This next series of articles, “Novorossiya,” is a continuation of “Tournament Of Shadows.” Following the Russian Civil Servant, Andrei Mikhailovich Fadeev, it is a look at the colonization process on the Russian Empire’s southern frontier after the Napoleonic Wars.

— S.

THE ARBITER OF EUROPE’S DESTINY

In June 1814, Alexander Pavlovich and his sister, Ekaterina Pavlovna, visited England, where he was adoring crowds who hailed him as “the Christian conqueror who saved Europe.” Russia’s rapid march and triumphal entry into Paris had positioned the Tsar as the sole “arbiter of Europe’s destiny.” Nevertheless, he promised not to use Russia’s entrenched military position to gain an unfair advantage. Rather, Alexander Pavlovich promised to negotiate with the other allied powers and forge a lasting European peace. This proposal would lead to the Congress of Vienna, a series of international diplomatic meetings (1814–1815) where a layout for a new European political and constitutional order after the downfall of Napoleon.[1]

Alexander Pavlovich felt a calling. A spiritual renaissance for Russia. The coterie of mystics who advised him agreed. Prince Golitsyn even served as president of the Russian Bible Society. It was a branch of the British and Foreign Bible Society, an ecumenical organization that emerged during the evangelical Second Great Awakening that swept through Britain, Europe, and North America. (It owed its success to its avoidance of doctrinal controversies, and focusing on translating and distributing cheap Bibles without commentary.)[2] This is partly why he and Ekaterina Pavlovna agreed to attend the Meeting of the Quakers at Westminster on the morning of June 19. Both the Tsar and his sister conducted themselves like persons with undissembled piety. They even had the predominance of not hastily leaving after the meeting concluded. With condescension and kindness, they remained to shake hands with and notice several of the Quakers who were near them.

Stephen Grellet, a French American Quaker, remarked to Alexander Pavlovich the satisfaction of his having a sister such as Ekaterina Pavlovna.

“It is, indeed. She is the gift of Heaven, for she is sensible of the influence of the Divine principle on her own heart; it is no use to speak to those who have not felt it.”

He discussed the issue of slavery with the abolitionist Quaker, William Allen. “The Africans are our brethren and are like ourselves,” said Alexander Pavlovich, unequivocally declaring his sense of the enormity of the wretched institution. The Tsar further expressed his part in getting slavery abolished.

Before getting into the carriage, Alexander Pavlovich told Allen that he wished for a private conference the following day. As requested, Allen, Grellet, and another man, J. Wilkinson, arrived at the appointed hour. As soon as they entered the room, Alexander Pavlovich came forward to shake hands with each of them. Allen then presented the Tsar with books concerning the beliefs of the Society of Friends (Robert Barclay’s Apology, The Book of Extracts, William Penn’s No Cross, No Crown & Summary and Maxims, etc.) After he accepted the books, he turned around and expressed himself with great kindness and in very full terms told the delegates of the satisfaction he felt at having been allowed to attend the Friend’s Meeting.

“Was that meeting held in the same manner as those of your usual Meetings?” asked the Tsar.

“Yes, but there is not always speaking in our Meetings.”

“Do you then read the Scriptures in them?” asked Alexander Pavlovich.

“We are not in that practice; we believe true worship to consist in the prostration of the soul before God, and we do not consider it absolutely necessary for anything to be read or spoken to produce that effect.”

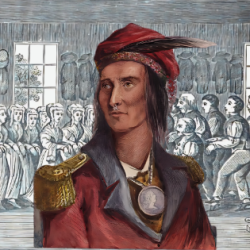

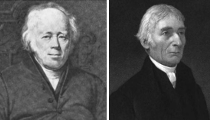

(Left) William Allen (Right) Stephen Grellet.[3]

“This is my opinion, also,” replied the Tsar, “and regarding prayer, have you any form of prayer?”

“We have not; because we believe that in prayer the soul must communicate its supplication in such a manner as best suits its condition at the time prayer is offered up.”

“I am one with you in sentiment respecting the spirituality of your worship,” said the Tsar. “I pray daily—not in any form, but as I am animated by the Divine principle in my own heart. I believe I can truly say there is not a day passes in which I do not pray, but it is not in any set form of words, for I soon found that my mind would not be satisfied without using such language as at the moment is applicable to its condition; but you know Jesus Christ gave a set form of words to his disciples?”

“He did; yet we conceive it was only to instruct them in which it was most essential they should petition for, without meaning to confine them to those very words on all occasions.”

“I think you are right,” said Alexander Pavlovich.

He then asked how the Quakers passed their time, and if they were consistent and happy in domestic life. Grellet responded by telling him how they divided the day.

“It is the most mature, and such as I should like,” the Tsar replied, “not as many who spend so much time in drinking wine, which is below the dignity of man.”

The Tsar then asked many questions in order to be made acquainted with the principle doctrine, discipline, and punctuality, of the tradition. The Quakers, or the Society of Friends, was founded by George Fox. Born in England in 1624, Fox began his ministry around 1650 and died in 1690. His most noted disciple and adherent was William Penn (the namesake of Pennsylvania.) Though it was an offshoot of Protestantism, it was persecuted by dissenters and State Church with equal impartiality. Even the Puritans, who came to America to find religious freedom, put Quaker necks in the noose of the gallows in Boston Common. Alexander Pavlovich, no doubt, was somewhat familiar with both places, as Adams had mentioned them. The ideals of Fox were simple in the extreme. He wished to return to the religion of primitive Christianity and to do away with the complications of creed and dogma. He wanted to abolish the luxury, ostentation, and un-Christlike lives of the people of his time. He taught that every person, regardless of race, creed, or condition, had within themself a spark of the divine spirit and that the whole of religion consisted in cultivating this Inner Light and manifesting it in daily life. If the divine interior guidance was faithfully sought and conscientiously followed, everything would fall into place. Fox taught that sin was a barrier to the manifestation of the Spirit of God, and that a humble, kindly, devout life was “the best soil for its growth and development.” As to all true mystics, God was a reality to Fox, not a faraway abstraction. Not only did he believe that a direct, personal, inner communion was possible, he believed it was frequently achieved. The effort to attain this inner guidance was the only true religious life.[4] Alexander Pavlovich seemed well-satisfied with the answers he received, especially regarding the operation of the Divine Spirit on the mind.

“Why don’t some of your people visit my country?” asked the Tsar affectionately. “If any of them go into my country on a religious account, don’t make applications to others but come immediately to me; I promise you protection and every assistance in my power. I shall be glad to see them.”

On hearing Grellet relate some particulars of his life, Alexander Pavlovich responded.

“I consider you as safely landed, whilst I have to combat troubles and difficulties, and am surrounded with temptations.”

Toward the conclusion of the audience, Grellet told of the strong desire he felt for the Tsar’s preservation and the heavy burdens and responsibilities that must necessarily fall on his shoulders.

After Grellet finished speaking, Alexander Pavlovich took him by the hand. “What you have said is a cordial to my mind,” he said with a countenance full of noble tenderness. “A cordial which will long continue to be a strengthening to me.” When he parted with the Quakers, he shook hands with each of them. “I have had great satisfaction in this interview and hope when parted we shall often think of each other,” said the Tsar. “I part with you as a friend and brother.”[5]

A few weeks later, on July 10, 1814, the Tsar met the mystic, Jung-Stilling, in Paris. They discussed the religious situation in Russia, the plight of Christians in the Ottoman Empire, and which confession best corresponded to the spirit of true Christianity.

“How does one practice true Christianity?” asked Alexander Pavlovich.

“Perfect abnegation, constant concentration, and heartfelt prayer,” Jung-Stilling replied.

“Yes,” answered the Tsar, “that’s exactly what I practice.”

“But how does Your Excellency manage to maintain this state amid so many activities?”

“I am sometimes able to reach it, but I must admit that it is becoming harder and harder.”[6]

Jung-Stilling then told the Tsar that a place of refuge would be needed to escape the turmoil of the looming eschaton and suggested a location somewhere in the Caucasus.[7]

-

- NOVOROSSIYA

- The Arbiter Of Europe’s Destiny.

- The House Dolgorukuy

- Madame Krüdener

- Ekaterinoslav

- The Arabat Arrow

- The Mystery Of General Inzov

- The Doukhobors

- Pushkin

- Chuguev Military Settlement

- “The Blessed”

- The Decembrists

- Penza

- Independence

- Last Words Of Samuel Khristianovich Kontenius

- “Amid Coffins And Desolation”

- Rusalka

- Dead Souls

- Secret Passages

- Astrakhan

- Nevsky Prospekt

- Kalmyk Ulus

- Love And Ambition

- Duellistes

- Pyatigorsk

- A Heroine Of Our Time

- Winter Palace

- Zeneida R-Va

- Steppes

- Letter To Natalya

- Fire And Ice

SOURCES:

[1] Bennett, Richard E. 1820: Dawning Of The Restoration. Brigham Young University. Provo, Utah. (2020): 57‒80. [Chapter Three: “Tsar Alexander I: The King Of The North And His Holy Alliance.”]

[2] Staples, John R. Johann Cornies, The Mennonites, And Russian Colonialism In Southern Ukraine. University of Toronto Press. Toronto, Canada. (2024) 48-76. [Chapter Three: “A Public Life, 1818–1824.”]

[3] Sherman, James. Memoir Of William Allen. Henry Longstreth. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1851): Frontispiece; Grellet, Stephen. Memoirs Of The Life And Gospel Labors Of Stephen Grellet: Volumes I & II. Henry Longstreth. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1860): Frontispiece.

[4] G. Hijo (C.A. Griscom, Jr.) “Quakerism And Theosophy.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. II, No. 4 (April 1905): 157-162.

[5] “The Emperor Alexander And The Quakers.” The Saturday Magazine. Vol. I, No. 24. (December 15, 1821): 553-555.

[6] Zorin, Andrei. By Fables Alone: Literature And State Ideology In Late Eighteenth And Early Nineteenth- Century Russia. Academic Studies Press. Boston, Massachusetts. (2014): 268-269.

[7] Pesenson, Michael A. “Napoleon Bonaparte And Apocalyptic Discourse In Early Nineteenth-Century Russia.” The Russian Review. Vol. LXV, No. 3 (July 2006): 373-392.