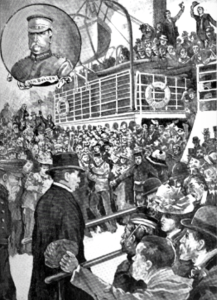

General Sir Redvers Buller And Staff Going On Board Dunottar Castle, October 14, 1899.[1]

Ernest and Aimée returned to England where they would leave Southampton for the Cape Colony on the R.M.S. Dunnottar Castle, the same vessel as Sir Redvers Buller, the British Commander-in-Chief of the Boer War. A large, raucous crowd of people thronged the platforms at Waterloo Station, to see the Redvers Buller, and the British army, packed into the trains leaving for the Southampton Dock. It was easy enough to understand their enthusiasm. The night before, Ernest saw a placard which read “Boer Outrages on Women” in huge type. Ernest states:

No one can believe more profoundly than I do in my own people. No one can believe more sincerely that when they entered upon that South African war, they entered upon it conscientiously believing that they were doing the right thing, believing that there was no other way out of it, and I am convinced that whatever this country has done, has been done by the mass of the people with the same conscientiousness, with the same belief that it was the only solution of the trouble which confronted them at that moment. There is no earthly question in my mind about that. Unfortunately, so far as our war is concerned, I happen to know that we were misled; that the English people were deceived—a hopeless lie. Nothing in it at all, but it was done in order to keep the war fever up at boiling point.[2]

Ernest wanted to defend Chamberlain; he did not believe that he was “the scoundrel that some people would paint him to be.” From Ernest’s point of view:

Chamberlain was a conscientious disciple of Machiavelli—conscientious, sincere, believing as genuinely as we believe in our particular belief, whatever it may be, that the end justifies the means.” Manipulating the press to influence the public was just another example.[3]

On October 14, 1899, the Dunottar Castle set sail. The decks remained crowded with the passengers who looked back towards the fading shores, wondering if they would come home again; then everyone rushed to their cabin to arrange their luggage, and prepare themselves to the long voyage. “The British War Office thinking it probable that the Boers would be wiped out and that the war would be over, before [Buller] arrived,” thought Ernest. The War Office had an Intelligence Branch that prepared two volumes on the military and other resources of the Boer Republics, and had advised the War Office that 200,000 men would be required. “When these two volumes were sent to Buller before his departure,” Ernest recalled, “[Buller] returned them within an hour, with the message that he ‘knew all about South Africa.’” It was impossible to teach Buller anything, thought Ernest. “He was not what is ordinarily called a vain man, but thought he knew it all, or, rather, that he knew as much as was necessary, and certainly ten times as much as any civilian.”[4]

“Buller Arrives.”

There was a fancy dress ball which divided the opinions of passengers—some argued that such balls were “healthy and amusing.” Others found them “exceedingly tiresome.” Aimée was of the former opinion, but it mattered little. “They suspected us on the boat, and we kept very much to ourselves on the account,” Aimée would state. A look at the passenger manifest for the Dunnottar Castle tells us why.[5] On board the Dunnottar Castle, in a room not far from his own, was Ernest’s London neighbor (and family friend,) a war correspondent for the Morning Post named Winston Churchill.[6] (A full account of the trip can be found in Churchill’s London To Ladysmith Via Pretoria and A Roving Commission: My Early Life.)[7] The long-drawn voyage came to an ended on October 30, 1899. It was an auspicious day for Ernest, it being the eighth anniversary of his joining the Theosophical Society.[8] The Dunnottar Castle passed Robben Island, populated with poisonous serpents, wild dogs and lepers undergoing quarantine. In darkness they entered Table Bay, where a military party greeted them on the quay. On the fog covered the sea, the rain-drenched soldiers waited “patiently impatient,” for the signaling station to grant them entry. At the dock, a man came on board with a newspaper, and the soldiers harassed him “as though he had been a dangerous criminal,” and soon the paper was taken from him by a soldier who, under an electric lamp, read extracts. The audience listened solemnly as they learned the fate “of their brothers, uncles, cousins in the list of casualties.”[9]

Mount Nelson Hotel.[10]

In Cape Town, Ernest and Aimée checked into the Mount Nelson Hotel, the “Metropole” of South Africa—or the “Helots’ Rest” as Milner called it. The hotel, with its collection of old prints, Chippendale chairs, and Persian rugs, would be the home of Aimée and Ernest for ensuing eight months.[11]

Churchill In Prison.)[12]

On November 15, 1899, Churchill was captured and imprisoned by the Boers.[13] The newspapers said: “When the engine steamed off Mr. Churchill remained behind to help. Everyone will hope that he is not killed. If he is a prisoner in the hands of the Boers, Lord Randolph Churchill’s son will be as much honored as among his own people.”[14]

Ernest had long grown disheartened by the press, and though he certainly felt uneasy about Churchill being captured, there was no way to know whether any of these events had even transpired. He had personally witnessed “certain news correspondents” who approached the British military censor at Cape Town, and asked permission to telegraph home that the Boers were desecrating churches. When the officer expressed his surprise, and told the correspondents that he was unaware of such news, their nonchalant answer was simply: “Oh, well news must be sent home that will keep up the war spirit.” The false news was not sent by cable, rather it was sent by mail, “and did its evil work in English papers.” [15]

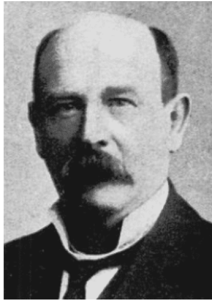

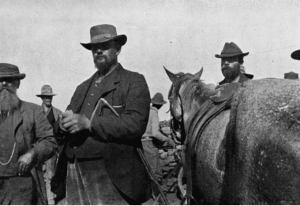

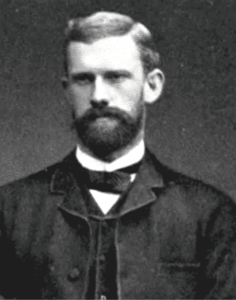

Ernest had learned not to trust the newspapers from his experience leading the Theosophical Society.[16] So instead, he decided to establish a newspaper of his own. He met Sam Marks, owner of Hatherly Distillery, and asked if he would be interested in financing the endeavor, however nothing developed from that meeting.[17] Perhaps it was in the interest of creating a paper that Ernest was introduced to Jacobus Wilhelmus Sauer at a dinner party in Cape Town in late November. Sauer, the owner of The South African News, was a prominent liberal politician who was the Commissioner of Public Works.[18] The men became fast friends, and Sauer insisted that Ernest should accompany him on “the treacherous mission as an official member” to a meeting with “Pony” De Wett (a Free State commandant, and brother of Commandant Christian De Wet) on November 23, 1899. Sauer addressed the meeting in a forty minute speech, and while admitting that “blood is thicker than water,” counseled abstention from rebellion (as England must win in the end.) Another deputation was arranged to proceed to Barkly East to urge the Boer General, Jan Hendrik Olivier, not to come to Dordrecht. Another meeting was held (also addressed by Sauer) on November 27, and a second waited upon Olivier. A letter that was later intercepted by the British, revealed that the deputation was a ruse. Olivier stated: “Today (November 28) already I received the second deputation from Dordrecht not to come to Dordrecht. This is asked officially, but privately they say that this is also a blind, and that we must come once.” On December 2, 1899, Olivier was received with open arms at Dordrecht. Rebellion in that district immediately followed.[19]

Wilhelmus Sauer.

(Right) General Peter “Pony” De Wet.[20]

Though he did not possess the necessary letters of introduction to enter into the Boer republics, Ernest, nevertheless, traveled to Lourenço Marques to seek admittance with the Transvaal consul. The consulate tried to deter him from going, stating that he might have to remain in Transvaal until the end of the war.[21] He arrived at Pretoria on January 17, 1900, and though he was “quite unacquainted with Dutch,” he was pleasantly surprised to find that most everyone spoke English. He was also pleased to discover that, “although he [was] distinctly English in appearance and manner,” he could walk around the streets of Pretoria “as freely, and with as little interference as about the streets of London.”[22]

Transvaal Hotel.[23]

At the Transvaal Hotel, where Ernest was staying, he met another one of Leyd’s agents, the Irish-Australian journalist, Arthur Lynch. “I came here with [a] mission from Dr Leyds to observe any facts—such as the employment of natives by the English—which it would be useful to make known in Europe with a view to influencing public opinion,” Lynch wrote in a correspondence two days before Ernest arrived.[24] Ernest also met several Frenchmen at the hotel, who had witnessed the aftermath of the recent battle of Colenso. They admitted to Ernest that it was “useless to send the accounts of the losses to the French journals, became nobody would believe them.” Following the battle of Colenso (December 15, 1899,) despite the Boer trenches having been shelled for days, they only lost seven men. The Boers were, astonishingly, holding their own against the British Empire. Ernest also heard rumors to the effect that Churchill, a prisoner of the Boers, had escaped from prison—some people claimed that he broke his parole, while others said that the Transvaal Executive had purposely allowed him to escape. (The myth-making of the escape was deliberate. “The British nation was smarting under a series of military reverses,” Churchill would later state, “…the news of my outwitting the Boers was received with enormous and no doubt disproportionate satisfaction.”)[25]

On January 20, 1900 Ernest met with President Kruger, he said, with a message from Sauer and Merriman stating that they were prepared to openly declare their support for the Boer Republics and to distribute propaganda in the Cape Colony, “provided an official declaration is given that the Republics only desire to secure complete independence.” Ernest wanted Kruger to write a letter directly to Queen Victoria, but Kruger refused and “thought it desirable that [he] should write a letter to [Ernest’ personally, in which an answer is given to [Ernest’s] question.” Ernest thought “that a great propaganda” could be made in the Cape Colony, “whereby influence can be brought to bear again on the English people and the world.” Kruger was skeptical, but reasoned that a letter could do good and sent a letter to Ernest.[26] Steyn’s letter arrived later, for his chief concern was for the settlers from Cape Colony who had taken up arms for the Boers. This led him to delay his answer to the to the request led him to delay his answer to the request for a written statement of what he would do to bring the war to an end. “He would not betray the colonists in any event.” Ernest had succeeded in his mission in procuring written statements from both presidents of the Boer republics, which ultimately disproved the claims made by Chamberlain, that there was “a conspiracy on the part on the Boers to drive the British into the sea.” In fact, they were even willing to “surrender the fruits of the war gained in British territory.”[27]

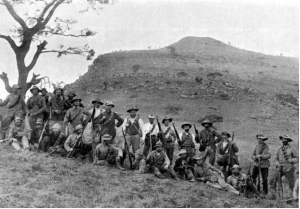

Spion Kopje.[28]

On January 24, 1900, the British lost, the “fifth of the series called the Battle of Spion Kopje,” where General Buller made an attempt to relieve Ladysmith. Churchill, who was present, stated it was “an event which the British people may regard with feelings of equal pride and sadness.[29] It redounds to the honor of the soldiers, though not greatly to the generals.” Ernest would state that Redvers Buller “led his armies into one mess after another, at Colenso, Spion [Kopje,] and elsewhere, and that Lord Roberts, with Kitchener as chief of staff, had to be sent out as commander-in-chief before the end of the year.”[30] Something that impressed Ernest was the “quietness” of Transvaal following the Boer victory. There was no public demonstration anywhere, so far as Ernest could see. The Boers believed the tide of war was in their favor, yet this belief stemmed not so much from their military strength, according to Ernest, but “of their belief in the power of God, who they felt sure, would give them the victory.”[31]

It was at this time (January 1900,) that the Outer Head sent word to the members of the Esoteric School could be classified into three classes. The first class consisted of the disaffected members thought the School to be dead. These members had failed the test, and the cycle had closed to them. The second class of members were called the “intermediate class” who doubted their inner conviction. These members were encouraged to fight on until they knew. The third class of members were those who felt the power and the guidance of the Lodge Force within them. It was only these members who had truly found the Outer Head. (Though it is unclear whether they met the Outer Head temporally or on the inner plane.) The circular stated:

First: Mrs. Tingley was Outer Head of the E.S.T. Those who announced that fact, and endorsed her as such, were entirely right in what they did, and carried out the wish of the Master. By the Master was she appointed, and by the Master deposed; the agent (E.T. Hargrove) who made the second announcement [deposing Mrs. Tingley] being as correct in that as he had been in the first. Any other hypothesis is untenable for those who believe that the School is guided by the Masters, for the link would have been broken otherwise, and the School left for a period to its own devices, in other words, deserted. Were this possible, the entire structure crumbles to pieces. Those who object to my remaining “unknown” will have to address themselves to the Master who appointed me, and by whose command that condition exists […] A democratic organization is essential at this time, when “no Master may come or send;” and when the School, therefore, must govern itself if receiving only interior inspiration.[32]

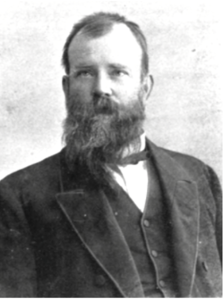

Ewald Esselen.

Francis William Reitz.[33]

Ernest learned from interviewing individual Boers that a thanksgiving service was had on the field of battle, and that the Boer General, Louis Botha, “offered up thanks to God for having blessed the burgher arms.” General Botha, struck Ernest as “a very forceful and able man, a great statesman and patriot as well as a great general,” and “the greatest man South Africa has produced.” He admired Botha’s humility, “[Botha was] not only unpretentious and free from egotism, but with a mind perpetually open, and as willing to learn from his enemies as from his friends, from his subordinates as from his seniors.” Ernest was convinced from talks, both with leaders, and with the rank and file, (who in many cases did not know who he was, or anything about him,) that the burghers were going to fight this war out to the end, and that their losses would “not affect them in the least,” because they believed that God was “chastising them temporarily, in His wisdom, and for His own purposes—just as He chastised the Jews on certain occasions perhaps in order to impress upon them the tact that victory would be due to Him, and not to their own strength.”[34]

Louis Botha.[35]

Ernest spoke with Ewald Esselen, a Boer Commando, and former State Attorney of the Transvaal Republic, who, like Ernest, studied law at the Temple. Esselen told Ernest that the commandos had sworn an oath among themselves, “that the survivors would bring up the children of those of the commando who were slain with this fact always before them, that their fathers had been killed by English troops while fighting for the freedom of their country.” The feeling amongst the Boers, Ernest observed, was that they were not only they fighting for their own freedom, “but for the moral, and intellectual freedom of their children—in so far as a conquered people, a people governed against their will by some stronger Power—no matter how well governed they may be—become liars, become, in fact, slaves to those who conquer them; they lose their self-respect, their manhood.” Many of the Boers admitted to Ernest that they would prefer to see their children dead, than to see them become subjects of a conquering nation. Ernest asked Esselen if he believed the Boers stood a chance against the British, should they ever reach Pretoria, to which Esselen replied:

There is no question of chance. We’ve got to do it, and I tell you why—It is not for our own sakes, it is for the sake of our children. I have seen something of the world; I have seen India and I know there that the Hindoos have almost lost their manhood; they have been slaves for a thousand years; subjugated, first, by the Musselmans, then by the British; they have lost their self-reliance and they have become more or less liars and hypocrites; that is the tendency, and I have been to Egypt and I have seen the Fellahs and I know that the same thing is true there. Do I want my children to live that sort of a life? No. It is a case of freedom or death, and if we can’t get freedom for them now, we at least have the right to die fighting for their freedom, and to leave that as a memory to them so that when their time comes they may do likewise.[36]

On the February 3, 1900, Francis William Reitz, the State Secretary of the Transvaal Republic, gave Ernest a signed letter to be presented to J. Van Kretschmar, manager of the Netherlands Railway Company, requesting him to pay Ernest the sum of £1,000 in connection for the “Conciliation Movement in Cape Colony.” Kruger did not wish to be directly connected in the affair, and fearing the accusation that Transvaal finances were being allocated “to win round public opinion.” The Netherlands Railway Company was a corporation which “employed large Secret Service funds in purchasing support in high places and in subsidizing opinion abroad,” whereby off-the-book political payments were debited to the Transvaal Government’s “Political Situation” account, settled at a later date.[37] Before leaving Pretoria on February 15, Ernest asked Reitz what truth there was in these “somewhat contradictory rumors” regarding Churchill’s escape.[38] Ernest writes:

I was in Pretoria during the latter part of January after Mr. Churchill’s escape. Before leaving this Colony I had heard various rumors to the effect, first, that he had broken his parole, and second, that the Transvaal Executive had purposely allowed him to get away. In Pretoria I had the pleasure of meeting Mr. Reitz, the State Secretary. I asked him what truth there was in these somewhat contradictory rumors. He told me that Mr. Churchill had never given his parole, and that it was impossible, therefore, for him to have broken it. Secondly, he told me that instead of Mr. Churchill having escaped with the connivance of the authorities, the authorities had done their utmost to recapture him on his absence becoming known. Mr. Reitz added, with the good nature which characterizes him, that Mr. Churchill had escaped by perfectly fair means. “I never saw him when he was here,” he said, “but I like what I have heard of his pluck and ingenuity, and now that he is beyond our reach I am free to say that it does him credit.”[39]

Ernest left Pretoria on February 15, and upon reaching to Lourenço Marques, he arranged for Kruger and Steyn to telegraph the substance of their conversations, which reaffirmed that their willingness to make overtures for peace on the basis of their independence, and to immediate withdrawal their forces from British territory. Border authorities for Cape Colony initially refused to grant Ernest re-entry without a pass, but Sauer intervened, and “gave himself much trouble to rescue his protégé and secured for him a special train.”[40] Ernest then helped establish the Cape Conciliation Committee, which held its inaugural meeting on March 12, 1900. Five days later, on March 17, a meeting was held in the Metropolitan Chambers. Ernest told the gathering of prominent Afrikanders a vivid account of the conversations which he had with Kruger and Steyn—which left quite an impression upon the audience. He told of how, in the midst of the of the Boer victories of Magersfontain, Colenso, Spion Kopje, he had repeatedly asked them this question:—“What do you desire of Great Britain?” He conveyed that, even then, their answer had been invariably:

Nothing but our independence. Do you not feel, Sir, that in the presence of such a fact, it is a calumny than to persist in gossiping about the Pan-African ambitions of these statesmen? And you must agree that slander against public figures, even Boer presidents, is in short just as odious as that which attacks private life?[41]

Paul Kruger, President of the Transvaal Republic.

Marthinas Theunis Steyn, President of the Orange Free State.[42]

Ernest then produced the telegrams he received from Kruger and Steyn in Lourenço Marques: “The Boer states are not fighting for land expansion, but for respecting their own rights […] We only want our political rights to remain respected, in peace as well as in the long run.” Ernest suggested that a petition of peace be drawn up to the people of Great Britain and Ireland, and a petition to be circulated among the American residents in Cape Town, urging both political parties in the United States “to keep the Boer question out of politics.” Both of these petitions Ernest would personally draft. In the ensuing three months, Ernest would make several platform appearances on behalf of the committee, in which he appealed to the “Cape Colonists to enlighten the people of Great Britain on the facts of the situation.” Sauer, for his part, would produce “wonderful eulogies” of Ernest in the South African News, which described him “as a high-minded, courageous, independent English gentleman without a business or profession,” and reported his speeches were at length.[43] Before the delegation sailed from the Cape more than 40,000 signatures were claimed for the people’s petition. In the move to campaign in England, Ernest had a prominent hand.[44]

On the same day (March 17) at the Talbot House, back in London, Leonard Courtney was elected President of the South African Conciliation Committee at the inaugural meeting. Connie Hargrove (Ernest’s sister) was elected to the Literature Committee at this meeting, and would work in disseminating the proposed Pro-Boer leaflets in England.[45] Rumor was rife as to the true identity of Ernest. It was reported, though no one was certain, that he “had once been a member of the English Bar, that he had subsequently gone to America, where he posed as a Theosophist, and had become mixed up in the sundry curious affairs.” Writing in September, 1900, B. Fletcher Robinson would report:

When I first arrived at the Cape in February, I heard a great deal of the doings of a certain English-American named Hargrove. He had openly expressed displeasure at the relief of Ladysmith while sitting in the Mount Nelson Hotel among a crowd of invalided officers from the front. It was indeed said that it was only the presence of a charming American wife that had saved him from being thrown into a fountain […] He had also stated that, though a British subject, he was so disgusted with the behavior of his countrymen, that he intended to become a naturalized subject of America, in which country he had been living.[46]

Ernest, very quickly, became a nuisance to the High Command of the Cape Colony. Word spread that Ernest had documents to prove that the Boer presidents were ready to make terms for the close of the war. When this matter became known to the British authorities, they began to devise their own plan to discredit Ernest. Richard Solomon, the Attorney General of Cape Colony, believed that Ernest “had a most mischievous influence in South Africa,” while Alfred Milner (who first learned of Ernest in November, 1899, “as the traveling-companion of Mr. Sauer,”) believed that Ernest was playing “a rather conspicuous part,” in the sowing civil discord in the Colony. According to Aimée, “[Ernest] never cared very much for just ordinary people, [he preferred] to exchange his ideas with people, or express his own views.” They met people at the Mt. Nelson, but Aimée and Ernest “never had any really particular social contact, because he was giving these lectures and everybody did just hate him.” Aimée states:

They opposed him to such an extent, why, they would send trucks out in front of the lecture halls and go up and down so that he couldn’t be heard, but he managed to talk over them in some way, and he was very sincere in his idea of stopping the Boer War. But I asked him, I said “Ernest, this is dreadful.” “Well,” he said, “it simply means that they simply don’t understand. We have to go on working. It is simply before my time.”[47]

By mid-April, British High Command had the evidence it needed to defame Ernest. Concurrent with the first meetings of the Cape Conciliation Committee was the Battle of Paardeberg, which resulted in the British capture of Bloemfontein (the capital of the Orange Free State.) Among the spoils of war were copies of the letters, signed by Kruger and Steyn, which stated their intention for peace should the British acknowledge Boer independence. A telegram from Kruger to Steyn, also seized, directly incriminated Ernest. It read: ”Confidential. January 20, 1900. A certain E. T. Hargrove, an English journalist, about whom Dr. Leyds formerly wrote…has come here, as he says, from Sauer and Merriman…” Merriman repudiated the affair altogether, while “Mr. Sauer contented himself with a denial that he had authorized Hargrove to convey a message to Kruger, though he did not deny that the message fairly represented his views. “[48] On April 19, 1900, Ernest received a letter from Merriman which read:

In a telegram from President Kruger to President Steyn, found at Bloemfontein, the following passage occurs:—”A certain Mr. E.T. Hargrove has come here, as he says, from Sauer and Merriman, who are ready to declare themselves openly on our side, in order to set on foot a propaganda in the Cape Colony, provided that an official declaration be given that the Republics only wish to secure their entire independence.” The inference is obvious, viz., that you were an emissary sent by Mr. Sauer and myself with a message to President Kruger offering on certain conditions to carry out a policy in this country, which would, to say the least of it, be incompatible with our position as Ministers in this Colony. I am at a loss to conceive how such a misconception could have entered the mind of President Kruger, or how I came to be mixed up in the matter. I should be extremely glad if you could afford me some explanation of this, to me, most unpleasant occurrence.

Ernest replied:

…This is not an answer to your note of this date, but is to ask you to allow me to show your note to a friend of yours and of mine. As it is marked “Private,” I cannot do this until I hear from you. Would you be so good as to send word by the driver of the cab which waits. The explanation of the matter is very simple. Meanwhile, be sure of one thing: that, as I never mentioned the subject referred to in that telegram in any talk I had with you before I left for the Transvaal, I never pretended when I got there to speak on your behalf, nor to know your views, and, of course, I made no kind of promise on your behalf. I hope to let you have a full explanation tomorrow. Sincerely regretting the matter, for which I think you will find that no one is to blame.[49]

Merriman forwarded Ernest’s letters to Prime Minister Schreiner, who subsequently messaged Milner: “It seems to me that Mr. Hargrove takes the thing rather easily…I confess that I cannot regard Mr. Hargrove’s explanation of his conduct as at all satisfactory.” Milner replied:

It appears that Mr. Hargrove is well satisfied with his explanation of his proceedings. I doubt whether anybody else is likely to share that satisfaction…I also think that the public are entitled to the enlightenment which this correspondence affords with regard to Mr. Hargrove, the nature of whose proceedings during his visit to the head of a hostile State appears to me to be of some public importance.[50]

“Sir Alfred Milner must have smiled grimly,” wrote the Gloucester Citizen, “when he appended his signature to the document ordering the seizure at the port of entry in Cape Colony of Mr. Stead’s pamphlet on the Scandal of the South African Committee on the grounds that it was “treasonable literature” Milner, in his younger days, sub-edited Steads “copy” for The Pall Mall Gazette. Milner, additionally, confiscated a pamphlet Reitz had written, “A Century of Wrong.”[51] Ernest, undaunted, continued holding Conciliation meetings. The pro-British press, however, made a coordinated effort to smear him at every opportunity. It was reported that a conciliation meeting on May 19, 1900, at Cradock, was broken up which resulted in riots. Another paper stated, “It is a well-known fact that wherever the Dutch agitator, Hargrove, goes his visits to the country villages is always followed by fresh outbursts of disloyalty.” Describing an incident at, Tulbagh, a village near, Cape Town, the paper states:

Here Hargrove went the other day, and itinerated some of [W.T.] Stead’s pamphlet’s and a few of his own ideas, with the result that now a feeling against the English is so strong, that it is not safe—in the interests of the general peace—for the soldiers who are guarding the line of railway close by to go into the dorp, and, in fact, orders have been issued at the instigation of the Boer Ministry here prohibiting the troopers from entering the precincts of this precious place…Fancy, British subjects and British soldiers, on leave, prohibited from entering a town in Her Majesty’s dominion for fear of an insurrection being caused by the sight of the uniform of Her Majesty’s forces.[52]

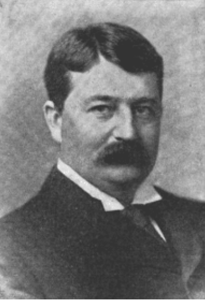

Sir Alfred Milner.

Prime Minister William Schreiner.[53]

A Conciliation meeting was held on May 30, 1900 in the town of Graaff-Reinet by the Volksonkgres (People’s Congress.) Among the matters discussed at the Congress the “best means of acquainting the British nation with the real facts of the South African situation and with the opinions of the Congress.” A resolution was carried that a mass petition would be conveyed to the people of Great Britain and Ireland, and a deputation from the congress would be sent to Britain “to tell the simple truth.” Ernest, the principle speaker of the event, addressed the Congress at length:

The term “pro-Boer agitator” had, he said, been applied to him as a term of opprobrium; he took it as a term of honor. (Cheers.) He believed he was agitating for the right. (Hear, hear.) He believed the Boers were in the right; he would continue to agitate for the justice of their cause. After his study, reading, and experience of South Africa, he could approve with all his heart the resolutions passed and about to be passed by the Congress…As English people they wished to see the Empire to which they belonged continue in the path of justice and honor, and not sink to the level of the Empires of old. An effort was being made to consolidate the Empire by force by ties which they called strong, having its center in London. Rome had tried to do the same, and fell to pieces. The ties must be elastic. At present the worst foes of the British Empire were not the Boers, but those who had set up the howl for annexation.…It had been sought to make this a question of race to blind the people of England, but he submitted it was not a matter of race, but of right and justice. Races might come and go, but justice stood always.[54]

At the close of his address, Ernest was given a vote of thanks and “tumultuous and prolonged applause.” B. Fletcher Robinson, who was in attendance, stated: “in the company of a number of the most violent Bond members who were outrageous in their denunciations of all things British,” and, “with the utmost violence [Ernest] denounced England, her soldiers and politicians…” Robinson, undoubtedly, could spin a yarn, as Arthur Conan Doyle could attest.[55] However, Ernest was not destined to be Robinson’s story in South Africa, for, after attending the Congress at Paarl on June 15, Ernest and “his charming American wife,” had seemingly vanished.[56]

Volkskongres Meeting On The Sports Ground, Graaf-Reinet, May 31, 1900.[57]

According to Aimée “The English Government got wind of the [meeting with Kruger,] and they were issuing a warrant for high treason against Mr. Hargrove, and another man by the name of [Arthur] Lynch, and when we heard that we immediately made arrangements to leave South Africa.”[58] As the political situation began to heat up, however, Ernest and Aimée snuck out of South Africa sometime in late July or early August. News from Cape Town had followed them. The special correspondent of the Daily Telegraph sent a message on August 9, 1900, which described the situation:

Much interest has been created by the publication in the Cape papers of the Merriman-Sauer-Hargrove correspondence, which has already appeared in the Parliamentary Blue Book. Further developments are certain, and may prove surprising. The temper in the Assembly is rising daily, and discreditable scenes are frequent.[59]

In August reports began filling the papers, that Ernest had been “bought off” by Boer authorities, painting him as a morally deficient opportunist, and traitor to his country.[60] A letter to the editor of The Pall Mall Gazette from a contributor who signed their name “Old Time,” connected him to the Theosophical Society:

Mr. Hargrove was a nice young man, picked up the trick of public speech rapidly, and might have done something at the Bar. I am glad to hear that, like some others of the “brethren,” he has now picked up “charming American wife;” but I’m sorry to find him mixing up in Cape politics and taking sides against his country. My story may assist your readers to judge from what motives he does so, and how far is counted with as a person of any importance.[61]

Other papers brought his family into the fray. “A curious cloud of personal mystery has come to surround the Mr. Hargrove whose name is now so frequently mentioned in connection with South African politics,” wrote The Liverpool Post, “[Ernest] is a younger son of Mr. James Sidney Hargrove, of 169 Queens-gate, chief of the solicitor firm of Hargrove and Co., 16, Victoria Street; and he is the nephew of the Conservative M.P., Mr. John Aird.”[62] (There were even poorly-written poems about him.)[63] “They really had issued the warrants for Mr. Hargrove,” Aimée would later say, “we didn’t know where to go, and Mr. Hargrove thought, well right in the center of the United States would be the best place to hide.” By looking at the ship manifests, we might be able to “connect the dots” to paint a picture of the Hargroves’ return to America. First, on August 31, 1900, a “Miss Neresheimer” arrives in Quebec, on the Tunisian. Knowing that the authorities (and the press) would likely be on the lookout for a man traveling with his “charming American wife,” perhaps they decided to travel separately. Using her maiden name, Aimée, being out of Emil’s good graces, perhaps, stayed with some Villa Maria friends in Montreal until Ernest arrived in New York.[64]

HARGROVE

I. “Refined English Atmosphere.”

II. “The Purple Mother.”

III. “Kitty Tingley, Despot.”

IV. “Villa Maria.”

V. “Dr. Leyds And The Occultation Of World Politics.”

VI. “The South African Situation.”

VII. “The Conciliator Of South Africa.”

VIII. “Transvaal Vs. Churchill.”

IX. “The Séances Of Thomas Welton Stanford.”

X. “The White Stag.”

XI. “The Hair Line Of Duty.”

SOURCES:

[1] Ridpath, John Clark. The Story Of South Africa. Oceanic Publishing Company. Sydney, Australia. (1899): 285.

[2] Hargrove, Ernest Temple “The White Man’s Burden,” in Addresses Delivered Before the Club During The Three Seasons, 1900-1903. Hausauer, Son & Jones, Printers. Buffalo, New York, (1904): 59-88.

[3] Hargrove, Ernest Temple “The White Man’s Burden,” in Addresses Delivered Before the Club During The Three Seasons, 1900-1903. Hausauer, Son & Jones, Printers. Buffalo, New York, (1904): 59-88.

[4] T. “On The Screen Of Time.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXXII, No. 1. (July 1934): 33-40.

[5] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 7613. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Ernest T. Hargrove.

Churchill, Winston Spencer. London to Ladysmith via Pretoria. Longmans, Green, and Co. London, England. (1900): 16.

Atkins, John Black. The Relief Of Ladysmith. Methuen & Co. London, England. (1900): 25-39.

[6] Mr. Hargrove entry; RMS Dunottar Castle Passenger Manifest, October 14, 1899, Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Outwards Passenger Lists. BT27. Records of the Commercial, Companies, Labour, Railways and Statistics Departments. Records of the Board of Trade and of successor and related bodies. The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, England.

[7] Churchill, Winston Spencer. London to Ladysmith via Pretoria. Longmans, Green, and Co. London, EN. (1900): 1, 10; Churchill, Winston. A Roving Commission: My Early Life. Charles Scribners’s Sons. New York, New York. (1930): 229-239.

[8] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 7613. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Ernest T. Hargrove.

[9] Atkins, John Black. The Relief Of Ladysmith. Methuen & Co. London, England. (1900): 25-39.

[10] Mount Nelson Hotel, Cape Town. Catalogue Reference: Part of CO 1069/214.. Colonial Office photographic collection held at The National Archives, uploaded as part of the “Africa Through a Lens project.” “Belmond Mount Nelson Hotel.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, March 5, 2021.

[11] “Notes And Comments.” The African Review. Vol. XX, No. 357. (September 23, 1899): 488-489; Atkins, John Black. The Relief Of Ladysmith. Methuen & Co. London, England. (1900): 40.

[12] Churchill, Winston. A Roving Commission: My Early Life. Charles Scribners’s Sons. New York, New York. (1930): 260.

[13] Churchill, Winston. A Roving Commission: My Early Life. Charles Scribners’s Sons. New York, New York. (1930): 259.

[14] “Our Captured Correspondent.” The Morning Post. (London, England) November 18, 1899.

[15] “Doctoring News.” City And State. Vol. XIV, No. 1 (January 1, 1903): 5-6.

[16] “Newspaper Misrepresentation.” The Lamp. Vol. III, No. 25 (August 15, 1896): 13-14.

[17] Murray, Richard William. South African Reminiscences. J.C. Juta & Co., Cape Town, South Africa. (1894): 103; “The Transvaal Concessions Commission.” The Times. (London, England) October 18, 1900.

[18] Great Britain, Presented To Both Houses Of Parliament. South Africa: Further Correspondence Relating To Affairs In South Africa. Darling & Son. London, England (July, 1900): 126; “Boer Gold And The Conciliation Movement.” Birmingham Daily Post. (Birmingham, England) August 29, 1900.

[19] “Noscitur A Socis” The Sussex Express (Sussex, England.) April 26, 1901; Noel, Geoffrey C. “Politics In South Africa.” The Fortnightly Review. Vol. LXIX, No. 8 (March 1, 1901): 508-519; Worsfold, William Basil. Lord Milner’s Work In South Africa From Its Commencement In 1897 To The Peace Of Vereeniging In 1902. E.P. Dutton. New York, New York. (1906): 287.

[20] Hillegas, Howard C. With The Boer Forces. Methuen & Co. London, England (1900): 214.

[21] “Will Fight On.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) November 29, 1900.

[22] “A Visit To Pretoria.” The North British Daily News. (Glasgow, Scotland) April 17, 1900.

[23] Hillegas, Howard C. “Pretoria Before The War.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. Vol. C. No. CXCVIII. (March, 1900): 348-357.

[24] McCracken, Daniel P. “From Paris To Paris Via Pretoria: Arthur Lynch At War.” Études Irlandaises. Vol. XXVIII, No. 1 (2003):121-142.

[25] As is often the case with media and politics, Churchill’s escape became a topic disembodied from Churchill himself. Churchill writes: “I found that during the weeks I had been a prisoner of war my name had resounded at home. The part I had played in the armored train had been exaggerated by the railway men and the wounded who had come back safely on the engine. The tale was transmitted to England with many crude or picturesque additions by the Press correspondents gathered at Estcourt. The papers had therefore been filled with extravagant praise of my behavior. The news of my escape coming on the top of all this, after nine days’ suspense and rumors of recapture, provoked another outburst of public eulogy…The statement that I had broken my parole or any honorable understanding in escaping was of course untrue. No parole was extended to any of the prisoners of war, and we were all kept as I have described in strict confinement under armed guard. The lie once started, however, persisted in the alleys of political controversy. Churchill, Winston. A Roving Commission: My Early Life. Charles Scribners’s Sons. New York, New York. (1930): 298.]

[26] The letter stated, in part: “We are not disinclined to make peace on the understanding that those of Her Majesty’s subjects who have assisted us in this war shall be allowed to return to their homes and shall be in no way punished or harmed, as we are firmly determined to stand by them to the end, and on the understanding that our independence shall be recognized according to International Law. This is the minimum that we can accept for the present. It is injustice that we should be subdued or wrong. If, after considering again all the circumstances, the British people and their responsible leaders determine that we deserve to be subdued, then there remains nothing for us but to fight to the very end, with God above us to judge between us.” [Great Britain, Presented To Both Houses Of Parliament. South Africa: Further Correspondence Relating To Affairs In South Africa. Darling & Son. London, England (July 1900): 127-128.]

[27] “A Visit To Pretoria.” The North British Daily News. (Glasgow, Scotland) April 17, 1900; “Will Fight On.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) November 29, 1900; Noel, Geoffrey C. “Politics In South Africa.” The Fortnightly Review. Vol. LXIX No. 8. (March 1, 1901): 508-519.

[28] Hillegas, Howard C. With The Boer Forces. Methuen & Co. London, England (1900): 132.

[29] Churchill, Winston Spencer. London To Ladysmith Via Pretoria. Longmans, Green, And Co. London, England. (1900): 312.

[30] T. “On The Screen Of Time.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXXII, No. 1 (July 1934): 33-40.

[31] “Will Fight On.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) November 29, 1900.

[32] Cooper, John. “The Esoteric School Within the Hargrove Theosophical Society.” Theosophical History. Vol. IV, No. 6-7. (April 1993-July, 1993):178-186.

[33] Amery, L.S. “ The Times History Of The War In South Africa, 1899-1902: Vol. I. Sampson Low, Marston And Company. London, England. (1900): 98; Souvenir Of The South African Republics. Head Office OF The Boer Relief Fund For The Relief Of Boer Widows And Children. (1900.)

[34] T. “On The Screen Of Time” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXXII, No. 1. (July, 1934): 33-40.

“A Visit To Pretoria.” The North British Daily News. (Glasgow, Scotland) April 17, 1900.

[35] Hillegas, Howard C. With The Boer Forces. Methuen & Co. London, England (1900): 4.

[36] “A Visit To Pretoria.” The North British Daily News. (Glasgow, Scotland) April 17, 1900.

Hargrove, Ernest Temple “The White Man’s Burden,” in Addresses Delivered Before the Club During The Three Seasons, 1900-1903. Hausauer, Son & Jones, Printers. Buffalo, New York, (1904): 59-88.

[37] South Africa: Report of the Transvaal Concessions Commission. Wyman and Sons. London, England. (1901.): 34.

[38] “A Visit To Pretoria.” The North British Daily News. (Glasgow, Scotland) April 17, 1900.

[39] “Mr. Winston S. Churchill’s Escape.” The Morning Post. (London, England,) May 7, 1900.

[40] “A Visit To Pretoria.” The North British Daily News. (Glasgow, Scotland) April 17, 1900; “Will Fight On.” The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts) November 29, 1900; Noel, Geoffrey C. “Politics In South Africa.” The Fortnightly Review. Vol. LXIX No. 8. (March 1, 1901): 508-519; “The Netherlands Railway.” The African Review. Vol. XXVII, No. 448 (June 22, 1901): 450-451; Cook, Edward Tyas. Rights And Wrongs Of The Transvaal War. Edward Arnold. London, England. (1901): 16-17.

[41] Vlugt, Willem. Les Vrais Coupables: Lettre à Monsieur Ed. Tallichet, Rédacteur de la Bibliothèque Universelle et Revue Suisse. J.H. de Bussy. Amsterdam, Netherlands. (1900): 31.

[42] Bigelow, Poultney. White Man’s Africa. Harper & Brothers. New York, New York. (1898): 20, 80.

[43] “Was Moet Gedaan Worden?” One Land. (Cape Town, South Africa) March 20, 1900; “A Visit To Pretoria.” The North British Daily News. (Glasgow, Scotland) April 17, 1900; “Cape Colony.” The Times. (London, England) May 21, 1900; “Boer Gold And The Conciliation Movement.” Birmingham Daily Post. (Birmingham, England) August 29, 1900; “Will Fight On.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) November 29, 1900; Noel, Geoffrey C. “Politics In South Africa.” The Fortnightly Review. Vol. LXIX No. 8. (March 1, 1901): 508-519.

[44] Davey, Arthur. The British Pro-Boers 1877-1902. Tafelberg Publishers. Cape Town, South Africa. (1978): 97-98.

[45] South Africa Conciliation Committee. The South Africa Conciliation Committee List Of Names And Addresses. National Press Agency. London, England. (1900): 3.

[46] Robinson, B. Fletcher. “Ernest Temple Hargrove.” The Evening Post (Dundee, Scotland.) September 1, 1900.

[47] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove.

[48] Great Britain, Presented To Both Houses Of Parliament. South Africa: Further Correspondence Relating To Affairs In South Africa. Darling & Son. London, England (July, 1900): 126, 127-128.

“Will Fight On.” The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts) November 29, 1900.

Robinson, B. Fletcher. “Ernest Temple Hargrove.” The Evening Post (Dundee, Scotland.) September 1, 1900.

Noel, Geoffrey C. “Politics In South Africa.” The Fortnightly Review. Vol. LXIX No. 8. (March 1, 1901.): 508-519.

In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove As a Will of Real and Personal Property; Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York, First Department Jun 27, 1941; 28 N.Y.S.2d 571 (N.Y. App. Div. 1941)

[49] Great Britain, Presented To Both Houses Of Parliament. South Africa: Further Correspondence Relating To Affairs In South Africa. Darling & Son. London, England (July, 1900): 130, 131.

[50] Great Britain, Presented To Both Houses Of Parliament. South Africa: Further Correspondence Relating To Affairs In South Africa. Darling & Son. London, England (July, 1900): 132.

[51] “Our London Letter.” The Citizen (Gloucester, England.) April 30, 1900.

[52] “Cape Colony” The Times. (London, England) May 21, 1900; “Our Capetown Letter” The Derby Mercury. (Derby, England) June 6, 1900; In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove As a Will of Real and Personal Property; Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York, First Department Jun 27, 1941; 28 N.Y.S.2d 571 (N.Y. App. Div. 1941)

[53] (Milner) Amery, L.S. “ The Times History Of The War In South Africa, 1899-1902: Vol. I. Sampson Low, Marston And Company. London, England. (1900): 251; (Schreiner) “The Progress Of The World.” The American Monthly Review Of Reviews. Vol. XX, No. 4 (October 1899): 387-406.

[54] Davey, Arthur. The British Pro-Boers 1877-1902. Tafelberg Publishers. Cape Town, South Africa. (1978): 97-98.

Great Britain, Presented To Both Houses Of Parliament. South Africa: Further Correspondence Relating To Affairs In South Africa. Darling & Son. London, England (July, 1900): 188.

[55] Arthur Conan Doyle, who met Robinson in South Africa at this time, would admit as much in 1902, in the dedication of The Hound of the Baskervilles: ”My dear Robinson: It was the account of a West Country legend which first suggested the idea of this little tale to my mind. For this, and for the help which you gave me in its evolution, all thanks.—A. Conan Doyle.” [Doyle, Arthur Conan. The Hound of the Baskervilles. McClure, Phillips & Co. New York, New York. (1902) dedication.]

[56] Robinson, B. Fletcher. “Ernest Temple Hargrove.” The Evening Post (Dundee, Scotland.) September 1, 1900.

[57] “Volks Congress Meeting.” Black And White. Vol. XX, No. 492. (July 7, 1900): 36.

[58] “Cape Ministerial Crisis.” Dublin Daily Nation. (Dublin, Ireland) June 13, 1900; Great Britain, Presented To Both Houses Of Parliament. South Africa: Further Correspondence Relating To Affairs In South Africa. Darling & Son. London, England (July, 1900): 188; Fletcher-Vane, Francis P. Pax Britannica In South Africa. Archibald Constable & Co. (1905): 365; In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove As a Will of Real and Personal Property; Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York, First Department Jun 27, 1941; 28 N.Y.S.2d 571 (N.Y. App. Div. 1941)

[59] “Treason Debate At The Cape.” Lancashire Evening Post. (Lancashire, England) August 10, 1900.

[60] “Notices” The Morning Post. (London, England) June 20, 1900; “Boer Gold And The Conciliation Movement.” Birmingham Daily Post. (Birmingham, England) August 29, 1900.

[61] ‘Old Times.’ “Hargrove And Cape Politics.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) September 10, 1900.

[62] “Mr. Hargrove.” Liverpool Daily Post. (Liverpool, England) September 1, 1900.

[63] “In Khaki-land, what avatar? What topic holds the London diner? Methinks the self-same natal star. On Hargrove shown and Cronwright-Schreiner. Hargrove (at Boshfontein) gives news. As spokesman for the British nation; While Cronwright airs ‘Colonial Views (At Rugby) on Conciliation.’ At Home, ‘Who’s Hargrove?’ No one knows. At Capetown, ‘Who’s this Cronwright-Schreiner?’ Much virtue in a change of clothes. And two weeks on a Castle liner! Then Hargrove spouts to serried ranks, Rebels (on bail) applauding madly; E’ev Cronwright charms selected cranks. (The people nowhere hear him gladly.) Could Hargrove stump the British Isles? Could Cronwright voice the Brave and Free. Nearer than some six thousand miles? A prophet does not boom chez-lei! ‘Tis economic truth, we own, That things, to sell, must first be sorted; These two, no use where they were grown, Command high value when exported. What bathos, after all these jigs, To mutually repatriate. And live once more well-meaning prigs. Whom no one cares to hear orate! So, swapping domiciles, and fame. Assuaging exile for the two, Hargrove and he of duplex name. Bore brother Boers till all is blue.” [F.E.G. “London, Wednesday, Aug. 1.” Daily News. (London, England) August 1, 1900.]

[64] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove As a Will of Real and Personal Property; Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York, First Department Jun 27, 1941; 28 N.Y.S.2d 571 (N.Y. App. Div. 1941); Passenger Lists, 1865–1935. Microfilm Publications T-479 to T-520, T-4689 to T-4874, T-14700 to T-14938, C-4511 to C-4542. Library and Archives Canada, n.d. RG 76-C. Department of Employment and Immigration fonds. Library and Archives Canada Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. (Library and Archives Canada; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; Series: RG 76-C; Roll: T-479.)