. West Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1902): 43-55; “Greenacre Conference.” The Bangor Daily News. (Bangor, Maine) July 1, 1902; “Death Of Mrs. Ole Bull.” The Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) January 21, 1911.

[42] Olcott, H.S. “Mr. Hargrove In South Africa.” Supplement To The Theosophist. Vol. XXII. (December, 1900): xii.

[43] “Lecture At Studio House.” The Cambridge Chronicle. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) December 15, 1900.

[44] “Mr. Churchill’s Lecture.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) December 13, 1900; “Churchill’s Debut.” The Standard Union. (Brooklyn, New York) December 13, 1900.

[45] “Mr. Churchill’s Lecture.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) December 13, 1900.

[46] Churchill, Winston. A Roving Commission: My Early Life. Charles Scribners’s Sons. New York, New York. (1930): 360.

[47] H. “Reviews: Great Contemporaries.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXXV, No. 2 (April, 1938): 163-173.

[48] (Twain) Portrait of Samuel Clemens, “Mark Twain” holding book., 1900. Copyright. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2018654589/.

(Churchill) Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill,-1965., ca. 1900. Photograph; Tolppanen, Bradley. “A Vulgar ‘Yankee Impresario’– Churchill, Major Pond, And The Lecture Tour Of 1900–1901.” Finest Hour. (Autumn, 2016): 10-13; Boldt, George C. The Waldorf-Astoria, New York. Herbert Mitchell, Letter Press American Lithographic Co. New York, New York. (1903.)

[49] Tolppanen, Bradley. “A Vulgar ‘Yankee Impresario’– Churchill, Major Pond, And The Lecture Tour Of 1900–1901.” Finest Hour. (Autumn, 2016): 10-13.

[50] Collins, J.F.L.. Collins’ Both Sides Of Fifth Avenue. J.F.L. Collins. New York, New York. (1910): 15.

[51] “Sympathy For The Boers.” The Wilkes-Barre Record. (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania) December 20, 1900; “Englishman For Boers.” The Baltimore Sun. (Baltimore, Maryland) December 20, 1900.

[52] “To Help The Boers.” The Sun. (New York, New York) December 20, 1900.

[53] “Sympathy For The Boers.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) December 20, 1900.

[54] “Editorials.” City And State. Vol X, No, 1 (January 3, 1901): 4.

[55] “Theosophical Boer Sympathizer.” The Democrat And Chronicle. (Rochester, New York) December 24, 1900.

[56] Perkins, David. A History Of Modern Poetry: From The 1890s To The High Modernist Mode. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. (1976): 580.

[57] “Sympathy For The Boers.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) December 20, 1900.

[58] Winston Churchill to Lady Randolph Churchill, December 21, 1900. Annotated typescript. Churchill Papers, Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge, U.K. (40). Winston Churchill in Boston 1900. J. E. Purdy.

[59] Winston Churchill to Lady Randolph Churchill, December 21, 1900. Annotated typescript. Churchill Papers, Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge, U.K. (40). Winston Churchill in Boston 1900. J. E. Purdy/ Detroit Publishing Co., Copyright Claimant, and Publisher Detroit Publishing Co. Tremont St. Street and the mall, Boston, Mass. United States Boston Massachusetts, None. [Cbetween 1900 and 1910] Photograph.

[60] Year: 1880; Census Place: Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Roll: 1170; Family History Film: 1255170; Page: 104D; Enumeration District: 122; Image: 0391; “1913 Anatomist Yearbook.” Jefferson Medical College Yearbooks. (1913): 8-10.

[61] “New Century Club.” The Official Office Building Directory and Architectural Handbook of Philadelphia. The Commercial Publishing and Directory Co. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1899): 180.

[62] “World’s Wars A Bar To Progress.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) December 31, 1900; “Editorials.” City And State. Vol X, No, 1 (January 3, 1901): 4; “Hargrove On Boer War.” Archibald Citizen. (Archibald, Pennsylvania) January 26, 1901; “Of Social Interest.” The Times. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) January 27, 1901.

[63] “Krueger Thanks American League.” The New York Times (New York, New York) December 13, 1900; Souvenir Of The South African Republics. Head Office OF The Boer Relief Fund For The Relief Of Boer Widows And Children. (1900)

[64] “The United States Greets United Australasia.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York.) January 1, 1901.

[65] “Cape Town Is Nervous.” The Sun. (New York, New York.) January 7, 1901.

[66] “Pro-Boer Leaflets.” Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) February 22, 1901.

[67] “A Four Days’ Trek After The Enemy.” The Citizen. (Ottawa, Canada) January 2, 1901.

[68] “A Canadian Officer On The Conduct Of The War.” The Manchester Guardian. (London, England) January 29, 1901.

[69] South Africa Conciliation Committee. The South Africa Conciliation Committee List Of Names And Addresses. National Press Agency. London, England. (1899): 3; “Horrors Of War.” The South Africa Conciliation Committee. No. 65. (February 1901.)

[70] “Horrors Of War.” The South Africa Conciliation Committee. No. 65. (February, 1901)

[71] “Personal Jottings.” The Morning Journal Courier. (New Haven, Connecticut) January 7, 1901.; “Mr. Ernest Temple Hargrove.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.) January 9, 1901; “Hargrove On Boer War” Archibald Citizen (Archibald, Pennsylvania) January 26, 1901; “Of Social Interest.” The Times. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) January 27, 1901.

[72] “Deathbed Scene At Osborne House.” The Buffalo Evening News. (Buffalo, New York) January 23, 1901.

[73] “Liberal Club.” The Buffalo Commercial. (Buffalo, New York) January 25, 1901; “‘White Man’s Burden’ A La E.T. Hargrove.” The Buffalo Evening News. (Buffalo, New York) January 25, 1901.

[74] Hargrove, Ernest Temple. “The White Man’s Burden,” in Addresses Delivered Before the Club During The Three Seasons, 1900-1903. Hausauer, Son & Jones, Printers. Buffalo, New York, (1904): 59-88.

[75] “Pot-Pourri.” The Catholic Union And Times. (Buffalo, New York) January 31, 1901.

[76] “Criticizes Kruger For Leaving Africa” The Buffalo Courier. (Buffalo, New York) January 26, 1901; “War Will Go On Under The King.” Buffalo Review. (Buffalo, New York) January 26, 1901; “Churchill On Boer War.” Buffalo Morning Express (Buffalo, New York) January 27, 1901.

[77] Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Inwards Passenger Lists. Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives of the UK (TNA). Series BT26, 1,472 pieces; “Ocean Steamers.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) February 18, 1901.

[78] “Court Circular.” The Times. (London, England) February 18, 1901.

[79] “Assouan As A Tourist Resort.” The Guardian. (London, England) February 21, 1901; “The Dam Across The Nile.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) February 10, 1901; “Utility And Beauty Ever Fighting.” The Christian Advocate. Vol. LXXVI, No. 9 (February 28, 1901): 324.

[80] Vyer, Bertha. Memoirs Of Marie Corelli. Alston Rivers Ltd. London, England. (1930): 186.

[81] “New Year Honors.” The Times. (London, England.) January 1, 1901.

[82] “Pro-Boer Leaflets.” Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) February 22, 1901.

[83] “Atrocity Making: British Pro-Boer Caught By A Yankee Trick.” The East Of Fife Records. (Fife, Scotland) March 1, 1901.

[84] “Shipping.” The Times. (London, England) March 10, 1901.

[85] “Launch Of An Inman Steamer.” The Liverpool Mercury. (Liverpool, Merseyside, England) March 16, 1888.

[86] Ernest said: “The stories about this seem to have been much exaggerated, you know. Why, we heard here that thirty or forty people had been killed. That’s all rot. There were two deaths. The whole trip before the first accident was very easy. We had only two rough days. After the ammonia explosion or whatever it was there was a burial at sea. I believe all the stewards attended. I wasn’t there myself. A collection was made for the benefit of the sufferers and about £100 I think, was raised. The second accident was really nothing, in fact we didn’t see anything of either, but nobody would have known about the shaft breaking at all if we hadn’t stopped. I was just being shaved in the barber’s shop just over where the thing broke. There was a slight jar and the man who was shaving me said ‘There’s something gone.’ Then he went right on shaving me.” [“The New York Met Mishap.” The Sun. (New York, New York) March 18, 1901.]

[87] “St. Paul Loses A Propeller.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) November 5, 1900; Flayhart, William H. The American Line: 1871-1902. Norton. New York, New York. (2000): 350; “The Ship Trust That Has Drawn Uncle Sam’s Fire.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) June 23, 1912.

[88] J.H.F. “Mirror Of The Movement.” Universal Brotherhood Path. Vol. XV, No. 6 (September 1900): 235-236.

[89] “Burglaries At Flushing.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York) April 16, 1901; “Long Island News.” The Brooklyn Citizen (Brooklyn, New York) April 16, 1901.

[90] “Flushing Doctor Changes His Name.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) September 26, 1901.

[91] “Hotel Arrivals.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) March 27, 1901.

[92] The San Francisco Call stated the delay of the Sonoma was because of “some accident to her machinery.” The Honolulu Republican stated that the Sonoma “was forced to wait two days for the English mail in San Francisco.” [“Along The Waterfront.” The Honolulu Republican. (Honolulu, [Oahu]) April 6, 1901.]

[93] “Personal.” The Los Angeles Times. (Los Angeles, California) March 28, 1901.

[94] “Hotel Arrivals.” The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco, California) March 30, 1901; “Hotel Arrivals.” The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, California) March 30, 1901.

[95] “Passengers For Australia.” The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco, California) March 30, 1901.

[96] Last Will and Testament of Ernest Temple Hargrove.