Lamasery.

David A Curtis, “one of the cleverest reporters on the New York press,” paid a visit to “The Lamasery,” the Theosophical headquarters, on March 20, 1878. It was a large house dedicated to French flats on Eighth Avenue & 47th Street, in the “new” neighborhood of Longacre near the massive carriage factory of Brewster & Co.[1] When Brewster moved their operations there in 1872 the neighborhood became the center of the carriage business in New York. The region became chiefly devoted to equine matters. The trade journals likened it to “Longacre Street” (where London’s the carriage trade was centered.) The square, having no name at the time, was christened Longacre Square by municipal authorities.[2] As for “The Lamasery,” it was Curtis who named it “after the sacred colleges of Thibet, where acolytes are trained in the mysteries and sacred rites of Thibetan theology.”[3]

The nature of Curtis’s visit was found in the pages of the newspaper he brought with him, which gave an “account of the night-walking of the ghost of a defunct night-watchman, along the wharves of a certain district on the East side of the city.” Curtis begged his fellow Theosophists, Madame Blavatsky, Col. Olcott, and W.Q. Judge to investigate. “The police were all agog,” said Curtis. “The inspector of that district has made all preparations to have it seized tonight.”[4] The four Theosophists arrived at the Twenty-First Precinct House (160 East Thirty-Fifth Street) a little after 11 p.m.

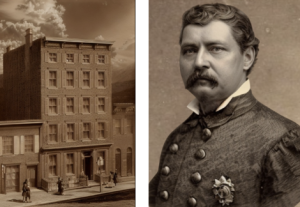

(Left) Twenty-first Precinct building. (Right) Captain Michael J. Murphy.[5]

They were greeted by Capt. Michael J. Murphy, “a man of superior intelligence and experience,” and Tommy “the horse” Gilbride, a “Hibernian,” patrolman, that is, a member of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, who, like so many other Irishmen, filled the ranks of New York City’s Metropolitan Police.[6] Three days earlier many of these Hibernian patrolmen wore the “national green,” and participated in the line of march in honor of St. Patrick, and “renewed their pledges of patriotism and good fellowship,” by “drowning the Shamrock” in honor of Ireland’s patron saint.[7] Gilbride, however, assured the Theosophists (and Capt. Murphy,) that no beer or whiskey had compromised his wits when he encountered the apparition of the night-watchman. Gilbride recounted the story of his encounter with the old watchman Old Shep as he escorted the local press, and a handful of Theosophists, to the spot near the East River piers where he last saw him.

Officers of the Twenty First Precinct in the 1870s.[8]

“I don’t remember the night, but it was the night Kearney was off, maybe two weeks ago, when I was tryin’ me doors coming up First Avenue at the corner of 39th Street.”

Though America’s “aristocracy” lived on the western border of the Twenty-first Precinct, it was common knowledge that on the eastern border, closer to the East River, that patrolmen were fine game for the “young thugs” who terrorized the district. A patrolman’s safety lied in his ability to handle his locust and pistol.[9]

“I was trying a door that had a low handle,” Gilbride continued, “and I was bending down from me left hand, and me right hand on the door, so, when I looked around to me left, for I heard a footstep behind me, and as near to me as the Captain is now, I saw a man standing. At first, not thinking it was Shep at all. I straightened up meself and then saw, sure enough, it was Old Shep I seen! And I wasn’t thinking of him at all, mind you.”

Joseph Shepherd, or “Old Shep” as he was known, was a private night watchmen—a professional caller for people who needed to rise at those “unseemly hours” between nightfall and sunrise. He could be seen shuffling along Third, Second or First Avenue, never quite sober, nor could it be said that he was ever quite positively drunk—he lingered somewhere in between, just as his spirit seemed to be doing in death. It was a morning, about three weeks earlier, when he was found floating, face down, in the river at E. 39th Street. Whether he was murdered or drowned in a bottle first, his cause of death remained a mystery. A week earlier Captain Murphy paid a visit to the haunted pier, and though he did not see the ghost himself, the excitement of the event generated enough talk, that he felt determined to get to the bottom of the mystery. The most unsettled were those who once used “Old Shep’s” services—if he still roamed about with his lantern, he may just, from force of habit, come calling on them once more. These former patrons, naturally, would prefer it if “Old Shep” did not

“Are you sure it was him?” asked one of the reporter.

“Of course I am. I saw him as plain as I see you now.”

“Why didn’t you speak to him?”

“I hadn’t the time. All of a sudden, he wasn’t there. He didn’t walk out of the place he was in. He didn’t move one way or the other. He just wasn’t there when I looked for him the second time, and that was the second after I saw him first, while I was rapping for Foley. Whether he went up, or whether he went down, I don’t know…but he just…disappeared—right away.

“Were you frightened?”

“No,” Gilbride said, “I wasn’t afraid of him. What should I have been afraid of him for? He had nothing against me. It’s not true, as some of the boys tell, that I’d like to have killed meself running away, or that I fell down in a dead faint, or that I drank a whole pail of water before I came to me senses. I’d have spoken with him if he had stopped. If he wouldn’t have got away out of me hands in that queer way. I’d have spoke to him about his being around when by rights he had no business to be.”

“Was Old Shep guilty of disorderly conduct?” the reporters asked.

“Well…no…well now, I ain’t so sure it was a disorderly conduct of him, but I wouldn’t have been afraid to try and bring him in if I could!”

“Was the apparition how you imagined a ghost to appear?”

“Oh! No, no. He’s not the first ghost I’ve seen! I’ve seen two at the Morgue—standing right up. I was outside the street. It was the time of the blowing up of the Staten Island ferry-boat.”

“Well, did you speak to them?”

“No, I said nothing to them…nor them to me. I just went along me business.

“Had you heard talk of Old Shep coming back?”

“Well, I think maybe I did, but I paid no attention.

“Did you know he was dead?”

“Of course I knew he was dead. After I seen him, I went up to Foley. He was above, and I rapped three quarters of an hour for him and told him about it. I tried to get him to go down along with me, he wouldn’t come near, and he shook like a leaf on a tree.

“Have you seen him since?”

“No, because I’ve not been up there at night since, but others there have seen him. Mostly they see him as a bright light. Last night they saw a light leaving the dock where he fell in—a light that was about twice the size of a streetlamp, and floated on the water, but wasn’t in a boat, nor wasn’t any light in the world. It was between twelve and one o’clock, just about the same time I seen him.

“You insist you weren’t scared?”

“No, I tell you! I wasn’t a bit more scared than I am now, but of course I was a little excited.”

“How did he look?”

“Just as he looked when he was alive. Only his face looked like a dead man’s face. His two hands were in pockets, his cap was drawn over his eyes, and he had his old coat on just as he used to go about. I’m sure it was no joke. If it was, I’d soon find it out. The boys up there know me too well to try playing any jokes on me. I ain’t one that takes jokes from anybody.”

Along the way, Blavatsky explained to Captain Murphy that the spirits of those who possessed great intellect in life could, on occasion, return to communicate with the living.

“But this man was not a genius,” said Captain Murphy. “He was a decrepit old man, and something of a bummer.”

“That is just the reason,” Blavatsky said, “why his spirit returns in this shape. If he had been possessed of a great mind, he would not have returned in bodily shape. He would have come mentally.”

They party arrived at the skeleton of an old pier just before midnight. A large crowd of on-lookers had already assembled. (Absent, of course, were the other neighborhood watchmen—who could not be persuaded to go near the spot.) The party made their way down from the street to the river on a narrow foot path which cut through two rows of massive lumber piles. On the left, protruding from the wharf, was the skeleton of an old pier. The planking had long-since rotted away. The timber frame was all that remained. It was under this pier where the body of “Old Shep” was found. It was face down in the water near a large rock, the back of his head bobbing with the tide. It was also under this pier where the spectral light emerged.

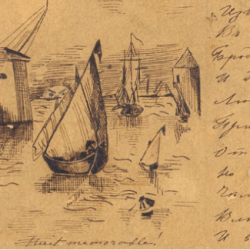

East River Ferry Boat.[10] (Library of Congress.)

“There goes The Maryland now,” said Capt. Murphy. “Night before last night, as she was passing here, her pilot saw the light right in front of him and whistled for it to get out of the way. It kept ahead of him some distance, and then disappeared. The gate-keeper of the 34th Street Ferry saw it plainly on the same night, and the ferry-pilots are going to try to run it down when they see it again.”

It was a rather bleak starlit night, and the Theosophists sat for hours , well-wrapped, on a pile of lumber by the river side. They beguiled the time with smoking and chaff with the crew of reporters, jokingly pressed Blavatsky to contact the spirit.[11]

“You mustn’t laugh while you’re waiting for the ghost,” Blavatsky said. “Seriously, you never can see any spirits when you laugh. This is a good night for a phenomenon. The moon helps it—and it is dry. You never can see any sights on a wet night.”[12]

Old Shep’ did not manifest his “disreputable eidolon” that night and in due course the Theosophists made their way back home. As they neared their destination, they passed innumerable stables. The district, which was bounding with industry during the day, was completely dark at night, save for the dim lights of an occasional livery stable, a streetlamp, or corner saloon. At last they reached The Lamasery, where they vexed the remainder of night at the waste of a whole evening.[13]

~

It was still early in the evening the next day when they again took up the subject of Old Shep. The sound of the blacksmith’s hammer mingled with the tinkling bell of the horse-car.[14] The mystery of Old Shep was apparently solved. Evidently it was just some prank.[15] Silence fell on the small gathering who sat smoking in a room within The Lamasery. The mood was of contemplative stillness. The sphinx statue, sitting on the mantel, seemed to embody the spirit of the room perfectly. The group were lounging on divans scattered about the parlor. A huge crystal ball—suspended by an invisible cord in the center of the room—with strange pictures of deserts and pyramids somehow appearing in the center of the orb. The walls were drab, but the hallway was bright, and its illumination bled a sort of pale twilight into the room. Fragrant clouds of Arabian tobacco filled the air, mingling with aroma of tea and sweetmeats passed about the room.

The Grand Hotel.[16]

Blavatsky was entertaining an old friend, Lydia Pashkova, who arrived in New York on March 11, 1878, after “thirty days of hectic navigation” from Rio de Janeiro. [17] The stop was the latest in her tour around the world.[18] Settling into her rooms at the luxurious Grand Hotel at Broadway and Thirty-first Street, the Russian adventurer was inundated with spectacle and a torrent of visitors, turning the heads of half a dozen artists and hommes d’affaires since her arrival. She met Alfred Harrisse, of the Haitian diplomatic service, who introduced her to the Bohemian artists known as the “Tilers.”[19] She was surprised to find Blavatsky among the many new faces who called on her, for she had last seen her during her travels in the Levant.[20] She spent many years in the East and was once a guest of the Egyptian Khedive (whose mother presented the Countess with an immense pearl that she now wore as a great-pin.) Her radiant black eyes gleamed like her jewelry as she half-reclined on the divan, pretending to smoke a cigarette. Others in the party were Alfred Harrisse, two reporters, including David Curtis, a Turk gentleman (who preferred his own coffee over tea, and his nargileh over the Arabian tobacco,) and, of course, Olcott and Judge.

Lydia Pashkova.[21]

“A ghost, yes. Why not?” Blavatsky said. “I have seen many ghosts. It is not a question of whether there are ghosts, but of whether they are seen. Doubtless the ghost of Old Shep was there. The only doubt is whether the officer really saw him as he says he did.” She took a drag, “I believe he did.”

The Turk opened his mouth to speak, but remained silent.

“What, then, is a ghost?” Harrisse asked.

The Turk slowly nodded in agreement with the question before pressing his lips on the amber mouthpiece of his water-pipe.

“There are ghosts and ghosts,” Blavatsky said. “The air that we breathe is permeated by a subtler fluid that corresponds to it as the soul corresponds to the body of man. It is the astral fluid and in it are the thoughts of all men, the possibilities of all acts, as on the photographer’s plate are images that remain unseen until revealed by chemical action. So the last dying thought of any person, if it be intense enough, becomes objective, and under favorable conditions is very apt to be seen. Only a little while ago the newspapers of this city reported the case of a man who committed suicide in his bathroom. A friend ran for a doctor, against the remonstrance of the dying man. On the way he was startled at seeing for a moment the image of the dying man, clad only in his night-shirt, grasping his pistol and bleeding from his death wound. It was at a considerable distance from the house. The apparition disappeared almost instantly. It was the intense desire to stop his friend that became objective, as the astral man left the physical. So it is with many other apparitions. In haunted houses the last thought of the victim of a crime may remain, and the tragedy be reenacted perhaps thousands of times before it fades away. It is likely that in the case of Old Shep, the watchman, he does not know that he is dead, and his last thought was probably that he was going on his rounds until that thought fades away, and under certain conditions he will be visible to the physical eyes of those around him.”

“Pardon me,” a reporter said, “did you say that perhaps he did not know he was dead?”

“It is recorded,” Olcott gravely said, “that many persons do not know when they are dead, and that they go around afterwards in great perplexity, because no one pays attention to them. They feel as well as ever, and talk to their friends, and are almost frantic at not being able to get replies.”

There was more silence. The tobacco smoke seemed to take the shape of the very phantoms discussed in the increasingly macabre conversation.

“I have many times hunted ghosts,” the reporter said, “but I was never lucky enough to shoot one. They are very shy birds.”

“In America, yes,” said Blavatsky. “In the Northern countries, and in the East, it is different. The conditions are different.” Blavatsky turned to Pashkova, “Chto vy dumayete?” and continued to speak very rapidly in Russian.

While the two Russian women talked, Olcott waxed philosophical. “The theory of crime being propagated by invisible seeds as disease,” he said, caused “epidemics of crime…devastating countries…” The theory that criminality was a treatable infectious disease, had gained traction with the writings of medical authorities such as, Dr. Benjamin Rush—a signer of the Declaration of Independence. “Many writers have spoken of it,” Olcott said, listing many writers, “but it has its foundation in fact. The astral crimes remain and influence all those who come in contact with them. Thus, it happens that the air and the very ground become saturated with sin in some communities. I have been told that.”[22]

“I remember,” said Blavatsky, suddenly in English “a governess I had when I was a child. She had a passion for keeping fruit until it rotted away, and she had her bureau full of it. She was an elderly woman, and she fell sick. While she lay abed, my aunt, in whose house I was, had the bureau cleaned out and the rotten fruit thrown away. Suddenly, the sick woman, when at the point of death, asked for one of her nice ripe apples. They knew she meant a rotten one, and they were at their wits’ end to know what to do, for there were none in the house. My aunt went herself to the servant’s room to send for a rotten apple, and while she was there, they came running to say that the old woman was dead. My aunt ran upstairs, and I and some of the servants followed her. As we passed the door of the room where the bureau was my aunt shrieked with horror. We looked in, and there was the old woman eating an apple. She disappeared at once, and we rushed into the bedroom. There she lay dead on the bed, and the nurse was with her (having never left her one minute for the last hour). It was her last thought made objective.”

Pashkova made an attempt to converse. Though understanding some English, she spoke it very poorly. Discarding her cigarette, Pashkova’s black eyes glistened as her graceful gesticulations accentuated musical cadence of her voice.

“Yest’ mnogo dukhov na severe. Na Vostoke mnogo magii…”

Olcott, who had an impressive knack for language, did his best to keep a running translation of the Countess’ story.

“In the North there are many apparitions,” he said in slow, deliberate, tones, “In the East there is much magic.”

“Ya videl kak dukhi, tak i magiyu mnozhestvo raz…”

“I have seen both apparitions and magic scores of times…”

Olcott continued in deliberate tones, frequently dropping into the vernacular, and making no gestures—except stroking his bushy beard. “In St. Petersburg there is standing at the present time a house that was built by one of the male friends of the Empress Catherine. I hired this house, and the day after people began to tell me I was foolish. They said it was haunted. But I went to live there. I was brave enough till I was really in the house, and then I got frightened. The principal salon of the house was an immense room with marble pillars. On the wall was a picture of the soldier who built the house. He was all rigged out with crosses and diamonds and ribbons and such on his breast. They said he walked around at night. So we all sat up waiting for him the first night, and at 12 o’clock we looked for him. All was still. Our hearts jumped up and down. Suddenly the close struck 12. We looked at the picture, and then we looked out into the hall. We saw nothing.

“Another night and another we looked. We saw nothing. We were all afraid. I had a maid to sleep in my room. Many nights we slept thus. At length one night, just after 12, a lackey came running upstairs. He was pale. ‘Come, come,’ he whispered, ‘the ghost walks.’ We threw on something or other (I can’t make out the name of it), and all went downstairs to the grand hall. The soldier was walking up and down. We watched him. He had all his diamonds and things on his coat. They sparkled in the faint light of the hall lamp. He walked to the door of the salon, which was closed. He walked through without opening it. We opened it and followed. He was walking up and down the room. We looked for the picture. It was not there. Where it had been the wall was black. He went to the middle of the room. Suddenly, he stopped. He shuddered. He was no longer there. We looked at the wall. The picture was in its place. Voila!”

“It is nothing,” Blavatsky said. “There are many such houses in Russia. In Pavlovsk, stood a house that no one would enter, for the windows were all broken out and there were noises there at night. It was in the time of the Emperor Nicholas I. He said he would stop the foolish stories, and he had new windows put in and surrounded the house with troops. At midnight a crash was heard and the windows were broken out from the inside. The Emperor entered. There was no one there. Many nights he did this, and it was the same. This is historical.”[23]

Once again, Olcott translated the Countess’ words as she resumed speaking, “I have seen the procession that goes every year to the shrine between Cairo and Alexandria. The dervishes go on camels and horses and ride over the people that throw themselves down to make a road for them. Little children and men and women lie, and the beasts walk over them, and no one is hurt. Then there are the dancing dervishes that spin around, till they go up in the air, and it takes three or four men to pull them down. And some of them stick knives through their legs and through their throats. The points of the knives come out on the other side. Blood runs down. They pull out the knives. They pass their hands over the wound. It is healed. There is not even a scar. Hoopla!…I mean…Voila!”

“Superstition,” said a reporter under his breath.

The Turk opened his mouth to speak, but again remained silent.

“It is no more superstitious,” said Olcott (the Countess recognizing the word began talking again) “than the practices of our Christians. I have seen an image of the Virgin that was worshipped. It is the custom to take it on certain days, in a procession from house to house. The women and children who want to be learned take school-books in their aprons and allow the image to be carried over them, and they think that as it passes all the knowledge in the books passes into their heads.”

The Turk closed his mouth.

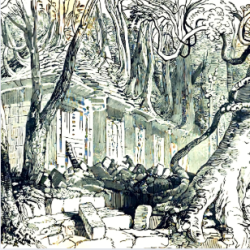

“I was once traveling between Baalbek and the river Orontes,” continued the two speakers, “and in the desert I saw a caravan. It was Mme. Blavatsky’s. We camped together. There was a great monument standing there near the village of Dair Mar Maroon. It was between Lebanon and the Anti-Lebanon. On the monument were inscriptions that no one could ever read. Mme. Blavatsky could do strange things with the ‘spirits,’ as I knew, and I asked her to find out what the monument was. We waited until night. She drew a circle and we went in it. We built a fire and put much incense on it. Then she said many spells. Then we put on more incense. Then she pointed with her wand at the monument and we saw a great ball of white flame on it. There was a sycamore tree nearby. We saw many little white flames on it. The jackals came and howled in the darkness a little way off. We put on more incense. Then Mme. Blavatsky commanded the spirit of the person to whom the monument was reared to appear. Soon a cloud of vapor arose and obscured the little moonlight there was. We put on more incense. The cloud took the indistinct shape of an old man with a beard, and a voice came as it seemed from a great distance through the image. He said that the monument was once the altar of a temple that had long since disappeared. It was reared to a god that had long since gone to another world.[24]

Camp in Lebanon.[25]

“‘Who are you?’ said Blavatsky?

“‘I am Hiero, one of the priests of the temple,’ said the voice. Then Mme. Blavatsky commanded him to show us the place as it was when the temple stood. He bowed, and for one instant we had a glimpse of the temple and of a vast city filling the plain as far as the eye could reach. Then it was gone, and the image faded away. Then we built up big fires to keep off the jackals and went to sleep.”

“Yes, and she was finely scared, I can tell you,” Blavatsky said, laughing.

Pashkova told a many more tales about the adventures she had with Blavatsky; how her host summoned spirits at will, performed magical feats just for fun, and fended the night with a story about the two of them entering the great pyramid at night and performing incantations in the chamber of the Queen’s chamber.[26]

[1] Five years earlier (1871) there was a squatter settlement on the rocks at the corner of Forty-first Street and Tenth Avenue. The squatters were evicted from their shanties and the larger part of them migrated to a row of brick buildings that were recently erected, on what was the former site of large swill milk stables on Thirty-ninth Street between Tenth and Eleven Avenues. The place soon got the name Battle Row. Across the way in the same block was a cluster of rock shanties known as Hell’s Kitchen. [“End of an Old Feud.” The Buffalo News. (Buffalo, New York) December 22, 1881; Willard, Frances E. “A Visit To Madame Blavatsky.” The Chautauquan. Vol. XI, No. 4. (July 1890): 466-468.]

[2] City History Club of New York. Historical Guide to the City of New York. Frederick A. Stokes. New York, New York. (1909):Top of FormBottom of Form 121; Rosenbaum, S. “When The Gay White Way Was Dark.” Valentine’s Manual of Old New York. No. 7 (1923): 114-137.

[3] “The Eighth Avenue Lamasery” was the name by which the Head-quarters of our Society were generally known in New York, ever since the name was given to it by the writer – one of the wittiest and cleverest reporters of New York.” see D.A.C. “Ghost Stories Galore.” The Theosophist. Vol. V, No. 7 (April 1884): 167-168; “Curtis, David A. “Theosophists To Meet.” The Morning News. (Savannah, Georgia) April 22, 1888.

[4] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume I. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1895): 333.

[5] AI enhanced images from: Costello, A.E. Our Police Protectors: History Of The New York Police From The Earliest Period To The Present Time. A.E. Costello. New York, New York. (1885): 332, 337.

[6] Costello, A.E. Our Police Protectors: History Of The New York Police From The Earliest Period To The Present Time. A.E. Costello. New York, New York. (1885): 332; McGrath, Thomas Francis. History Of The Ancient Order Of Hibernians From The Earliest Period To The Joint National Convention At Trenton, New Jersey, June 27, 1898. T.F. McGrath. Cleveland, Ohio. (1898): 27.

[7] “Waving The Green.” New York Herald. (New York, New York) March 19, 1878.

[8] https://collections.mcny.org/asset-management/2F3XC5CLXMB0?FR_=1&W=1201&H=610.

[9] Costello, A.E. Our Police Protectors: History Of The New York Police From The Earliest Period To The Present Time. A.E. Costello. New York, New York. (1885): 338-339.

[10] Johnston, John, photographer. The Fulton ferry boat, Brooklyn, N.Y. New York, 1890. July. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/97505116/.

[11] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume I. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1895): 333.

[12] “Personal Notes.” The Brooklyn Times-Union (Brooklyn, New York) March 21, 1878; “Ghostly East-Side Sights.” The Sun (New York, New York) March 21, 1878; “Old Sheppard’s Restless Spirit.” New York Times. (New York, New York) March 21, 1878.

[13] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume I. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1895): 333; Rosenbaum, S. “When The Gay White Way Was Dark.” Valentine’s Manual of Old New York. No. 7 (1923): 114-137.

[14] Rosenbaum, S. “When The Gay White Way Was Dark.” Valentine’s Manual of Old New York. No. 7 (1923): 114-137.

[15] “The East River ghost has been caught, and it is now lying on its back in the cabin of the Police-boat Seneca. From the character of the spirit, it is certain that it never assumed the shape of the old Watchman Sheppard or frightened a brave Policeman on a dark night. It is a piece of inch board, about 30 inches long by 8 inches wide, well water-soaked, with a tin lamp from a ship’s lantern securely nailed in the middle. On the bow end is a little wooden figure, somewhat resembling a child’s jumping-jack. Several days ago, as a boat’s crew from the Seneca were pulling ashore, this machine was seen floating in the water, and one of the men picked it up near the foot of East Thirty-ninth-street. Nothing was thought of it at the time; but when, in yesterday’s Times, the story was told of the fright over mysterious lights floating in the river, an officer from the Seneca went to Police Head-quarters and explained the puzzle. It is supposed that some of the mischievous boys that infest the neighborhood invented the ghost to frighten the superstitious night-watchmen and operated it with a string from convenient board-pile” [“The East River Ghost Caught.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) March 22, 1878.]

[16] AI enhanced image from: Edwards, Richard. New York’s Great Industries. Historical Publishing Company. New York, New York. (1884): 150.

[17] Pashkova led a thrilling life of romance. She was the only child of a Russian bahrin (landlord, or “serf-proprietor,”) the “owner of 7,000 souls,” who was the descendant of ancient Tartar princes. In her youth she “became morbidly fevered,” and experienced transcendental visions which inspired her to compose hymns and epic poems. Her father intervened, endeavoring to raise her “according to masculine principles.” This meant teaching her how to wrestle, fence, and use a revolver. But, having also studied in elite private schools, Pashkova was likewise instilled with the ideals that Catherine the Great imported from France in generations past. Her father did his best to “emancipate the intellect of his heiress,” but to no avail. At the age of sixteen, Pashkova won acclaim among the Muscovite literati with her debut novel, The Princess Vaira Gleniski. That same year she fell “desperately in love” with her nurse’s son, Ivan the Moujik. Her father, an owner of serfs, was mortified by the thought of a peasant for a son-in-law.[17] Pashkova, being as strong-willed as her father was resolute, insisted on becoming Ivan’s wife (even threatening to starve herself if she were not allowed to take him.) Ivan was soon discovered hanged outside the house. Pashkova was sent to Moscow that same evening and presented with a suitor whom she was told she must accept. Marriage freed her from the tyranny of her father, but within a year she was divorced, and living in her father’s Moscow mansion. She created one of the most fashionable salons of the city, and at the very zenith of her popularity, she found a new husband closer to her ideal, the millionaire, Ippolit Pashkov. The newlyweds spent the subsequent year at Pashkov’s mining estate in the Urals, before relocating to Egypt when her husband was chosen to represent Russian interests in the Khedival court. The couple spent many years in the East and was once a guest of the Egyptian Khedive (whose mother presented the Countess with an immense pearl that she now wore as a great-pin.) It was during this time when she first met Blavatsky. Tired of leading the Russian colony in Egypt, Pashkova separated from her husband, and set out on a journey through Syria, Palestine. Continuing her journey, Pashkova went to the Mediterranean, and went on a yachting cruise in the Levant, visiting Italy and darting off to Mount Lebanon. It was during this time, while traveling in the caravan of Omer Pasha in April 1872, that she met Blavatsky for a second time.[17] Pashkova, by this point, having written a number of successful novels, became a corresponding member of the French Geographic Society. It was through this connection that she commenced her journey around the world. Tired of leading the Russian colony in Egypt, Pashkova separated from her husband, and set out on a journey through Syria, Palestine. Continuing her journey, Pashkova went to the Mediterranean, and went on a yachting cruise in the Levant, visiting Italy and darting off to Mount Lebanon. It was during this time, while traveling in the caravan of Omer Pasha in April 1872, that she met Blavatsky for a second time. Pashkova, by this point, having written a number of successful novels, became a corresponding member of the French Geographic Society. It was through this connection that she commenced her journey around the world. [“Suicide of a Lady Novelist.” The Irvine Herald, and Cunninghame Advertiser. (Irvine, Scotland) May 31, 1879; Rawson, A.L. “Two Madame Blavatskys—The Acquaintance Of Madame H.P. Blavatsky With Eastern Countries.” The Spiritualist. Vol. XII, No. 14 (April 5, 1878): 165-166; Entsiklopedicheskiy Slovar’ Vol. XXII. I.A. Effron. Saint Petersburg, Russia. (1898): 63-64; “Obituary.” Historical Bulletin. Vol XXXVIII (November 1889): 460; “Blavatsky, H. Letter 7: H.P.B. to The Director Of The Third Department [26 December 1872]. In J. Algeo (Ed.), The Letters of H. P. Blavatsky: Volume 1, 1861-1879, Volume 1; Volumes 1861-1879. Quest Books. Wheaton, Illinois. (2003): 24-29.]

[18] Arrived March 11, 1878, from Rio de Janeiro on the Donati] “New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1891,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVSK-ZWN5 : 20 February 2021), Lydie Paschkoff, 1878; citing Immigration, New York City, New York, United States, NARA microfilm publication M237 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), FHL microfilm 295,775.

[19] David A. Curtis writes: “[Pashkova] met Mr. Harrisse, of the Haytian diplomatic service, and was by him introduced in a small social circle of friends, among whom was an old friend, Mme. Blavatsky.” [Curtis, David A. “A Modern Sibyl.” The Los Angeles Evening Express. (Los Angeles, California) April 21, 1888. ] A “Mr. A. Harrisse, Attaché Haytian Consulate, New York,” is listed as a member of the Diplomatic Corp. in 1878-1879 at that time. The name Alfred Harrisse is also the name provided for Secretary of the Haytian Pavilion in the 1893 World’s Fair. [Official Congressional Directory. U.S. Government Printing Office. Washington, D.C. (1879): 125; Handy, Moses Purnell. World’s Columbian Exposition 1893 Official Catalogue: Part I. W. B. Conkey Company. Chicago, Illinois. (1893): 20.]

[20] In a letter to Le Figaro (Paris,) dated March 14, Pashkova describes her impressions of America, which resembled Blavatsky’s “The Voice” article for the Tiflis Bulletin (e.g. allusions to Victoria Woodhull and Demosthenes, Adelina Patti, and the exaggerated widespread use of personal phonographs) that it appears that Blavatsky gave her all of this “news,” or even wrote the letter herself. Pashkova’s letter stated: “Just now I had a visit from one of my old friends, a philosopher, author of a book which is all the rage in London […] This lady is affiliated with every possible society—and there are strange ones in this country—So, to begin with, she is part of the Society of Buddhists. A rajah of India offers twenty-five million francs if we manage to build a Buddhist temple in New York, to demonstrate that Jesus Christ is only a derivative of Buddha. The purpose of this Society is the overthrow of Christianity and the building up of the brotherhood of peoples, and, moreover, the ousting of the English of India.” [Paschkoff, Lydie. “Figaro Pic-Nic.” Le Figaro. (Paris, France) April 4, 1878.]

[21] AI enhanced image from: Paschkoff, Lydie. “Voyage À Palmyre.” Le Tour du Monde. Vol. XXXIII. (1877): 161-176.

[22] Banner, Stuart. The Death Penalty: An American History. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. (2009): 103.

[23] “Ghost Stories Galore.” The World. (New York, New York) April 21, 1878; D.A.C. “Ghost Stories Galore.” The Theosophist. Vol. V, No. 7 (April 1884): 167-168; Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume I. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1895): 333-335.

[24] “On ne pouvait se persuader qu’il existât une ville si grande dans un endroit si écarté. Depuis, les voyageurs Dawkins et Wood levèrent tous les doutes. Nous avions apporté de Damas des feux d’artifice, nous les fîmes allumer le soir. Les ruines furent animées par les cris de joie de nos hommes qui couraient à droite et à gauche en portant des feux Bengale. Cette illumination produisit un effet féerique.” (One could not believe that such a big city existed in such a remote place. The travelers, Dawkins and Wood, have since removed all doubts. We brought fireworks from Damascus, and lit them in the evening. The ruins were alive with the joyous cheers of our men, who ran about carrying Bengal lights. The illumination produced an enchanting effect.) see Paschkoff, Lydie.“Voyage À Palmyre.” Le Tour du Monde. Vol. XXXIII (1877): 161-176.

[25] AI enhanced image from: Paschkoff, Lydie. “Voyage À Palmyre.” Le Tour du Monde. Vol. XXXIII. (1877): 161-176.

[26] “Ghost Stories Galore” The World (New York, New York) April 21, 1878; Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume I. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1895): 333-335.