THE DOUKHOBORS

In May 1818, during Andrei Mikhailovich’s last stay in St. Petersburg, Alexander Pavlovich visited Novorossiysk. While touring Odessa, the Tsar was convinced of the unforgettable merits and benefits of the region. Following the departure of Duke Richelieu from Russia, Count Louis de Langeron was appointed Governor General of the Novorossiysk Territory. He was the personification of the chevalier loyalist from the times of Henry IV; a brave general, a kind, honest person, but a dissatisfied joker, and an uninterested administrator. His absent-mindedness resulted in a humorous incident during Alexander Pavlovich’s visit. When Count Langeron left his office one day, he locked the door and left, forgetting that the Tsar was still inside the room. Although the reign of Count Langeron was short, it was not without benefit to the region, as he continued the policies laid out by Duke Richelieu.

The Tsar’s tour took him through Crimea, through the Molokan Colony. Kontenius, who was now retired, visited the Tsar to thank him for the pension he received. The Tsar was extremely pleased with the colonies, and attributing their success to the efforts of Kontenius, embraced the retiree and asked him to return to service and assist General Inzov. When leaving the colonies, the Tsar personally pinned the ribbon and star of the Order of St. Anne (1st Class) on Kontenius. This astonished a great many people, as Kontenius only held the rank of State Advisor, and this award entitled him hereditary nobility.

Andrei Mikhailovich returned to Ekaterinoslav where, on January 31, 1819, Elena Pavlovna gave birth to their second child. another daughter they named Ekaterina “Katya.” By this time Alexander Pavlovich had returned to St. Petersburg. The Tsar was pleased to discover that Grellet and Allen, two of the Quakers whom he met in England, had decided to take him up on his offer, and were making a tour of Russia. The Quakers arrived at the private apartments of Alexander Pavlovich on the evening of February 10, 1819, where they found him sitting alone. Imploring them to sit by his side on the sofa, Alexander Pavlovich received them with great affability, “like old friends,” he said. They reminisced over their time spent in England, the Tsar stating, “his mind was encouraged and strengthened under the trying circumstances then attending him.” He then made many inquiries of a religious character. He asked about the nature of their various religious engagements since arriving in Russia, and in what state they had found the public establishments, particularly the prisons.

The Quakers were glad to have the opportunity to acquaint the Tsar with the wretched situation of several of them, as well as the dismal particularities of the poor houses. They especially alluded to the prison at Abo.

“These things ought not to be,” said the Tsar, much affected. “They shall not continue so.”

Alexander Pavlovich was very interested in the subject of public education, and the Quaker, therefore, told him of the visit they had made to the Lancastrian School, and how greatly pained they had been in noticing there (and at the printing office) that the lessons were a selection of sentiments calculated to demoralize the people and bring them into a far worse state.

“We had been induced to begin to prepare a selection from the Scriptures, under the name of ‘Scripture Lessons,’” said the Quakers. They then gave the Tsar a brief outline of the contents of the little work.

The Tsar remained absorbed deep in thought for a few moments and then said: “You have done the very thing that I was anxious should be done. I had for a long time been contemplating how that mighty engine, general public education, might be used for the promotion of the Kingdom of Christ, by bringing the people to the knowledge of the dear Redeemer, and to the practice of Christian virtues; send me immediately what you have prepared.” After this, the Tsar said: “Before we separate for the present, let us spend a short time in religious retirement together.” They were disposed to do so and bowed their heads together in prayer.

In a subsequent meeting, the Tsar told the Quakers of the changes he had made in the prisons per their advice and asked that in the course of their visit through Russia, they would communicate directly to him, whatever they might notice in the prisons.

“I have carefully looked over the Scripture lessons that you have prepared, and I am delighted with them,” said Alexander Pavlovich. “Had you come to Russia for no other service than this, it would be accomplishing an important work.”[1]

By May 1819, Grellet and Allen were in Ekaterinoslav, where Kontenius and Andrei Mikhailovich escorted them through the religious communities (Kontenius serving as translator.) At the Mennonite colonies near Altona, they lodged with a young man, one of their ministers, who, with his wife, gave them a kind reception.[2] Their experience with the Doukhobors was another matter, but that requires a revisit of Doukhobor beliefs.

Some Elders (leaders) of the Doukhobors said that the founder of their doctrine was a retired non-commissioned officer who was a prisoner of the Prussians during the Seven Years’ War, and during this war lived for quite a long time with the Moravians. It was alleged that this soldier composed the Doukhobor doctrine from the dogma of Moravians after his return to Russia. Some said he was a former Prussian military officer who expatriated to Kharkov and preached ideas similar to the Quakers.[3] Others claimed that the Balkan Bogomils inspired the movement. There were not a few who claimed their teachings were derived from the three Jewish youths (Hanniah, Mishael, and Azariah) whom Nebuchadnezzar threw into the fiery furnace. Then again, according to a Doukhobors confession of faith given in 1791 to Kakhovsky (Governor of Ekaterinoslav,) the sect began in the village of Nikolskoe, in the Pavlograd District of the Ekaterinoslav Province. Whatever their true origins were, by the end of the 18th century, the Dukhobors were scattered all over Russia, but their primary centers were in the provinces of Kharkov, Ekaterinoslav, and Tambov.

The Doukhobor religion was universalist and undogmatic, rejecting priesthood, as well as outward forms and rites. They believed that the “seed of God dwells within every man, as it dwelt supremely in the spirit of the man Jesus.” As such, the Dukhobors maintained that true believers could be found outside the Christian fold. The Dukhobors were capable of quoting the Bible to outsiders, they increasingly came to regard it as a book that deadened rather than enlightened the spirit and secondary to the living oral tradition of their psalms. They rejected the taking of oaths, and most Dukhobors refused military service, as it was inconsistent with a religion of love and pacifism.[4] The Russian government came to treat this community with great severity because it saw in Doukhobor teachings the seeds of potential social revolution. The Doukhobors among the Don Cossacks were exiled to Siberia in 1779, while the Kharkov Doukhobors were ordered to resettle in the Melitpol District near Molochnye Vody in 1793. Known for his religious tolerance, Alexander Pavlovich expressed a special fondness for the group. Despite the objections of Archbishop Iov, the Tsar offered the Dukhobor’s generous land grants and other funds. In 1804 the Doukhobors of Tambov and Voronezh were allowed to join their coreligionists under similar arrangements. They thrived in Molochnye Vody. The mildness of the climate, along with the fertility of the soil, contributed to the favorable growth of the sect.

Their autocratic leader at the time, Savelio Kapustin, introduced communal goods and collective labor to the Dukhobors. Though this was largely for his own benefit, under his strict supervision (and the community’s hard work,) the Doukhobors achieved a significant degree of prosperity.[5] Kapustin strictly punished drunkenness, fraud, and supervised the arrangement and order of houses. Many of the schismatics of other sects, deserters, (and even some of the Orthodox,) began to join the Doukhobors, which noticeably increased their population. Under the despotic rule of Kapustin, unsavory actions percolated in the community. It was said the Doukhobors tortured and put to death some of their apostates by burying them alive. There were signs that a similar cruel execution had befallen many unfortunate victims of fanaticism during Kapustin’s years. There were even allegations of a sexual nature. Kapustin was very cunningly, however, and hid these abuses from authorities under the veneer of feigned humility and meekness.

The Quaker visitors were initially very friendly with the Dukhobors when they first met, believing them to be kindred spirits, they were fond of calling them their brothers. Their opinion soured during their interviews. Grellet and Allen went to the abode of one of the Elders, a ninety years old man who was nearly blind, but very active in body and mind. He was the chief speaker of the fourteen Elders who were present. The Quakers had a long conference with the old Elder and found him to be very evasive in several of his answers to their inquiries. The Elders, however, did state, unequivocally, that they did not believe in the authority of the Scriptures.

“Do the Doukhobors believe in the Divinity of Jesus Christ?” asked Grellet and Allen.

“Christ was a good man,” said the old Elder (after a long hesitation.) “Every man who is able to acquire the strength to be a truly good man can do so through Christ and God.”

The Doukhobors explained that they looked upon Jesus Christ in no other light than that of a good man. They therefore had no confidence in him as a Savior from sin. They believed that there was a spirit in man, “to teach and lead him in the right way,” and in support of this, they were fluent in the quotation of Scripture texts.[6]

The faces of Grellet and Allen changed at this confession. Jumping up from their seats, with an expression of horror and indignation, the Quakers exclaimed in French: “Ténébre! Ténébre!” (“Darknesses! Darknesses!”) No! no! You are not our brothers!”[7]

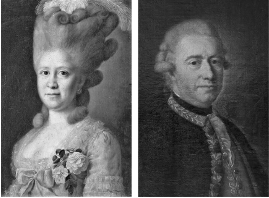

Elena Ivanovna & General Adolf Frantsevich Bandre du Plessis.

A curious incident involving Allen occurred in the Fadeev home before the Quakers left Ekaterinoslav. Hanging on their walls were two waist-length oil paintings of Elena Pavlovna’s grandparents. Elena Ivanovna was depicted in powder, with a rose on her chest. General Adolf Frantsevich, a handsome man with a noble, courageous, well-born face, was depicted in a Lieutenant General’s uniform, with powder on his head. Although the portrait did not contain any symbols, peculiarities, nor the slightest hint of the number three, there was nevertheless some mystery in this portrait—some peculiarity by which Freemasons could recognize him as belonging to their fraternity. Allen noticed the portraits hanging on the walls in the living room, and, pointing to General Adolf Frantsevich, he immediately announced: “This was a Freemason and the highest degree!”

“How did you know that?” asked Elena Pavlovna.

Allen excused himself by saying that he was unable to answer and, despite numerous requests, said nothing more.

In the Autumn of 1819 Andrei Mikhailovich and Elena Pavlovna went to the southern coast again. The painful condition resulting from rheumatism was getting worse for Elena Pavlovna, and the doctors recommended the rejuvenating health benefits of bathing in the sea. Here they met the new Governor of Tauride, Alexander Nikolaevich Baranov, a remarkably gifted official who would die far too young.[8] If relief followed, it was only to the weakest degree, and by the time they returned from Crimea, Andrei Mikhailovich had developed a strong fever.) Andrei Mikhailovich continued to wander around the colonies in 1819, surveying the empty steppes intended for the establishment of new German colonies (which never happened.)[9]

-

- NOVOROSSIYA

- The Arbiter Of Europe’s Destiny.

- The House Dolgorukuy

- Madame Krüdener

- Ekaterinoslav

- The Arabat Arrow

- The Mystery Of General Inzov

- The Doukhobors

- Pushkin

- Chuguev Military Settlement

- “The Blessed”

- The Decembrists

- Penza

- Independence

- Last Words Of Samuel Khristianovich Kontenius

- “Amid Coffins And Desolation”

- Rusalka

- Dead Souls

- Secret Passages

- Astrakhan

- Nevsky Prospekt

- Kalmyk Ulus

- Love And Ambition

- Duellistes

- Pyatigorsk

- A Heroine Of Our Time

- Winter Palace

- Zeneida R-Va

- Steppes

- Letter To Natalya

- Fire And Ice

SOURCES:

[1] Grellet, Stephen. A Concise Memoir Of The Remarkable Evangelist, Etienne De Grellet. Edward C. Alden. Oxford, England. (1877): 169-177.

[2] Sherman, James. Memoir Of William Allen. Henry Longstreth. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1851): 282-283.

[3] Hardwick, Susan W. “Religion And Migration: The Molokan Experience.” Yearbook Of The Association Of Pacific Coast Geographers. Vol. LV (1993): 127-141.

[4] Brock, Peter. “Vasya Pozdnyakov’s Dukhobor Narrative.” The Slavonic And East European Review. Vol. XLIII, No. 100 (December 1964): 152-176.

[5] Palmieri, Aurelio. “The Russian Doukhobors And Their Religious Teachings.” The Harvard Theological Review. Vol. VIII, No. 1 (January 1915): 62-81.

[6] Grellet, Stephen. Memoirs Of The Life And Gospel Labors Of Stephen Grellet: Volumes I & II. Henry Longstreth. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1860): 455-456.

[7] Fadeyev, Andrei Mikhailovich. Vospominaniia: 1790-1867. Vysochaishe Utverzhd. Yuzhno-Russkago. Odessa, Ukraine. [Russian Empire.] (1897): Part II: 45-49.

[8] Kravchuk A.S. “On The Biography Of The Tauride Civil Governor Alexander Nikolaevich Baranov (1793–1821) The Crimean Historical Review. No. 3. (2015): 59–73.

[9] Fadeyev, Andrei Mikhailovich. Vospominaniia: 1790-1867. Vysochaishe Utverzhd. Yuzhno-Russkago. Odessa, Ukraine. [Russian Empire.] (1897): Part I: 64-67, 70n-71n.