In Brussels, the Hargrove’s visited Dr. Leyds in Holland where Ernest received a commission from to ghostwrite Leyds’s book, The First Annexation of the Transvaal.[1] They then went to Brussels, where Leyds was living, to begin work on the manuscript.[2] On January 18, 1902, Leyds and members of the Boer delegation conferred at Scheveningen in preparation for peace talks at the Hague on January 20, 1902.[3] Ernest was likely one of the “Englishmen supposed to be officials of the British government [who] arrived at the Hague under assumed names.”[4] On February 5, 1902, Aimée gave birth to a baby boy. They named him William Archibald Temple, after William Quan Judge and Archibald Keightley. (They called him “Temple” for short.)

Dr. Leyds In His Study.[5]

On May 31, The Treaty of Vereeniging marked the end of the Boer War. Ernest accepted the peace reluctantly and suggested that the Boer government-in-exile repudiate it. To add insult to injury, Louis Botha downplayed the effectiveness of W.T. Stead, Cambell-Bannerman, and the rest of the pro-Boer party in England. “They did not help us,” said Botha. “Their talk and the rest was not of the least value to the burghers in the field.” Ernest thought this was a cavalier dismissal of men who could potentially have a decisive place when the Liberals. “The only thanks these people have had so far (and some of them risked their neck) was to be told in a cable from Natal that Botha had said he had no use for them, or line to that effect,” Ernest told Leyds. After the war Ernest assisted Leyds in acquiring blue books and other literature for his collection, but he was suffering from mental and physical fatigue.[6] “It was very unfortunate that [Ernest] should have gotten that commission,” according to Aimée. “It was such a deadly dull affair […] It absolutely ruined his ego […] I was busy with the baby, and he was having an awful time with the book, and well, it eventually resulted in his breaking down in his health.”[7]

With his mental and physical health deteriorating, Ernest, Aimée, and Temple went to the renowned sanatorium of the naturopathic physician, Dr. Heinrich Lahmann in Weiße Hirsch, just outside of Dresden.[8] One patient at the time described the setting like this:

At Weißer Hirsch the patients learned to brave all weathers with minus clothing, and thereby gain maximum strength of vigor. The men all took long walks in the woods through wind, rain, snow, clad only in a bathing-dress, boots and sandals. The women soon leave the indoor air-bath for the unroofed enclosures where they could walk, run, chop or saw wood, play ninepins, or exercise dressed only in a muslin chemise, and the verdict was those who have tried it is that the body becomes more easily warmed than when fully clothed, owing to the stimulating effect of the air upon the skin, which aided the circulation of the blood.[9]

Minnie Neresheimer (Aimée’s mother) was an advocate for naturopathy, and Ernest was aware of such treatment from his time at Franz Hartmann’s “Inhalatorium.”[10] Ernest received a rest treatment Dr. Eugen Weidner at Lahmann’s Sanatorium in Weißer Hirsch.[11] Lachmann’s treatments were based on nutritional reform, hydrotherapy, and outdoor physical exercise. To accommodate the guests, Lahmann provided decentralized housing in the form of ten villas including the “Heinrichshof,” the family residence.[12] Aimée and Temple lived in the Heinrichshof while Ernest lived in a separate while he underwent a rest-cure. The family met at mealtimes, and occasionally they would pass each other on the street, but outside of those encounters, they saw very little of each other for long stretches of time.[13] “Ernest,” Aimée asked, “what is the matter?” “Tuberculosis, I believe,” Ernest grimly replied. “Please, let the matter drop.”[14] The treatments began to help a little, but Ernest became fixated on the novel health practices, like the “Cooking Reform” advocated by Lahmann his work, Natural Hygiene.[15] Ernest subsequently refused to eat anything but sterilized food, and purchased a steam-cooker with which Aimée “sterilized” all his food.

Heinrich Lahmann.[16]

The Hargroves left Utrecht and moved to Paris where Ernest would finish The First Annexation of the Transvaal. It was for a change of scenery, for Ernest and Aimée, both of whom were depressed and “rather lonely.” To alleviate wis wife’s loneliness, Ernest invited his sister, Connie, to stay with them for several weeks at a time.[17] In December John Aird traveled with Winston Churchill from London to Egypt to attend the opening of the Aswan Dam, and though he wished it could have been him accompanying their uncle, Ernest committed to his promise to Leyds.[18] At this time Ernest was asked to return to America by the dissidents of the Tingley Theosophists to “reopen the war against Mrs. Tingley.”[19] Though he declined the invitation, Aimée was aware, in some capacity at least, that her husband was still involved with the Movement.[20]

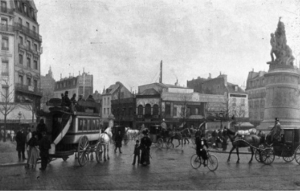

Paris.

After leaving Utrecht the previous summer, the Hargroves moved to Paris (sometime in November in 1903) Ernest hoped that the change of scenery might alleviate Aimée’s loneliness and depression. Strolling through the boulevards, on that mid-November day, was, indeed, a welcome respite. Ernest, who was still working on Leyd’s book, had made life unbearable, and the atmosphere at home was an admixture of intensity and suffocating boredom. Admiring the glamorous French ladies, wrapped in furs, and radiant with jewels, Aimee’s heart singed—a heart, it must be said, already charred from the slow-fire of melancholy. It was not the fear of never wearing a gown again, which Aimée felt, nor was it the fear that she would never sing in an Opera House. That peculiar needle, the Tour Eiffel, grew ever larger as they approached the Champ de Mars, and it seemed as if all of Paris, those interested in aeronautics at least, made the pilgrimage to the Galerie des Machines to witness, first-hand, the miracle of Pierre Lebaudy’s steerable airship, the “Jaune.”

“Jaune.”

Aimée almost wished that Connie was with them, so that she too could experience the event. But that feeling passed and was replaced with a sincere gratitude for her sister-in-law. Connie, who lived with them a few weeks at a time, had remained in the apartment with Temple so that she might have some time alone with her husband on her 21st birthday. As frustratingly peculiar as Ernest could be, she was still captivated by his—earnestness. The crowd at Champ de Mars was an even sea of top hats and plumed millinery, a placidity of horizon broken by the only thing shorter than the Tour Eiffel—her husband. She listened, even permitting a faint smile, as Ernest explained (with his characteristic lack of social-awareness,) his own views on aeronautical science. With demure nods, and batted lashes, Aimée gracefully admitted her ignorance about such topics; likewise, she was graciously silent about her doubts as to whether Ernest was any less ignorant on the subject. The “Field of Mars,” was worlds away from Bayside, but something today, something not entirely explainable to herself, she felt as she once had, when Ernest explained the magic of the universe on the docks of her father’s house. She remembered something Connie said a few weeks earlier: “You really ought to have another baby soon.” Temple was getting a little older, Connie reasoned, and the children would be companionable to each other. Perhaps she was right. Nesting her tiny fingers inside her husband’s hand, she announced a smile to Ernest. Given the opportunity, Ernest could fill entire lectures with elaborate theories—words upon words about the mysteries of creation. A lingering glance was all that Aimée required. In excited anticipation, Aimée tightened her grip, ever so slightly, as the stern of the “Jaune” entered the clouds over Ville de L’amour. Aimée then went Dresden. Ernest joined her not long after.[21] Ernest’s father, James Sidney Hargrove, died in London, in April 1904.[22] It was around this time that Ernest accused Aimée “of being indiscreet in her associations with persons” with whom Ernest previously approved. Namely a man in Chicago and Dr. Weidner.[23] Perhaps this was due to the fact that Aimée had given birth to another child in August 1904, a daughter named Joan Leona Constance Hargrove.

Ernest sat for hours, behind a locked-door, working on the book that Dr. Leyds had commissioned him to write. He was among good company, as writers such as Rainer Maria Rilke were also there.[24] The First Annexation of the Transvaal was eventually completed in 1905, and as was the case with Keightley’s book, this work was attributed to another writer—Dr. Willem Johannes Leyds.[25] By this time, however, the family had run out of money. With no other options, Ernest, Aimée, and the children returned to America in 1905 to live with Aimée’s family in Colorado. (More here)

HARGROVE

I. “Refined English Atmosphere.”

II. “The Purple Mother.”

III. “Kitty Tingley, Despot.”

IV. “Villa Maria.”

V. “Dr. Leyds And The Occultation Of World Politics.”

VI. “The South African Situation.”

VII. “The Conciliator Of South Africa.”

VIII. “Transvaal Vs. Churchill.”

IX. “The Séances Of Thomas Welton Stanford.”

X. “The White Stag.”

XI. “The Hair Line Of Duty.”

SOURCES:

[1] Leyds, Johannes Willem. The First Annexation of the Transvaal. T. Fisher Unwin. London. (1906.)

[2] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove As a Will of Real and Personal Property; Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York, First Department Jun 27, 1941; 28 N.Y.S.2d 571 (N.Y. App. Div. 1941.)

[3] “The Boer Peace Rumors.” The New York Times (New York, New York) January 18, 1902; “Effort To End The Boer War.” The Democrat And Chronicle. (Rochester, New York) January 20, 1902; “The War.” The Guardian. (London, England) January 20, 1902; “The Boer Delegates.” The Times. (London, England) January 20, 1902; “Boer Delegates Decision.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) February 12, 1902.

[4] “Boers In Dire Straits.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) January 20, 1902.

[5] Gribayedoff, V. “Cuba And The Transvaal—A Comparison By Dr. Leyds.” Collier’s Weekly. Vol. XXIV, No. 23. (March 10, 1900): 9.

[6] Davey, Arthur. The British Pro-Boers 1877-1902. Tafelberg Publishers. Cape Town, South Africa. (1978): 120, 186.

[7] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove.

[8] The ascetic aspects of a stay last the sanatorium were framed by the promises of luxury and consumption. This was all the more important because the sanatoria had to negotiate between the somewhat contradictory expectations and desires of their clients. On the one hand, patients expected that they had to live according to some life-reform prescriptions of the ascetic life: diet, exercise, even painful therapies such as electro-shock treatments, and alternative therapies such as Sebastien Kniepps’s cold-water therapy. When Thomas Mann, for example, attended Lahmann’s sanatorium, he wanted to take care of himself a little bit’ and hoped that he would be inspired by some of the ‘applications.’ The success of sanatoria might be taken as an indication that health reform asceticism provided real relief for patients. The pleasure associated with therapeutic relief was one on the main reasons why many people were prepared to submit to ascetic health regimens in the first place. This was true not only for those who could afford to attend expensive sanatoria. A large number of the less affluent members of the natural-therapy associations went to natural therapists for cures, or merely purchased therapy manuals or healthcare products for self-administered cold-water (Selbstbeherrschung) For those who turned to life reform because of psychological conditions like neurasthenia, hysteria, or hypochondria, an ascetic health regimen promised relief. Health reformers described their regimes in terms of hard work on their selves that eventually would be rewarded. By strengthening their bodies, they would overcome their own inner weaknesses and softness and harden their bodies as well. [Hau, Micael. “Asceticism And Pleasure In German Health Reform: Patients As Clients In Wilhelmine Sanatoria.” Essay. In Beyond Pleasure: Cultures of Modern Asceticism. (eds.) Evert Peeters, Leen Van Molle, and Kaat Wils. Berghahn Books. New York, New York. (2011): 42–61.]

[9] Fernor, Mary. “Nature To The Rescue.” The Royal Magazine. Vol. XII. (May 1904-October 1904): 209-213.

[10] (Minnie): “Barefoot Kneippist.” The Topeka State Journal. (Topeka, Kansas) October 1, 1896; (Hartmann): [H.T.P. “The Stop At Interlaken” The Theosophical News Vol. I No. 16 (October 5, 1896): 1-3; E.T.H. “The Screen of Time.” Theosophy. XI, No. 7 (October 1896): 193-198; “The Crusade.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. II, No. 6 (October 1896): 95-95; “The Crusade.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. II, No. 7 (November 1896): 110-112.] Hartmann’s impact would result in more profound ways in 1905—when Guido Von List, the inventor of Rune Magic, with the support of Hartmann, would appropriate Theosophical cosmology for the project of constructing a mythic past for the German peoples. The result would be the linking of the “Aryan” people with the “Tuetonic” peoples and thus use of the Theosophical swastika as their symbol. A belief known as Ariosophy, a precursor of Nazi esoteric fascism emerged, and Theosophy would become guilty by association thereafter. [Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. The Occult Roots Of Nazism. New York University Press. New York, New York. (1993): 28-31, 49-51.]

[11] Eugen Weidner, a protege of Dr. Lahmann at Lahmann’s Sanatorium in Weißer Hirsch see Karlheinz Blaschke, Uwe John, Reiner Gross, Holger Starke [Theiss] Geschichte der Stadt Dresden, Volume 3. Dresden, Germany. (2005): 356; In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove, Deceased, As a Will of Real and Personal Property.

[12] Biografie des berühmten Dresdner Naturheilers Dr. med. Heinrich Lahmann (1860–1905). In: Lahmanns Dresdner Kochbuch. Edition Krickau, Dresden (2001): 288–292, 303.

[13] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove.

[14] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove.

[15] Lahmann, Heinrich. Natural Hygiene, Or Healthy Blood. Swan Sonnenschein. London, England. (1898): 216-232.

[16] Lahmann, Heinrich. Natural Hygiene, Or Healthy Blood. Swan Sonnenschein. London, England. (1898): 204.

[17] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove.

[18] “Our London Correspondence.” The Guardian. (London, England) November 19, 1902; “The Nile Barrage.” The Guardian. (London, England) December 10, 1902.

[19] “Will Fight Mrs. Tingley.” The Sun. (New, York, New York) November 9, 1902.

[20] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove.

[21] “Lebaudy Airship’s Feat.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) November 14, 1903; “Paris Lauds New Aeronaut.” The Ottawa Journal. (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) November 16, 1903; “The Lebaudy Airship.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) November 15, 1903; The Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove.

[22] Ancestry.com. England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

[23] The Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove.

[24] Lachmann’s sanatorium achieved world acclaim in a very short time; the number of patients who arrived over the years grew exponentially, in 1893 over 1000 patients, 1897 over 2000, 1901 over 3000, in the year of Lachmann’s death in 1905 (Lahmann died a month after the Hargrove’s departure for the United States) nearly 4,000 patients were treated. Franz Kafka, Thomas Mann, and Rainer Maria Rilke were among the notable guests. Joan Leona Constance Hargrove was born in Dresden in August of 1904 during the Hargrove’s second stay in the sanitarium; the family did not leave Germany until late April of 1905. There is a possible overlap of two months which coincide with Rilke’s second stay with Lachmann. [“Rainer Maria Rilke to Lou Andreas-Salomé in Göttingen.” Rainer Maria Rilke to Lou Andreas-Salomé. March 31, 1905. In Rilke and Andreas-Salomé: A Love Story in Letters. W.W. Norton & Company. New York, New York. (2008): 145.]

[25] Leyds, Johannes Willem. The First Annexation of the Transvaal. T. Fisher Unwin. London. (1906.)