Towards the end of March 1898, Tingley issued a notice to the stockholders of the West Virginia Corporation, including Spencer and Ernest, which called for a stockholder meeting for April 9, 1898. The purpose, it was stated, was the election of directors. According to the Constitution of the Corporation, however, the directors could only be elected at a regular annual meeting, and the date for the annual meeting had already passed. This was to the first stockholders meeting since their initial meeting for incorporation in 1897. Ernest and Spencer felt that they should be in a position to render some formal account to the subscribers, and wrote to Emil on March 25, 1898, asking him to designate a time and place at which they could inspect the account books of the corporation. Emil did not reply. They made another appeal to Emil on March 28, 1898, at which time Emil wrote to Spencer that he had heard from Tingley that Spencer was no longer a stockholder and wrote Ernest saying that he was leaving New York on a train and would be away “for some time” and would discuss the matter with Ernest upon his return. Emil would never discuss the matter with Ernest.

Failing to conform to his promise, Ernest’s lawyer called upon Emil on April 4, 1898, “in order to lay before him his legal and moral duty, as Treasurer, to allow his fellow director an inspection of the Corporation’s books.” Emil stated that he was powerless to do anything in the matter without first gaining the permission of Tingley, and that his own lawyer would communicate Tingley’s decision to Ernest’s lawyer as soon as possible. Because new directors were to be elected in five days, a prompt communication was necessary, but, once again, no communication was made.

On April 6, 1898, Ernest paid a visit to Emil’s office and “made a verbal and formal demand to inspect the books of the corporation.” Emil refused. Ernest then applied for a peremptory mandamus to compel Emil to grant the inspection. On April 9, 1898, the stockholders’ meeting was held at Aryan Hall. Ernest, Spencer, Emil and Pierce were in attendance with H.T. Patterson acting as Secretary; Tingley refused to enter the room. Tingley, Emil, and Pierce were nominally elected directors, Ernest, and Spencer, all the while, protesting against the illegality of the proceedings. Ernest’s motion for a mandamus was heard only after he and his lawyer were away from New York. Emil made affidavit that Ernest’s motivation for instituting the proceeding was to harass Tingley and himself, and that Ernest “was actuated by disappointed ambition because he had not been elected President of the T. S. in A.” The allegations had no bearing upon the case, nor upon the decision, however, because of the absence of Ernest and his lawyer, Emil made another sworn statement, un-contradicted, which did have a direct bearing on the outcome of the case—that Ernest was not a stockholder in the corporation. Left unchallenged, Emil’s sworn statement carried weight, and Ernest’s motion was denied in his absence. Spencer was soon notified that he was no longer Secretary.[1]

This, of course, did not endear Ernest to Emil, and troubled Aimée. A friend from Villa Maria tried to console her: “You know, that [Hargrove] is emphatic about things that do not require emphasis. It is a Spanish fault, but the Spaniards wear it gracefully, like the folds of their capes. Hargrove is an Englishman!” Aimée wrote to Minnie, confessing that she still loved Ernest, and pleaded for her help.[2]

The first week of April 1898, “war spirit developed rapidly.” On April 5, in light of the critical relations between Spain and the United States, the United States asked the British charge d ’affaires at Madrid to assume charge of American interests in Spain. The next day, representatives of the “Six Powers,” (Great Britain, Germany, France, Austria-Hungary, Russia, and Italy,) addressed a note to the American government in in the interest of peace. On April 8, the London Times felt it necessary to explain that Great Britain’s peace signature was “in no way hostile to the United States.” Rumor was swirling that the “United States had resented this action as unwarrantable interference with her responsibilities was considered in the House of Commons.”[3]

On April 18, 1898, Ernest gave a free lecture titled, “An Anglo-American Alliance,” at Rauscher’s Restaurant, in Washington, D.C.[4] In his talk, Ernest stated that entire system of international law was predicated on the basis that nations share mutual interests; that they must have relations with one another. “Cut oil from Europe and Asia, America would be ruined. Its interests had grown immensely during the past ten years in China, and with a canal across the Isthmus it would reach enormous proportions.” Ernest argued that it was not only in the interests of America and England, but Canada, Australia, and the rest of the anglophone world.[5]

On the morning of May 29, 1898, the Convention of the Theosophical Society in America opened at the Grand Hotel in Cincinnati.[6] A letter from the mysterious Outer Head was read to the members of the School:

The Masters are both displeased and disappointed with the School as a whole […] The School will have to submit to a period of silence, of darkness, of discouragement. Only those who can get beyond the outer clouds and reach the inner Light which always is burning will be able to find light during this time […] when this test of silence is ended . . the School will be more truly an occult body than ever before; entrance to it will be much more difficult; rigid probations and examinations will be required.[7]

Ernest decided to remain in New York, and not attend the Convention. He instead sent a letter of greeting, in which he wrote: “Though it will not be possible for me to attend this Convention in person, I desire to convey to you my heart-felt good wishes for the success of your deliberations. It has fallen to your lot to ‘keep the link unbroken.’ I am sure that you will do it.”[8]

He then went to England for a few weeks to spend some time with his family. It was announced in late-February, during the height of the troubles with Tingley, that John Aird’s firm had finally been awarded the contract from the Khedive to build the proposed Aswan Dam—news that would certainly have been of immense interest to Ernest.[9] While there, Arch and Julia invited Ernest to live with them in the coming months and offered a commission to write a book for Arch, The Recovery of Health, under Arch’s name.[10] As Aimée would later state: “[Arch] was very busy and couldn’t take the time to write the book himself; and at the same time, it gave [Ernest] a means of livelihood treatment.”[11] Ernest also developed a syllabus for the weekly meetings of the English T.S. for the ensuing season; it was a series of questions and prompts designed to stimulate metaphysical discussion.[12] In July, 1898, Ernest warned the faithful Theosophists that after the New Year he would sever his connection with the administration of affairs. He also said that after his trip to England, might return to practice law in the States.[13]

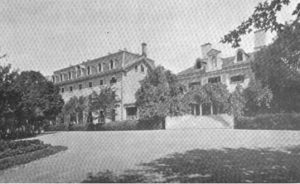

Villa Maria Convent, Montreal Canada. c.a. 1898.[14]

Ernest did return to the States, arriving in New York on July 24, 1898, on the Hanrigen Liuse.[15] He did not go into law, however, instead he talked with Minnie Neresheimer, and “finally persuaded her to give her consent.” Minnie knew that Aimée was grieving over Ernest, and she was sympathetic to this young love. Though she was loyal to Emil, she refused to join Tingley’s Universal Brotherhood.[16] Minnie was suspicious of the growing influence Tingley was wielding over Emil, and she had every reason to believe that this self-styled “Purple Mother” played a role in her husband’s decision to send Aimée to Villa Maria as a retaliation against Ernest’s perceived “disloyalty.” Minnie decided that she would disobey Emil and Tingley, and escort Ernest to Montreal.[17] The trip was a success.[18] It was agreed that when Aimée returned home for Christmas holiday, she and Ernest would be married, and move to England. Emil, upon discovering the news, was furious; he told Aimée that he would not speak to her again if she followed through with the wedding. Ernest sent a message to Emil, via Minnie, stating that he would “simply treat [Aimée] as a sister, until [she] was older.”[19]

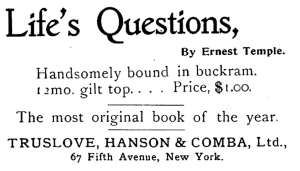

Life’s Questions.[20]

Ernest further distanced himself from the Theosophical movement, in public at least, and published two works in the autumn and early winter of 1898 to earn some income. Both of which received favorable reviews.[21] The first of these works was a collection of the questions he used for the English T.S., titled “Life’s Questions,” under the pen-name, Ernest Temple. In the preface, Ernest writes:

There are many thousands of men and women at the present time whose chief aim in life it is to make other people think and believe as they do. They are deeply convinced that they possess the Truth, and that it is their bounden duty to preach the Truth as they see it. While the motive which prompts this widespread activity is often pure and unselfish, and while the results achieved are often excellent, it is much to be regretted that so few efforts are made to inspire others to think for themselves.[22]

Ernest’s second work, World Politics, was written under the pen-name “T.,” which caused “considerable speculation.”[23] In the work Ernest argues for the creation of an international court with the authority to enforce its decision predicated on a careful study of the evolution of law-controlling States and their relations. Ernest tells us in the addendum of World Politics, that the work was completed sometime before August 1898, when Czar Nicholas II made an appeal for an International Conference to ‘cement an agreement by a corporate consecration of the principles of equity and right, on which rest the security of States and the welfare of the peoples.’” Ernest also cryptically stated:

A dozen determined men believing in themselves and their mission, can mold the thought of the age in which they live. One man has done it before now. Four men revolutionized the thought of the English-speaking world in less than a quarter of a century. These may be exceptional cases both of men and of missions, but the humblest and least of men, able to make one simple fact his own, must come in time to understand that he and his fact between them may constitute a world-moving power; and when not only the men and the thought are ready, but the time is ripe for the doing of the deed then nothing can withstand a movement which great nature has made her own. Whether the conclusions put forward in this brochure be approved or disapproved, they should not be devoid of interest, if only because they will be made national political issues in most of the leading European countries and in the United States of America within the next few years. This may seem an idle boast and an empty prophecy; but nothing could be gained by deliberately forecasting such an event if overwhelming probability did not point to its occurrence. There has been in existence, for some time past, a private body, with a membership scattered throughout the world, working to bring this about. The members of this organization will not reveal their connection with it, but those who know them know that their influence is sufficient to guarantee that the matter shall be submitted to the people.[24]

Ernest was, perhaps, talking about the E.S.T. On October 17, 1898, Ernest wrote to the members of the School:

Already I have been instrumental in “introducing” the Outer head to the members, I have not yet “introduced” the members to the Outer Head; and this has to be done in due form…This is one way of saying that the School must be organized. Now you already know that the Outer Head will confine himself to aiding those members who appeal to him for guidance in their studies and in their interior development; that he will not attend to the routine work.

In December 1898 a Reference Committee of the Eastern School was established by Ernest to administer the work for the benefit of the members. And it was Ernest, not the Outer Head, who appointed this Committee which consisted of William Ludlow, C.A. Griscom Jr., Charles Johnston, Archibald Keightley, J.D. Buck, George Coffin, and A.P. Buchman.[25]

Elsewhere in New York, Frances J. Myers declared that both Tingley and Ernest were “cut off by the Higher Powers,” and that a new body, called the “Temple” had been formed as the “new and true occult school from which trained students are to be sent forth to work among the masses.”[26] In the city, John M. Pryse, President of the White Lotus Theosophical Society, passed resolutions to withdraw from the Universal Brotherhood, on the ground “that the work of disseminating theosophical philosophy has been impeded by continual contentions.”[27] (Pryce’s short-lived group would be known, initially, as the White Lotus Theosophical Society, but would later adopt the name Eclectic Theosophical Society. It was an independent international body with Pryse as its President, and its headquarters at his home, 17 W. 98 Street, New York. Dr. Buck’s group, until 1905, were known as the American Theosophical Association.)[28]

With his wedding day approaching, Ernest donated his complete collection of the standard books and magazines on Theosophy, as well as several rare volumes, to the Griscom T.S. He suggested the collection be used as the nucleus of a circulating library, which would be sent on loan to any member of the Society in America in good standing upon payment of postage, and a small fee of a few cents. This library would further grow with the addition of William Ludlow’s collection.[29]

According to Aimée, just before the wedding, Ernest told her on the dock at Bayside, “that he was Napoleon and that [Aimée] was Josephine—and that [they] must carry on [their destiny] together. He had an idea that he had a great destiny to fulfil.”[30]

HARGROVE

I. “Refined English Atmosphere.”

II. “The Purple Mother.”

III. “Kitty Tingley, Despot.”

IV. “Villa Maria.”

V. “Dr. Leyds And The Occultation Of World Politics.”

VI. “The South African Situation.”

VII. “The Conciliator Of South Africa.”

VIII. “Transvaal Vs. Churchill.”

IX. “The Séances Of Thomas Welton Stanford.”

X. “The White Stag.”

XI. “The Hair Line Of Duty.”

SOURCES:

[1] E.T.H. “Legal News.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. IV. No. 1. (May 1898): 12-15.

[2] “Bond Of Theosophy.” The New York Journal. (New York, New York January 18, 1899.

[3] “Four American Powers Bought At Once.” The New York Journal. (New York, New York) April 15, 1898; Reuter, Bertha Ann. “Anglo-American Relations During The Spanish-American War.” Dissertation, University Of Iowa, (1923): iv-19.

[4] “An Anglo-American Alliance.” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.) April 16, 1898; “Anglo-American Alliance.” Arizona Republic (Phoenix, Arizona) April 26, 1898.

[5] “An Anglo-American Alliance.” The Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.) April 16, 1898; “Anglo-American Alliance.” The Arizona Republic. (Phoenix, Arizona) April 26, 1898.

[6] “Theosophists.” The Cincinnati Inquirer. (Cincinnati, Ohio) May 30, 1898.

[7] Cooper, John. “The Esoteric School Within the Hargrove Theosophical Society.” Theosophical History. Vol. IV, No. 6-7. (April 1993-July, 1993):178-186.

[8] “Theosophical News And Work: The Convention.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. IV. No. 2. (June 1898): 7-15.

[9] “Money Matters.” The Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art. Vol. LXXXV No. 2209. (February 26, 1898): 293-295.

[10] Keightley, Archibald. The Recovery Of Health: With A Chapter On The Salisbury Treatment. Henry J. Glaisher. London (1900.)

[11] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove.

[12] “Theosophical News And Work: The H.P.B. Theosophical Society.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. IV, No. 9 (January 1899): 12-13.

[13] “Hargrove-Neresheimer.” The Times Democrat. (New Orleans, Louisiana) January 18, 1899.

[14] Drummond, J.E. “A Famous Canadian Convent.” The Dominion Illustrated Monthly. Vol. II, No. 6. (August-September, 1893): 413-418.

[15] Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Outwards Passenger Lists. BT27. Records of the Commercial, Companies, Labour, Railways and Statistics Departments. Records of the Board of Trade and of successor and related bodies. The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, England.

[16] “Sun Worshippers of Point Loma.” The Detroit Free Press. (Detroit, Michigan), November 16, 1902.

[17] Villa Maria, the stone mansion school founded by Marguerite Bourgeois for the Sisters of the Congregation of Notre Dame, was located at the “Monklands,” a grouping of buildings midway under the plateau of the westerly spur of Mount Royal. The property once belonged to Lord Elgin when he was Governor-General of Canada. In 1852 the property was acquired by Les Dames de la Congregation de Notre Dame, who preserved Elgin’s mansion intact. The new proprietors, however, transformed the ball-room and a dining-room, into a chapel and music hall. They also built the large Convent of Villa Maria, which opened as a boarding-school in September 1854. There were 200 boarders at Villa Maria, representing almost every nationality—girls from Spain, France, Cuba, Italy, all over Canada, and from the remotest states of the union. The discipline of the students was excellent; the girls were taught by a knowledgeable staff of fifty teachers, special courses in science, languages, drawing, painting, elocution, and music—both vocal and instrumental. The junior department is watched over with maternal care and the child soon acquire French without any effort. At the time when Ernest and Minnie arrived, they would have been met with the picturesque ruin of pale grey limestone, the result of a fire in 1893 when a large segment of the convent was lost. [Drummond, J.E. “A Famous Canadian Convent.” The Dominion Illustrated Monthly. Vol. II., No. 6. (August-September, 1893): 413-418; “Old Monklands.” The Gazette. (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) January 7, 1898; “Visiting Monklands.” The Gazette (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) June 13, 1898; Wright, Emma A.“A Famed Old Convent.” The Journal News (Hamilton, Ohio) February 18, 1899.]

[18] “Bond Of Theosophy.” The New York Journal. (New York, New York January 18, 1899.

[19] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove.

[20] “Front Matter.” The Artist: An Illustrated Monthly Record of Arts, Crafts and Industries (American Edition) Vol. XXV, No. 236 (1899).

[21] “Miscellaneous Books.” The Glasgow Herald (Glasgow, Scotland) December 21, 1898; “Life’s Questions” Book Notes. Vol. II. No. 1. (January 1899): 53.

[22] Temple, Ernest. Life’s Questions. Trustlove & Comba. New York, New York. (1898): 3-6.

[23] “Peace Lecture By ’T.’” The New York Herald—French Edition (Paris, France) May 16, 1899.

[24] T. World Politics. R.F. Fenno & Company, New York City. (1898): 151-152.

[25] Cooper, John. “The Esoteric School Within the Hargrove Theosophical Society.” Theosophical History. Vol. IV, No. 6-7. (April 1993-July 1993):178-186.

[26] “Cuttings And Comments.“ The Theosophist. Vol. XX, No. 6 (March 1899): 380-384.

[27] “Call For Convention.“ The Inter-Ocean. (Chicago, Illinois) January 28, 1899.

[28] Benson, John Lossing, ed. “Theosophy.” In Harper’s Encyclopaedia of United States History from 458 A. D. to 1902. Vol. IX. Harper & Brothers . New York, New York.(1902): 66-67.

[29] “Theosophical News And Work: The H.P.B. Theosophical Society.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. IV. No. 9. (January 1899): 13-14; “Free Lending Library.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. I, No. 2. (July 1904): 69-70; “T.S. Activities.” The Theosophical Quarterly Vol. IV, No. 1 (July 1906): 79-94.

[30] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove.