MADAME KRÜDENER

Klemens von Metternich, the Secretary of State of Austria, one of the architects responsible for restructuring of Europe, had come to fear Russia. With almost one million men in its standing army, Russia had nearly the same number of soldiers that Napoleon had under his command. Austria was a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic State (Italians, Germans, Magyars, Poles, Slovaks, Slovenes, etc.,) with conflicting loyalties, and with borders on all sides, Metternich feared the Austrian Empire could be easily overrun by enemy armies. He was suspicious of Alexander Pavlovich’s enigmatic character, and mystic motivations.[1] Then there was the Viscount Castlereagh, Britain’s Foreign Secretary, a man resolute in his determination to never see the rise of anyone like Napoleon ever again. Less concerned with Russia as Metternich, Castlereagh nevertheless desired a new balance of powers for the peace of Britain. Karl August von Hardenberg, Chief Minister of Prussia, was another element. He wanted to negotiate a European peace as quickly as possible, as he was anxious to restore stability in his country.

The Congress of Vienna opened on October 1, 1814, and would last for seven months. It was one of the most important assemblies of world powers to ever meet. The many purposes of the meetings included: 1. Redrawing Europe’s political map. 2. Protect the rule of the Great Powers (Austria, Prussia, Britain, and Russia) against the rise of revolutions like the French Revolution. 3. To keep Napoleon from regaining power. 4. Establish a fair balance of powers in Europe so lasting peace was ensured.

Courtly intrigue was not one of the Tsar’s strengths, and he was often outmaneuvered by career Statesman. The Congress was also preoccupied with the foolish endeavor of undoing the idea of the French Revolution (“liberty, equality, and fraternity,” etc.) Ideas of constitutional monarchies, representative governments, freedom of religion, and freedom of speech were never going away. The best that could be done was to enact policies to mitigate that which might enflame revolutionary impulses. It was soon realized that the Congress would be more beneficial to all if it was understood not as punishment for France, but rather the opportunity to establish a lasting peace in Europe. France, therefore, was included in the Great Powers, with a strong and equal voice.

Around an old woman named Baroness Juliane von Krüdener, or Madame Krüdener, appeared on the scene, appearing at the Tsar’s castle doors one evening during a recess in the Congress. Alexander Pavlovich, believing that God had sent him a messenger, allowed Krüdener into his chambers. A Livonian woman, and a widow of a Russian diplomat, Krüdener was a protégé of Jung-Stilling. After apologizing for her intrusion, she began scolding Alexander Pavlovich and demanded that he accept his destiny and the divine calling God had given him. That destiny being the creation of a Christ-centered peace in Europe. Impressed by her boldness, Alexander Pavlovich instantly accepted her as a spiritual guide. The Tsar, remembering his divine calling, returned to Vienna with renewed vigor and a determination to change his in the Congress. Alexander Pavlovich wanted the participants of the Congress to agree on one other point, a provision that would see the Great Powers form a “Holy Alliance” and a system of future congresses that would bring world leaders together to prevent further bloodshed. Positioning himself as a benevolent referee, he loosened his grip on Russia’s position regarding Poland in return for the realization of this scheme.

On March 7, 1815, the attendees of the Congress learned that Napoleon had escaped from Elba and was on his way back to France. The allies immediately pledged a coalition army. Most of the Russian army was still stationed in Poland, and it was unanimously agreed that Britain’s Duke of Wellington would be the supreme commander of the combined armies. This force would join with Russia’s Imperial Army and finally put an end to Napoleon. Three months later Napoleon lost at Waterloo.

After the Battle of Waterloo, Krüdener accompanied Alexander Pavlovich to Paris. On September 11, 1815, she stood beside the Tsar as they reviewed an immense military parade, after which 150,000 Russian troops assembled in seven gigantic squares. Then they kneeled in unison around seven large altars, a reference to John the Revelator’s seven churches, “the mystic number of the Apocalypse.” Alexander Pavlovich was convinced that he was witnessing the fulfillment of the prophecies from the Book of Revelation and that Russia’s Christian army “were equated with the new Israel.”[2] Krüdener’s pamphlet, Le Camp des Vertu, commemorating the Mass of Thanksgiving that the Tsar celebrated with the Imperial Army in the Plains of Vertus, was published in St. Petersburg soon after. The work framed the conflicts in Europe as a Holy War, and once again depicted the Tsar as a messianic figure in the theatre of the Apocalypse.[3] It said in part:

And from that distant land, which was only known as in a legend, came a simple people, who had not yet drunk of the cup of all iniquity; who had not yet deserted the God who had redeemed them. A long time previously they had been selected for the purpose of repeating once more that great lesson of all ages: that wise men know nothing, and that all things are revealed to babes. At their head was the man with a great destiny, designed before all ages, and created in order to be placed in opposition to him, who, thirsting for glory, was to be crushed by his own power. He was humble, this disciple of the greatest of masters; he was a child. At all times his advance was that of one who, by a mere breath, can overthrow worlds. The Almighty summoned Alexander, and he was obedient to His voice. The Almighty supported him; and, full of confidence in the future, with that infinite courage which, in the midst of national disasters made him reject a shameful peace, he was already the recipient of every promise; the fields of victory were already spread out before him, and already every heart that realized how all strength comes of God was opened to him.[4]

While still in Paris, Alexander Pavlovich presented his dispensation of the “Holy Alliance,” to his counterparts, God’s moral statement sent to bind all of the rulers of Europe in a “union of virtue, peace, forgiveness, and Christian brotherhood.” It was not technically a treaty, but rather an oath of future policy. Everyone but the Pope, the leaders of Britain, and the Ottoman Sultan signed it on September 26, 1815.

-

- NOVOROSSIYA

- The Arbiter Of Europe’s Destiny.

- The House Dolgorukuy

- Madame Krüdener

- Ekaterinoslav

- The Arabat Arrow

- The Mystery Of General Inzov

- The Doukhobors

- Pushkin

- Chuguev Military Settlement

- “The Blessed”

- The Decembrists

- Penza

- Independence

- Last Words Of Samuel Khristianovich Kontenius

- “Amid Coffins And Desolation”

- Rusalka

- Dead Souls

- Secret Passages

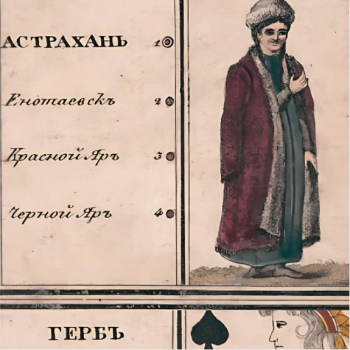

- Astrakhan

- Nevsky Prospekt

- Kalmyk Ulus

- Love And Ambition

- Duellistes

- Pyatigorsk

- A Heroine Of Our Time

- Winter Palace

- Zeneida R-Va

- Steppes

- Letter To Natalya

- Fire And Ice

SOURCES:

[1] Bennett, Richard E. 1820: Dawning Of The Restoration. Brigham Young University. Provo, Utah. (2020): 57‒80. [Chapter Three: “Tsar Alexander I: The King Of The North And His Holy Alliance.”]

[2] Zorin, Andrei. By Fable Alone: Literature And State Ideology In Late Eighteenth And Early Nineteenth-Century Russia. Academic Studies Press. Boston, Massachusetts. (2014): 288-324.

[3] Pesenson, Michael A. “Napoleon Bonaparte And Apocalyptic Discourse In Early Nineteenth-Century Russia.” The Russian Review. Vol. LXV, No. 3 (July 2006): 373-392.

[4] Ford, Clarence. The Life And Letters Of Madame De Krüdener. Adam And Charles Black. London, England. (1893): 214-218.