The Airdsmen huddled over the skeleton in the trench.

“Who do ya ‘spose it was?”

It was a balmy day in late July 1886. The “Airdsman,” that is, the workmen in the employ of John Aird & Sons, had been laying a main for the Commercial Gas Company when they made their remarkable discovery. Six feet below the surface, at the intersection of Cannon Street Road and Cable Street, in St. George’s-in-the-East, they found a skeleton with a stake driven through it, and chains lying near the bones.[1]

“Best call for Mr. Aird…”

Gas Company Works.[2]

~

The presence of such an object, quite naturally, caused discussion in the neighborhood. With the aid of some of the older inhabitants (whose memories carried them back three-quarters of a century,) the identity the skeleton was revealed. By common consent, the old-timers declared that the unearthed remains once belonged to the principal character of some tragic occurrences which took place at the close of the year 1811. The story they told was substantially this:

Newspaper sketch of the Marr shop and residence. (Wiki.)

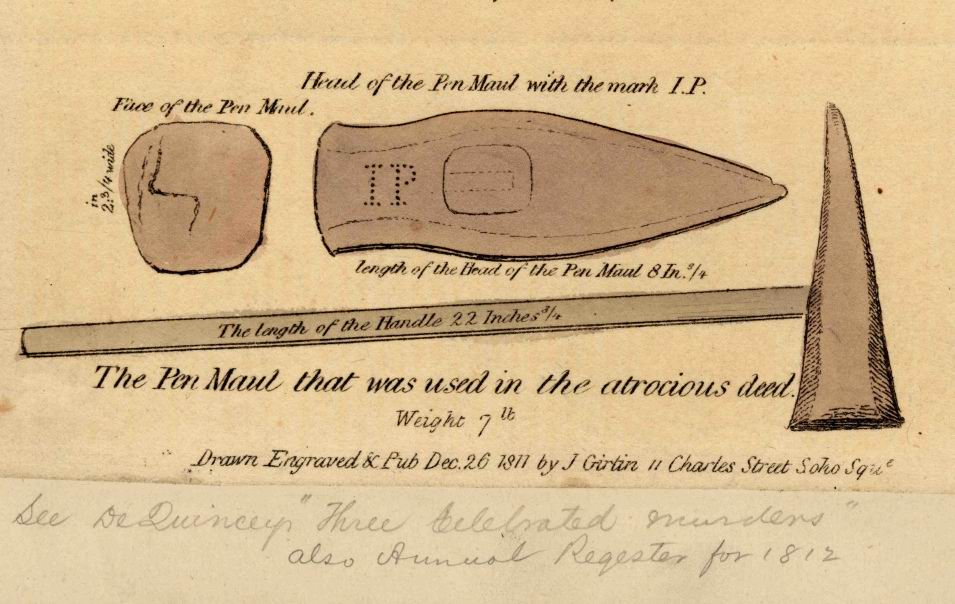

Shortly before midnight on December 8, 1811, the servant of a Mr. Marr (a silk merchant who resided at 29 Ratcliff Highway,) was sent out to purchase some oysters and to pay a bill. She returned twenty minutes later, but was unable to gain admittance to the house. The shutters were closed, the door was fastened, and all the lights were out. With the aid of Mr. Murray, who lived next door, they were able to gain entrance through the back door. When the door was opened, they found a ghastly scene. Mr. Marr was murdered, so too was Mrs. Marr, their infant child (aged fourteen weeks,) and Marr’s fourteen-year-old apprentice, named James Gohen. Nothing was taken from the bouse, for nearly £160 was found on Marr. The murderers left behind a three-foot shipwright’s mallet with a three-pound head, an iron chisel eighteen inches long, and a wooden mallet four inches square. The perpetrators left the house by the back door on to a piece of waste ground belonging to the London Dock Company.

Murder Weapons. (Wiki)

Near midnight, on the night of December 19, 1811, the neighborhood of New Gravel-lane was alarmed by a cry of “Murder” at the King’s Arms Public House. Citizens found a nearly-naked man climbing from a second-floor window with the aid of some sheets knotted together.

Escape of John Turner. (Wiki)

He was a lodger there, and quickly identified as the man named Turner. Earlier that evening, after having gone upstairs to bed, Turner heard a cry, “We shall all be murdered.” This induced him to (cautiously) descend the stairs again. Looking through the glass window of the tap-room, Turner saw a powerful man, six-feet tall, dressed in a shaggy bearskin coat. He was stooping over the body of Mrs. Williamson, the landlady, rifling her pockets. Turner returned to his bedroom and let himself down from the window. It was soon discovered that Mr. Williamson had also been murdered in the cellar, and Mrs. Williamson’s servant girl was lying dead by the side of her mistress. Once again, the vacant piece of land belonging to the Dock Company was used by the murderers to escape.

Postmortem sketch of John Williams, a.k.a. Murphy. (Wiki)

The authorities had strong evidence to apprehend an Irish sailor named John Williams, alias Murphy, who lodged at the Pear Tree Public House kept by Mrs. Vermilye. When conducting their investigation, police discovered that former lodger of the Pear Tree, a ship’s carpenter named John Paterson, had left a chest of tools which the mallet discovered at the first murder scene belonged. The washerwoman of the Pear Tree also testified as to having come into possession a torn, bloody shirt which belonged to Williams.

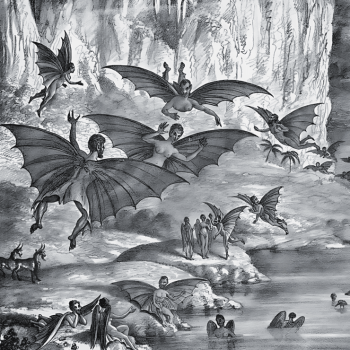

Williams was remanded to Coldbath Fields Prison and sentenced to hang. Williams, however, managed to cheat the hangman. Two days after Christmas his lifeless body was discovered hanging by his handkerchief from the iron grating of his cell. In accordance with the custom of the period the suicide was buried in the dead of night at four crossroads, with a stake driven through his body.

Burial procession of John William. (Wiki)

Self-killing was regarded as a felony under law, and desperate sin in the eyes of the church, and a coroner’s inquest could determine a guilty-verdict of felo de se (a felony against oneself.) A part of the punishment for such a ruling was the denial of a Christian burial. The body, instead, was buried face down at a crossroad with a wooden stake driven through the chest (and in some instances chains for good measure.) This was done to protect the community, as souls of suicides were thought to be “restless and malevolent.” It was believed that staking (and chaining) the corpse to the ground likewise anchored the ghost. As for the crossroads, it was thought that this confused the wraith, and prevented it from returning to the community of the living and inflicting any harm.[3]

Sketch of John Williams’ corpse on the death cart. (Wiki)

The death of Williams did little toward allaying the public panic. A general notion prevailed that the murderer was assisted by accomplices, and two of his friends, Allbrass and Hart, were apprehended; but after several examinations, they were released. The excitement took a long time to subside, but eventually the event faded out of recollection, with nothing to keep the tragedy alive except the memory of the old-timers near St. George’s-in-the-East.[4]

[1] “Discovery Of A Staked Skeleton.” The North-Eastern Daily Gazette. (Middlesbrough, England) July 31, 1886.

[2] “A Gas-Stoking Machine.” The Illustrated London News. (London, England) January 11, 1890.

[3] Lowman, Emma Battell; Tarlow, Sarah. Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse. Springer. Cham, Switzerland. (2018): 101.

[4] Anon. Chronicles Of Crime And Criminals. Beaver Publishing Company. Toronto, Canada. (1895): 40-45.