Having left the American Legation in Constantinople in the capable hands of Lloyd C. Griscom on December 21, 1899, Oscar Straus did not feel any particular need for hurrying home to America.[1] He even made a few stops in Europe along the way. When the papers announced his arrival Vienna, however, he received a note requesting an appointment from a man whom he had read much about. So on December 28, 1899, a meeting was arranged.[2]

Oscar S. Straus (Source: Wiki)

Straus, born in Bavaria in 1850, was one of the most successful Jews in America.[3] His family had something of a history within the worlds of business and politics. His great-grandfather, Jacob Lazar, was one of the deputies to the Sanhedrin convened by Napoleon in 1806.[4] His father, Lazarus Straus, took part in the Revolutions of 1848, and moved the family to America, landing in Philadelphia in the Spring of 1852.[5] He received excellent business training in the Straus family crockery-importing concern at 42 Warren Street, New York City, as such, this Legation was conducted like an office with regular hours. Straus’s two older brothers, Isidor (a former member of Congress,) and Nathan (in addition to their philanthropic work,) were the newest owners of the Macy & Co. department stores.[6] Straus received excellent business training in the Straus family crockery-importing concern at 42 Warren Street, New York City, and ran the American Legation like an office with regular hours. (Oscar’s two older brothers, Isidor and Nathan, would become the owners of Macy & Co. department stores in the following year.)[7]

In 1887 Straus became the first Jewish U.S. minister to Turkey. Straus quickly set to work persuading Sultan Abdul Hamid II to re-open several schools which had been closed in the Ottoman Empire. His most recent success was the successful petition on behalf of the American Colporteur missionaries whose agents were arrested, and their Bibles confiscated. Straus took the matter up with Kamil Pasha (the Grand Vizier) and the Sultan. He pointed out that the Bible had passed the censorship so there should be no objection to its sale. He also reminded the Kamil Pasha that the sale could only be stopped by a breach of their treaty amity and commerce with the Americans. “If Turkey wished to violate that treaty flagrantly,” said Straus, “he would immediately advise his government of this serious breach in our relationship and await instructions.” The Ottomans saw his point of view. A Vizierial degree was secured for the American missionaries.[8] An envoy’s success depended on whether or not he was persona grata to the Sultan, and Straus had accomplished a great deal on his first mission. Abdul Hamid was once asked whether he objected to the United States having sent a Jew. “Not at all,” he replied. “I’m delighted to receive one. In my mind there’s no difference between a Jew and a Christian. Both are infidels.” [9]

In November 1887 Baron Maurice de Hirsch arrived in Constantinople.[10] He was in the city to adjust some financial differences with the Ottomans; his railway, “The Orient Express,” connecting Constantinople with European cities, was nearly complete. Straus helped find an arbitrator for the negotiations between Hirsch and the Sultan. As Straus would say: “The Turkish Government was hard-pressed for funds—its chronic condition.”[11] Through this encounter Straus and Hirsch developed a friendship. Hirsch and his wife Clara had recently lost their child; they declined official invitations but dined with Straus and his wife, Sarah. Hirsch told Straus that during his lifetime he wanted to devote his fortune to benevolent causes. His philanthropy up to that point was mainly bestowed in Russia, but he was desirous of doing something for the Russians who, because of Russian oppression, were emigrating to America. Hirsch wanted to enable them to reestablish themselves. In the coming years Straus would use his connections in New York to assist Hirsch with his philanthropic endeavors. [12]

When the election of 1888 resulted in the Republican nominee, Benjamin Harrison, defeating incumbent Democratic President, Grover Cleveland, Straus tendered his resignation to the new President upon his taking office, as was customary for heads of missions when a change in the administration occurred.

Just before leaving his post in June 1889, Straus dined with the Sultan, as he often did during his stay. The Sultan was especially gracious and unreserved that day and expressed regret at his leaving. Having learned of the great loss of lives caused by the Johnstown flood, the Sultan wished Straus to transmit two hundred pounds to be used for relief work.[13] After the Straus’s boarded the steamer to Varna, a royal caïque came alongside their ship. One of the Sultan’s aides came on board to present to Sarah Straus the highest order, The Grand Cordon of the Chefekat, with the special request of His Majesty that she accept it as “a token of his esteem and regard.” Regulations prohibited Straus from accepting such honors, but this did not apply to his wife. Sarah graciously accepted the Sultan’s parting gift.

When Straus returned to America, he seldom went to Washington. During that time he was occupied with writing two books. He did not, of course, rely on his pen for a living, for he would not have survived long if he had. Writing history, the aristocracy of literature, required long and patient investigation, and yielded meager return. It was, nevertheless, a fascinating avocation for Straus. His Roger Williams, the Pioneer of Religious Liberty, was published in 1894, and The Development of Religious Liberty in the United States, in 1896.[14] By the end of the 1890s Straus found himself gravitating back into the world of politics, having been impressed with what he viewed as electoral reform, especially in the large American cities. The Bosses of the two big parties were “invisible powers” who dictated the nominations.

“Primaries were primaries in name only,” thought Straus, being conducted only to strengthen the power of the Bosses. In Chicago Ralph M. Easley launched a campaign to reform the primaries and organized a political committee called the Civic Federation. In the presidential election of 1896 Straus, formerly a Democrat, voted for the Republican McKinley.[15] Having joined the Republican fold, his reward was a second mission to the Ottoman capital.[16]

~

Theodor Herzl (Source: Wiki)

Straus found his companion an attractive man, a little above medium height, with coal-black beard and hair, and very dark, expressive eyes. If he had to guess, his companion, Theodore Herzl, was a man of about forty years of age—but a man full of energy, and almost beaming with idealism. Herzl, the leader of the Zionist movement, was man of the world, and did not at all give the impression of being the “religious fanatic,” that Straus was lead to believe.

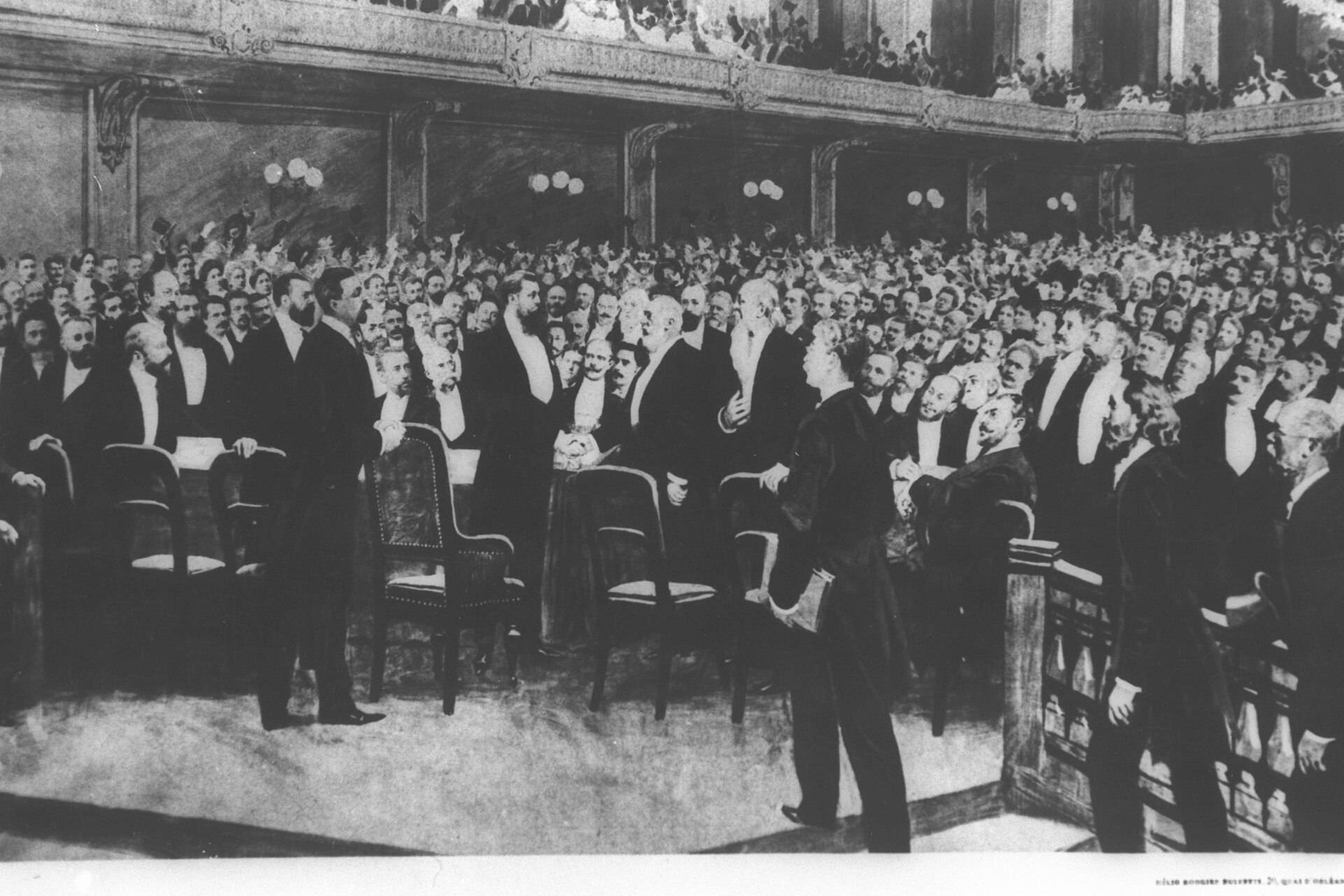

First Zionist Congress (Source: Wiki)

The Zionist movement, founded it 1897, was the greatest attempt to reconquer Palestine in Jewish history. No such effort had been seriously attempted since the Bar Kokhba Revolt in 133, when the Jews squared off against Hadrian’s Romans. Herzl was no warrior, however, not in the traditional sense at least. He was an Austrian playwright, and member of the staff of the Neue Freie Presse. “He was a man of striking personal beauty,” it was said, “towering like Saul over the bulk of his brethren with a long black beard and glowing eyes and the face of the old Assyrian Kings on the bas-reliefs.” He had as courtly manner, was a fascinating conversationalist, and exercised an almost magnetic effect upon everyone with whom he came into contact “from Emperors down to the poor Jews.” In 1894, the Jews of Vienna were in the throes of an outburst of Anti-Semitism, owing to the Dreyfus Affair, and Herzl was outraged by the attempt to treat “even the cultured Jew as a pariah.” The Dreyfus Affair revealed “the true position of the Jew, even in the land of liberty, equality, and fraternity.” So Herzl wrote a book, The Jewish State (1896,) in. which he appealed to the Jews of the world to emigrate en masse to some chosen center of colonization. It did not necessarily have to be Palestine (though that was the ideal,) and even Argentina was floated around as a potential future State for the diasporic Jews. With the publication of the book, Herzl considered his work to be finished. (He was a writer, not a man of action.) In 1897 he presided over the First Zionist Congress in Basel. From that moment, an “awakening began.” Israel Zangwill writes:

A National Fund was also established for the purpose of acquiring land in Palestine, but its total today would probably hardly suffice to purchase a few thousand acres. There has, however, long existed in Jewry an institution called the Jewish Colonization Association, or, for short, the I.C.A. with a capital of ten million pounds, founded by […] Baron de Hirsch for the gradual transfer of the Jews of Russia to some land of refuge. As the petty colonies created by this organization in a dozen different parts of the earth showed not the faintest sign of ever evolving into the necessary haven […] Dr. Herzl’s personal magnetism was, however, a greater asset than even ten millions, and by its exercise upon the leading personages of Europe, he all but reached the goal he had set himself.[17]

Herzl obtained an invitation from Grand Duke Friedrich von Baden (a relative of the German Kaiser, Wilhelm II) who was interested learning more about the Zionist movement. Herzl successfully aroused the Grand Duke’s enthusiasm for the Zionist cause during the meeting, and the Grand Duke subsequently spoke with the Kaiser about Zionism in October 1898 (just before the latter’s journey to Turkey.) It was said that the Kaiser was prepared to assume protectorate powers over the new state should the Zionist succeed, and was amenable to receiving a Zionist deputation in Jerusalem so he could explore the possibility further. Already in 1888, the mighty Deutsche Bank had landed a railway concession in Turkey, and in 1890 the first trade agreement between the German Empire and the Sublime Porte was signed, initiating a process that culminated in December 1899, when the notorious agreement on the building of the Baghdad Railway was concluded. In this drive of German imperialism into the Near East, the Zionists saw an opportunity that was not to be missed.[18]

After some minutes of small talk, Straus and Herzl were speaking intimately.

“You have a reputation of being indiscreet, Dr. Herzl,” said Straus. “I do not blame you for your carelessness, for in so great a matter individuals cannot be protected. Being an official, I am neither for nor against Zionism, but I will be frank—you cannot obtain Palestine. The Greek and Roman churches will not permit it.”

“I took the matter up with the Kaiser Some months before, and I am led to believe that he is not in any way opposed to Zionism—nor to the returning of the Jews to Palestine,” said Herzl. “Zionism, or, rather, the colonization of oppressed Jews, has been developing in my mind for ten or twelve years.”

“I am not Zionist,” said Straus, “though I do not want to give you the impression that I am in any way opposed to the movement—or disposed carelessly to ignore the solemn aspirations which the deeply religious members of my race have prayerfully nurtured in sorrow and suffering through the ages.”

“Has the Sultan ever spoken with you about the subject?” asked Herzl.

“He has not,” said Straus, “as you no doubt understand, it is not an American question, and does not, in any way, come under my jurisdiction.”

They then spoke of the condition brought about through the agitation of Zionism, and the immigration of hundreds of Jews without means into Palestine (where there was not yet any industry that would enable them to make a living.)

“I appreciate that,” said Herzl, “and I am doing everything in my power to prevent such immigration until a permit for a chartered company with sufficient capital has been obtained from the Sultan. I am in correspondence with an official of the Porte for the securing of such a permit.”

“It might be best if you to go to Constantinople yourself,” said Straus, “and personally take up such negotiations.” Straus paused for a moment. “Mr. Herzl, I trust I have your word of honor, that you will say nothing in the open about our interview.”[19]

“Yes, of course.”

“Have you considered Mesopotamia as a more suitable place for the colonization of the Jews than Palestine,” said Straus. “It was the original home of Abraham and his progenitors, is sparsely settled, and if the ancient canals were reopened that country, it could support several million people.” It was substantially what Straus had written a year earlier in a letter to Secretary of State, John Hay.

“I am somewhat familiar with this idea,” said Herzl, “as well as with Professor Haupt’s pamphlet, and a scheme for the colonization of Cyprus. It is perhaps well to have more than one plan—if one did not serve as an outlet for emigration another might.”

~

The idea for a Mesopotamian homeland for the Jews had its origins with Paul Haupt, a well-known specialist in Assyriology and Hebrew who came to America from Göttingen in the early 1880s. There he established a school of classical Oriental Studies at Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, Maryland,) where he was a Professor of Semitic Languages. Among his students was Cyrus Adler, the first man to earn a doctorate in Semitic Language in the United States. Straus had met Haupt one night late in 1891, at a meeting of the Oriental Club in the home of Judge Sulzeberger. The subsequent discussions lasted until near midnight, when Haupt mentioned that he would like to discuss a subject which interested him greatly.

“I, in common with the whole civilized world, have been aroused by the deplorable condition of the Jews in Russia,” said Haupt, “and by the inevitable expulsion from their homes, which is imminent. I have tried to think out the most feasible plan of relief, and that relief lay in Mesopotamia.”

Haupt then produced a manuscript titled: “About The Settlement Of Russian Jews In The Euphrates And Tigris Areas; A suggestion.”[20] “It occurs to me that the proximity of Russia to Mesopotamia would make emigration to that country quicker, easier and cheaper. It is obvious to me, as indeed I am sure it is to you, that what ancient engineers could do is not beyond the power of the moderns, and could even be improved upon. If accomplished, a new territory would be opened which could accommodate tens of millions of people, feeding them in abundance and leaving a surplus for magnificent prosperity!”

“And how is this idea to be utilized?” the others asked Haupt.

“The first thing in order is to print the book, and then to place it judiciously where it will do the most good.”

Straus gave a copy of the book to Baron de Hirsch, but he had already committed himself to Argentina. Adler, for his part, sent a copy, along with a letter, to Herzl in 1897 (just before the First Zionist Congress.) Adler wrote:

Recognizing the fact that more than half of the Jews of the world are now living in countries in which they are regarded as aliens and subjected to most degrading political, social and economic restrictions, I have become convinced that in the next half century a series of very considerable migrations will be rendered necessary […] Various organizations are now engaged in colonization in Palestine and Argentine and these I think should be advised to proceed along the lines they have hitherto followed.

I do not think that a larger percentage of immigration to Palestine should now be encouraged as I feel sure that the country is not able to absorb people rapidly, and besides it would probably raise such opposition on the part of orthodox Christians, as to bring about expulsion of such as are already settled there. Mesopotamia offers the greatest facilities. Besides it has more than once been the home of the children of Israel, where they acquired the discipline and rehabilitation which enabled them to reconstruct their nationality. Both religious sentiment and Biblical precedent would favor the repetition of this plan.

There are many practicable reasons for it rather than a settlement in Palestine which would encounter opposition at the start and prevent colonization from strengthening itself sufficiently to acquire power and permanency to build up and maintain itself. A large part of the lands belong to the Turkish Crown and could be purchased directly from the Sultan. It would be to his interest to have a strong, thrifty, and aggressive population settled there. A sine qua non in the case of all persons settling in any part of the Ottoman Dominions should be their willingness to give up their previous subjection or citizenship. In making these suggestions I wish you would understand that I am speaking only for myself and for a few of my friends, some, I may add, of distinguished political and diplomatic experience, a conference with whom suggested this communication […]

On the other hand, there are Jews in this country of much influence who would be glad to see some extensive plan of colonization in the east established and they are not without hope that eventually an independent state might grow up. All of this should be left to the slow operation of time, but it may well be aided by intelligent and statesmanlike action. Should the conference see fit to entertain the notion of colonizing either in Syria or Mesopotamia, I should be glad to know of it and I may be able to put you in the way of some useful suggestions. I have no desire to appear in this matter and you can if you wish make any of these suggestions on your own initiative. On the other hand, I have not the slightest objection to the use of my name. I am living in the country of my birth, am sincerely attached to it, and feel neither the desire nor need to change it. But I cannot forget the fact that more than half of the men of my faith and blood are being subjected to a daily mental torture which in the end will have results more horrible than death. That they should leave the countries in which they are persecuted becomes a necessity. That they should turn to the East is natural. That their brethren in more favored lands should guide and assist them is but a duty. That they may have many hardships I can well believe. But it is better to perish in a noble struggle than to live a life of servitude.[21]

~

At the conclusion of their discussion, Straus and Herzl separated as friends. Straus promised to write Herzl and tip him off to useful news by using as a confidential signature “Mesopotamicus.” Herzl then wrote a letter to Adler, requesting a copy of Haupt’s pamphlet which he seemingly never received:

I spoke yesterday with an American Jew who lives in Constantin a man who occupies an official position and to whom I promise to name him. He suggested I should turn to you, that you are t man in America with whom I should be in touch. He aroused my interest also in the Mesopotamian project which I should like to study now. There is supposed to be a remarkable pamphlet on this subject, which did not appear in trade, and is in your possession. Would you send it to me?[22]

SOURCES:

[1] “About Prominent Persons.” The World. (New York, New York) December 22, 1899.

[2] Straus, Oscar Solomon. Under Four Administrations. Houghton Mifflin. Boston, Massachusetts. (1922): 156-159; Bein, Alex. Theodore Herzl: A Biography. The Jewish Publication Society Of America. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1940): 391; Weisgal, Meyer Wolfe. Theodor Herzl: A Memorial. Zionist Organization Of America. New York, New York. (1929): 166.

[3] Adler, Cyrus. “Oscar S. Straus: A Biographical Sketch.” The American Jewish Yearbook. Vol. XXIX. (1928): 145-155; Harris, James F. “Rethinking the Categories of the German Revolution of 1848: The Emergence of Popular Conservatism in Bavaria.” Central European History. Vol. XXV, No. 2 (1992): 123–148.

[4] Johnston, Charles. “The New Secretary of Commerce and Labor.” Harper’s Weekly. Vol. L, No. 2604. (November 17, 1906): 1647, 1651; Adler, Cyrus. “Oscar S. Straus: A Biographical Sketch.” The American Jewish Yearbook. Vol. XXIX. (1928): 145-155; Newman, Aubrey. “Napoleon and The Jews.” European Judaism: A Journal for the New Europe. Vol. II, No. 2 (Winter 1967): 25-32.

[5] Johnston, Charles. “The New Secretary of Commerce and Labor.” Harper’s Weekly. Vol. L, No. 2604. (November 17, 1906): 1647, 1651; Adler, Cyrus. “Oscar S. Straus: A Biographical Sketch.” The American Jewish Yearbook. Vol. XXIX. (1928): 145-155.

[6] Beecher, Henry Ward. Beecher: Christian Philosopher, Pulpit Orator, Patriot and Philanthropist. Belford, Clarke, & Company. Chicago, Illinois. (1887): 61.

[7] “The Progress of The World.” The American Review of Reviews. Vol. XXIII, No. 1. (January 1901): 3-23; Van Norman, Louis E. “Ambassador Straus, The Man for the Emergency in Turkey.” The American Review of Reviews. Vol. XXXIX, No. 6. (June 1909): 685-688.

[8] Johnston, Charles. “The New Secretary of Commerce and Labor.” Harper’s Weekly. Vol. L, No. 2604. (November 17, 1906): 1647, 1651.

[9] Griscom, Lloyd C. Diplomatically Speaking. The Literary Guild of America. New York, New York. (1940): 136.

[10] [Arrived November 28, 1887] “Baron Hirsch at Constantinople.” The Nottingham Evening Post. (Nottingham, England.) November 29, 1887.

[11] Straus, Oscar Solomon. Under Four Administrations. Houghton Mifflin. Boston, Massachusetts. (1922): 93.

[12] Straus, Oscar Solomon. Under Four Administrations. Houghton Mifflin. Boston, Massachusetts. (1922): 92-96.

[13] The Johnstown Flood occurred on Friday, May 31, 1889, after the failure of the South Fork Dam, in the town of Johnstown, Pennsylvania.

[14] Straus, Oscar Solomon. Religious Liberty In The United States. Philip Cowen. New York, New York. (1896.)

[15] Straus, Oscar Solomon. Under Four Administrations. Houghton Mifflin. Boston, Massachusetts. (1922): 102, 120, 123-128.

[16] “The Progress Of The World.” The American Review Of Reviews. Vol. XXIII, No. 1. (January 1901): 3-23; Van Norman, Louis E. “Ambassador Straus, The Man For The Emergency In Turkey.” The American Review Of Reviews. Vol. XXXIX, No. 6. (June 1909): 685-688.

[17] Zangwill, Israel. “Zionism And Territorialism.” The Fortnightly Review. Vol. LXXXVI, No. 600 (April 1910): 646-655.

[18] Polkehn, Klaus. “Zionism and Kaiser Wilhelm.” The Journal of Palestine Studies. Vol. IV, No. 2 (Winter 1975): 76- 90.

[19] Weisgal, Meyer Wolfe. Theodor Herzl: A Memorial. Zionist Organization Of America. New York, New York. (1929): 166.

[20] Perlmann, Moshe. “Paul Haupt And The Mesopotamian Project, 1892-1914.” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society. Vol. XLVII, No. 3 (March 1958): 154-175.

[21] Perlmann, Moshe. “Paul Haupt And The Mesopotamian Project, 1892-1914.” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society. Vol. XLVII, No. 3 (March 1958): 154-175.]

[22] Straus, Oscar Solomon. Under Four Administrations. Houghton Mifflin. Boston, Massachusetts. (1922): 156-159; de Haas, Jacob. Theodor Herzl: A Biographical Study. Vol. I. The Leonard Company. Chicago, Illinois. (1927): 308-309.