Ernest and Aimée were only three days out at sea, en route to the Hawaiian Islands, when the “noise created by crashing steel,” frightened the passengers of the Sonoma. The upper-head of the ship’s high-pressure cylinder had burst inside the engine room, forcing the steamer to continue the Honolulu using only her starboard engine.[1] (The ship was saved by the efforts of Chief Engineer Little, a man that Ernest met during the tail-end of the Crusade in 1897.)[2] Within two weeks, the Hargrove’s had experienced two calamities at sea. When they reached Honolulu on April on April 5, 1901, Ernest gave an interview to the Hawaiian Star:

I am going the colonies for the purpose of ascertaining the feeling there for or against centralization of government by the various British colonies. The work will have a wider scope however than that relating to the Pacific possessions for I have studied the condition sentiments of India, the West Indies, Canada the South African colonies and it will be possible to deal with the feeling of every British colony upon this question of local self-government. This imperialistic idea of government is not, I believe, practicable. The reason it has gained so much support is because nothing has been suggested in place of it. When it comes to representatives being required to travel thousands of miles to attend sessions of the central legislature or parliament the advocates of this system will find many weaknesses of the plan. It is not probable that a central ‘home government similar to that at Washington for instance, would be as well qualified to pass consistent and practical legislation for the details of governing these islands or some other portion of the nation was would legislatures of those sections. I am not In favor of the colonies leaving the Mother Country, but the bonds between them should be more elastic.[3]

After the necessary repairs, the Sonoma was back at sea. It was promised that the Sonoma would arrive in Sydney “not a minute behind schedule time,” however, on April 10, her low-pressure piston cracked, and once again, the Sonoma staggered into port. They arrived in Sydney on April 19 with a single engine—three weeks after leaving San Francisco.[4] Upon arrival in Australia, Ernest and Aimée made a quick trip to Christ Church, New Zealand, to visit Percy Hargrove, Ernest’s brother. Ernest used the opportunity to distribute his pro-Boer pamphlet, An American View of the South African Situation.[5] They returned to Australia on May 11, 1901, taking up residence at the American Hotel (Swanston Street, Melbourne.)[6] The date of their arrival coincided with the festivities surrounding the inauguration of Australia’s new Federal Parliament at the Royal Exhibition Building.[7]

Ernest continued distributing his pro-Boer pamphlets and delivering his lectures in different towns. According to Aimée, crowds of people would drive them out of town by throwing eggs and bricks at them. (The harassment did not seem to bother Ernest.) Aimée began to suffer from migraines and nausea. Having seen virtually every stage of Leoline Wright’s pregnancy during the Crusade, Ernest quickly recognized the symptoms of morning sickness. With the news of Aimée’s pregnancy, the Hargroves settled down in Melbourne.[8] Perhaps a night of celebration was in order, as Aimée further states: “We really did just a bit more [in Australia] than we did in other places.”[9] Given their mutual affinity for the Opera, one could imagine Aimée and Ernest attending the performance of Verdi’s Aida, which debuted in Australia at Melbourne’s Her Majesty’s Theatre during the first week of June 1901.[10]

Federation Celebrations, 1901.[11]

The drawn-out British campaign in South Africa continued to drag on. Paul Kruger, who knew the cause was lost, sent Boer raiding parties directly into the Cape Colony. It was hoped that a few victories might inspire an uprising in the Dutch-majority territories, and, perhaps, draw the British away from the front lines on the borders of the Boer Republics. On September 17, 1901, after a year of fighting, Boer raiders struck a devastating blow to a British cavalry squadron led by Churchill’s cousin, Captain Sanderman. The fires of war, now rekindled, renewed the optimism of the Boers.[12] Ernest’s pamphlets were getting under the skin of government. One New Zealand paper noted that far-reaching extent of pro-Boer ramifications, and the extent of their financial resources of the organization, were “exemplified in the fact that members of Parliament and others throughout New Zealand and Australia […] recently had forwarded to them pamphlets from America written in the interests of the Boer cause.”[13] In late September 1901 George Fisher, M.H.R. for the City of Wellington, even urged New Zealand’s Prime Minister, Richard Seddon, to address the matter.[14] An unease with An American View was present in Australia as well.[15] “There is being circulated broadcast […] gratuitously over Australasia […] which is a long tirade of condemnation of British policy,” The Capricornian stated. It added: “It has been said these manifestations of feeling are like oil in feeding the flame of war, and this seems very probable […] The renewal of the literary and political campaign at the opening of the winter season may tend to prolong the war.”[16]

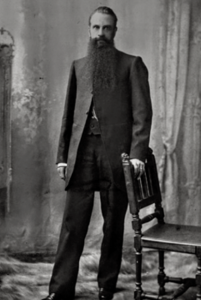

During this time, Ernest was drawn toward the local Spiritualist community. “[Ernest] has never cared very much for just ordinary people,” Aimée states, “he liked to exchange his ideas with people or express his own views.”[17] One such person was the “father of spiritualism in Australia,” Thomas Welton Stanford, brother of Leland Stanford, founder of Stanford University.

Clarendon Street 180, Stanford House.[18]

Welton, as he was known, was as tall as Ernest, and just as thin, but whereas Ernest had the face of a “pale ascetic,” Welton had piercing black eyes, and a dark, heavy beard. Though regarded as one of the foremost men of Australia, Welton’s interest with Spiritualism put him, “in a deplorable condition,” according to his family.[19] Welton’s large East Melbourne mansion was testament to his eclectic range of interests—complete with a domed observatory, gardens of rare plants, and aviaries of exotic birds. It was elegantly furnished with mahogany pieces from Europe, with one of the finest art collections in the country. He certainly had his own tastes. He did not “care for religious paintings,” yet considered Impressionism, (popular in Melbourne at the time,) as “the mark of the beast.” Stanford also possessed an envied collection of precious stones and metals from his adopted home, which were on display in the central entrance hall. There were other curios in Stanford’s collection that would have certainly fascinated Ernest. Beautiful leopard skins, a skull “plainly cast in Nature’s mould,” an aviary of peculiar birds, “plants of a rare kind” flourishing in the conservatory, cuneiform tablets, and a slate with a cryptic spirit-message. from his nephew, Leland Stanford Jr. The message, channeled through a spirit-medium, read: “My dear uncle I am pleased to meet you here this morning. I have long desired to come to you in this manner that it would remove the doubts that often crops up in your mind as to the absolute truth of spirit survival.”[20]

Thomas Welton Stanford.[21]

In 1852, Welton and the other Stanford brothers, left their Vermont homes in search of fortune in the California goldfields. By 1858, the Stanfords were operating one of the largest oil companies in the West. In 1859, Welton moved to Melbourne with his brother, De Witt, where they acquired the exclusive Australian marketing rights for Singer sewing machines. The brothers made a fortune, but De Witt died in 1862. Though unbearably lonely, his aversion to sea-travel prevented Welton from ever returning to America again. Welton amassed a considerable fortune from commercial endeavors, and subsequently vested his profits in real estate in and around Melbourne. This, too, was met with success, and Welton’s wealth multiplied. It seemed, briefly, that he would be equally successful in romance, when he met, fell deeply in love with, and married, a British woman named Minnie Watt. Minnie, unfortunately, would die in childbirth before they could celebrate their first anniversary. The shock and grief were so profound that “he was a changed man forever.”[22] Welton then gravitated toward the figures at the center of the Melbourne Spiritualist community, chief among them, his neighbor on Russell Street, the Theosophist, William H. Terry.[23] The Spiritualists claimed to have received a message from Welton’s dead wife, causing him to be drawn deeper into their circle, and he soon became a financial patron, and leader in his own right, and in 1870, Welton founded the Victorian Association of Progressive Spiritualists. Welton hosted fashionable séances in his home for many years, but, by the time Ernest and Aimée arrived, these meetings were conducted, almost exclusively, in his office on Russell Street.[24]

He was not the only Stanford to become interested in the Spiritualist movement. It was through a spirit message from their dead son, that Leland and Jane Stanford were inspired to found California’s Leland Stanford Jr. University. When young Leland Stanford Jr. died in Italy, in 1884, he appeared as a ghost to his father, Stanford Sr., who was holding a bedside vigil. “Father,” said the spirit, “I want you to build a university for the benefit of poor young men, so that they can have the same advantages the rich have.”[25] It was in this manner that the idea of founding Stanford University originated. Jane Stanford often told her husband, and several very close friends, that she frequently saw their dead son’ spirit, and could, “in her innermost soul and mind, believe that he was talking to her.” In 1891, when it was certain that the university would open, Jane and Leland secured David Starr Jordan as the president of their school. When Leland Sr. died in 1893, Jane became the sole trustee of Stanford University. It was said by those who knew her intimately, that her dead husband and son still appeared to her in spirit form.[26]

Welton, one of the original Board of Trustees for the University, was a financial patron of the institution, and watched, with pride, the growth of the school. The Thomas Welton Stanford Library, which opened on campus a year before Ernest and Aimée arrived, was built using the $300,000 donation from Welton who inherited the funds in the will of his late brother. This was a scheme worked out with Leland before his passing. (California legislation at the time stated that universities could only receive financial gifts during the lifetime of the donor.) Understandably, both Jordan and Welton were anxious about future donations, especially since Welton intended to donate his estate, and $6,000,000 fortune, to the university upon his death. The matter was solved, and by the end of 1901, Jane Stanford would execute, and deliver, to the university the final deeds of grant—the largest endowment to a university on record. Though Ernest was no longer a Board Member for the School For The Revival Of The Lost Mysteries Of Antiquity, it is easy to imagine both men discussing their experience with their respective California institutions.[27]

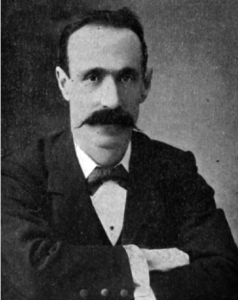

Charles Bailey.[28]

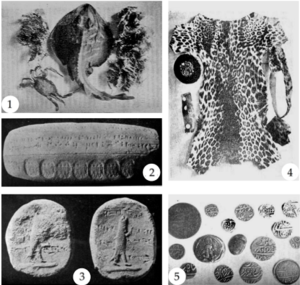

Welton had just recently become a patron of the renowned apport medium, Charles Bailey. In describing these fashionable séance’s, Aimée states: “The medium sits at one end and goes into a trance, and he brings things out of the ether and materializes them. [His specialty was] mainly sea waves and seaweed and live fishes.”[29]’[30]

Some of Bailey’s apports: 1. Fish, Crab, And Portion Of Seaweed. 2. Babylonian Book Cylinder (Kiln-Baked Clay.) 3. Cuneiform Tablets. 4. Leopard Skin Rug; Indian Cap; Bedouin Arab Woman’s Head Dress And Witch Doctor’s Belt. 5. Old Indian Coins In Silver; One In Bronze. Ancient Persian Silver Coin; Modern Cairo Coin. Egyptian Scarabaeus[31]

By November, Dr. James Martin Peebles, the renowned Spiritualist, arrived in Melbourne. He had accepted an invitation from the Victorian Association of Spiritualists to lecture in Melbourne for a few months.[32] His talks at the time focused on the notion of the “Living Christ” understood by Dr. Peebles as “a spiritually exalted state in this present life…the living Christ within.”[33] The term had gained traction within the esoteric community after Paul Tyner’s 1897 work, The Living Christ: An Exposition Of The Immortality Of Man In Soul And Body.[34] “Churchianic religion talks of a dead Jesus,” Dr. Peebles stated. “The horn that yellowed in Kedron will not suffice for this century; neither will the leathern girdles nor wild locusts of any wilderness Baptist. Blessed be Spiritualism, with its presence of the Living Christ.”[35] Peebles claimed that he received his Theosophical diploma “direct from the loyal head, Adyar, India.” In actuality, he joined the Society in San Diego, on Halloween, 1894.[36] Though Ernest and Pebbles had different opinions regarding Olcott, they could both agree that Tingley was operating under “false colors.”[37] Peebles would have told Ernest stories of his time with Judge, Blavatsky, and Olcott at the Lamasery. Perhaps, given the recent performance of Aida, Peebles told of his very first encounter with Blavatsky in Cairo, in 1872, when Aida made debuted.[38] In December 1901, in anticipation of their child, Ernest and Aimée returned to Europe, and settled in Brussels before the end of the year.[39] It is unclear when the Hargroves left Australia. We know that Bailey first made his appearance with Welton around November 1901. Leyds’s payroll in late 1901 lists Ernest’s address as Brussels. We might assume the couple returned to Europe sometime in December 1901, in anticipation of their child.[40]

Dr. James Martin Peebles.[41]

While the Hargroves were preparing their departure for Europe, Hargrove’s uncle, John Aird (along with the artist Alma Tadema, and Winston Churchill) was en route from London to Egypt to attend the opening of the Assouan Dam by the Duke of Connaught.[42] During the construction Aird discovered an (alleged) six-thousand-year-old necklace; a necklace whose former owner appeared to Marie Corelli as an apparition.[43]

HARGROVE

I. “Refined English Atmosphere.”

II. “The Purple Mother.”

III. “Kitty Tingley, Despot.”

IV. “Villa Maria.”

V. “Dr. Leyds And The Occultation Of World Politics.”

VI. “The South African Situation.”

VII. “The Conciliator Of South Africa.”

VIII. “Transvaal Vs. Churchill.”

IX. “The Séances Of Thomas Welton Stanford.”

X. “The White Stag.”

XI. “The Hair Line Of Duty.”

SOURCES:

[1] “Engineer Little Of The Ventura Praised.” The Pacific Commercial Advertiser: Honolulu. (Honolulu, Hawaii) April 6, 1901; “Along the Wharf.” The Honolulu Republican. (Honolulu, Hawaii) April 6, 1901.

[2] “At about this time of birth [of Claude and Leoline Wright’s baby] a canary that for several trips had been the pet of Chief Engineer Little died, and the sailors of the steamer, who knew little of the science of Theosophy beyond a faint idea of the doctrine of the reincarnation of the soul, consoled the officer on the loss of his bird by telling him that its spirit had passed to the new passenger.” [“An Infant Joins The Occult Crusade.” The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, California) February 16, 1897.]

[3] “Favors Self Government.” The Hawaii Star. (Honolulu, [Oahu]) April 6, 1901.

[4] “The Sonoma At Auckland.” The Sydney Herald. (Sydney, Australia) April 19, 1901.

[5] By late September 1901, Ernest’s efforts in New Zealand would prove a success. The Press would write: “The far-reaching extent of pro-Boer ramifications, and the extent of the financial resources of the organization are exemplified in the fact that members of Parliament and others throughout New Zealand and Australia have recently had forwarded to them pamphlets from America written in the interests of the Boer cause.” George Fisher, M.H.R. for the City of Wellington, told New Zealand’s Prime Minister, Richard Seddon: “One of these pamphlets has just been brought under my notice. It is entitled, An American View of the South African Situation: How Australia Might Help Great Britain, by ‘T.,’ author of World Politics, etc. It is dated New York, 1901, but has no printer’s imprint upon it. The pamphlet of some sixty-five pages, which is well written, urges the New Zealand and Commonwealth Parliaments to ask for a reversal of the present policy in South Africa. ‘This,’ adds the writer, ‘would do more than any other thing to change public opinion in Great Britain to save South Africa for the Empire, and to save the Empire for the world.’” see “Pro-Boer Pamphlets Circulated In New Zealand” The Press. (Christ Church, New Zealand) October 9, 1901; New Zealand, Legislative Council And House Of Representatives, “Parliamentary Debates.” Parliamentary Debates, CXIX, John Mackay, Government Printer. Wellington, New Zealand. (1901): 312–315.

[6] Reports Of vessels arrived (or Shipping reports.) Series 1291, Reels 1263-1285, 2851. State Records Authority of New South Wales. Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia; “Metropolitan Licensing Court.” The Age. (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.) August 8, 1901; E.T. Hargrove entry; S.S. Ventura Passenger Manifest, May 11, 1901, New South Wales Government.; Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove.

[7] “Opening Of The First Parliament: Celebrations Throughout The Country.” Parliament Of Australia Exhibitions—For Peace, Order, And Good Government: The First Parliament Of The Commonwealth Of Australia.

[8] Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove.

[9] Ibid.

[10] “Verdi’s Aida.” The Age. (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) June 3, 1901.

[11] Stereograph-Glass, Irish National Foresters Society Banner, Federation Celebrations, 1901. Source: Museums Victoria.

[12] Pakenham, Thomas. The Boer War. Avon Books. New York, New York. (1979): 551, 555-565.

[13] “Pro-Boer Pamphlets Circulated In New Zealand.” The Press. (Christ Church, New Zealand) October 9, 1901.

[14] New Zealand, Legislative Council And House Of Representatives, “Parliamentary Debates.” Parliamentary Debates, CXIX, John Mackay, Government Printer. Wellington, New Zealand. (1901): 312–315.

[15] “Friday, 6th December 1901.” The Ballarat Star. (Victoria, Australia) December 6, 1901.

[16] “Conditions Of Peace.” The Capricornian. (Rockhampton, Queensland.) November 16, 1901.

[17] Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove.

[18] “East Melbourne, Clarendon Street 180, Stanford House.” East Melbourne Historical Society. Accessed July 20, 2021. https://emhs.org.au/history/buildings/east_melbourne_clarendon_street_180_stanford_house.

[19] Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove; Berner, Bertha. Mrs. Leland Stanford: An Intimate Account. Stanford University Press. Redwood City, California. (1935): 165; Berner, Bertha. Incidents In The Life Of Mrs. Leland Stanford. Edward Brothers Inc. Ann Arbor, Michigan. (1934): 146-147.

[20] Lenker, Lisa M. Haunted Culture And Surrogate Space: A New Historicist Account Of Nineteenth-Century American Spiritualism. Stanford University Press, Redwood City, California. (1998): 286.

[21] Stanford, Thomas Welton, 1832-1918. (1898) SC1071. Box: 3, Folder: Stanford, Thomas Welton. Stanford Family Photographs. Stanford University. Libraries. Department of Special Collections and University Archives. Palo Alto, California.

[22] “T.W.S. Of Spook Fame.” The Stanford Daily (Palo Alto, California) October 31, 1930; Berner, Bertha. Incidents In The Life Of Mrs. Leland Stanford. Edward Brothers Inc. Ann Arbor, Michigan. (1934): 146-147.

[23] William Henry Terry was an occult bookstore proprietor, and founder-editor of Melbourne’s Spiritualist magazine, The Harbinger of Light. Terry, in addition to his spiritualist involvement, was an inaugural member, and Councillor, of the Adyar-based Theosophical Society in Australia. He also held the distinction of being the recipient of a letter from Master Morya. [Jinarajadasa, C. Letters From The Masters Of The Wisdom. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Chennai, India. (1925): 152-153; Neff, Mary K. “Letter from Miss Neff,” The American Theosophist Vol. XXXI, No. 2 (February 1943): 40; Eck, Sven. Damodar And The Pioneers Of The Theosophical Movement. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Chennai, India. (1965): 164; George E. Linton and Virginia Hanson, (eds.) Readers Guide to The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, Chennai, India. (1972): 244.]

[24] Potts, Daniel E. “Stanford, Thomas Welton (1832–1918.)” Australian Dictionary Of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/stanford-thomas-welton-8620/text15059, published first in hardcopy 1990, accessed online 7 February 2020; Viva. “Melbourne Notes.” The Sydney Mail And New South Wales Advertiser. (Sydney, Australia) October 19, 1901; “The Medium Bailey.” Light. Vol. XXV, No. 1,302. (December 23, 1905): 609; Osborne, Carol Margot; Paul Venable Turner, and Anita Ventura Mozley. Museum Builders in the West: The Stanfords As Collectors and Patrons of Art, 1870-1906. Stanford University Museum of Art, Stanford University. (1986): 72.

[25] “Leland Stanford’s Vision.” The Essex County Herald. (Guildhall, Vermont) March 10, 1905.

[26] “Aged Mrs. Stanford Feared Death From Poison After Recent Attempt Here Against Her Life.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) March 2, 1905; Wolfe, Susan. “Who Killed Jane Stanford?” Stanford Magazine. (September/October 2003) Online. https://stanfordmag.org/contents/who-killed-jane-stanford.

[27] “Stanford Asks Berkley’s Aid.” The San Francisco Chronicle. (San Francisco, California) October 13, 1900; “Monuments Of Art At Stanford University.” The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco, California) October 13, 1901; “Largest Endowment To University On Record.” The Evening Sentinel. (Santa Cruz, California) December 16, 1901; “President’s Report.” Annual Report Of The President Of Stanford University For The Twenty-Seventh Academic Years Ending August 31, 1918. Leland Stanford Junior University Publications. No. 33 (1918): 5-23.

[28] X. Rigid Tests Of The Occult. J.C. Stephens, Printer. Melbourne, Australia. (1904): Front-plate.

[29] Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove.

[30] Though Stanford would not sponsor this medium until 1902, there is little doubt that the person of whom Aimée is referring, was the apport medium, Charles Bailey. Stanford, in the years following, would host eighty seances with Bailey. In H.J. Irwin’s biography of Bailey for The Journal Of The Society For Psychical Research, he states: “Stanford had several large aviaries in his home and his interest in birds seemingly instigated an obliging change in the nature of apports from mundane objects like stones to more appealing ones such as birds, nests, and eggs. Among other apports were live fish, large quantities of seaweed and sand replete with aquatic fauna, a fishing net, a live turtle.” [Irwin, H. J. “Charles Bailey: A Biographical Study of the Australian Apport Medium.” The Journal Of The Society For Psychical Research Vol. 54, No. 807.]

[31] 1. Fish, Crab, And Portion Of Seaweed. 2. Babylonian Book Cylinder (Kiln-Baked Clay.) 3. Cuneiform Tablets. 4. Leopard Skin Rug; Indian Cap; Bedouin Arab Woman’s Head Dress And Witch Doctor’s Belt. 5. Old Indian Coins In Silver; One In Bronze. Ancient Persian Silver Coin; Modern Cairo Coin. Egyptian Scarabaeus. [X. Rigid Tests Of The Occult. J.C. Stephens, Printer. Melbourne, Australia. (1904): 24, 87, 92, 118, 128.]

[32] “About People.” The Age. (Melbourne, Australia) September 25, 1901; Whipple, Edward. A Biography of James M. Peebles, M.D., A.M. Self-Published. Battle Creek, Michigan. (1901) 585.

[33] “Now And Again.” Fitzroy City Press. (Victoria, Australia) November 8, 1901; “Church And Organ.” Punch. (Melbourne, Australia) November 14, 1901.

[34] Tyner, Paul. The Living Christ: An Exposition Of The Immortality Of Man In Soul And Body. The Temple Publishing Company. Denver, Colorado. (1897.)

[35] “Has Spiritualism Had Its Day?” The Literary Digest. Vol. XXIII. No. 19. (November 9, 1901): 572.

[36] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 11864. (website file: 1D: 1894-1897) James M. Peebles, M.D.

[37] Whipple, Edward. A Biography of James M. Peebles, M.D., A.M. Self-Published. Battle Creek, Michigan (1901) 529-531.

[38] Peebles, J.M. Round the World; Or Travels In Polynesia, China, India, Arabia, Egypt, Syria, And Other “Heathen” Countries. Colby And Rich, Publishers. Boston, Massachusetts. (1875): 315; Peebles, J.M. “Round The World Among Spiritualists.” The Spiritualist Newspaper. Vol. VI, No. 6. (February 5, 1875): 61-77; Higgins, Shawn. “From The Seventh Arrondissement To The Seventh Ward: Blavatsky’s Arrival in America 1873.” Theosophical History. Vol. XIX No. 4. (October 2018): 158-171.

[39] It is unclear when the Hargrove’s left Australia. We know that Bailey first made his appearance with Welton around November 1901. Leyds’ payroll in late 1901 lists Ernest’s address as Brussels. We might assume the couple returned to Europe sometime in December 1901 in anticipation of their child. [Davey, Arthur. The British Pro-Boers 1877-1902. Tafelberg Publishers. Cape Town, South Africa. (1978): 120.]

[40] Davey, Arthur. The British Pro-Boers 1877-1902. Tafelberg Publishers. Cape Town, South Africa. (1978): 120.

[41] Peebles, James Martin. The Spirit’s Pathway Traced: Did it Pre-exist, and Does it Reincarnate Again Into Mortal Life? Dr. Peebles Health Institute. Battle Creek, Michigan. (1906): 1.

[42] “Our London Correspondence.” The Guardian. (London, England) November 19, 1902; “The Nile Barrage.” The Guardian. (London, England) December 10, 1902.

[43] Vyer, Bertha. Memoirs Of Marie Corelli. Alston Rivers Ltd. London, England. (1930): 186.