In the previous post, we left off in 1891 with the rise of Theosophy in California, the Creation of the Pacific Coast Committee Of The Theosophical Society, the relationship between the Theosophists and the Nationalists, and the Lecture Bureau Scheme. We pick up two years later in San Francisco, the Headquarters of the Pacific Coast Committee. By 1893, San Francisco had two Branches of the Theosophical Society. The first was the Golden Gate T.S., led by Edward “Ned” Burroughs Rambo (1845-1897.) This Branch was “interested mainly in the devotional aspects of Theosophy.” The second Branch (established in 1891) was the San Francisco T.S., led by Dr. Jerome A. Anderson (1847-1903.)[1] This group was “what might be called the scientific Branch, giving its attention to research and investigation and study of the laws of nature.”[2]

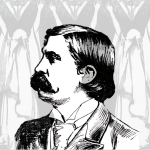

EDWARD BURROUGHS RAMBO: PRESIDENT OF THE GOLDEN GATE T.S.

E.B. Rambo.[3]

Edward “Ned” Burroughs Rambo (1845-1897) was described as a “steady, calm, and judicious Theosophist.” Though his friends on West Coast sometimes thought him over careful, and backward, he was a counter balance to the members who might “fly off too far on a tangent.” Rambo was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on April 5, 1845, to parents of “old Indiana Quaker stock.” He was educated in a public school, but had to delay his studies when he was thirteen as his father’s death caused a disruption in family life. He was adopted by an uncle back East, and with stability restored, he was able to earn enough money to continue his education at the “Quaker School” in Providence, Rhode Island (presumably the Moses Brown School.) In 1870, he married Mary Amelia Taylor. They had three children, Alice (b. 1871,) Martha (b. 1875,) and William (b. 1876.)[4] For some time they lived in Chicago, and it was there where he went into the Presbyterian Church, “but that was not satisfying to his soul.” In 1882 Rambo was made the Pacific Coast manager of the Winchester Repeating Arms Co. (manufacturer of the famous Winchester repeating rifle.) He and his family subsequently moved to a flat in San Francisco.[5] It was said that Rambo was “as mild-mannered a man as ever sent a ship load of rifles and cartridges to the discontented minority of a Spanish American Republic.”[6] Operations flourished under Rambo, who moved the office from their Battery Street location to new rooms at 418 Market Street (the city’s main thoroughfare,) just a block away from the Palace Hotel. An active Freemason of high degree, Rambo became associated with the Lodges of San Francisco. (Yerba Buena Lodge of Perfection and the Yerba Buena Chapter of the Rose Croix.) Neither Rambo nor Mary were fond of city life, so they purchased a 30-acre farm in Santa Clara Valley (thirty miles south of San Francisco) as a retreat.

In 1886, Sarah Winchester, the wealthy widow of William Winchester (founder of the Winchester Repeating Arms Co.) asked Rambo for advice on purchasing property in California. Rambo insisted that she visit his home in Santa Clara. The place had become his “new haven,” he told her, adding that he thought that she would like it, too. Winchester agreed, so Rambo, acting as her guide, took her on a carriage tour of his home and Santa Clara Valley. During this tour Rambo took her to see a 45-acre property a half-a-mile away from his farmhouse, which Winchester subsequently purchased (with the assistance of Rambo.) The home on the property was small, but she planned on making additions. Winchester next hired Rambo to be the foreman of her farm (though he continued to work as manager of the Market Street offices,) so the Rambos lived half the year in Santa Clara. Sarah Winchester would make baffling architectural decisions when designing her home, which was in various states of construction in perpetuity while she was alive. It was said the “Nightmare Castle” was haunted by the spirits of the victims of Winchester guns, and that Sarah would die the day the house was completed. Doors and hallways which lead to nowhere were a fixture of the house, allegedly to trick the spirits who haunted her.[7] It was, perhaps, a fanciful legend, but other nearby buildings erected at the time most certainly had “ghostly” origins.

It was around this time that Senator Leland Stanford and his wife, Jane Stanford began constructing Leland Stanford Jr. University, or “Stanford University” as it would become more popularly known. In 1884, young Leland Stanford Jr. (the namesake of the school) died in Italy while touring Europe with his parents. After reading the service for the dead, Leland Stanford Sr. told the chaplain:

I have just had a strange experience, and if you will be kind enough to come into the next room I would like to tell you about it and ask for your advice […] Just after my son died I sank into a chair and for a time became unconscious. When I was in this state my son, who seemed to be standing beside me said, “Father I want you to build a university for the benefit of poor young men, so that they can have the same advantages the rich have,” after which he left me. Now, tell me what you think of that, and if you think I ought to do it.[8]

It was in this manner that the idea of founding Stanford University originated. Jane Stanford often told her husband (and several very close friends) that she frequently saw their dead son in the spirit, and could, “in her innermost soul and mind, believe that he was talking to her.” Jane also claimed to have witnessed her son’s ghost shortly after his death. She saw him sitting on his pony at the Stanford residence in Palo Alto. For some time after that, the pony would be equipped with saddle and harness, in preparation for the regular morning rides for the ghost of her son, just as it had been when he was still alive.[9] Rambo himself dabbled in Spiritualism at the time:

In 1886 from studying the character of a friend he was led to investigate spiritualism, and gave it attention for some years but with no satisfaction, but it made an alteration in his mode of life so that he became a vegetarian and a strict abstainer from alcohol and narcotics; it also led him to believe in continuity if not in immortality. In 1886 he went to a camp-meeting of Spiritualists at Oakland […] and there a speaker showed that Reincarnation is the only just and true doctrine of immortality, and he left that meeting convinced of the fact of reincarnation.[10]

Mary Rambo died in 1888, and still not finding the spiritual answers he desired, he read Theosophical books and became convinced of their truth. He joined the Society on March 3, 1889.[11] “The central idea of our religion or philosophy is the universal brotherhood of man,” Rambo would say, “that all mankind is one family.”[12]

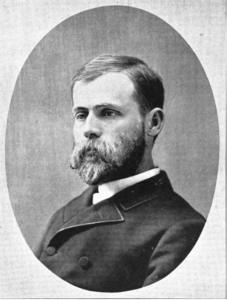

JEROME ANDERSON: PRESIDENT OF SAN FRANCISCO T.S.

Jerome A. Anderson.[13]

Jerome A. Anderson was a “spare, thoughtful looking man, very earnest and serious in manner and a thorough believer in the purely scientific nature of his researches in the domain or psychic forces.”[14] Born in Randolph County, Indiana, on July 25, 1847, Anderson’s father, W. G. Anderson, was a pioneer settler of Kansas, having come from North Carolina with his parents as a child. Education was important to Anderson’s family. (Five generations in Anderson’s direct line were school teachers.) His early education was received in the public schools of Kansas, and he later attended a private seminary at Neosho Falls, Kansas. Anderson would state, however, that “he grew up with almost no educational advantages, being far more familiar with Indian war-whoops than with their civilized congener, the college ‘yell.’” His biography in The Path states:

His thirst for knowledge was insatiable, and by tallow lamps or the flame of hickory bark he spent hours poring over books in the evening after the rest of the family had retired. It is a legend of his childhood that he never learned to read, being found by accident to possess this ability when four years old. Indeed, all his mental acquirements have been more in the nature of reviewing old and familiar studies than in the pursuing of new.

Anderson was described as “a pure-minded boy of religious inclinations,” who was affiliated with the Presbyterian Church while still young. However, Anderson would “[abandon] the Christian faith, becoming first a Universalist, then an Agnostic, then a semi-Spiritualist” in subsequent years. When the Civil War broke out, Anderson, at the age of sixteen, became a substitute for his father in the 16th Kansas Cavalry State Troops. After the war, in 1868, Anderson began the study of medicine under the preceptorship of Dr. J. W. Driscoll, of Neosho Falls, with whom he studied three years. (To finance his medical training, he was a teacher in the public schools.) In 1871 Anderson entered the Medical College of Ohio (Cincinnati, Ohio) where he remained for one year. In 1872 he moved to San Francisco, and entered the new Medical Department of the University of California. He made his home at 3783 Twentieth Street, atop a hill near the old Mission which overlooked the city.[15] He received the degree of Doctor of medicine in 1873, being in the first class which graduated from that institution. He soon entered in the practice of medicine, opening an office is in the Odd Fellows Building. Anderson was among the foremost of San Francisco physicians, and wrote many medical brochures, the most notable publication being “Nutrition Of The Fetus,” based upon original experiments and “fairly marking an epoch in embryological physiology.” He was also a member of the State Medical Society of California, of the County Medical Society of San Francisco, Fellow of the San Francisco Obstetrical and Gynecological Society, and former President of the Alumni Association of the Medical Department of the University of California. “At a time […] when all the honors of his profession lay apparently within his grasp,” The Path states, “[Anderson] deliberately put them aside—retaining only his Fellowship in the San Francisco Gynecological Society—and entered upon that Theosophic work which still employs his best efforts.”

While “doubtfully floundering among spiritualistic phenomena,” Anderson’s friend, William A. Boyce, sent him a review of The Occult World published in The Sacramento Record-Union. This led to Anderson purchasing the work, and later Isis Unveiled. Boyce then sent Anderson the first issue of The Path.[16] This brought him into correspondence with Judge, whose influenced him to join the Theosophical Society as a member-at-large in April 1887.[17] He would soon join the Golden Gate Branch (San Francisco,) and serve as its president for some time. In 1891 Anderson left the Golden Gate Branch and became one of the founders of the San Francisco T.S.[18] He would state:

We differ from materialistic scientists in this, that we accept facts wherever we find them, and whatever their nature. The materialistic investigator recognizes as fact only that which concerns palpable matter, and rejects all—or nearly all—phenomena that have their origin in the subtler forces of the universe. The idea that matter was produced and arranged in its various forms by a force that came from nowhere is simply nonsense. Yet that is the so-called scientific postulate. In nature nothing is lying around loose in the void. Everything is governed by laws, and those laws are the manifestations of Universal Consciousness. That consciousness, or any part of it, can no more be lost or destroyed than can matter itself. The ego, the soul, is a part of that Consciousness, which is the motive energy of the universe, and when the matter animated by it dies, changes its molecular arrangement, the ego remains coherent and modified by its experiences. It finds another material form in which to manifest itself—and that is reincarnation, a demonstrable scientific fact. All matter is acted upon by consciousness or susceptible of modifications by it. Thought is consciousness, not a mere mechanical motion of brain molecules. The brain is but the medium through which the force manifests itself, and keeps the record of its operation. The brain is the dynamo and thought is the electric energy that is put into active operation by the machine. Thought acts upon the material form of the bruin and the modifications of the molecular and atomic arrangement of the brain react and make impressions upon the consciousness. In their failure to recognize the correlation of forces, the materialistic are un-scientific.[19]

One of the co-founders of the San Francisco T.S. was George P. Keeney (1862-1922.)[20] Keeney, who joined the Theosophical Society in 1889, was an editor, scholar, writer, a skilled orator, and one of the founders of the San Francisco Branch.[21] He was regarded by many as an authority on “Asiatic questions.”[22] (He wrote such Theosophical entries as “The Astral Light,” and a series on “Consciousness.”)[23]

That summer (1891) Anderson became the founder-editor of a literary monthly called The New Californian (which was effectively a Theosophical journal.) “Theosophy, a term by which more than one effort to reform the ethical and spiritual beliefs of men has been known,” Anderson states in the first issue. “[It] is the Message which the Orient sends to the Occident.”[24] Anderson remained the editor of The New Californian during its first year. By February 1892, W.Q. Judge declared that the magazine had become “avowedly a Theosophical Journal.”[25] An unspecified illness, however, forced Anderson to stop work on the magazine. Louise A. Off (assisted by Marie Carhart,) took over the editorial responsibilities for The New Californian and subsequently relocated its offices to Los Angeles.[26] Anderson returned to editorial work with The Pacific Theosophist, a San Francisco-based Theosophical journal which ran from 1891 to 1898.[27] His first major Theosophical literary work was Reincarnation: A Study Of The Human Soul (1893.)[28]

PACIFIC COAST LECTURERS

The rise in Theosophy in California owed its success in no small part to the Theosophical Lecture Bureau. Two names involved with this scheme stand out in particular, Abbott Beals Clarke (1865-1948,) and Allen Griffiths (1853-1920.)[29] The first named, Clarke, was a member from Point Loma California who joined in March 1889.[30] He was also a founding member of the Nationalist Club in that city. In his own words we find the fate of that group, and its connection with Theosophy:

All the Nationalist clubs in the West traced their origin, the first definite cause for their existence, to the kindly mention and praise of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward in The Key to Theosophy […] This first drew our attention to the book Looking Backward, which we purchased and widely circulated […] The Nationalist Clubs in California sprang up all at once in towns and cities where there were branches, as we called them, of the Theosophical Society. We all knew that it was a spontaneous action of Fellows of the Theosophical Society that organized the Nationalist Clubs. Four Theosophists formed the nucleus and obtained directions from Boston for the formation of a Nationalist Club [in San Diego.] Twenty or thirty members of the Theosophical Society invited their friends, and we formed a club which met weekly. Judge Sidney Thomas was elected president and I secretary. We were also respectively president and secretary of the Theosophical Society. Within two or three months we had over 600 members, including the elite of the intellectuals of the city. Thus it would seem that the Theosophists felt that they had found a suitable channel for giving practical expression to their faith, while Bellamy had unexpectedly found a considerable number of sincere, ardent workers for his cause […]

In 1892 I spent the summer in Los Angeles in newspaper and Theosophical work. There was no Nationalist Club in Los Angeles at that time.[31] In 1892, in the fall, I went to San Francisco where were located at that time the headquarters of the Theosophical Society on the Pacific coast . Here I was associate editor of The Pacific Theosophist and traveling lecturer, frequently visiting all the cities in that part of California. There were no Nationalist Clubs to be found . In some places there were Socialist societies , but the mention or insistence upon Universal Brotherhood brought hisses and sometimes denunciation. The whole spirit of their meetings was different, usually very different, from that in the Nationalist Clubs. During the time from 1888 to 1900 I became acquainted with most of the leading Socialists on the Pacific coast. Some of them became my personal friends, but the character of their work was so different from that of the Nationalist Clubs that I have put off finishing this letter all these weeks lest I seem to be prejudiced or unkind […] I am told that the Socialists now claim the Nationalist Clubs. Such a claim would have been indignantly repudiated by more than nine- tenths of our Nationalist Club membership . The Socialists were advocating “Class Consciousness” (of the working classes,) as against the Plutocrats and all of the Bourgeoisie who did not actually sympathize with the Proletarians. The Nationalist Clubs were Universal Brotherhood clubs. Please emphasize this. All “classes” (a taboo word) were well represented in our Club.[32]

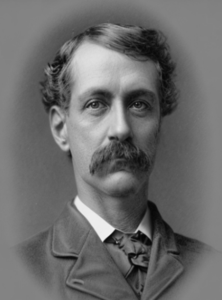

Allen Griffiths.[33]

Allen Griffiths (1853-1920) was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on February 8, 1853.[34] He had “piercing black eyes,” and some thought “a very aggressive manner,” but this was “simply the vast energy” of the man. In 1864 his parents “crossed the plains in a horse team to Oregon.” When he was fifteen he joined a revivalist church, and ended up in San Francisco. The church asked him to take a letter of demit, but he refused, stating “his views had altered.” He was subsequently expelled from the church.[35] In 1877 he graduated as a dentist, and in 1880 he married Angelina “Angie” Matilda Gellerson (1852-1895) of Maine.[36] She was a business woman of energy, who had an office in the Crocker Building.[37] They would have two children, Foster (b. 1881,) and Adelaide (b. 1887.)[38] It was around this time that he began investigating Spiritualism, and though he found there was something to it, he found the system as a whole unsatisfying. He was introduced to Sinnett’s The Occult World, and he “felt a thrill on hearing the title, and got the book.” The book re-enforced a belief system which he intuitively felt to be true (e.g. belief is reincarnation, karma, and the Masters.) He joined the Golden Gate T.S. on December 18, 1887.[39] (Angie would join in 1890.)[40] On March 15, 1892, he was appointed by the Branches of the Coast as their lecturer.[41]

PRISON WORK

The Prison Work effort began in the Winter of 1894, when the Theosophists of San Francisco wanted to teach Theosophy in California prisons. Anderson, President of the Pacific Coast Executive Committee stated at the time:

We [had] been trying for over a year to secure admittance, but for one reason or another we were always disappointed. Finally one of the Directors of the prison told us that the proper way for us to do it, would be to send a formal application for permission to give religious instruction to prisoners through the chaplain. We did not proceed without some definite reason. Our society from time to time in the past twelve months has received letters from intelligent prisoners urging us to visit and instruct them.

The Board of Directors at San Quentin met on Saturday, February 10, and upon the recommendation of Reverend August Drahms, (the Lombrosian prison chaplain of San Quentin Penitentiary,) they refused to grant the Theosophical Society an application to give occasional religious instructions to the prisoners.[42] On Monday, February 12, the Pacific Coast Executive met to consider the actions of the Directors. Anderson, Rambo, Keeney, Clarke, and Griffiths were all present. With them was Veronica “Vera” Stanislaus Beane (1842-1924,) another Theosophist on the Committee.[43] She was the Secretary of the San Francisco Branch, and President of the Women’s Christian Union.[44] Born in New York, but long-time California resident, she was described as an “elderly, but attractive,” woman with “a magnetic presence,” who was mentally “calm and clear.”[45] She lived with her husband, Colonel Beane, at The Recamier (an elegant boarding-house at 632 Post Street.)[46] Rambo “considered the rejection of the application very unjust,” and broadly hinted that Christianity had a “cinch” on the prison “entirely opposed to a spirit of fair play and to the religious equality established by the national Constitution.” Anderson stated:

I shall communicate with the Governor, and we hope that he will reverse the bigoted recommendation of the San Quentin chaplain. Theosophy is not alone involved in the determination of this question. It remains to be seen as a broad proposition whether the religious welfare of several hundred convicts is to be exclusively given over to Rev. Mr. Drahms in spite of the desire of some of the prisoners to seek religious instruction at other hands.[47]

The Theosophists would eventually prevail. Rambo would personally visit San Quentin once a month, where nearly 600 men would turn out to hear him speak. “All the men loved and respected him,” it was said, “and he has brought a gleam of light and hope into the lives of many of them.”[48] It was said:

A number of the prisoners have not only been reading this literature, but studying and calling the attention of their fellow prisoners to it. The result of this has been the formation of a class which meets regularly for the study of Theosophy. One of the most earnest of this class, hearing that his friends contemplated circulating a petition for his pardon, refused to allow them to proceed, stating that he preferred to serve his time out because he had an opportunity of imparting a knowledge of Theosophy, which had done so much for himself, to those with whom his lot had been cast. This he considered his Karma and duty to do.[49]

By the end of 1894 Paul Bunker, a Theosophist from San Francisco, would also gain permission for the delivery of Theosophical lectures in Folsom Prison.[50] (The work was along a similar line of that in San Quentin.)[51] “The wardens of both prisons assert that a decided change for the better is noticeable in the prisoners’ discipline and deportment since the Theosophists began giving lectures there, and they encourage that work by affording every facility for its continuance and success.”[52]

WORK AMONG THE SAILORS

Though Theosophy was not a “religion” in the orthodox sense, it may as well have been (as evidenced with the prison work.) There was even something of “missionary work,” though the Theosophists were careful not to call it that. This was called propaganda work (the word had yet to develop its negative connotation) for the League of Theosophical Workers. For this line of work, we find Albert Hatten Pile (1854-1896,) who joined the Theosophical Society in May 1893.[53] He was the son of William A. Pile, a former Missouri Congressman, Minister to Venezuela, and Governor of New Mexico. When Pile’s family moved to California, both father and son became the owners of valuable mines.[54] Pile followed his father into politics, working as a Deputy Comptroller in San Francisco.[55] Not long after, he became a member of the Esoteric Section. He was a member of San Francisco’s League of Theosophical Workers (No. 5) and was involved with distributing leaflets to the sailors on the waterfront.[56]

Albert H. Pile.[57]

The scheme worked like this: In San Francisco they divided the seawall (waterfront where the ships load and unload) into three sections. One section was taken up every Sunday morning, and every ship that they could reach was visited. They would engage the sailors in conversation, draw their attention in a pleasant manner to the serious side of life (tact had to be exercised in this,) offer them some Theosophical leaflets, such as “Epitome Of Theosophy,” “Necessity For Reincarnation,” and “Theosophy As A Guide In Life,” which were invariably accepted with thanks. They would depart with a cordial invitation for them to attend meetings, make use of the Theosophical library while in port, and give them a card announcing the time and place of all their meeting, with the aims and objects of the Society printed upon it. Sometimes their conversations were prolonged, but no formal addresses were given. “Short and sweet” was their motto. If any questions were asked, they would answer it briefly, drawing their attention, at the same time, to the leaflets they had received. In this way the entire seawall was covered every month, visiting some of the ships two or three times. Many thousands of leaflets were distributed. While this was being done, the Theosophists would attend the Sailors’ Union, supplying their library with Theosophical books (except the most expensive ones,) magazines, pamphlets, etc.[58]

In this way they gained the sailor’s good will, and had the use of their hall (which had a seating capacity for several hundred) free for their lectures on the first Sunday afternoon in the month. In return for the use of the hall, the Theosophists advertised the meeting in The Seamen’s Journal (paying regular rates,) which was read by every Union sailor, “thus attracting their attention through their own ‘Bible’ to Theosophy.” Another line of work along these lines was carried on for months by one the Branch’s “silent” workers who was engaged in shipping. “When clearance papers [were] given, he [addressed] a polite note to the Captain, accompanied by a neat little package of Theosophical literature,” which proved very effective.[59]

DEATH OF L. A. OFF

In October 1894, Louise A. Off, the tireless Theosophist of Los Angeles, contracted tuberculosis. For three months “her hold on life had been but the merest thread.” By December she was “unable to lie down, and her sufferings were great.” When the end came, it was peaceful as she quietly fell asleep in the early dawn on January 6, 1895.[60] Those who were with her in the last said that she was fully conscious, and that she did not suffer any pain. She recognized her mother and said, “Oh, I did not know that it was so easy to die.”[61] Her remains were cremated the following day at Rosedale Cemetery. “The beautiful and impressive ceremony of the [Theosophical Society] was repeated in open air.”[62] In addition to her work for the Theosophical Society, the Nationalist movement, and literary output, Off was one of the individuals who pioneered “ghost hunting” in California. The year before her death, Off was one of the founding members of the American Society For Psychical Research in California.[63]

REORGANIZATION

At the Boston Convention of 1895, the American Section of the Theosophical Society split from its parent organization in India. Rambo, a familiar figure at the annual Conventions was instrumental in the reorganization of the Society.[64] A warm friend and steadfast supporter of W.Q. Judge, Keeney made this statement just before the Convention:

Here Mrs. Besant would leave the impression adroitly that whatever powers Mr. Judge possesses their exercise by him is purely automatic. Why, what escape is there from such an accusation. Even Madame Blavatsky herself would have been made the victim of such an insinuation.

On the other hand, any true occultist can see that Mr. Judge could be subject to the volition of the masters without losing the conscious principle and becoming a mere automaton. His mind would be simply subordinated, and operating in perfectly conscious harmony with the will of the mahatma influencing him. But see what [Besant] says: “A friend told her that Mr. Judge did not receive messages from the masters.” Who is this friend? It looks very much as if some subtle influence emanating from India was behind this to injure American Theosophy. It has always been the desire of the Hindoo Brahmins to maintain the intellectual supremacy on this planet, and their influence is now being exerted to hurt a grand American brotherhood which has been erected upon a foundation of pure ethics.

I do not question the honesty of Annie Besant—the Annie Besant who stood up in the English courts for a principle; the Annie Besant who led the London mob; the Annie Besant who organized the London matchgirls; the Annie Besant who has done more for the London masses than any other woman! No; all I can say is that she is being made the instrument of the inimical Hindoo hierarchy.

Why, Mr. Judge was for a quarter of a century a pupil Madame Blavatsky. He is a man of untiring energy and has done more for Theosophy than any other living man. He has at last come out, now that he has been forced to, and openly claims to be in occult communication with the Masters. Annie Besant has herself said that she saw “the Master” in Mr. Judge. He does not claim to be “the agent,” but merely “an agent” of the Masters.[65]

It was during this time, that Griffiths introduced the Theosophical Prison Work to Boston.[66] On May 2, 1895, he addressed the Boston Branch and spoke on prison work. The subject created great interest, and Fanny Field Hering took it upon herself to secure an opening in the Charleston State Prison Griffiths to lecture. Three days later (May 5, 1895) Griffiths spoke on “Karma And Reincarnation” before and enthusiastic crowd of nearly 600 inmates.[67] “The countenance of many a one lighted up as he grasped the idea that though his present life may have proved a failure, he would have yet other lives and chances wherein to redeem himself.”[68] The lecture was such a success, that similar plans were made for Griffiths to lecture in New York at Sing Sing and Blackwell’s Island.[69]

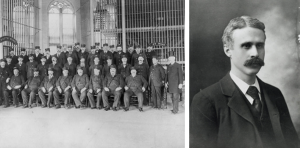

(Left) Guards in Charlestown State Prison (Boston, Massachusetts) c.1896.

(Right) Josiah Quincy. Mayor of Boston from 1896-1900.

Within a year, Elizabeth M. Gibbons and Elvira Ivers, two members of the Beacon T.S. (Boston,) picked up where Griffiths left off.[70] They had already created a Theosophical group called the “Bell Ringers,” a scheme that involved distributing leaflets on the streets and in the stores, and talking with whoever could be found to listen to them as they went from house to house (“whence their name of Bell Ringers.”) The Bell Riggers were composed largely of the women members of the Boston Branch who wanted to do Theosophical work but could not find an “output for their pent up energy.”[71] After meeting some success, Gibbons and Ivers, “unaided, save by letters of introduction,” succeeded in interesting Mayor Josiah Quincy (who was already favorably impressed by the Theosophical movement) in the Prison Work. Through Mayor Quincy, the women reached the ears of the Superintendent and Chaplain of the House of Correction in South Boston, who allowed them to speak there on certain Sundays.[72]

JUDGE’S STATUE

Judge died within a year of the American Section declaring its autonomy. By peculiar coincidence, Keeney was somewhat responsible for the bust of William Q. Judge that was unveiled at the Theosophical Convention in April 1896. Keeney had arranged for the sculptor, August Lindholm, to model Judge, and on March 21, 1896, he started for Judge’s home to get his permission. Along the way he learned that Judge had died. Judge had earlier consented to having a death mask taken, however, and from that mask, Lindstrom was able to make the bust.[73]

(Left) “Death Mask Of William Quan Judge.”[74] (Right) “Bust Of Late W.Q. Judge.”[75]

POLITICS

Theosophical politics would be more pronounced in California. Anderson, one of the freeholders of San Francisco, became affiliated with the People’s (Populist Party,) in 1895, a party which had notes of the Nationalist Club. It was Anderson’s belief that the city should “run like any other great corporation,” by “making somebody responsible.” In the proposed charter produced by the freeholders by the spring of 1895, the mayor’s office was greatly strengthened, acquiring appointive power over several municipal department heads, including four (parks, police, fire, health) and election commissioners appointed at that time by the governor. The freeholders also enabled the city to acquire hated private utilities and to incur bonded indebtedness for extraordinary expenses for such a purpose. In 1896, Anderson would run as a candidate for mayor of San Francisco for the People’s Party.[76] At the same time, he published the influential book, Karma: A Study Of The Law Of Cause And Effect (1896.)[77]

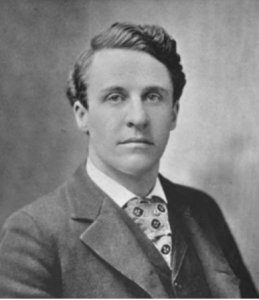

George P. Keeney.[78]

Keeney and Pile, were involved in politics on the national stage. It was said that Keeney was one of the rare men who knew how to organize, and carry victory with them. His work was marked by rare sagacity, and a broad, comprehensive grasp of complex systems. In the 1890s, he was quite successful in unifying the National and North Atlantic factions of the American Silver Parties, and in 1894 was one of the founding members of the Bimetallic Party.[79] It was said that the complete overthrow of the Southern Pacific Railroad’s choice of mayor for San Francisco was thwarted, in large part, to Keeney’s “splendid generalship, excellent tact, and indefatigable efforts.” He was a factor in William Jennings Bryan’s first campaign for the Presidency in 1896, heading the Free Silver Club which was the basis of the candidate’s platform.[80] Unsurprisingly, he “made himself greatly feared by the plutocracy of the East.”[81] Pile was the Secretary of the National Committee of the Silver Party.[82] (Pile identified as a “Silver Republican,” but believed that Bryan would carry California by a majority.)[83]

On July 20, 1896, Keeney and Pile were in St. Louis, Missouri, attending the National Convention of the Silver Party.[84] During the Convention, the Executive Committee of the Silver Party’s National Committee placed A.H. Pile in charge of the accounts and records of the committee. Keeney, meanwhile, was appointed a member of the Democratic National Campaign Committee.[85] On July 28, after leaving the Silver Party Convention, Keeney, Pile, and several other members of the Silver Party left for another Party Convention in Washington, D.C. There they secured a headquarters for the National Party Committee at 1420 New York Avenue. It was where Senator Stewart of Nevada (one of the publishers of the journal, The Silver Knight) had his editorial sanctum.[86] Pile, however, was missing. He was last seen on August 4, 1896, attending a Democratic barbecue in Falls Church, Virginia. Pile returned to D.C. that evening, with two friends, who parted ways with him at the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and Seventh Street. They returned to their hotel, the Ebbitt House at Thirteenth Street and Avenue G, but Pile never returned, and there was no trace of his whereabouts.[87]

On the morning of August 10, a crowd of boys swimming in the Potomac River found Pile’s body floating near the Aqueduct Bridge. The police were notified, and a patrol wagon rushed the corpse to the morgue at the sixth precinct. His body (which would not be identified until sometime later,) could not have been in the water for more than two days, but within that span of time, the face had bloated, and the hands had decomposed. His silver watch had stopped at 3:40. Curiously, there were no shoes on the body.[88] (The scene was reminiscent of the death of the Theosophist, E.D. Walker.) During the examination of the body, Morgue Keeper Schoenberger failed to reveal any marks of violence, nor anything to suggest foul play. As the body was discovered a short distance, from the several gambling resorts (on the Virginia shore of the Potomac,) that were “frequented by the worst element,” it was speculated that Pile was “enticed into one of those dens, robbed, and thrown in the river.” The condition of his pockets suggested otherwise, for none of his notebook, or papers had been disturbed, and the silver watch piece had not been taken. The police could hardly imagine a thief would steal an old pair of shoes and leave everything else. Precinct Detective Burrows thought that, perhaps, due to the excessive heat, Pile had gone to the river, removed his shoes in order to cool off, and accidentally drowned. A search for the shoes was conducted along the shores, for if they were found, they would “go a long way toward solving the mystery.” They were never located, nor was Detective Burrows able to find any evidence to suggest that Pile had visited any of the gambling dens.[89]

On August 11, 1896, James D. Finch, and J.M Devine (both of whom were connected with the Silver Committee,) called at the morgue to identify Pile’s body. They said that Pile appeared drunk when he was last seen, but when, or how, he got up the river remained a mystery. When the body had been identified, Detective Rhodes went to Pile’s hotel room to take charge of his effects. Among the items retrieved was a locked, tin, cash-box, on which was pasted a piece of paper that read: “Forward unopened to William Q. Judge, 144 Madison Avenue. New York City. A. H. Pile, San Francisco, April 4, 1895.”[90]

Burcham Harding (acting President of the Theosophical Society) upon learning of the news of Pile’s death, and the subsequent discovery of the box, wrote a letter to the authorities at Washington, requesting them to send the box to 144 Madison. He added in his letters a request, that if that could not be accommodated, to at least hold the box, unopened, until Emil, as executor of Judge’s will, could obtain legal possession of the box. This request was granted. George Coffin (President of the Washington, D.C. Branch) held onto the box until its disposition by the courts.[91] No further communication was received from Pile’s relatives in California, except a telegram from his brother, which stated that, being unsure of the deceased’s identity, he could not defray the funeral expenses. (In the weeks that followed, Coffin would receive further correspondence from Pile’s relatives which explained their reasons why they did not believe that the body to be Pile’s and requested further proofs.)[92] At the request of Keeney, Coffin supervised and conducted the funeral services in the private chapel of Lee’s undertaking establishment. At the conclusion of the ceremony, Pile’s body was carried to the crematory and reduced to ashes.[93]

DEATH OF RAMBO

Throughout 1896 and 1897, Rambo worked with Judge’s successor, Katherine Tingley, to secure the Point Loma location for her occult school/colony called The School For The Revival Of The Lost Mysteries Of Antiquity.[94] A year after Pile’s death, however, Rambo, too, died under mysterious circumstances. Witnesses said that Rambo complained of feeling unwell at his ranch on August 13. Three days later (August 16, 1897,) after riding his bicycle to his work in San Francisco, Rambo collapsed and died. Jerome Anderson, Rambo’s physician, surmised that Rambo had a heart attack after cycling.[95] It circumstances surrounding his death were nearly identical in detail to the death of fellow Theosophist, Soh Kwang-pom, right down to the time of death.

UNIVERSAL BROTHERHOOD

At the time of the Chicago Convention in 1898, when the Universal Brotherhood was established, Anderson, indorsed the action of the Convention, and supported Katherine Tingley.[96] A year later, he published The Evidence For Immortality (1899.)[97] By 1902 Anderson had become disillusioned with Tingley and the Universal Brotherhood.[98] He asserted that he had letters to show that Tingley “was a woman lacking even the first rudiments of a good education,” and “accused her of forging mental messages supposed to come from the spirit world.”[99] In the end, he joined the Adyar Theosophists. “The Olcott faction has two societies this city, and I have joined one of them,” Anderson said. “I’m a Theosophist pure and simple, and am done with Madame Tingley for good.”[100] A year later, on Christmas day 1903, Anderson died at his San Francisco home from Cerebral Oedema.[101]

Abbott B. Clarke would go on to live out his days in San Diego, and be one of the men who popularized avocados in America, by introducing them to the Point Loma Homestead, and championing their cultivation.[102] Griffiths, a widower since 1895, would have a sadder ending, dying at 70 in Alameda, California in 1920.[103] His remains were found in his apartment (1375 Versailes Avenue) on the Fourth of July, only after other renters in the apartment noticed that a light had been burning in his room overnight.[104]

SOURCES:

[1] “Mirror Of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. VIII, No. 3. (June 1893): 88-96.

[2] Kelly, Allen. “Cult Of The Theosophists.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) January 8, 1893.

[3] Hargrove, E.T. “The Screen Of Time.” Theosophy. Vol. XII, No. 7 (October 1897): 375-380.

[4] Rambo, Beverly Nelson; Beatty, Ronald S. The Rambo Family: Vol. II. (Second Edition.) Author House. Bloomington, Indiana. (2010): 340.

[5] Ignoffo, Mary Jo. Captive Of The Labyrinth: Sarah L. Winchester Heiress To The Rifle Fortune. University Of Missouri Press. Columbia, Missouri. (2010): 90-91.

[6] Kelly, Allen. “Cult Of The Theosophists.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) January 8, 1893.

[7] “The huge building has been reared on an estate of thirty acres. It has no sense and no design. It has 144 rooms, 2,000 doors, at least 10,000 windows, and 150,000 painted window panes. Inside are miles of twisting corridors; to attempt to pass through them without reading the arrows painted on the walls would mean to get hopelessly lost. There are doors which open on to blank walls and on to the ceiling; there are grotesque galleries in the middle of the rooms which are built on varying levels; there are windows on the chimneys and on the staircases, which latter rise suddenly to crazy heights and resemble narrow mountain paths fit for goats[…] Although a Spiritualist, [Sarah L. Winchester] was obsessed by the fear of death. In the belief that she would die on the day the building operations ceased, she kept on erecting new wings year after year.” [“Nightmare Castle.” Light. Vol. LIV, No. 2,816. (December 27, 1934): 798.]

[8] “Leland Stanford’s Vision.” The Essex County Herald. (Guildhall, Vermont) March 10, 1905.

[9] “Aged Mrs. Stanford Feared Death From Poison After Recent Attempt Here Against Her Life.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) March 2, 1905.

[10] “Faces of Friends: E.B. Rambo.” The Path. Vol. VII, No. 11 (February 1893): 354-356.

[11] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4542. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Edward B. Rambo. )

[12] Kelly, Allen. “Cult Of The Theosophists.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) January 8, 1893.

[13] Anderson, Jerome A. Reincarnation: A Study Of The Human Soul. The Lotus Publishing Company. San Francisco, California. (1893): Frontispiece.

[14] Kelly, Allen. “Cult Of The Theosophists.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) January 8, 1893.

[15] “Theosophists Disturbed By A Serious Revolt In Their Ranks.” The San Francisco Chronicle. (San Francisco, California) March 25, 1902.

[16] In Anderson’s biography in The Path, it states that the man who gave him The Occult World and The Path was the managing editor of The Morning Call. The managing-editor at the time was William A. Boyce. [Cramer, James Prentiss. “The Press Of San Francisco.” The Californian. Vol. I, No. 6 (May 1893): 519-540.]

[17] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4161. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Jerome A. Anderson. (4/10/1887)

[18] The Bay Of San Francisco: The Metropolis Of The Pacific Coast And Its Suburban Cities. Vol. II. Lewis Publishing Co. Chicago, Illinois. (1892): 78-79; “Mirror Of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. X, No. 2. (May 1895): 62-72; Kelly, Allen. “Cult Of The Theosophists.” The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, California) January 8, 1893.

[19] Kelly, Allen. “Cult Of The Theosophists.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) January 8, 1893.

[20] [(1862-1922) “California Death Index, 1905-1939”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QK91-RRHW : Sat Mar 09 03:50:23 UTC 2024), Entry for George P Keeney, 27 12 1922.]

[21] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 5594. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) George P. Keeney. (11/26/89); “Will Defend Mr. Judge.” The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco, California) April 7, 1895.

[22] “George P. Keeney Is Honored At Funeral.” The Los Angeles Times. (Los Angeles) December 31, 1922.

[23] Keeney, George P. “The Astral Light.” The New Californian. Vol. I, No. 3 (August 1891): 84-89; Keeney, George P. “Consciousness Pt. I.” The New Californian. Vol. I, No. 10 (March-April 1892): 304-307; Keeney, George P. “Consciousness Pt. II.” The New Californian. Vol. I, No. 11 (May 1892): 331-336.

[24] Anderson, Jerome A. “From Orient To Occident.” The New Californian. Vol. I, No. 1 (June 1891): 7-16.

[25] “Literary Notes.” The Path. Vol. VII, No. 1 (April 1892): 26-29.

[26] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3580. (Website file: 1B:1885-1890) Louise A. Off. (1/12/1886); “The New Californian.” The Los Angeles Herald. (Los Angeles, California.) February 27, 1893; “American Theosophical Serials.” Notes And Queries And Historic Magazine. Vol. XVIII, No. 3 (March 1900): 81-86.

[27] “Faces Of Friends: Jerome A. Anderson” The Path. Vol. VIII, No. 1 (April 1893): 8-10; “Astral Photography.” The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco, California) September 8, 1896.

[28] Anderson, Jerome A. Reincarnation: A Study Of The Human Soul. The Lotus Publishing Company. San Francisco, California. (1893.)

[29] [CLARK]: “California Death Index, 1940-1997,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VPZ9-MGR : 26 November 2014), Abbott Beals Clark, 18 Sep 1948; Department of Public Health Services, Sacramento.. [GRIFFITH]: “Deaths.” The San Francisco Chronicle. (San Francisco, California) July 9, 1920.

[30] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4861. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Abbot B. Clark. [Point Loma. San Diego, California. (3/17/1889.]

[31] Arthur E. Morgan writes: “Since Cyrus Willard was secretary of the First Nationalist Club, and later correspondent with Theosophists over the country; the increase or decrease of mutual interests was somewhat in his hands. He writes of his own course during this period: ‘Men like Abbott Clark looked to me to keep them advised by mail, and I did. I sized up Mason Green quickly and felt sorry for Bellamy, and it turned out just as I knew it would. The People’s party politicians were no better.’ It was in 1889 and 1890 that the great development of Nationalist Clubs occurred under the stimulus of the Theosophists. With the discontinuance of the Theosophist controlled Nationalist magazine, and the starting of the New Nation under Bellamy’s personal direction, these clubs disappeared almost as suddenly as they had arisen.” [Morgan, Arthur E. Edward Bellamy. Columbia University Press. New York, New York. (1944): 275.]

[32] Morgan, Arthur E. Edward Bellamy. Columbia University Press. New York, New York. (1944): 266-267, 275.

[33] “Faces Of Friends: Allen Griffiths.” The Path. Vol. VIII, No. 2. (May 1893): 40-41.

[34] “Deaths.” The San Francisco Chronicle. (San Francisco, California) July 9, 1920.

[35] “Faces Of Friends: Allen Griffiths.” The Path. Vol. VIII, No. 2. (May 1893): 40-41.

[36] “Deaths Reported.” The Oakland Enquirer. (Oakland, California) January 21, 1895.

[37] “A Theosophical Row.” The San Francisco Chronicle. (San Francisco, California.) March 10, 1894.

[38] Glenn, Thomas Allen. The Pedigree Of William Griffith, John Griffith And Griffith Griffiths. Private Printing. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1905): 51.

[39] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4249. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Allen Griffiths. (Golden Gate) 12/28/87.

[40] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 6047. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Angie M. Griffiths [Golden Gate. (6/12/1890.)

[41] “Faces Of Friends: Allen Griffiths.” The Path. Vol. VIII, No. 2. (May 1893): 40-41.

[42] Justice, Benjamin. “‘A College of Morals’: Educational Reform At San Quentin Prison, 1880-1920.” History Of Education Quarterly. Vol. XL, No. 3 (Autumn 2000): 279-301.

[43] “Death Notices.” The San Francisco Bulletin. (San Francisco, California.) December 17, 1924; “Death Of A Mother.” The Petaluma Morning Courier. (Petaluma, California) December 23, 1924.

[44] “Mirror Of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. VI, No. 12 (March 1892): 410-418.

[45] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4198. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Veronica M. Beane. [Los Angeles T.S. Stockton, California. (10/20/1887.)]; “A Theosophical Row.” The San Francisco Chronicle. (San Francisco, California.) March 10, 1894.

[46] “Rooms And Boarding.” The San Francisco Chronicle. (San Francisco, California.) May 22, 1893; “A Theosophical Row.” The San Francisco Chronicle. (San Francisco, California.) March 10, 1894.

[47] “Theosophists Barred Out.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) February 18, 1894.

[48] J.H.F. “Edward B. Rambo.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. III, No. 4 (August 1897): 49-50.

[49] “Theosophy In San Quentin.” The Pacific Theosophist. Vol. IV, No. 10. (May 1894): 158-159.

[50] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 9750. (website file: 1D:1894-1897) Paul Bunker. [San Francisco T.S. 1682 Valley Street San Francisco California. (6/20/1893)]; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 9755. (website file: 1D:1894-1897) Caroline Hemenway Bunker. [San Francisco T.S. 1682 Valley Street San Francisco California. (6/20/1893.)]

[51] “Prison Propaganda.” The Pacific Theosophist. Vol. V, No. 3 (October 1894): 48.

[52] “Theosophical Prison Work.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) May 3, 1895.

[53] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 9572. (website file: 1D:1894-1897) Albert Hatten Pile. (Fresno, California. 5/5/93.)

[54] “Find a Grave Index,” database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QL7T-FCVC : 14 September 2020), Albert Hatten Pile, ; Burial, , ; citing record ID 178973434, Find a Grave, http://www.findagrave.com.

[55] “Found In The River.” The Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.) August 10, 1896; “Former St. Louisan’s Death.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch (St. Louis, Missouri) August 12, 1896; “Obituary.” The Theosophical News Vol. I, No. 10 (August 24, 1896): 2; “Mirror Of The Movement.” Theosophy. Vol. XI, No. 6 (September 1896): 191-192; [[1860 United States Federal Census] Year: 1860; Census Place: Kansas City, Jackson, Missouri; Roll: M653_625; Page: 42; Family History Library Film: 803625]; [“Pile, William Anderson 1829-1889.” Biographical Directory Of The United States Congress. Accessed July 11, 2021. https://bioguide.congress.gov/search/bio/P000350.]; [Deputy Comptroller) “United States, GenealogyBank Historical Newspaper Obituaries, 1815-2011,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q5QB-NHWB : Fri Mar 15 01:12:30 UTC 2024), Entry for A H Pile, 13 Aug 1896.]

[56] “Notes And Items.” The Pacific Theosophist. Vol. V, No. 1 (August 1894): 12.

[57] “How Did A.H. Pile Come To His Death?” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) August 12, 1896.

[58] E.W. “Among The Sailors.” The Theosophical News. Vol. I, No. 41 (March 29, 1897): 1-2.

[59] Williams, Evan. “How To Work Among Sailors.” The Pacific Theosophist. Vol. VI, No. 12 (March 1897): 45-47.

[60] “Death Record.” The Los Angeles Times. (Los Angeles, California) January 7, 1895; “The Death Of Miss Louise Off.” The Los Angeles Evening Express. (Los Angeles, California) January 10, 1895; “Mirror Of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. IX No. 11 (February 1895): 405-410.

[61] Lloyd, Marguerite S. “Obituary.” The Pacific Theosophist. Vol. V, No. 6 (January 1895): 96.

[62] “News In Brief.” The Los Angeles Herald. (Los Angeles, California) January 9, 1895.

[63] “Spook Investigators.” The Los Angeles Herald. (Los Angeles, California) January 2, 1893.

[64] J.H.F. “Edward B. Rambo.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. III, No. 4 (August 1897): 49-50.

[65] “Will Defend Mr. Judge.” The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco, California) April 7, 1895.

[66] “Boston Prison Work.” The Theosophical News. Vol. I, No. 16. (October 5, 1896): 3.

[67] “Pacific Coast Lecturer’s Movements.” The Pacific Theosophist. Vol. V, No. 10. (June 1895): 169-170.

[68] “Convicts Hear Of Reincarnation.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) May 6, 1895.

[69] “Theosophical Prison Work.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) May 3, 1895.

[70] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 10,262. (website file: 1D: 1894-1897) Elvira L. Ivers [Ames Building, Boston, Massachusetts. Boston T.S. (10/21/1893)]; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 11,869. (website file: 1D: 1894-1897) Elizabeth M. Gibbons [34 Temple Place, Boston, Massachusetts. Boston T.S. (11/1/1894.)]

[71] G.D.A. “The Theosophical Bell Ringers.” The Theosophical News. Vol. I, No. 8. (August 10, 1896): 4.

[72] “Boston Prison Work.” The Theosophical News. Vol. I, No. 16. (October 5, 1896): 3.

[73] “Theosophists In Session.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) April 27, 1896; “W.Q. Judge Changed His Skull’s Shape.” The New York Journal. (New York, New York) May 7, 1896.

[74] “W.Q. Judge Changed His Skull’s Shape.” The New York Journal. (New York, New York) May 7, 1896.

[75] “Theosophists In Session.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) April 27, 1896.

[76] “No Fusion On The Municipal Ticket.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) September 25, 1896; Ethington, Philip J. The Public City: The Political Construction Of Urban Life In San Francisco, 1850-1900. University Of California Press. Berkeley, California. (2001): 388-389.

[77] Anderson, Jerome A. Karma: A Study Of The Law Of Cause And Effect. The Lotus Publishing Company. San Francisco, California. (1896.)

[78] “Notes By The Editor.” The Arena. Vol. VIII, No. 80 (July 1896): 338-553.

[79] Taggart, Harold F. “California And The Silver Question In 1895.” Pacific Historical Review. Vol. VI, No. 3 (September 1937): 249-269.

[80] “George P. Keeney Is Honored At Funeral.” The Los Angeles Times. (Los Angeles) December 31, 1922.

[81] “Notes By The Editor.” The Arena. Vol. VIII, No. 80 (July 1896): 338-553.

[82] “Found In The River.” The Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.) August 10, 1896; “Former St. Louisan’s Death.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch (St. Louis, Missouri) August 12, 1896; “Obituary.” The Theosophical News Vol. I, No. 10 (August 24, 1896): 2; “Mirror Of The Movement.” Theosophy. Vol. XI, No. 6 (September 1896): 191-192; [[1860 United States Federal Census] Year: 1860; Census Place: Kansas City, Jackson, Missouri; Roll: M653_625; Page: 42; Family History Library Film: 803625]; [“Pile, William Anderson 1829-1889.” Biographical Directory Of The United States Congress. Accessed July 11, 2021. https://bioguide.congress.gov/search/bio/P000350.]; [Deputy Comptroller) “United States, GenealogyBank Historical Newspaper Obituaries, 1815-2011,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q5QB-NHWB : Fri Mar 15 01:12:30 UTC 2024), Entry for A H Pile, 13 Aug 1896.]

[83] “Shouting For Bryan.” The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco, California) July 21, 1896.

[84] “Notes By The Editor.” The Arena. Vol. VIII, No. 80. (July 1896): 338-553; “Shouting For Bryan.” The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco, California) July 21, 1896.

[85] “Jones Has ‘Corked’ Bryan.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. (St. Louis, Missouri) July 28, 1896.

[86] Jones Has ‘Corked’ Bryan.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. (St. Louis, Missouri) July 28, 1896; “Strange Death Of A.H. Pyle.” The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco, California) August 11, 1896; “The Dead Man Identified.” The Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.) August 11, 1896.

[87] “The Dead Man Identified.” The Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.) August 11, 1896; “A.H. Pile Found Dead.” The Sun. (New York, New York) August 12, 1896.

[88] “Found In The River.” The Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.) August 10, 1896; “A.H. Pile Found Dead.” The Sun. (New York, New York) August 12, 1896.

[89] “The Dead Man Identified.” The Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.) August 11, 1896; “As To Pile’s Death.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) August 13, 1896.

[90] “Strange Death Of A.H. Pyle.” The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco, California) August 11, 1896; “The Dead Man Identified.” The Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.) August 11, 1896.

[91] “Silver At An Inquest.” The Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.) August 12, 1896; “A.H. Pile Found Dead.” The Sun. (New York, New York) August 12, 1896; “Pile’s Relatives Doubt.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) August 12, 1896; “As To Pile’s Death.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) August 13, 1896.

[92] “Pile’s Relatives Doubt.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) August 12, 1896; “As To Pile’s Death.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) August 13, 1896.

[93] “Funeral Of A.H. Pile.” The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, California) August 12, 1896; “Obituary.” The Theosophical News Vol. I, No. 10 (August 24, 1896): 2; “As To Pile’s Death.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) August 13, 1896.

[94] de Purucker, G. “‘The Finding Of’ Point Loma.” The Eclectic Theosophist. No. 88 (July/August 1985): 6-9.

[95] “Summoned To The Next Life.” The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco, California) August 17, 1897.

[96] “Vengeance On Renegade Theosophists.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) August 21, 1899.

[97] Anderson, Jerome A. The Evidence For Immortality. The Lotus Publishing Company. San Francisco, California. (1899.)

[98] Anderson states: “Judge died within a year after he started the insurrection, but even in that time 140 lodges had been organized in the United States, and the Movement seemed to be sweeping all before it. Then came Mrs. Tingley’s claim to the leadership based on some scraps of writing in Judges personal diary, in which he spoke of her fitness to succeed him, because of her remarkable qualities as a medium. He never formally selected her. She assumed her office and immediately caused another reorganization under the name of the Universal Brotherhood and the adoption of a constitution and by-laws giving her absolute power in all things. All the real and personal property of the Brotherhood was put into her name, and she became to all intents and purposes, not only the head of the order—but the order itself. Now witness what she has done. She stopped the magnificent work of promotion inaugurated by Judge, discouraging workers because of the personal homage which she insisted should be done her. No enthusiasm was possible then. She bought this land at Point Loma and went to live there with a court—such as has never been seen off of a comic opera stage. She did all she could to interest people of wealth in Theosophy, and she invented ways and means that the founders of the order never dreamed of. Some of them were the formation of such non-sensical branches as the Isis League of Music and Drama designed to elevate the stage, the School for the Revival of the Lost Mysteries of Antiquity, and a sort of literary bureau with a name so long that I have forgotten it. She has spent $30,0000 at Point Loma, and with every dollar that has gone into the establishment, she has invented new court regulations. I have seen men and women of wealth, education, and high social position, humble themselves before her in a way that sensible people can hardly conceive of. I stood it myself for a while, I wore long gowns and ridiculous hats in her presence, and tried to take part in the foolish ceremonies with some belief that they might have a meaning. But I knew it meant that pretty soon we would have to crawl into Mrs. Tingley’s presence on all fours. It grew worse with every visit I made, and I finally threw the whole thing up. As an organization Theosophy has gone all to pieces under Mrs. Tingley. Of the 140 prosperous lodges organized by Judge, not more than a dozen exist today, and the only work in the spreading of the truth has been done by Colonel Olcott and his loyal followers. As a physician, I would say that the woman is a megalomaniac suffering from an advanced state of the same disease that affects the German Emperor. I have no doubt that she thinks she is a divine being, but I don’t think so, and I told her my opinion on the subject.” [“Theosophists Disturbed By A Serious Revolt In Their Ranks.” The San Francisco Chronicle. (San Francisco, California) March 25, 1902.]

[99] “Death Of Dr. Jerome Anderson.” The Californian. (Salinas, California) December 28, 1903.

[100] “Arraigns Madam As An Arrogant Dictator.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) March 25, 1902.

[101] Ancestry.com. California, U.S., County Birth, Marriage, and Death Records, 1849-1980 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2017. Original data: California, County Birth, Marriage, and Death Records, 1830-1980. California Department of Public Health, courtesy of www.vitalsearch-worldwide.com. Digital Images.

[102] Clark, Abbott B; Clark, Orange I. “Results Of Pollination And Other Experiments On Avocados At The Orchards Of The Point Loma Homestead.” In Annual Report Of The California Avocado Association: Yearbook For The Years 1925-1926. The California Avocado Association. Los Angeles, California. (1926): 85-94; Popenoe, F. O. “San Diego County Avocado History.” California Avocado Association 1927 Yearbook. Vol. XII. (1927): 41-48.

[103] “Died.” The Oakland Enquirer. (Oakland, California) January 18, 1895.

[104] “Relative Sought Of Dr. Allen Griffiths.” The Oakland Tribune. (Oakland, California) July 5, 1920.