PUSHKIN

In early June 1820, on one of the hottest days of the year, Elena Pavlovna attended a dinner at the home of General Inzov. (Andrei Mikhailovich, being under the weather, was unable to attend.) Here she met the new Governor of Ekaterinoslav, Vikenty Leonovich Shemiot, a good man, but weak-willed and slow-witted. Although he was quite decent in all respects, he was very concerned about his own interests. His wife, Domitsela Martynovna Shemiot (née Princess Gedroits,) was an old friend of Elena Pavlovna’s mother. She too was there, along with her three young daughters, Elizaveta (19,) Eulalia (16,) and Evgenia (13.)[1] At this soirée, Elena Pavlovna met a young poet named Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin, whose new poem, “Ruslan And Lyudmila,” had made him famous practically overnight. His other works (those of a satirical and political nature,) however, had landed him in hot water.[2] Pushkin was sent to the southern frontiers for criticizing Tsar Alexander Pavlovich and the Russian Government in his works. Making his way down the banks of the Dnieper River, he found himself in Ekaterinoslav in late May 1820. Pushkin subsequently rented a little shack from a Jewish landlord named Krakonini in the suburb of Mandrykovka. The poet spent his free time bathing in the Dnieper (which ran behind his rooms) or watching the traffic on the river. At least one incident inspired a composition. From his rooms, he witnessed two convicts, shackled together, make their escape from the local prison. Though they were chased by guards, they managed to successfully swim to freedom on the other side of the river. This scene made its way into his unfinished poem, “The Robber Brothers.”

It could hardly be said that Pushkin was on his best behavior that evening. From the very first moment that Pushkin made his appearance, he threw the whole into extreme embarrassment, owing to the “eccentricity” of his attire. That is to say, he wore transparent muslin trousers without any underwear. Domitsela Martynovna, being very short-sighted, was the only guest who did not notice this “peculiarity.” Elena Pavlovna quietly advised her to take the girls out drawing room, discreetly explaining the necessity for their removal. Domitsela Martynovna, refusing to believe the possibility of such crude indecency, maintained that Pushkin was simply wearing “skin-colored summer trousers.” When she was finally assured of the bitter truth, she armed herself with her lorgnette and escorted her daughters from the room. While everyone was highly indignant and embarrassed, they tried to pretend that they did not notice anything, and Pushkin’s “prank” had no consequence.

General Inzov was then appointed Governor of Bessarabia and moved to the city of Kishinev. Andrei Mikhailovich paid him a visit on this occasion. Kishinev, bounded by the Dniester River, the Prut River, the Black Sea, and the Danube Delta, was the capital of Bessarabia. It was a colorful, animated town, that was colonized successively by the Greeks, Romans, Genoese, Moldavians, and the Ottoman Empire, before being ceded to Russia in 1812 with the Treaty of Bucharest. The majority of the inhabitants were Moldavians, large colonies of Bulgarians and Jews, a sizable population of Greeks, Turks, Ukrainians, Germans, Albanians, and a handful of French and Italians. The Russian presence there was mainly found in the military personnel and civil servants. The old town, with its narrow streets, bazaars, shops, and small houses with tiled roofs was spread out along the muddy banks of the Byk River. It was beautified with many public gardens with white acacias and Lombardy poplars. The new town, located on the hills above, was where the administrative offices were located. This is where the municipal garden, theatre, and casino, were located as well as the stone houses where the Governor, Military Commander, and Metropolitan lived.[3] Andrei Mikhailovich stayed in the house rented by General Inzov, a large stone building in an out-of-the-way place near the old town on a hill overlooking the Byk. Inzov and several government officials occupied the top floors, while Andrei Mikhailovich stayed in the two rooms on the bottom floor. Through the barred windows of the room, he could see the mountains beyond and the orchards and vineyards in the expanse.

Andrei Mikhailovich was not alone, as he was boarding with the Pushkin. The poet was sent to “repent for his pranks” under the guidance of the pious General Inzov. Not long after the evening at the dinner party (when Elena Pavlovna met him,) Pushkin came down with a fever and went to the mineral waters of the Caucasus with General Nikolay Nikolayevich Raevsky. It seems that he also became a Freemason while in Kishinev. Perhaps his interest in mysticism and the occult was only for research, but what is clear is that his story, “The Queen Of Spades, is filled with esoteric anagrams, Kabbalistic Gematria, and Masonic symbolism.[4] The most pressing mystery for Andrei Mikhailovich, however, was how to get some sleep. He had come on business and went to bed early. There were some nights that he did not sleep at all because these were nights that Pushkin (who shared the room,) did not sleep at all. He wrote, moved about noisily, declaimed, and recited his poetry in a loud voice. He would disrobe completely sometimes and perform “all his nocturnal evolutions in the full nakedness of his natural image.” The blue walls of their shared room were disfigured with the pearls of his untamed spirit, for Pushkin practiced his marksmanship by picking out letters with wax bullets from his pistol. Though he was sent to the southern frontiers as punishment, Pushkin continued to play pranks and compose scathing verses.

When returning to Bessarabia, Andrei Mikhailovich made a tour of Jewish Colonies in the Kherson Province. Despite legislative prohibitions, the Jews continued to trade in land, secretly own taverns, and “wander as vagabonds.” By law, they settled in separate communities from the ethnic Russians, yet Andrei Mikhailovich noted that they often quarreled strongly among themselves, and “there was no end to the complaints they made of one another.” He also noted in his report, that out of the several hundred families who resided here, there was scarcely a farmer among them, cultivation of land, rather, was outsourced to neighboring Russian villagers.[5]

The Russian Empire was a diverse, multicultural, multinational State. Of these peoples, the Jews were one of the most significant minority groups of the empire and accounted for nearly one-half of the Jewish population of the world (and for four percent of the population of the empire.) Imperial policies towards this community were hardly kind, and soon Anti-Jewish legislation resulted in the geographical manifestation of the Jewish Pale of Settlement. This settlement was an area in the western borderlands of the Russian Empire where the Jewish population was almost exclusively confined.[6] A series of committees created for the “improvement of the conditions of the Jews” began in 1802, just after the accession of Alexander Pavlovich to the throne.[7] In October 1804 the committee submitted to the Tsar its report on the legal position of Jews in the Russian Empire. This “Jewish Statute” was approved by Alexander Pavlovich in December 1804. This legislation was immediately felt by the rural Jewish populations, whose presence in villages was now illegal. They effectively returned to their legal position before the First Partition of Poland (1772,) when the Jewish presence in Russia was first legalized. Articles 34-41 of the Statute pertained to rural Jews. Jewish presence was prohibited in rural areas, and they were given the eviction date of January 1, 1808. This also meant Jewish leaseholders of taverns and inns on the highways and in the villages had to be terminated by this time. Another committee on Jews was formed in August 1806, and the committee members were divided on the practical enforcement of the legislation. Some feared that the mass eviction of rural Jews would elicit widespread support among Russian Jewry for Napoleon’s Grand Sanhedrin in Paris. Prince Viktor Pavlovich Kochubey suggested postponement in enforcing some measures of the Statute on practical grounds, citing the difficulties shtetls would face in assimilating evicted rural Jews.[8] Fears about the Sanhedrin were largely quelled after the Treaty of Tilsit and Alexander Pavlovich ordered the eviction of all rural Jews to begin by 1810. Despite this pronouncement, in practice, few rural Jews were evicted. Prince Kochubey proved to be correct in his belief that the shtetls could not properly absorb their displaced brethren. The rudimentary industry in the towns in the Pale of Settlement could not provide adequate economic conditions. The difficulties in the implementation of the Jewish Statute caused the eviction order to be suspended in December 1808.

In an attempt to encourage the Jews to adopt agriculture as a means of livelihood, about 381,000 acres of State land were allotted to them. (Only 3 percent of Russia’s Jews could properly be considered farmers at the time.)[9] This land, however, was not situated in Provinces adjoining the parts of the Empire where Jews could legally reside, but in the distant (and nearly unpopulated) Novorossiysk region. Though they were encouraged to resettle, they could not easily transfer themselves and their belongings. Nevertheless, the Jews who wanted to take up agricultural pursuits settled on these lands in 1806, and by 1810 some 600 Jewish families (3,640 people) were transferred to Kherson Province. This settlement scheme was terminated in 1810, however, as the Governor of Kherson reported that the mortality among the settlers was very great.[10]

-

- NOVOROSSIYA

- The Arbiter Of Europe’s Destiny.

- The House Dolgorukuy

- Madame Krüdener

- Ekaterinoslav

- The Arabat Arrow

- The Mystery Of General Inzov

- The Doukhobors

- Pushkin

- Chuguev Military Settlement

- “The Blessed”

- The Decembrists

- Penza

- Independence

- Last Words Of Samuel Khristianovich Kontenius

- “Amid Coffins And Desolation”

- Rusalka

- Dead Souls

- Secret Passages

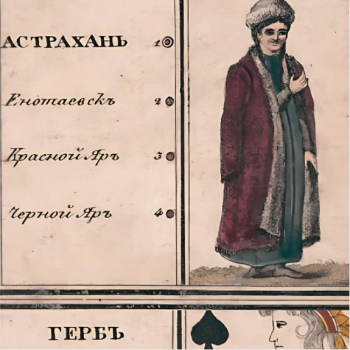

- Astrakhan

- Nevsky Prospekt

- Kalmyk Ulus

- Love And Ambition

- Duellistes

- Pyatigorsk

- A Heroine Of Our Time

- Winter Palace

- Zeneida R-Va

- Steppes

- Letter To Natalya

- Fire And Ice

SOURCES:

[1] Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. How I Was Little. A. F. Devrien. St. Petersburg, Russia. (1898): 247-252.

[2] Strakhovsky, Leonid I. “Pushkin And The Emperors Alexander I And Nicholas I.” Canadian Slavonic Papers / Revue Canadienne des Slavistes. Vol. I (1956): 16-30.

[3] Binyon, T.J. Pushkin: A Biography. Knopf Doubleday. New York, New York. (2007): 104-106, 120-121.

[4] Leighton, Lauren G. “Gematria In ‘The Queen of Spades’: A Decembrist Puzzle.” The Slavic And East European Journal. Vol. XXI, No. 4 (1977): 455–469.

[5] Fadeyev, Andrei Mikhailovich. Vospominaniia: 1790-1867. Vysochaishe Utverzhd. Yuzhno-Russkago. Odessa, Ukraine. [Russian Empire.] (1897): Part I: 64-68, 78, 92

[6] Rowland, Richard H. “Geographical Patterns Of The Jewish Population In The Pale Of Settlement Of Late Nineteenth Century Russia.” Jewish Social Studies. Vol. XLVIII, No. 3/4 (Summer–Autumn 1986): 207-234.

[7] Kalik, Judith. Movable Inn: The Rural Jewish Population of Minsk Guberniya in 1793-1914. De Gruyter. Berlin, Germany. (2018): 35-50. [Chapter Two: The Legal Position of Rural Jews in the Russian Empire.]

[8] Shtetl is a Yiddish word for small towns with a predominantly Ashkenazi Jewish population.

[9] Tal, Alon. “Enduring Technological Optimism: Zionism’s Environmental Ethic And Its Influence On Israel’s Environmental History.” Environmental History. Vol. XIII, No. 2 (April 2008): 275-305.

[10] Demidov, Pavel Pavlovich. The Jewish Question In Russia. Darling And Son. London, England. (1884): 28-30.