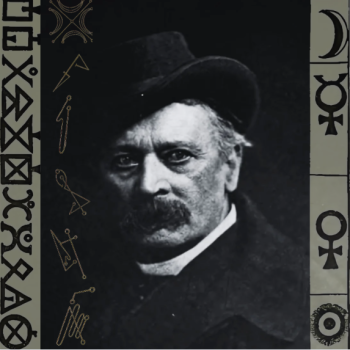

Ernest Temple Hargrove.[1]

Ernest Temple Hargrove was born on December 17, 1870, at Laurel Lodge, Twickenham, in West London, to James Sydney Hargrove and Jessie (née Aird) Hargrove. He would have been the couple’s fifth child, however, two weeks before Ernest was born, on December 3, 1870, his 18-month-old-sister, also named Jessie, died in the family home. Ernest would be the fourth oldest of eight Hargrove children; ranking from oldest to youngest, they were: Constance, Norah, Sidney, Ernest, Percy, Herbert, Reginald, and Hilda. By all accounts, the family were close, and the home life was happy, with a “refined English atmosphere.”[2]

Ernest’s paternal line included a great grandfather, Ely Hargrove, the writer of “Anecdotes Of Archery From The Earliest Ages To The Year 1791,” which provided a historical survey of Robin Hood, and grandfather, William Hargrove, who wrote “History And Description Of The Ancient City Of York.”[3] His father, J.S. Hargrove, was the family solicitor of John Horatio Lloyd, grandfather of Constance Lloyd, future-wife of Oscar Wilde. J.S. Hargrove “A gentleman in every sense of the word, clever with a cheery, amiable manner and whose friendship everyone appreciated,” and one of the directors of the Carl Rosa Opera Company.[4] Wilde himself would later write that it was for Lloyd that the Hargrove family owed much of their own “considerable wealth.”[5] Shortly before his marriage to Constance, J.S. Hargrove interviewed Wilde in his home, as Otho Lloyd, Constance’s nephew would later recall: “[Wilde] had an interview in chambers with Mr. Hargrove, the family lawyer, and, pressed as to his ability to pay, replied: ‘I could hold out no promise, but I could write you a sonnet if you think that that would be of any help.’”[6] In his later years, Ernest would record his impressions of Wilde:

Many years ago I met him. I was very young, and what struck me about him chiefly was his bulk and his supercilious manner. Older men who had talked of him in my presence had admitted that he had genius, but they had ridiculed his eccentricity. I was confused but was too young in any case to judge for myself.[7]

Ernest’s mother, Jessie Aird, was the daughter of John Aird—a distinguished engineer whose projects included the Crystal Palace, and the Royal Albert Hall.[8] John Aird, Jr., Jessie’s brother, and Ernest’s uncle, was the M.P. of Paddington North. It was said that he “took his [political cues] from his friend and political godfather, Lord Randolph Churchill,” the M.P. of Paddington South; a family friend, neighbor, and father of Winston Churchill.[9] In addition to Aird’s feats of civil engineering, he was also a patron of the arts and Master Mason—being the first Master of London’s Evening Star Lodge.[10]

(Laurel Lodge c. 1875)[11]

Ernest was baptized in the Church of England’s Holy Trinity Church, in Twickenham, on March 19, 1871, by the non-conformist vicar, Isaac Taylor.[12] The Hargrove’s would have certainly been aware of their Vicar’s unorthodox beliefs.[13] As Ernest would later say, his family belonged to the Church of England, but he “couldn’t…believe in Hell and similar accepted theories of the creed.”[14]

Ernest received his education in various preparatory schools, including the prestigious Harrow School, where he admittedly “spent most of his time reading novels.” Upon leaving Harrow in 1886, Ernest, who had studied for the Diplomatic Service, was then offered the opportunity to attend Cambridge University or travel abroad. Choosing the latter, the eighteen-year-old Ernest toured Australasia, and Ceylon, before returning to London in the early 1890s.[15] It was in the summer of 1891, while on holiday in an English seaside resort, when Hargrove was first introduced to Theosophy, and subsequently had a powerful conversion experience.[16]

He became a student of William Quan Judge, the leader of the American Section. In truth he was something like a second father. In 1894 he toured America as a Theosophical lecturer. But events transpired which lead to the American Section declaring autonomy in 1895. These events began in 1895 in the home of his friends, Clem and Genevieve Griscom. Their home “became one of the most real and vital centers of the whole Theosophical movement.” It was W.Q. Judge’s habit to take Sunday dinner at the Griscom home, and to spend the evening there as their guest—“often he would stay for weeks at a time, going into the city with Mr. Griscom in the morning, but returning again in the afternoon.” At the time there was infighting among the leaders of the international representatives of the Theosophical Society. Over the winter of 1894-95 Clem was in communication with members of the Society sympathetic towards Judge, and it was at the Griscom house that the plans for succession and autonomy were drafted for the Convention of the American Section in the spring of 1895.[17] Shortly after the American Section split, Hargrove followed suit, and helped lead a group of English Theosophists who supported Judge. Later that summer Hargrove would make a second lecture tour of America.

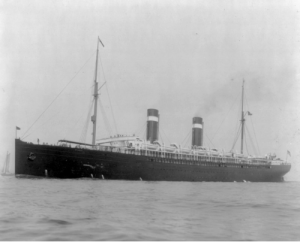

S.S. St. Louis.

Hargrove purchased a ticket on the S.S. St. Louis, and would, along with C.A. Griscom Sr., depart from Southampton to New York on August 26.[18] The elder Griscom was in England for the debut launch of the St. Louis, his new ship. Present at the launch were Griscom’s friends, Prince Edward, and John Aird (Hargrove’s uncle,) the man who built the dock.[19] In 1895 the Red Star Line made significant changes in its European terminus when it moved from Liverpool to Southampton. This change of location (from Mersey to the English Channel,) placed the company in direct competition with the Hamburg-American and Norddeutscher Lloyd Lines, but diminished direct competition with larger competitors, the Cunard, and White Star Lines. This was a deliberate plan carried out by C.A. Griscom Sr., the owner of the Red Star Line, and the latter two rivals. In exchange for these yieldings, White Star and Cunard paid Griscom $30,000 a year, collectively, to cover the costs relocating to Southampton.[20] (In 1902 J.P. Morgan and Griscom would establish the International Mercantile Marine, and effectively create a shipping monopoly under which their former British competitors would be absorbed.)[21]

The Hargrove home (25 Lancaster Gate) was filled with the usual excitement that came with travel preparations. The steamer-chests were packed (and re-packed) with anxious expectations. Both Hargrove and his father, James Sydney, were about to embark on trips in the interest of the respective fields. For Hargrove it was Theosophy; for James Sydney it was in the interest of his clients, the Lloyd family, for, as the London papers reported, Oscar Wilde’s imprisonment had caused him bankruptcy.[22] Wilde’s fall from grace was almost total—almost. James Sydney received a prison-letter from Wilde around this time that was meant to be forwarded to the author’s wife, Constance Lloyd. James was pleasantly surprised when he discovered that Wilde’s letter was both sentimental and sincere. “One of the most touching […] letters that had ever come under my eye,” James Sydney said.[23]

Ernest arrived in New York in the summer of 1895, but little did he know that Judge would die the following winter. he himself would become President of the American Section, leading a Theosophical “missionary crusade” around the world with a little-known Theosophist around the world. She claimed to have been a secret esoteric leader, nominated personally by Judge, but he now had serious doubts. It was the spring of 1897, the Theosophists had purchased a compound out in Point Loma, California, and he was seriously contemplating resigning. He was also in love with Aimée, the daughter of Tingley’s loyal lieutenant. The nature of that relationship was suspicious as well.

HARGROVE

I. “Refined English Atmosphere.”

II. “The Purple Mother.”

III. “Kitty Tingley, Despot.”

IV. “Villa Maria.”

V. “Dr. Leyds And The Occultation Of World Politics.”

VI. “The South African Situation.”

VII. “The Conciliator Of South Africa.”

VIII. “Transvaal Vs. Churchill.”

IX. “The Séances Of Thomas Welton Stanford.”

X. “The White Stag.”

XI. “The Hair Line Of Duty.”

SOURCES:

[1] Bennett, John E. “Theosophy In America.” The National Magazine. Vol. VI, No. 5 (August 1897): 403-411.

[2] “Deaths.” The London Daily News (London, England) December 6, 1870. [“Births, Marriages, and Deaths.” London Observer, December 25, 1870. England & Wales, Civil Registration Birth Index, 1837-1915. Registration Year: 1871. Registration Quarter: Jan-Feb-March. Registration District: Brentford. Volume 3A. Page: 63. [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA.]

1881 England Census. Class: RG11; Piece: 656; Folio: 104; Page: 17; GSU roll: 1341152.

Kate Swan, “Preaching Theosophy to Socialists,” The New York World (New York, New York) May 10, 1896.

[3] Hargrove, Ely. Anecdotes Of Archery From The Earliest Ages To The Year 1791. E. Hargrove Knaresbro. York, England (1792); Hargrove, William. History And Description Of The Ancient City Of York. William Alexander. England (1818.)

[4] “Funeral Of Mr. Carl Rosa” The Morning Post (London, England) May 7, 1889; “The Funeral Of Mr. Carl Rosa” The Era (London, England) May 11, 1889; Aird, Charles. Depford, Toronto and Kingston: The Early Years of Charles Aird, Victorian Engineer. The Grimsay Press. Glasgow, Scotland. (2005): 332-333.

[5] Oscar Wilde to More Adey. April 7, 1897. In The Letters of Oscar Wilde. London, UK: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1962. 524-28.

[6] Otho Lloyd to Mr. Symonds. [MS. WILDE BX 32 FLD 20 Lloyd 1937 May 27]

[7] H. “Reviews: De Profundis, or the Breaking and Making of a Man.” Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. III, No. 2. (October 1905): 332-225.

[8] “Sir John Aird, Bart., M.P.” The Strand. Vol. XXX, No. 178 (November 1905): 453-455.

[9] “Great Engineer Was Sir J. Aird.” The Province. (Vancouver, British Columbia), February 11, 1911.

[10] Boyles, J.F. “The Private Art Collections of London.” The Art Journal Vol. 53 (1891):135-140.

“The Evening Star Lodge, No. 1719” The Freemason’s Chronicle. Vol. XIII, No. 327. (April 2, 1881): 229.

“Quarterly Communications Of The United Grand Lodge” The Freemason’s Chronicle. Vol. XXXIII, No. 843. (March 7, 1891): 152-155.

[11] “Houses Of Local Interest And Their Occupiers: Laurel Lodge.” The Twickenham Museum . Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.twickenham-museum.org.uk/house-details.php?houseid=81&categoryid=1.

[12] London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Board of Guardian Records, 1834-1906/Church of England Parish Registers, 1754-1906; Reference Number: dro/150/002.

[13] Isaac Taylor was Vicar of the Church of England’s Holy Trinity Church. While an incumbent in Holy Trinity in 1869, Taylor used his leisure time to write Etruscan Researches (1874) in which he contended the Ugrian origins of the Etruscan language. In 1875 Taylor began researching the origin of the alphabet. In Greeks and Goths: a Study on the Runes (1879,) Taylor argued that German runes were of Greek origin, which produced contention during his day. In 1883 he published The Alphabet, an Account of the Origin and Development of Letters in which he endeavored to prove that alphabetical changes were the product of evolution occurring in accordance with fixed laws, stating: “Epigraphy and paleography may claim, no less than philology or biology, to be ranked among the inductive sciences.” [The Encyclopedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. 11th ed. Vol. XXVI. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, England. (1911): 469.] His paper on the Origin of the Aryans delivered at the British Association (1887,) and later developed into a book, notes that by the end of the 19th century, the racial characteristics of white skin, blonde hair, and blue eyes, were associated with the “Aryans.” Taylor writes: “The evidence of language shows that the primitive Aryans must have inhabited forest clad country in the neighborhood of the sea, covered during prolonged winter with snow. It has also been urged that the primitive Aryan type was that of the Scandinavian and North German peoples—dolichocephalic, tall, with white skin, fair hair, and blue eyes, and that those darker and shorter races of Eastern and Southern Europe who speak Aryan languages are mainly of Iberian or Turanian blood, having acquired their Aryan speech from Aryan conquerors.” [“The Aryans.” John Bull. (London, England) October 1, 1887.]

[14] Swan, Kate. “Preaching Theosophy to Socialists.” The New York World. (New York, New York) May 10, 1896.

[15] Welch, R. Courtenay. The Harrow School Register, 1801-1893. Longmans, Green, and Co. London, England. (1894): 567. (Hargrove studied under Assistant-Master, Charles Colbeck.)

[16] “Faces Of Friends: Ernest Temple Hargrove.“ The Path. Vol. IX, No. 6 (September 1894): 182-184; Kate Swan, “Preaching Theosophy to Socialists.” The New York World. (New York, New York) May 10, 1896.

[17] “Prominent Long Islanders.” The Times-Union (Brooklyn, New York) July 2, 1897; Mitchell, Henry Bedinger. “A Stone of the Foundation.” The Theosophical Quarterly. XVII, No. 1 (July 1919): 9-21.

[18] “Proud Of Her Record.” New York Tribune. (New York, New York) September 1, 1895.

[19] “Death Claims C.A. Griscom; Noted Financier.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) November 12, 1912.

[20] “The New Graving Dock at Southampton.” Herapath’s Railway Journal. Vol. LVII, No. 2934 (August 9, 1895): 803-04; “Royal Visit To Southampton.” The Times. (London, England.) August 5, 1895; “Opening Of The New Graving Dock At Southampton.” The Hampshire Advertiser (Hampshire, England.) August 7, 1895; Middlemas, Robert Keith. The Master Builders. Hutchinson. London, England. (1963) 121-59; Flayhart, William H. The American Line: 1871-1902. Norton. New York, New York. (2000): 138-139.

[21] “The Ship Trust That Has Drawn Uncle Sam’s Fire.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) June 23, 1912.

[22] “Bankruptcy Of Oscar Wilde.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) August 22, 1895.

[23] Appendix C: A Visit from Mr. Hargrove. (1962). In Rupert Hart-Davis (Ed.), The Letters Of Oscar Wilde (pp. 871-872). New York, New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.