A Tournament Of Shadows

I. The Third Rome

The Roman Emperor, Constantine the Great, converted to Christianity. With the Edict of Milan in 313 C.E., the beleaguered cult from Palestine was made the religion of the Empire. Eleven years later (324 C.E.) Constantine moved the capital of the Roman Empire to the Greek city of Byzantium which he renamed Constantinoupolis, or Constantinople. At the inauguration of the “New Rome” the Emperor declared that no pagan rites should ever be performed within her walls. Constantine then summoned the first General (Ecumenical) Council of the Church to the town of Nicaea in 325 C.E. These leaders of the various churches were made to agree on the standard theology of the Empire, the articles of faith which became the Nicene Creed.[1] In 476 C.E. the (Latin) Western Roman Empire fell, leaving only its (Greek) Eastern half as its dwindling remnant.

Cut off from Byzantium, the West established a new Roman Empire of their own. On Christmas Day, 800 C.E., Pope Leo III crowned the Frankish king Charlemagne the Holy Roman Emperor. This was based on the concept of translatio imperii, a metahistorical belief that stated imperial authority could be transferred from people to people and place to place (such as Greece to Rome, or Caesar to Tsar/Czar.) Though Charlemagne sought recognition from the ruler of Byzantium, his mission was without success. The middle of the ninth century was a period of intensive missionary activity for the Church, which now turned its attention to converting the Slavs.[2] These European peoples of the East had long been despised by the nations of the West. These people, the Schiavoni, were known by the Latin West as “Esclavons,” or “Slavs.”[3]

Among these people there were the “Rus.” Some believed they were the descendants of Swedes, while others believed they were Slavs who lived to the south of Kiev since prehistoric times.[4] The hagiography of the Rus claimed an origin of three brothers, Rurik, Sineus, and Truvor belonged to a clan of Varangian Norseman (like the Swedes, Danes, and Norwegians) who were invited to rule a group of leaderless Slavs in North Eastern Europe. They chose as their center the city of Novgorod. Rurik, the last of the aforementioned brothers, died in 879 C.E. Prince Oleg became regent for the son of Rurik, Prince Igor, who was then only a minor. Oleg left Novgorod for the city of Kiev, along the Dnieper River, taking Igor with him. Kiev at the time was ruled over by Askold and Dir, two brothers who had driven out the Khozars. The brothers were former bodyguards of Rurik, but Oleg killed them on the grounds that they were not of noble blood and did not have claim to rule. Oleg decided to stay and issued the proclamation: “This will be the mother of the Russian Towns.” Prince Oleg ruled Kiev until 912 C.E. and was succeeded by Prince Igor who died in 945 C.E. Igor’s son, Svetoslav was a skilled knight who once invaded Byzantium.[5]

The missionary work of the Church among the Slavs began with the monks Cyril and Methodius in 863 C.E., when they ventured into Moravia at the bequest of Prince Rostislav. Here they clashed with German missionaries, but while the emissaries from the West conducted their services in Latin, Cyril and Methodius spoke in Slavonic. It was they who gave the Slavs the Cyrillic (Кириллица) alphabet. In subsequent generations, the missionaries of the Greek Church made greater inroads in this region, penetrating Serbia, Bulgaria, and eventually Russia. Around 988, Prince Vladimir (Svetoslav’s successor) converted to Christianity, and married Anna, the sister of the Byzantine Emperor. Prince Vladimir set out to Christianize his realm; priests, icons, relics, calendar, and other sacred accoutrement were imported, and mass baptisms were held in the rivers. The great idol of their ancestral god, Perun, was even rolled down the thill atop Kiev. Vladimir died in 1015, after which Yaroslav the Wise continued his father’s traditions. Not long after, doctrinal differences fractured the spiritual unity of the Church, resulting in a schism in 1054 C.E. The Byzantine Church, or Orthodox Church, would have its headquarters in Constantinople. The Latin Church (Catholic Church) would be headquartered in Rome. The Kievan State began to decline in the eleventh century, fracturing into principalities of rival power. Its strength was further weakened by the decline of the Byzantine Empire, eventually falling to the Tartars in the thirteenth century.

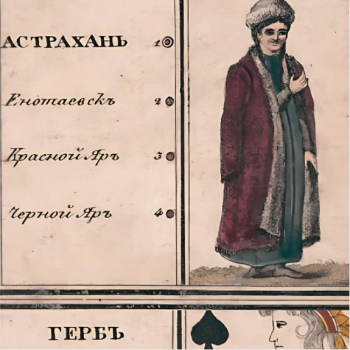

The groups of Russians who escaped the destruction of Kiev made their way into the dark forests of the north, principally in Nizhny Novgorod and Moscow. The Kievan Rus became Muscovite Rus, taking on traits that were “eastern and despotic” to buttress their survival. After being laid waste by the Tartars, Kiev fell under the power of Lithuania, and later Poland, and the land gradually took on the appellation of “Little Russia.” Under the successive rule of Lithuania and Poland, the Kievan Rus understood themselves as a new people, “Ukrainians,” (“people of the borderland.”) This identity was further informed by a people who emerged on the frontiers of Poland and Moscow. Oppressed by the Poles, a good number of the “Little Russians,” particularly the unmarried young men capable of bearing arms, formed themselves into a people known as Cossacks. They wandered forth to settle in various political societies in the desert steppes at the mouths of the Dniester, Don, and Dnieper.[6] There they fought and plundered, partly for their own benefit, and partly to pay tributes to Tartars, Turks, Poles, Moscow, and others. By degrees, these Cossack colonies spread over the whole steppe to the south as far as the Volga and the Ural.[7]

In the early centuries of its existence, the Russian Church remained in canonical dependence on the mother Church in Byzantium, and its head had to be appointed or at least confirmed in office by the Patriarch of Constantinople. Gradually, however, this dependence grew weaker and weaker, and since the destruction of the Byzantine Empire by the Turks in 1453, the Russian Church, for all practical purposes, became an independent national Church.[8] Constantinople had fallen, and with it, the doorway to the past had closed. By the end of the fifteenth century, a new world was emerging, one which saw the discovery of America and the rise of Muscovite Russia. On the verge of becoming a great power, Muscovy evolved her own politico-religious ideology emancipated from foreign tutelage. This ideology was predicated in the claim that Moscow was the “Third Rome” and, as such, a successor to the political and religious position once held by the Roman remnants of Constantinople.[9] This “Russian messianism” began with a series of letters composed in the sixteenth century by a monk from Pskov named Filofei. Specific importance was attached to a letter believed to be written to Ivan III, the most cited passage of that particular epistle stating:

So be aware, lover of God and Christ, that all Christian empires have come to an end and are gathered together in the singular empire of our sovereign in accordance to the books of prophecy, and this is the Russian empire: because two Romes have fallen, and a third stands, and a fourth there shall not be.[10]

Like the Western Church during the Middle Ages, the Russian Church had accumulated an enormous wealth of land which mostly belonged to the monasteries. Early in the sixteenth century a small group of church reformers, the “Trans-Volga Elders,” emerged from the hermitage of Sorsk (a respected center of ascetic monasticism.) Led by the ascetic mystic, Nilus of Sorsk, they called upon the church to abandon its worldly possessions so it may achieve the Christian ideal of poverty and humility. On the other side stood the “Josephites,” a larger group that enjoyed the support of the Church hierarchy, and who believed that the material wealth of the Church was an indispensable condition for its successful performance. The head of this faction, Joseph of Volokolamsk, was the abbot of one of the most affluent and influential monasteries in Muscovy which was known as the “nursery of bishops” throughout the sixteenth century. (Some of the most prominent divines from this period received their training there.) The Josephites stood for a strict adherence to tradition and emphasized the importance of ritual. The followers of Nilus, on the other hand, represented the growing spiritual trend in Russian Christianity of personal piety, and supporting a much more liberal policy regarding dogma and tradition.

The Josephites wanted the Russian Church to be in an indissoluble alliance with the State and expected a full measure of state-sponsored support and protection in return. The Trans-Volga Elders rejected compulsion in matters of faith. The realm of the Church was distinct from that of the State. The State, in their opinion, had no right to interfere in matters of the Church, just as the Church had no business meddling in politics.

The Russian government of the period was interested in this controversy within the Church, especially those which concerned with the problem of church lands. Muscovite rulers at this time were reorganizing the system of national defense in their dominions, establishing a principle of land grants in exchange for military service. To accomplish this, the government needed a large land fund at its disposal and consequently viewed the growth of church landownership with alarm. Regarding this issue, the government’s views were in alignment with the followers of Nilus of Sorsk who demanded the Church voluntarily relinquish its worldly possessions. On the other hand, the government was in full sympathy with the traditionalism of the Josephites (particularly their championing of a close alliance between Church and State.) An unwritten concordat was eventually concluded between the Moscow government and the Josephites of the Russian Church. The government abandoned its plan of secularizing Church estates, and in return, it received the unqualified allegiance of Church hierarchy. The opposition movement within the Church was effectively silenced. The Orthodox Church would finally become the official national Church of Russia.

This independence was given formal sanction with the elevation in 1589. The Russian Metropolitan was elevated to the dignity of the Patriarch of Moscow, recognized now as an equal by the other Eastern Patriarchs. Theoretically, the Church was free to choose its head, but from the outset, these elections were controlled by the State. It was customary to submit the names of the candidates for the Tsar’s preliminary approval, and with few exceptions, the Patriarch certainly did not feel himself to be the Tsar’s equal.

The first of these exceptions was Patriarch Philaret who was virtually co-regent with Tsar Michael (the first Romanov Tsar.) Philaret owed his exalted position to the fact that he was the Tsar’s father. A similar position was attained by Patriarch Nikon two decades later who also acted as the Tsar’s co-regent. Nikon overstepped his boundaries when he endeavored to advance in Russia the medieval Latin doctrine of the supremacy of the spiritual over the secular power. He was not supported by the Church in this claim, and Nikon was deposed by a church council and died in disgrace.

Tsar Peter The Great thoroughly reorganized the central administration of the Church during the beginning of the eighteenth century, seeking to eliminate any possibility of parallel authority in the State. Realizing the threat that a charismatic Patriarch might potentially pose to the unity of imperial control, the office of the Patriarch was abolished, and in its place, an ecclesiastical body called the Synod was established in 1721. The members of this Synod (chosen from among the bishops,) were appointed by, and responsible to the government, tasked with watching over the interests of the state. A lay official, known as the High Procurator (Ober Prokuror,) was also attached to the Synod, and over time would prove the real head of church administration.[11] Under this new scheme, church affairs could be managed in the same manner as any other branch of governmental business. The Russian Church had entered the modern period without the power it possessed in former times, and further weakened by the internal schism caused by Nikon’s reform. This resulted in the permanent secession of millions of “Old Believers” who refused to accept the “Nikonian innovations” (among whom were some of the most devout church members.) At the same time, the Church lost many of its members to the several new religious sects that began to appear in the eighteenth century, and which met with considerable success among the masses of Russia. The rapid westernization of the upper crust of Russian society (and the corresponding secularization of Russian culture) further exacerbated the Church’s loss of exclusive influence in the intellectual life of the nation. An indifferent, somewhat hostile, attitude towards religion became commonplace among the educated upper class.

Then came Catherine the Great, the Prussian wife of Peter the Great’s grandson (whom she forced to abdicate in 1762.) It was during her reign that Imperial Russia gained substantial territory, extending its borders by 200,000 square miles. At the expense of the Ottoman Empire and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Russian Empire would absorb Belarus, Lithuania, Courland, Crimea, the North Caucasus, and the right-bank of Ukraine, and Novorossiya (the southern mainland of modern Ukraine,) which comprised the territories of Bessarabia and Transnistria, territory that once belonged to a confederation of Turkic nomads called the Nogai. Catherine wanted these sparsely populated steppes of Novorossiya cultivated, so she invited European settlers, among which included West Prussian Mennonites. The first of the Mennonites settled in Chortitza in 1789 on the banks of the Dnieper River near present-day Kherson. (A wealthier group would follow in 1804 to found the Molotschna Colony on the Molotschna River, displacing the nomadic Crimean Tatars who were removed by the Russian government.)[12]

Around the same time, Catherine’s “Greek Project” came into existence, and it was one of the most ambitious foreign policy ideas ever put forward by a Russian ruler. Central to this plan, co-conceived with Prince Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin (a Russian military leader, and statesman,) was the conquest of Constantinople. Catherine, however, did not intend to relocate the Russian capital to the “Second Rome,” nor did she intend to unite Constantinople with the Russian Empire. Constantinople was to become the center of a new Greek Empire, one whose throne would go to her grandson, Konstantin Pavlovich on the strict condition that he and his heirs would forever repudiate any pretensions to the Russian crown. Her other grandson, Alexander Pavlovich, was intended to inherit the Russian throne, and in this way, the two neighboring Orthodox powers would be united under the scepters of “The Star Of The North” and “The Star Of The East.” The poetic resonance of mytho-history was easily seen. Russia received its faith from the Greeks owing to the marriage of a Kievan prince and the sister of a Byzantine emperor; it could now position itself as the natural savior of the Greeks who suffered under the yoke of the “infidels” Ottomans. Russia was also framed as the daughter who was obliged to pay her debt to her elder (and simultaneously younger) sibling. Russia did not conquer Constantinople, but the sentiment nevertheless remained.[13]

SOURCES:

[1] Ware, Timothy. The Orthodox Church. Penguin Books. London, England. (1963): 26, 51-53,66-67.

[2] Ware, Timothy. The Orthodox Church. Penguin Books. London, England. (1963): 82-92.

[3] “Feeling themselves unqualified to lay claim to the culture of modern Europe, some Slavs have claimed that of the ancient world. Certain Serb and Bulgar writers have taken it into their heads to demand as their rightful patrimony the greater part of Greek civilization from Thracian Orpheus to Macedonian Alexander.” [Leroy-Beaulieu, Anatole. The Empire of the Tsars and the Russians. G. P. Putnam’s Sons. New York, New York. (1893): 97-99.]

[4] Pritsak, Omeljan. “The Origin of Rus.” The Russian Review. Vol. XXXVI, No. 3 (July 1977): 249-273.

[5] Shulgin, Basil. “Kiev, Mother Of Russian Towns.” The Slavonic And East European Review. Vol. XIX, No. 53/54. [The Slavonic Year-Book.] (1939-1940): 62-82.

[6] “Cossack” is an Old East Slavic loanword from Cuman, meaning “free man” or “conqueror,” and ethnonym, “Kazakh,” is from the same Turkic root. [Pritsak, Omeljan. “The Turkic Etymology of the Word ‘Qazaq’ ‘Cossack.’” Harvard Ukrainian Studies. Vol. XXVIII, No. 1/4 (2006): 237–43.]

[7] Kohl, Johann Georg. Russia: St. Petersburg, Moscow, Kharkoff, Riga, Odessa, The German Provinces. Chapman And Hall. (1844): 504-505.

[8] Karpovich, Michael. “Church And State In Russian History.” The Russian Review. Vol. III, No. 2 (Spring 1944): 10-20.

[9] Toumanoff, Cyril. “Moscow The Third Rome: Genesis And Significance Of A Politico-Religious Idea.” The Catholic Historical Review. Vol. XL, No. 4 (January 1955): 411- 447.

[10] Siljak, Ana. “Nikolai Berdiaev And The Origin Of Russian Messianism.” The Journal Of Modern History. Vol. LXXXVIII, No. 4 (December 2016): 737-763.

[11] Karpovich, Michael. “Church And State In Russian History.” The Russian Review. Vol. III, No. 2 (Spring 1944): 10-20.

[12] Friesen, Ralph. Between Earth & Sky Steinbach, The First 50 Years. Derksen Printers. Steinbach, Manitoba, Canada. (2009): 12-20.

[13] Zorin, Andrei. By Fable Alone: Literature And State Ideology In Late Eighteenth And Early Nineteenth- Century Russia. Academic Studies Press. Boston, Massachusetts. (2014): 24-27.