On May 11, 1905, their ship, the S.S. Grosser Kurfurst, arrived in New York, and they promptly made their way out West.[1] Emil and Minnie were previously living at Point Loma; according to Aimée, Emil had surrendered his money to Tingley, and she directed him “to go out and make some more…”[2] Emil subsequently went to Colorado to establish an irrigation project that was promised “to make a large section of arid land blossom like the rose.”[3] The project called for the construction of a huge reservoir in Bloomfield for the purpose of irrigating 200,000 acres of land east of Denver. An option was secured by Holland and Denver capitalists on 14,000 acres as a site for the reservoir, which cost $2,000,000. This called for specialized legal expertise. Emil sought the assistance of an old associate of from New York, Milton Smith, who was also the Chairman of the Democratic State Central Committee of Colorado.[4] Hargrove’s connection with his Dutch associates would also prove useful, and he was hired by Emil to raise the initial capital for what would become the Denver Reservoir & Irrigation Company.[5] Given the Dutch connection, it is possible that Leyds was involved, as Ernest advised him on other share investments in the United States.[6] After residing for a few months in Boulder, Emil and Minnie moved to Denver. The Hargroves soon followed and purchased a “splendid home” at 1441 Elizabeth Street. Aimée moved immediately, while Ernest remained in Boulder to settle affairs.[7]

Milton Smith.[8]

The headlines in the summer of 1905 would only have strengthened Ernest’s notion that newspapers “fail to understand.”[9] On August 5, 1905, The San Francisco Examiner printed an article, “Loot Of Egyptian Tombs Declined By Dr. Jordan: Treasure Gathered By Mahatma’s Are Tabooed,” in which it was stated that David Starr Jordan refused to accept a donation from T.W. Stanford consisting of apports from Charles Bailey’s séances. Jordan stated: “In all cases of the alleged spirit manifestations which I have any knowledge of the plain explanation lies in the nature of the nervous condition of the so-called mediums,” Dr. Jordan said.[10] Ernest was growing more restless in his desire to return to Theosophy and began to write articles for the Theosophical Quarterly. A book review written for the October 1905 issue of the Quarterly for Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis by “H.,” contains enough clues to confidently identify “H” as Hargrove and—glean some insight Ernest’s thoughts upon returning to America:

This is not a review. It is a talk about a man and a book. I have been reading the book with profound emotion—if sympathy can thus be described. It is the revelation of a man’s soul, as it was before and as it was after the fire of life had purified it. And by Oscar Wilde […] His earlier books have a wide and not always healthy influence. They have been translated into several European languages, and in Germany have become almost popular. Most people preserve a hasty recollection of his story: well-born, the leader of the aesthetic movement in England, a poet, dramatist, novelist, art critic (or guide), and in that capacity a keen fencer with Whistler. Brilliant success, and then a libel action, in which he sought to defend himself against a charge of gross immorality; his arrest, when his defense had failed, and finally his imprisonment and awful disgrace. He wrote this book while still in prison, in order to unburden himself to a friend. The crime he had committed was perverse and unnameable; but men who deplored his offense stood by him to the end, when, some two years after his release from prison, death robbed them of all but his memory. To that also his friends have been loyal […] In these circumstances, what did Life, the great compassionator, do to him? Life, or the Soul of things (of which his soul, too, was a part, let us remember), seems to have thought that there was something in him which made him worth saving; something, in any case, which entitled him to a chance to save himself: for Life went to work, elaborately, to break his heart, to break his vanity, to break his stubbornness. It melted him. But it was not punishment that Life inflicted. Wilde punished himself.[11]

Aimée, who arrived in Denver a few weeks before Ernest, quickly grew fond of the family Emil’s lawyer, Milton Smith. Milton had told his wife, Susan, that he was going to help the Neresheimers integrate in Denver Society. “A few dinner parties, [and] an evening or two at the theatre will rehabilitate me in the eyes of your friends, my dear, and make a good impression on our new friends.” Susan, evidently aware of her husband’s past indiscretions, was suspicious of Milton’s intention; she opposed this plan from the beginning.[12] “[Susan] protested gently against any lavish display until the friends who had ever stood loyally with her should become willing of themselves to again receive her husband, who had wandered so far away from the conventional paths.”[13]

Aimée then became friends with Ruth Leavitt, the daughter of Democratic Presidential nominee, William Jennings Bryan, who, like Aimée, was a young wife, and the mother of an 11-month-old. The Leavitt’s were staying in Denver after escaping an outbreak of Yellow Fever in New Orleans earlier that summer. Ruth, who was due to give birth to their second child that November, had written a one-act play, “Mrs. S. Holmes, Detective,” for Denver’s Orpheum Circuit, to prove to her friends “that the Nebraska girl could keep her word to write a better play than the one they were witnessing.”[14]

“Mrs. Ruth Bryan Leavitt And Her Two Little Children.”[15]

During one of Ernest’s absences, Aimée invited Milton and Susan to a dinner party she was hosting, in honor of Ruth. Milton accepted, while the increasingly suspicious Susan declined. At the dinner, Aimée is quoted as saying: “dear Mrs. Smith was to be the guest of honor.” Milton added that Susan was “as usual, not well.”[16]

Wherever one couple was seen, the other would put in an appearance. When the Smiths were not dining the Hargroves, the Hargroves were entertaining the Smiths. Many times Mrs. Hargrove would pick up Mr. Smith in her electric brougham and drive him home in the late afternoon from his office, stopping for a cheery word with Mrs. Smith, who with an intuition made keen by past suffering and humiliation, readily perceived the direction in which the straws were blowing […] When every man, woman and child who lived in the Hargrove neighborhood were discussing the friendliness of Mrs. Hargrove, and the Chairman of the Democratic State Central Committee, Ernest Hargrove’s ears were closed.[17]

Aimée had reached her limit in the relationship. The dynamic was never particularly harmonious for the couple, but Aimée was growing increasingly troubled by Ernest’s behavior. Speaking of the discord of their home life, Aimée would say:

Such an accumulation of small things, it seems so trivial when you tell it […] It was always about the children…It was mainly about their diet and he had such fixed ideas about how they should be brought up and I had my own ideas as to what they should eat and what they should do and their routine of the day and [Ernest] became very irritated about my ideas about the children. I sort of felt that my ideas were the practical ideas and Mr. Hargrove always looked in the book to decide what the children should have […] He had the idea that they should eat mainly starches, and then he had an idea that they should have their bowel evacuation […] long before they ever had any breakfast and we would argue and argue until I was quite frantic over the situation […] It was always about the children. They seemed to irritate him very much It was all on account of the withdrawal He was withdrawing all the time from me and the children he really wanted to go back to Theosophy.[18]

By the time Ernest arrived in Denver (November, 1905) Aimée was comfortably established, leaving Ernest able to travel widely back east and overseas on matters of business. He was away from Colorado a majority of time “from November, 1905, to the month of November, 1906.”[19] In early June, 1906, Ernest was preparing for another trip overseas; and filed for a new passport, with Emil acting as his witness.[20] Denver society was occupied with Colorado Derby Day, which opened the horse racing season at Overland Park on June 16. Over 1,500 people were attendance, in weather that was oppressively hot, or, as the papers described it, “sultry.”[21] The Hargroves and Smiths were in attendance, spending the afternoon at the Denver-Overland Racing Club. Milton and Aimée had grown more brazen with their flirtation, and disappeared together for some length. Susan sent an attendant to notify Milton that she was ill, and was preparing to leave, either with him, or with friends. Susan could no longer endure the humiliation.

When the couple returned reluctantly, [Aimée,] with blazing eyes, walked to where [Susan] was sitting and said: “I am sure, my dear, I don’t want you to think that I have any desire to take your husband from you—not at all, my dear—and in the future you don’t need to send for him.”[22]

Ernest, seemingly untroubled, or oblivious, was preparing a paper, The Hair Line Of Duty, for which he would read at the T.S. of England during his upcoming trip. In it he writes:

I shall perhaps be told’ that Madame Blavatsky said, “Judge the act and not the actor”—or words to that effect. But what did she mean by this? Did she mean that we should condemn the lie which our Brother Smith told yesterday? Or did she mean that we should condemn lying? I think the latter. You will observe the distinction. Did Brother Smith lie? Do you appreciate the luxury of not having to decide that point? Do you realize how much trouble and energy it saves, how much easier life becomes, if we reserve a large pocket in our minds for—”I don’t know. Thank God, I do not need to know. This is no business of mine.” My pocket of that nature is indefinitely elastic: otherwise it would have burst years ago. The number of things—other people’s things—about which I have no opinion at all! All of us, doubtless, are in the same position. But, you may say, this is laziness; this is shirking life’s duties: we must judge; we must not blind ourselves to self-evident wrong. Is it laziness? I call it conservation of energy. Is it shirking life’s duties? I call it adhering to one’s own duty and avoiding interference with the duties of others—duties which, we know, are full of danger. We must judge; certainly: we must judge our own conduct in the light of our own highest ideal, and if we do that conscientiously and thoroughly we shall be kept busy enough. But then comes the climax: we must not blind ourselves to self-evident wrong. No, we must blind ourselves to nothing that concerns us, or that can affect the proper discharge of our duty. Let me suggest, however, that if we are looking for wrong we shall find it pretty well everywhere (this incidentally); that what concerns us chiefly is our performance of the right, and that the wrongs committed by others are best counteracted, not by condemnation or by direct opposition, but by creative work along the line of the ideal. And this is work which in any case we ought to be doing with all our might.[23]

In the essay, Ernest admits:—“I have just read this paper to a candid and excellent friend, who tells me that it will strike the ordinary listener as monastic, chilly and exclusive; and that it will be understood as recommending a withdrawal, almost a separation from humanity.” This begs the question:—Which friend would Ernest be talking to in Denver? According to Aimée:

Every time [Ernest] would be home, he would either be writing, or be meditating in his room with the door locked. He was not writing for anybody in particular, he was meditating and he would receive these messages that he would write down. He was always very pleased with these messages They were messages from Mr. Judge like you would receive messages from persons…He finally explained that “that is just because the world is not ready for me, we will just have to forget it on that account.” But when he began to receive these messages I noticed that he had on every other line would he the word Christ—he got the Christ idea at that time—he would go to bed and have a notebook next to him, and then he would wake up in the morning he would show me these things that he had heard during the night.[24]

In July, while Ernest was in Europe, Minnie, Emil, and Aimée joined the throng of “automobile tourists,” who made their way to Colorado Springs from Denver. Milton and Susan entertained their auto party on July 10 at the Casino Hotel. [25] “We are so glad daughter likes [Milton,] so much,” Emil is quoted as saying, adding, “he is such a charming man and we like him so much.” Soon after, Susan and her two children left for Long Island, where they stayed for the remainder of the summer.[26] In her absence, it was rumored, “[The] Smith auto became practically the property of [Aimée.]” Emil and Minnie encouraged Milton’s visits, “feeling sorry for his loneliness, since his family had gone away.” The summer passed, and “every day the Smith car, flying about with [Aimée] or her two lovely children dashed through the streets of Denver.”[27]

“A Colorado Home, And Its Mistress Driving Her Own Automobile.”[28]

When Ernest returned from Europe, in August, 1906, Aimée announced that she wanted a divorce, saying “You interfere entirely too much with my discipline and bringing up of the children. I don’t love you, and if I have to live with you another hour I shall die.” Ernest was shocked that Aimée wanted a divorce, and told her that “there was no occasion for it, and that [Aimée] had no grounds for a divorce.” Aimée, allegedly, told Ernest, “I will make your life such a Hell that you will be compelled to agree to [a divorce.]“ She told Ernest to confer with the family attorney, Smith, for advice on how to proceed with the matter. Ernest went to Smith, and “poured out his whole story,” explaining that he loved Aimée, “how he would willingly die for her. He told of her moods and tempers, of her vanity, her childish ways, of her impatience at restraint, and asked for advice.” Milton told Ernest that Aimée had a clear case for divorce, and recommended that Hargrove not fight it, but rather “make a provision for her and the children,” adding that, perhaps, after some time, “she will see the error of her ways.” Ernest listened to Milton’s advice, and asked him to appear on his behalf in the court proceedings “and save all the unpleasant publicity.”[29]

Strictly speaking, in 1906 Colorado, there was no legal basis for the divorce, and on that accord Aimée agreed: “Of course we didn’t [have a reason for divorce.] It was only [on the grounds of] the children, and that [Hargrove] was very unhappy and wanted to leave me just as much as I wanted to leave him. That was perfectly understood.”

On September 1, 1906, Milton met Susan and the children at the train station after they had returned from a summer by the sea. All summer, “letters had been sent to her telling her of the devotion of her to his client’s wife.” In the car ride home Milton told his wife, “This has got to end, Susan. I want my freedom. I have enjoyed my summer, not having to account for anyone, and I want to be free to go from one to another. You know my weakness, and I won’t be bound—that is, I won’t be bound after Election Day.” Just before Susan’s return, Milton, in his capacity as Chairman of the Democratic State Central Committee of Colorado, announced that the State Democratic convention would be held in Denver, at Coliseum Hall on September 11. The convention promised to be the most notable in the history of Colorado. “The destiny of the party in the state would be fixed at the convention, “every loyal democrat and citizen having fully determined that the party shall cut loose from corporate influences and elect men who will serve the people.”[30]

The State convention of the Democratic Party was called. A Democratic convention in Colorado does not usually make an appeal to polite society. To be sure, there is always a certain number of women delegates who go and sit through the days of loud talk and tobacco smoke, who vote and speak when they have anything to say, but as a rule, unless it is an imperative duty, women do not go to a Democratic State Convention. Milton Smith, by virtue of his office as State Chairman, called the convention to order. Watching his every move from a corner under the balcony sat Mrs. Hargrove. The woman, who affects white lace gowns, Parisian lingerie, and abhors anything rough and untidy, sat through the long hours of the convention, even attending the evening session, wearing a dainty frock of white and black checked voile, with a chic French hat perched on her coiffure.[31]

In late October 1906, representatives from the Colorado Democratic Party went to Nebraska to enlist the help of William Jennings Bryan, “the great commoner, the hope of national democracy,” to aid the failing campaign in Colorado. It was said that Bryan balked at the hypocrisy of Chairman Milton Smith, the corporate attorney who was supposed to represent the working-man, had instead “tainted” the image of the party. Bryan eventually consented, and arrived in Denver, only to go back on his offer of endorsement.[32] It was stated:

Mr. Bryan came to Colorado unaware of the situation in the Democratic Party. He did not know that Milton Smith, the Chairman of the State Committee, was the attorney for half a dozen corporations, against which Boss Patterson has howled so assiduously for years…When he did learn the facts he refused to be a party to the Patterson fake campaign, and he left as soon as possible for the East.[33]

William Jennings Bryan c. 1905.[34]

The Democratic Party continued the last leg of the campaign under the sole command of Milton Smith; “on his disposition of affairs depended much of the success of his party.”

Whenever the leaders came from various parts of the State to see Mr. Smith, his clerks at the headquarters informed them that if they would take chairs and wait he would be in shortly—he had just gone out. He had really gone out just for a breath of fresh air to give his judgment on some purchase that Mrs. Hargrove wanted to make, but was afraid to rely on her own judgment. So the leaders sat, and waited and fumed and swore that they wished “women were in the bottom of the sea and stay there until after the election.” “Blast the petticoat government of this campaign,” became the slogan of the malcontents.[35]

Ernest, meanwhile, continued his meditation practice, and others were following suit. In 1906 Henry Bedinger Mitchell published Meditation—readily acknowledging his indebtedness to Cavé’s method, stating that it was “the clearest and concise exposition readily available […] giving an insight the present writer cannot hope to impart.”[36] The (New York) Theosophists back in New York were beginning a new plan of action, a monthly salon in Mitchell’s home, in which topics of science, philosophy, and religion were discussed. (Those talks can be read here.) In later years Ernest would publish a letter in his possession, written by Cavé in 1906 “to a man whose mind at that time had the habit of grinding over hypothetical and therefore unnecessary problems.” The contents of the letter would suggest that the unnamed recipient was Ernest:

I am glad to hear you speak as you do of an opening of a life of opportunity and service seeming to stretch before you, because, first, that in some measure is the way we always should feel, and we are more truly alive and in touch with realities when we do feel it. Second, because I feel that it is peculiarly true of you at present. Your life has indeed been given back to you by those to whose service you long ago dedicated it, and so in a particular way it is theirs and for their work. I know that you feel thus of it and so can speak frankly. The first thing I would tell you therefore, is do not be too analytical; do not try so much to satisfy the brain. What right has it to be satisfied? You are to remember the ‘day of small things,’ that is, to-day, in its wonderful aspect of small tasks and duties following one after the other each moment. That is what concerns you. While looking ahead, while puzzling over this aspect of the question or that, how many of these little immediate duties slip away undone? There is only one question you need ever ask yourself; that is, What is the duty of this moment? That is the Master’s task for you; this moment and its proper employment. Until we have learned how to do that, we cannot be entrusted with greater tasks, since those greater ones are only properly performed when done in that spirit of perfect recollection; for, really, recollection is what we are talking of here—that, and its twin brother detachment.

If you will model your life on this plan you will find numberless chances of service ahead of you and you, will find that you can perform them all easily and well. We speak of life as complicated, but we are mistaken: life is extremely simple. We are complicated; because partaking of two natures and of divided will, we grasp in all directions, determined to serve both God and Mammon, to have both heaven and earth and the fulness of them. And we tangle ourselves in mixed motives, mixed emotions, apprehensions and regrets, until the only wonder is that we are not all quite mad. If you consider this deeply you will see that it is the secret of true living, for it is an aspect—the first—of continuous meditation. It rids life of all complexity and difficulty (puts them where they belong, in ourselves), and shows us the ‘small, old path,’ narrow and straight that we have learned to call ‘the path.’ By this method also we are rid of the complexities and hindrances in ourselves—since we must ignore them to follow it. Our attention is immovably fixed on one point. Do not then look ahead so much; while planning the future you lose the present. This is where I should say you had been careless,—careless of so many ‘little things’ because you were pondering over bigger ones. Until these arrived they were not yours. The future does not belong to us—may never be ours; this moment is all we really possess. Each one is a special gift—how will you use it? You wish to give your life and service to the Master; there is but one way in which to do this: give it moment by moment as it comes to you. In this way the life of an ascetic can be lived in the midst of luxuries and splendor; the life of a saint in a world steeped to the lips in folly and sin.

We must remember for our consolation, in view of our many failures and backsliding, that we are attempting a work of much difficulty indeed one which has not been ventured upon previously, but which as you know was made possible by the unprecedented success in the Movement this last century. Whatever may come, we have at least been in some humble fashion instrumental in pushing so far forward, and by earnest effort and abiding faith may hope to accomplish yet a few paces more before our time is up. Each year we carry this on is so much clear gain—think of that. For so long as the nucleus exists, the work must exist on this plane. And we must strengthen that nucleus by all means in our power; and no means can be more effective than the raising of ourselves, thus bringing down more of the divine force and light to this plane, increasing our ability and sphere of usefulness, and by treading down this new path in the wilderness, making it easier for others to follow on after and to find the way.

That quality which carries one through when tested is what we are the—accumulation of aspirations, devoted efforts, high motives, sacrifices which form a living force that pushes us through. Even our sins, thank God! cannot withstand it. For the rest, I say again, do not analyze; they are brain questions and, however good in themselves, do not really concern us nor the tasks we have in hand. This is not to discourage further questions, however; far from it. But I like best those ‘springing from the heart,’ in the words of the old Chinese aphorism. Your mind is wanting to know many things. Yes, of course; that is the way with minds. But hush, hush, oh! Mind, lest in the midst of your ceaseless chatter I fail to hear the voice of the Master which speaks to me in the Silence.

May the Master bless and keep you, and cause his light to shine upon you, and give you peace. Amen.[37]

The Democratic party was defeated in the November election. It was stated “emphatically that had there been less shopping and more active management on the part of the Chairman, who is acknowledged to have a genius for executive management, the defeat would have been less severe, at least.” After the election, Milton told a nonplussed Susan that he was in love with Aimée. Ernest, however, was unaware of the reality of the situation. A lawyer working for Milton appeared on behalf of Ernest during the divorce proceedings, and “conforming to the established order by asking a few simple questions, after which the court instructed the jury to bring in a verdict for the plaintiff, giving the children into her care.” Ten days later, Milton announced to Ernest that he was going to marry Aimée he “hoped there would be no hard feelings.”[38] On January 15, 1907, two days shy of what would have been her eighth wedding anniversary with Ernest:

Aimée Hargrove, 24 years of age, spinster, and Milton Smith, accompanied by an aged man giving his name as Mr. Hargrove, presumably the father of the bride, who was witness to the marriage if the couple. The aged man was [E.A.] Neresheimer, the bride’s father, who had assumed the name of his cast-off son-in-law to avoid the asking of unpleasant questions by the minister.[39]

Initially Ernest was somewhat accepting of the situation; he would visit the children who now lived at the home of Milton Smith and Aimée. He would play with the children in the sandpile, but, according to Aimée:

[Ernest] would keep them out so late that I would have to go out and get them, and that, of course, entailed conversation with [Ernest,] and of course we would immediately start arguing again about the children and their bringing up, and then just about that time usually [Milton] would come home and he would settle the argument by inviting [Ernest] to dinner.[40]

In July, 1907, Ernest, believing he had been deceived, filed a petition charging Aimée and Milton with conspiracy, and began a “suit to recover the custody of his children, given to his wife by the court.” Ernest argued that Aimée had violated Colorado law which stated that divorcees could not marry within the same year that a divorce was granted. During this time, it was alleged, that Ernest, in an interview with Aimée, insisted that she “must confess the whole truth to him.” Ernest, swore, under oath, that Aimée had confessed her infidelity to him, and had “cohabited with other men,” and provided their names; “a German doctor by the name of Weidner,” and “the name of a man in Chicago,” and “suggested to [Ernest] that while he was away on trips, [she] had been intimate with other men, and that they were the fathers of these two children.” Aimée would deny that this conversation ever took place. According to Aimée:

[Ernest] lost the case. And he was still in business with my father, but he became very excited at that time, and he took the books of the company over to his hotel, and he locked himself in there with a gun—this is absurd of course.[41]

The story was reprinted in nearly every state. Clem was very anxious to remove Hargrove from the situation in Colorado “and all the associations there” and bring him home to New York to be closer to him, his “brother.” The Theosophists back in New York (Clem, Mitchell, and Johnston) were growing concerned over Percy Grant’s Forums at the Ascension, and they had an idea for the Mission Chapel.

[Clem] was very interested in it, but he was such a very busy man himself that it was not possible for him to give the personal attention to it that it required, and under the impression that [Ernest] was then free, the divorce had been completed and so on, [Clem] asked him if he would come on to New York and look the situation over, see what the work was like, meet the people who would be associated with him in it, and decide whether he could come or not; and his first visit was for that.[42]

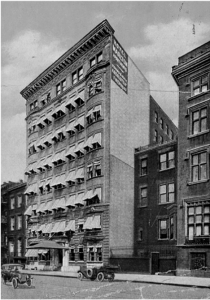

“It was in the spring of 1908,” it was said, “that Clement Acton Griscom, then a Vestryman in the Church of the Ascension, wrote to his friend, Ernest Temple Hargrove, asking him to come to his help in what he felt to be an important work.”[43] Ernest soon arrived in New York, taking up a room in Greenwich Village’s Hotel Marlton, not far from the Church of the Ascension.[44]

Hotel Marlton.[45]

HARGROVE

I. “Refined English Atmosphere.”

II. “The Purple Mother.”

III. “Kitty Tingley, Despot.”

IV. “Villa Maria.”

V. “Dr. Leyds And The Occultation Of World Politics.”

VI. “The South African Situation.”

VII. “The Conciliator Of South Africa.”

VIII. “Transvaal Vs. Churchill.”

IX. “The Séances Of Thomas Welton Stanford.”

X. “The White Stag.”

XI. “The Hair Line Of Duty.”

SOURCES:

[1] Ernest T. Hargrove entry; SS Grosser Kurfurst Passenger Manifest, February 1905; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957; Microfilm Roll: Roll 0571; Line: 26; Page Number: 66.

[2] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove As a Will of Real and Personal Property; Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York, First Department Jun 27, 1941; 28 N.Y.S.2d 571 (N.Y. App. Div. 1941)

[3] “An Attorney Steals His Client’s Wife And In Turn Discards His Own.” The Fairmont West Virginian. (Fairmont, West Virginia) February 6, 1907

[4] “An Attorney Steals His Client’s Wife And In Turn Discards His Own.” The Fairmont West Virginian. (Fairmont, West Virginia) February 6, 1907; Stone, Wilbur Fiske. (ed.) The History Of Colorado: Vol. II. The S. J. Clarke Publishing Company. Chicago, Illinois. (1918): 260-262.

[5] “Capitalist Plan Reservoir.” The Irrigation Age. Vol. XXI, No. 9. (July 1906): 274.

[6] Davey, Arthur. The British Pro-Boers 1877-1902. Tafelberg Publishers. Cape Town, South Africa. (1978): 120.

[7] The Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove.

[8] Stone, Wilbur Fiske. (ed.) The History Of Colorado. Vol. II. The S. J. Clarke Publishing Company. Chicago, Illinois. (1918): 260-262.

[9] “Newspaper Misrepresentation.” The Lamp. Vol. III, No. 25 (August 15, 1896): 13-14.

[10] “Loot Of Egyptian Tombs Declined By Jordan.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) August 5, 1905.

[11] H. “Reviews: De Profundis, or the Breaking and Making of a Man.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. III, No. 10. (October, 1905): 332-225.

[12] (Susan Smith) [National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; Roll #: 14; Volume #: Roll 0014 – Certificates: 15882-16588, 14 Jun 1906-20 Jun 1906.]

[13] “An Attorney Steals His Client’s Wife And In Turn Discards His Own.” The Fairmont West Virginian (Fairmont, West Virginia) February 6, 1907.

[14] “Bryan’s Daughter Got Out.” The Goodland Republic and Goodland News. (Goodland, Kansas) August 11, 1905; “‘Bill’ Is Grandad.” The Daily Independent (Hutchinson, Kansas) November 17, 1905; “Bryan Has A Grandson.” The Minneapolis Journal. (Minneapolis, Minnesota.) November 18, 1905; “Mrs. Leavitt Writes A Play.” The Western Advocate (Mankato, Kansas) April 20, 1906.

[15] “Persons Of Interest.” Harper’s Bazar. Vol. XLII, No. 11 (November 1911): 1248-1249.

[16] “An Attorney Steals His Client’s Wife And In Turn Discards His Own.” The Fairmont West Virginian (Fairmont, West Virginia) February 6, 1907.

[17] “An Attorney Steals His Client’s Wife And In Turn Discards His Own.” The Fairmont West Virginian (Fairmont, West Virginia) February 6, 1907.

[18] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove As a Will of Real and Personal Property; Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York, First Department Jun 27, 1941; 28 N.Y.S.2d 571 (N.Y. App. Div. 1941)

[19] “Business Opportunities.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) December 25, 1905; “Capitalist Plan Reservoir.” The Irrigation Age Vol. XXI, No. 9. (July, 1906): 274; In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove As a Will of Real and Personal Property; Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York, First Department Jun 27, 1941; 28 N.Y.S.2d 571 (N.Y. App. Div. 1941)

[20] National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; Roll #: 14; Volume #: Roll 0014-Certificates:15882-16588, 14 Jun 1906-20 June 1906.

[21] “Horse Races At Denver.” The Salt Lake Tribune. (Salt Lake City, Utah) June 17, 1906; “Rune Denver Derby Fast” The Salt Lake Herald (Salt Lake City, Utah) June 17, 1906.

[22] “An Attorney Steals His Client’s Wife And In Turn Discards His Own.” The Fairmont West Virginian (Fairmont, West Virginia) February 6, 1907.

[23] T. “The Hair Line Of Duty” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. IV, No. 1 (July 1906): 27-34.

[24] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove As a Will of Real and Personal Property; Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York, First Department Jun 27, 1941; 28 N.Y.S.2d 571 (N.Y. App. Div. 1941)

[25] “Social Calendar For The Week.” The Weekly Gazette (Colorado Springs, Colorado) July 12, 1906..

[26] “Served Tea On Yacht.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York) July 22, 1906.

[27] “An Attorney Steals His Client’s Wife And In Turn Discards His Own.” The Fairmont West Virginian (Fairmont, West Virginia) February 6, 1907.

[28] Washburne, Marion Foster. “Women Of The Great West: Colorado.” Harper’s Bazar. Vol. XL, No. 5 (May 1906): 404-407.

[29] “An Attorney Steals His Client’s Wife And In Turn Discards His Own.” The Fairmont West Virginian (Fairmont, West Virginia) February 6, 1907.

[30] “State Democratic Convention.” The Windsor Beacon. (Windsor, Colorado) August 25, 1906.

[31] “An Attorney Steals His Client’s Wife And In Turn Discards His Own.” The Fairmont West Virginian (Fairmont, West Virginia) February 6, 1907.

[32] “Bryan To The Rescue.” The Delta Independent (Delta, Colorado) October 19, 1906.

[33] “Why Bryan Refused To Speak In Denver.” The Larimer County Independent (Fort Collins, Colorado) October 24, 1906.

[34] Johnston, Frances Benjamin, photographer. Three portraits of William Jennings Bryan at the Grand Hotel, Paris, all three-quarter length: 1 seated, facing front; 2 seated, facing left; and 3 standing, facing front. , 1905. ?. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/96512124/.

[35] “An Attorney Steals His Client’s Wife And In Turn Discards His Own.” The Fairmont West Virginian (Fairmont, West Virginia) February 6, 1907.

[36] Mitchell, Henry Bedinger. Meditation. Quarterly Book Department, New York, New York. (1906.)

[37] T. “On The Screen Of Time.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XII, No. 4. (April 1915): 361-368.

[38] “An Attorney Steals His Client’s Wife And In Turn Discards His Own.” The Fairmont West Virginian (Fairmont, West Virginia) February 6, 1907.

[39] “An Attorney Steals His Client’s Wife And In Turn Discards His Own.” The Fairmont West Virginian (Fairmont, West Virginia) February 6, 1907.

[40] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove As a Will of Real and Personal Property; Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York, First Department Jun 27, 1941; 28 N.Y.S.2d 571 (N.Y. App. Div. 1941)

[41] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove As a Will of Real and Personal Property; Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York, First Department Jun 27, 1941; 28 N.Y.S.2d 571 (N.Y. App. Div. 1941)

[42] In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Ernest Hargrove As a Will of Real and Personal Property; Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York, First Department Jun 27, 1941; 28 N.Y.S.2d 571 (N.Y. App. Div. 1941)

[43] C.C. Clark. “Ernest Temple Hargrove. Resident. 1908-1939: In Memoriam.” The Parish of the Chapel of the Comforter. 10 Horatio Street, New York.

[44] “‘Ghost Of Noble’s Son Had Taste For Rum.” The Spokane Press (Spokane, Washington) September 3, 1909. “’Ghosts’ In New York Church.” The Dakota Farmer’s Leader. (Canton, S.D.) November 12, 1909.

[45] Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. “Hotel Marlton” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/7316b760-dd37-0131-acc8-58d385a7bbd0.