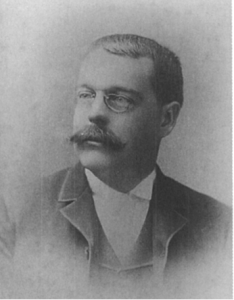

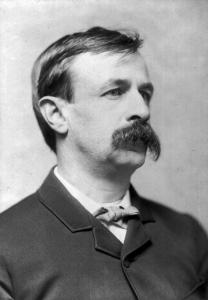

Sylvester Baxter, 1889.[1]

Sylvester Baxter (1850-1927,) a New Englander with a pedigree on both side which stretched back to the original Puritan settlers, was born on February 6, 1850, in Yarmouth, Massachusetts.[2] Though he would spend most of his life in Malden, Massachusetts, he always regarded himself a “son of the Cape.” When Baxter was born, his father was an active Freemason.[3] He attended several schools on the Cape (public and private) until he turned seventeen. When he was twenty-one, he left the Cape and moved to Chelsea, Massachusetts (a suburb north of Boston adjacent to Malden.) He wanted to attend the architecture school at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but could not afford the tuition.[4] Instead, he found work as a reporter on The Boston Advertiser in 1871. He was joined by his friend, Edward Page Mitchell (the future-editor of The New York Sun who had several encounters with the Theosophists during the Lamasery days.)[5] Baxter remembered, “Mitchell and I had started almost together as reporters on the Advertiser. We shared the same bed in a hall bedroom on Bullfinch Street.”[6] Baxter gravitated toward art as his specialty, and contributed poems to The Atlantic, Galaxy, The Century, and other magazines.

American universities at this time did not have a systematic course of graduate study, so in 1875 Baxter joined the group of young American men who went to Germany for higher education, studying at the universities in Leipzig and Berlin. He wrote extensively about German civics, and attended cultural events like the Wagner festival at Beyreuth. He then went to London with Frank D. Millet (just before Millet went as a journalist to the Russo-Turkish War in 1879.) When Baxter returned to America, he joined The Boston Herald.

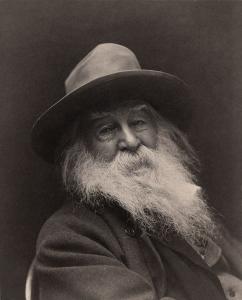

WHITMAN

Walt Whitman. (wiki)

Baxter met Walt Whitman in April 1881 during the poet’s second visit to Boston, “beginning a friendship that [would] always form one of the pleasantest memories of [Baxter’s] life.” Of Baxter, Whitman would state: “Sylvester is a quiet, sane, agreeable make of man—don’t get into flusters, don’t indulge in bad tempers about humanity—yet is radical, too, if not revolutionary, and looks for some shake-up in the social order before long.”[7] Whitman had been invited to Boston to read his paper on Lincoln by John Boyle O’Reilly and some younger admirers connected with the Papyrus Club. As a member of The Boston Herald staff, Baxter was asked to write an article on Whitman—“not an interview, but one of those personal sketches of literary and public persons that had become a feature of [The Boston Herald.]” Baxter writes:

Whitman was strongly impressed by the growth of Boston, not only materially but in the higher aspects. He compared the change to the facts revealed by Schliemann in his excavations, where he found superimposed remains of cities, each representing either a long or rapid stage of growth and development, different from its predecessor, but unerringly growing out of and resting on it. “In the moral, emotional, heroic, and human growths (the main of a race in my opinion), something of this kind has certainly taken place in Boston,” he wrote […] The contrast with the Boston that he knew on his two former visits must indeed have been remarkable. It was then in the last stages of its hereditary and traditional Puritanism; it was now the least Puritanical of all the great American cities so far as the native social element, that which distinguishes them as American, was concerned. The ferment of its intense radicalism, generated by its very Puritanism, had liberalized, and transformed it.[8]

~

Working for The Boston Herald, Baxter traveled as a correspondent to Mexico and the American Southwest. In the decade after the Civil War, the financial interests of Boston were focused on the railroad developments beyond the Mississippi. The image of the Arizona Territory had changed from one of backwardness to one of promise. The Rev. Edward Everett Hale, “dean of literary Boston,” was among those who championed further scholarship on the region.[9]

Here there is an overlap with Theosophical Society history. In 1878 Blavatsky’s critics attacked her scholarship on the Toda people of the Blue Hills.[10] Charles Sotheran responded with a testimony of Major Alfred R. Calhoun (Chief of the U.S. Government Survey of the 35th Parallel.)[11] As Sotheran pointed out, Calhoun had encountered “a similar caste among the Zuni Indians of Arizona […] who were as white as himself, and with blue eyes and fair hair.” These people were regarded as sacred and “set apart from birth with a religious veneration.”[12] In 1881 Baxter met with the anthropologist, Frank Hamilton Cushing, who was then living among the Zuni of New Mexico.[13] While staying with Cushing, Baxter learned of a Zuni legend concerning these fair-skinned people:

Many of the beards were of a pale Scandinavian blonde, while the hair was of the same color in a number of instances. Perhaps these might have represented mythological characters who were albino. But the albinos had no beards. Is it not possible that they may point back to a time when a light haired and bearded race existed in America?[14]

A few months later, in February 1882, Cushing made waves in America by hosting a delegation of Zuni in Boston, where they performed their rituals for the benefit of Boston city leaders, clergy, and Harvard professors.[15] Baxter writes:

A memorable day was spent at Harvard University. A visit to the Peabody Museum of Archeology resulted in the discovery by Mr. Cushing of a close relation between the religion of the Incas of Peru and that of the Zunis. That afternoon there was an athletic tournament by the Harvard students in the gymnasium, at which the Indians were fairly beside themselves with delight at the performances. They maintained that the dents must be members of a “Grand Order the Elks,” an athletic order of the Zunis, since to achieve such skill, they must be inspired by the gods.[16]

“Every aesthetic person knows that the further back in the world’s history we go, the better do things become,” The New York Times mockingly stated. “Boston has something better than early English or even the Italian Renaissance. It has the Zuni religion.” The age of the Zuni was inferred by their “strange and mystic” rituals, suggesting a time for the start of their civilization that was at odds with contemporary scientific consensus.[17] The article added:

If Col. Olcott and Mme. Blavatsky had stayed in the United States, instead of going to India in search of the true faith among the Brahmins, they might have found a religion more truly bric-à-brac than anything they will discover in Bombay. As it is, Boston has secured this inestimable boon, and is at this moment in possession of a faith as ancient, if we may believe the missionaries, as the American continent.[18]

Coinciding with the arrival of the Zuni, Ignatius Donnelly published his popular, Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, in which he claimed for America the lost kingdom mentioned by Plato.[19] On March 18, 1882, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle devoted several columns to a review of Atlantis, and suggested that the Cushing’s research on the Zuni gave credence to Donnelly’s North America-Atlantis theory.[20]

“The First Sight Of The Atlantic, At Boston.” From Baxter’s “An Aboriginal Pilgrimage.”

~

In August 1882 Whitman arrived in Boston and wrote to Baxter asking him if he could “find him a quiet boarding-place where he could stay several weeks while he was overlooking the publication of the complete edition of his poems by the house of James R. Osgood & Company.” Baxter found him a pleasant room in the Hotel Bulfinch, “and during the two months of his stay felt himself comfortably at home.” Baxter describes some incidents he experienced with Whitman at this time:

An episode that gave Whitman rare pleasure was a visit to Concord as a guest of Frank B. Sanborn, meeting Emerson for the first time after many years. It was delicious autumn weather, and that evening many of the Concord neighbors, including Emerson, A. Bronson Alcott, and Miss Louisa M. Alcott, filled Mrs. Sanborn’s back parlor. The next day, Sunday, September 18th, he dined with Emerson and spent several hours at his house. He also visited the “Old Manse,” the battle-field, the graves of Hawthorne and Thoreau in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, and the site of Thoreau’s hermitage at Walden Pond. Another pleasant incident was a roadside chat with Dr. William T. Harris, the scholar and philosopher, as he halted in front of his house on the drive back from Walden Pond. This Concord visit is charmingly described in “Specimen Days.”[21]

Baxter would write enthusiastic reviews of Whitman’s work in the Herald, and raised money to support the “good gray poet,” in his twilight years in Camden, New Jersey.[22] Baxter became interested in Theosophy in spring of 1885 (along with a few other people who “casually discovered that they had mutually had an interest in Theosophy.”) Informal meetings were held until the end of that year. Baxter officially joined the Theosophical Society on December 17, 1885[23] Ten days later (December 27, 1885) a provisional charter was granted by the American Board of Control for the creation of a Theosophical Branch in Malden, Massachusetts.[24] Assistance was given by Arthur Gebhard and two Bostonians who belonged to the Rochester T.S., Charles R. Kendall, and Hollis B. Page.[25] George D. Ayers was among the founding members.

Sylvester Baxter, 1885.[26]

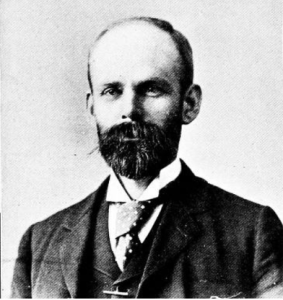

AYERS

George David Ayers (1857-1933) was an “exceedingly nervous gentleman with bushy, red whiskers.”[27] Born in Boston, Massachusetts, Ayers was “descended on both sides from early colonial stock.” When he was eighteen-months-old he was taken by his parents to Malden, Massachusetts, where he would live the majority if his life. He received his early education at Malden public and high schools, where he graduated in 1874. He entered Harvard College in 1875, where his main interests were philosophy and political economy. On leaving college in 1879, Ayers entered the Harvard Law School, where he graduated with the degree of LL.B. in 1882. He continued his legal studies in Boston in the office of William Gaston, the former Governor of Massachusetts. Ayers was admitted to the Suffolk Bar in February, 1883, and in March of that year he began active practice alone in Boston. He wrote numerous papers on politics, economics, and was active as a speaker in the Cleveland campaigns (of 1884 and 1888.)

George D. Ayers.[28]

In January 1885, he married Charlotte Elizabeth, they would have one child, a boy also named David. Later that year he formed a co-partnership with George Clarendon Hodges under the firm name of Ayers & Hodges (later Ayers, Hodges & Day by the admission of Stanton Day.) It was at this time that Ayers became actively interested in the Theosophical Movement in 1885, when he joined the Malden Theosophical Society as a charter member, on December 17, 1885.[29] It was said that Ayers would charge someone “for every five minutes you talk with him on legal subjects,” but on the subject of Theosophy, he would talk “by the hour and charge you nothing.”[30]

Baxter would make the claim that Whitman was a Theosophist, and told him as much.[31] “Even the Theosophists claim me. How much of me is going to be left for myself after all the claims of the radicals are satisfied?” Whitman would state. “[Baxter] is one of my cordial, truest friends—an out and out assenter to the Leaves: radical, progressive, with lots of look ahead. Baxter has gone off into Theosophy: all our rebels go off somewhere.”[32] (Whitman already had connections with the Theosophists George Chainey and Gopalrao Joshi, the latter whom he met at the time of the creation of the Malden T.S.) Baxter wrote to Whitman on December 6, 1886:

I have been thinking very often of you lately, and wishing that something might be done to lighten life for you. The nation is deeply in your debt for the services you rendered in the war, not to mention its deeper debt to you as a poet which will be appreciated more and more as the years go on […] Some of us, friends of yours here, are proposing to organize, on a broad and simple basis, a Whitman Society, to promote an interest in and study of your works. I believe it may accomplish much good […] In the December number of The Path, a magazine published in New York, is one of a series of articles on “Poetical Occultism.”[33] This one is devoted to some of your poems and is partly written by me, partly by my friend W. Q. Judge.[34]

WILLARD

Another Boston Theosophist, Cyrus Field Willard (1858-1942,) would meet Whitman at this time. Born in Lynn, Massachusetts, Willard moved with his family to South Boston in 1866.[35] He received his early education at the Bigelow Grammar School, becoming fluent in German. After his schooling he worked as a reporter for The Boston Globe.[36] It was a field which he believed had a responsibility to moral uplift.[37] Willard states that he was “a friend and pupil of [W.]Q. Judge since 1886,” and attended the meetings at [Helen] McCoy’s house on West Newton St.,” but because of his night work on The Boston Globe, he “could not be present at the meetings of the Branch very often.”[38] (Despite his early involvement, Willard did not join the Theosophical Society until December 1889.)[39]

Proficiency in German allowed Willard to attend socialist meetings in the Boston, gaining an insight into the emerging political trends.[40] This is alluded to in an interview he had with Walt Whitman that was published in the December 1887 issue of The American Magazine.[41] Willard predicted that Boston would soon have a Democratic mayor. The four reasons why he believed so provide insight into the political environs into which he would delve with the Nationalist Club:

First, the Democratic organization is rapidly approaching perfection; second, the so-called temperance party is crazy to sting the Republican bosom that warmed it; third, a long lease of power has bred bitter factions in the Republican camp. Fourth—and most important—the Labor Party and the party of Progressive Socialism are rapidly increasing. The city of Boston today is simply honeycombed with subterranean societies, who don’t yet know quite all they want, but are bound in the near future to get some things.”[42]

Willard would come to regard Socialism as “the instrument to bring about Universal Brotherhood.”[43] His political leanings would also influence his cousin, Frances Willard, founder of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (who interviewed Blavatsky herself in the 1870s.)[44]

Baxter, meanwhile, had embarked on the Hemenway Expedition with Cushing.[45] He recorded a narrative of the expedition in the pamphlet, The Old New World. With regard to this expedition, Blavatsky would state that Baxter was “doing good theosophical and anthropological work.”[46]

BRIDGE

John Ransom Bridge.

From The Boston Sunday Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) September 17, 1893.

In 1887 John Ransom Bridge (1858-1904,) replaced C.R. Kendall as the Boston Branch President.[47] Described as a tall, handsome, man with a big, black, beard, Bridge had dark lines under his eyes, and a repose that was unmistakably “distingue.”[48] Born in Oneida, New York, Bridge was reared a Baptist, but believed since childhood that “he had existed before.”[49] His early years were spent in his native state of New York, and before deciding on college, he went out West to work a year on a sheep ranch on the Rio Grande. When he returned to the East, he found work setting type on The Hornellsville Times (Hornellsville, New York.) He then became editor of The Hornellsville Tribune (Hornellsville, New York.) In 1879 he enrolled in Union College (Schenectady, New York,) but transferred to Harvard College in 1882, joining the class of 1884. After taking his degree at Harvard, Bridge entered the business world. He had an office in the Studio Building (110 Tremont Street) where he opened a “school supply” business as well as a teachers’ agency known as the Eastern Teachers Institute. He was also a book publisher, but this line of work was primarily relegated to the topics of teaching and education, such as The New England School Guide[50]

It was said that the Boston T.S. “discouraged the childish desire for mere phenomena,” and spent their time discussing ethical problems, “seeking each in his own soul alone the solution of the Sphinx’s riddle.”[51] Bridge’s letters to W.Q. Judge during this period seem consistent with that reporting. Judge writes to him at this time: “It would seem wise to be acquainted with these before hazarding acceptance of such tales or attempting trials of our own.”[52] At this time Herbert Richardson was Vice-President, and Edward Noyes (one of the founders of the Malden Branch) was named Secretary.[53] Dr. Ami Brown, who joined the Society in 1875, was another important member.[54] Another “big” name was United States District Attorney, George M. Stearns, who joined the Boston Branch five months after prosecuting Alexander Graham Bell for fraudulent patents. (Bell won the case.)[55] Their meetings were held in the Parker Memorial Building on Berkeley Street.[56]

From 1888 until her death, Bridge had “considerable correspondence” with Blavatsky. The letters of which Bridge described as “always interesting, generally bizarre, showed a keen knowledge of human nature, particularly its weakness, and an utter contempt for Blavatsky worship; though for the ‘cause’ she apparently was always ready to sacrifice anything and anybody, herself not excepted.”[57] On the question of masters and adepts, she gave Bridge the following advice for finding them: “Adepts here, adepts there—please oblige me and look well into your boots tonight to see whether you will not find, perchance, an adept stuck to the soles somewhere.”[58] A letter from Blavatsky from September 1888 seems to continue along the lines which he presumably asked Judge.[59] In response to a protest against “tying the society to her apron-strings,” Blavatsky wrote to Bridge:

So far as the “Founders” are concerned, depend upon it they will do their best to obstruct any tendency to “hero-worship.” […] The first patient upon whom the prescription worked was my colleague Olcott, who at the beginning was quite ready to forget the Cause for the production of phenomena, the “Grand Principle” for the miserable personality he almost worshipped, as the Master’s agent. And he is so thoroughly cured that now he is as ready to dress my hair with a curry-comb as he was ready before to kiss the hem of my Tibetan Robe.[60]

LOOKING BACKWARD

Looking Backward. (wiki)

In the late 1880s a science-fiction “Social Gospel” novel appeared in the form of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888,) a Utopian Rip-Van-Winklesque story set in the year 2000 which told “the progress of the last one hundred years.”[61] Highly influential, it inspired “Nationalists” clubs across America which aimed to create the semi-Socialist civilization portrayed in the book.[62] Willard was instrumental in creating the first National Club in the United States. On June 28, 1888, Willard wrote to Bellamy: “I have been thinking that it would be a good idea to organize an association to spread the ideas contained in your book. What do you think of it?” Bellamy replied, “Go ahead by all mean and do it if you can find anybody to associate with.” With this encouragement, Willard and fellow Theosophist, Sylvester Baxter, set out to organize a Nationalist Club in Boston.

Edward Bellamy. (wiki)

By August, the club was well under way. Personal affairs prevented Willard from committing fully to the group, and Sylvester Baxter, a participant on Hemenway Expedition with Cushing, was not even in the city.[63] The small group, faced with disintegration, merged with General A. F. Devereux’s Boston Bellamy Club in September 1888. A new group was formed to “revolutionize the social fabric,” of America.

A committee consisting of Cyrus Field Willard, Gen. A. F. Devereux, Sylvester Baxter, Rev. W. D. P. Bliss, and Charles E. Bowers was formed, who named the group the Nationalist Club of Boston, and adopted a Constitution and Declaration of Principles at a meeting on December 8, 1888.[64] On December 15, 1888, officers were elected. Edward Bellamy, who was present at this meeting, was elected first Vice President. George D. Ayers was the first President.[65] (W.D.P. Bliss found the club to be too secular and organized another club in 1889 called the Society for Christian Socialism.)[66] By January 1889 the club had fifty active members.[67] Of the elected officers, at least five were known Theosophists (Ayers, Bridge, Willard, Baxter, Noyes.) Charles Bellamy, Edward Bellamy’s brother, would charter the Springfield T.S. (Springfield, Massachusetts,) on July 10, 1891. [68] Another officer, Edward Stanton Huntington, would join the Theosophical Society in 1890, and write the Theosophically-themed work, Dreams of the Dead (1892.)[69]

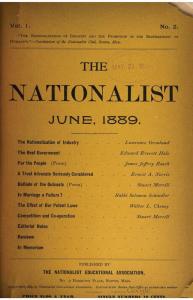

The Nationalist. (iapsop)

Willard, who would write a regular column for the organizations journal, The Nationalist (1889-1891,) also wrote about Nationalism for Theosophical journals.[70] An article in the March 1889 issue of The Path makes an explicit case for the harmonious connection between the Nationalists and the Theosophical Society. Baxter (writing under the name “Sylvanus”) writes:

It is a favorable omen that the pioneer Nationalist Club has been organized in Boston, the birthplace of the American Nation, and also of the movement that resulted in the abolition of negro slavery. When industrial slavery is abolished, human freedom will first be realized. It is also significant that several earnest Theosophists should have been drawn to the movement at the start, and there encountered others theosophically inclined. The change may be nearer than many think. The end of a cycle is at hand. The wheel of evolution is revolving rapidly now. It may be observed that the end of the Kali Yuga, and the dawning of the age whose conditions shall evolve the Sixth Race upon our continent, have not been predicted for the distant future. Changes, for which scores of centuries have slowly been preparing, may be accomplished in a few swift flying years when the conditions are once ripe.[71]

J.R. Bridge writes in Lucifer:

What the Theosophists expected was to use the enthusiasm aroused by Mr. Bellamy’s book, Looking Backward, as a means of sowing broadcast the idea of universal brotherhood and the organic unity of all mankind. In the accomplishment of this work, preacher and Dives alike came to their aid. For months the doctrine of brotherhood and the nationalization of industries was labored over in nearly every paper and pulpit in the country. The end is not yet. It does not matter that the most of this labor was adverse criticism. Seed has been planted, much of which in distant time must bear a bountiful harvest. Thoughts lie dormant, sprout, and grow, as do seeds and plants in what we are pleased to call the natural world. Thus does opposition sometimes work for the very end it opposes. So also, says an old occult doctrine, does everything return to its source, the significance of the circle, as priest and plutocrat may discover, when too late, of their efforts to retard the mighty wheel of social evolution. How strange that the lessons of history, like the past experiences of the individual, so plain to be read, should be ignored until the hand of Fate has written the judgment in fiery letters and the day of reconsideration is past.[72]

Ayers, already a member of the Executive Committee of the Young Men’s Democratic Club of Massachusetts, was an ardent supporter of the principles laid down by the Nationalist Party, and in 1889 and 1890 was first President of the Nationalist Club in Boston.

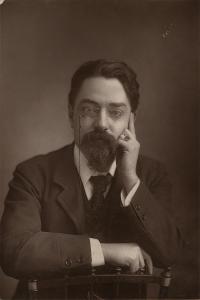

Sidney Webb (wiki)

BLISS

Another member of the Nationalist Club that deserves attention was the Rev. William Dwight Bliss. Born in Constantinople of American Missionary parents, Bliss fell under the spell of Fabianism during his many trips to London. When Sidney Webb and Edward Pease spent twelve weeks in America in the autumn of 1888, they found Bliss to be a zealous supporter. Bliss would be carefully prompted by Sidney Webb (who attended the December 15, 1888 meeting of the Nationalist Club incognito.)[73] Given the timing, one can’t help but notice a certain pattern. Earlier that summer, before coming to America, Sidney Webb attended the same Fabian Society meeting with Annie Besant, and George Bernard Shaw, which resulted in the Match Girl Strike.[74] Besant, an avowed Socialist, would famously join the Theosophical Society in 1889. Bliss would come to be regarded as the founder of Fabianism in the United States. As mentioned above, Bliss found the Nationalist Club to be too secular, and organized another club in 1889 called the Society for Christian Socialism. Though an Episcopalian, Bliss operated an interfaith mission parish in 1892, the “Brotherhood of the Carpenter,” where laborers could discuss practical social efforts.[75] As Bliss stated: “We especially invite those who do not believe in the Church, be they rich or poor.” At these meetings, Bliss would hold “Brotherhood Suppers,” providing cheap meals. But, as Bliss noted, people called the movement “too socialist for the Christians and too Christian for the socialists.”[76] In 1894 an ex-Methodist divine, and Christian Socialist named Herbert Casson would establish the Labor Church in Lynn, Massachusetts, inspired by Bliss’s model.[77]

GRIGGS

Arthur Burnham Griggs (1856-1899,) another name associated with the Nationalist Club, was born in Mansfield, Connecticut, to Dr. Oliver B. Griggs and Anne E. Griggs.[78] A tall, stout, young man who wore “scholarly spectacles,” he received his early education at the Highland Military School (Connecticut.)[79] In speech Griggs had an abrupt, business-like tone and address.[80] He joined the Theosophical Society of the Arya Samaj in 1878 when he was just twenty-two years old.[81]’[82] (Griggs was also a Mason, and for many years a member of Willimantic Lodge, Connecticut.)[83] It was said that Griggs was one Blavatsky’s earliest and best friends, and that Blavatsky “was like a mother to him.”[84]

For some time Griggs was the town clerk and treasurer of Windham, Connecticut.[85] By the 1880s, however, he was working as an agent for the American Electrical Manufacturing Company of New York, which had been responsible for illuminating the Statue of Liberty since its dedication.[86] Griggs’s name does not feature predominantly in Theosophical literature until the fall of 1888, when he joined his friend, John Ransom Bridge, in his investigation of Hiram E. Butler and the G.N.K.R.[87]

At the same time the Nationalist Club was being established, the scandals surrounding Hiram Butler’s Society Esoteric was raising eyebrows in Boston. After reading Butler’s The Call To The Awakened, Bridge and his friend, Griggs, set out to investigate the matter. They received a letter from Blavatsky on January 1, 1889, in which she repudiated the G.N.K.R. as a “bumptious piece of charlantry and a humbug on the face of it.” Blavatsky’s decree of disapproval was sufficient enough for Bridge and Griggs to visit Butler and put an end to the matter.[88]

In 1889 Griggs was elected President of the Boston Branch of the Theosophical Society (a position he would keep until 1892.)[89] Under his leadership, the Branch had a period of steady growth. This “renewal of Boston” was “due distinctly to [Griggs’s] energy,” The Path noted.[90] It was Griggs who formally charged Dr. Elliott Coues of “un-Theosophic conduct,” on June 11, 1889. Judge officially sent a copy of the charges to Coues in a registered letter, notifying him of the date when the Executive Committee would be prepared to hear his defense. During the intervening time no reply was received, and the Committee, having considered the charges, adjudged them sustained, by a unanimous vote, and expelled Coues from the Theosophical Society on June 22, 1889.[91] When Bridge elected to resign from the Presidency of the Boston Branch, it may have been due to some jealousies on the part of Griggs, his successor. In the summer of 1889, Bridge sent a private letter to Blavatsky in which he hinted that she should make Griggs a Councilor of the Esoteric Section (E.S.) instead of him as Griggs seemed “jealous of him.”[92] Regarding his involvement with Theosophy at this time , Willard writes: “I backed [Arthur] Griggs to take our rooms on Boylston St. and helped to elect Griggs as President of the Boston Branch and we elected Crosbie as Secretary [in 1889.]”[93] His talks before the Theosophical Society Branch meetings during this period focus on the dangers of hypnotism. “Pregnant of evil as it is, it must be popularized, even at the risk of running modern society on the rocks of black magic,” he stated.[94]

In July 1890 the Boston Branch moved to a 40×20 room on the second floor of 66 Boylston Street.[95] It was decided to hold regular public meetings every Thursday evening on such subjects as hypnotism, white and black magic, thought transference, electrical differentiation, karma, reincarnation, the work of Sanskrit and Hindoo writers, and other similar matters will be discussed.[96]

It was at the Hotel Boylston where a memorable Theosophical Convention with Annie Besant was held in April 1891.[97] Willard writes: “I was there in the capacity of a member of the Boston Branch […] as well as a representative of The Boston Globe on which I held an editorial position whose duties then precluded my being a delegate as I had been before […][98] It was during this Convention that Willard (and others) allegedly witnessed W.Q. Judge shape-shift before their eyes.[99] Days after the Convention, on May 7, 1891, Griggs married Sarah “Sadie” Tape.[100] Blavatsky died the following day. Sadie recollects: “[Griggs] had a chart of the stars for [the wedding] date and it said that he would die of kidney trouble in eight years […] He knew he was going to die, but he said, “Never mind, I’ll come right back to you.”[101] In 1892 Griggs “went out” of the Theosophical Society. The details of this even remain unclear, but Cyrus Field Willard’s testimony gives us a bit more insight:

When Griggs “kicked out” in 1892 and Judge came over from New York to settle that trouble he blowed me up for not stopping it; he asked me who we wanted as President, and I said “[Robert] Crosbie is as good as anyone.” He said then, “anyone you people here want is satisfactory to me.” So at the next meeting of the Branch I nominated and had Crosbie elected as President of the Boston Branch.[102]

1892 Baxter was made the first Secretary of newly-established Metropolitan Park Commission of Boston. His work envisioned an “Emerald Metropolis,” whereby Boston would integrate its public green-spaces holistically into the urban schema.[103] It was said that Boston’s subway system owed its existence more to Baxter’s “keen and ardent championship than to any other cause.”[104] In 1893 he would marry Lucia Millet, the sister of Frank Millet.[105]

For some years, beginning in the early 1890s, Bridge was associated with fellow Theosophist, E.I. K. Noyes, in bond dealing and investment securities under the firm name of Noyes & Bridge (53 State Street, Boston, Massachusetts.) In 1893 he severed that partnership and to create the firm of J. Ransom Bridge Co. His correspondence with The Boston Globe suggests Bridge was concerned Gold standard, and the global banking system in general.[106] On April 25, 1894, Bridge married Emma Frances Desmais Bugbee, and the two lived for some time in Boston’s Tremont Building.[107] In 1899 Bridge was “instrumental in exposing the Keeley motor fraud, in the interest of the public.”

Ayers’s law practice continued to developed primarily along the line of real estate matters, but in 1891, having lost his abstract books in the fire that destroyed the Sears building, he became Resident Attorney and Agent for the Lawyers’ Surety Company of New York. (He resigned a year later.) He was President of the Malden Branch from October 1891 to January 1894, when he declined re-election to become the President of the New England Theosophical Corporation when it was incorporated in November, 1893. From its headquarters at 24 Mount Vernon Street, Boston, Ayers launched a campaign that saw the successful propagation of Theosophy throughout the States of Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. The summer of 1894 William James consulted Ayers for insight into the Theosophical understanding of “personality,” while writing his entry, “Person and Personality,” in Johnson’s Universal Cyclopedia (1895.)[108] A week after corresponding with James, Ayers would be among the first lecturers at Sarah Farmer’s Greenacre Conference.[109] By 1895, the Theosophists in America desired autonomy from the international organization. Ayers was instrumental in drafting the resolutions for secession. Cyrus F. Willard writes:

It was George Ayers who suggested the historical sketch of the Theosophical Society from data he turned up in preparing his legal opinion and it was Louis Wade who read it and was put on the Committee on Resolutions in place of Crosbie, who as President of the branch where the convention was held was by custom entitled to the position. It was Ayer on whom Judge depended in that convention. It was Ayer, after Judge called the convention to order, who nominated Buchman as temporary chairman. It was Ayer “of Boston” who was put on credentials. It was Louis Wade of Malden Branch of which Ayer had been President who was put on the important Committee on Resolutions, whose report with legal opinion of George Ayer, was the all-important business of that convention, that caused the convention to declare its autonomy and the election of Judge as President for life.[110]

Returning to the overlap between Socialism, Christianity, and Theosophy, in Boston, it was in the summer of 1895 that Bliss’s influence is felt directly. When Ernest T. Hargrove lectured in Massachusetts in the autumn of 1895, he spoke before an “intelligent audience” at Casson’s Labor Church in Lynn, Massachusetts.[111] On the day of his arrival, Leoline Leonard and six other Theosophists decided to band together to devote their energies to giving a practical presentation of Theosophy to the working classes. Opportunities would be sought to lecture on Theosophy before labor organizations of all kinds. The Branch meetings would take the form of a training class, in which questions of the day would be discussed in the light of Theosophy, Socialism, Nationalism, and all the other solutions of social evils would be considered (as well as their limitations.) Their application for a charter was approved on September 30, 1895, under the name Beacon T.S.[112] Leoline was named Vice President.[113] James F. Morton, Jr. was named President, and Minnie Wade was named Secretary.[114] The Beacon T.S. was soon renting a room in Pressmen’s Hall (45 Eliot Street,) a building which labor unions, and working men’s clubs, used for their meetings.[115] Though different schemes were presented and considered, the most promising was the Sunday night “Brotherhood Suppers,” where cold cuts, tea or coffee, and cakes, were served. During these night, free to the public, a discussion would be held of any subject chosen for the evening.[116] This plan was advocated by Leoline who was inspired by a similar project conducted by Bliss (who published A Handbook of Socialism that same year.) [117]

Eliot Street & Columbus Ave. (Source: Wiki)

In January 1896, Charlotte Elizabeth Ayers died.[118] A month later W.Q. Judge would also die. That summer a global “Theosophical Crusade” was announced at the Tremont Temple (a Boston theatre.) In the days leading up to it, Ayers would tell the press:

The great Masonic body is a part of the Theosophical Movement, and will be called upon to help “the widow’s son”—the Orphan Humanity—just as they were called upon to help, and did help that branch of the Theosophical Movement which inaugurated the American Revolution. A High Mason gave Lafayette, for future use in the United States, a seal, which never, as yet, has been used. The design is that of the reverse side of the US great seal. It is a pyramid whose capstone is removed, with the blazing eye, in a triangle over it, dazzling the sight; above it are the words, “the heavens approve,” while the underneath appears the startling sentence, “a new order of ages.” Adepts are instrumental in inaugurating the American Revolution in this land of the “new race,” and adepts are behind scenes now, setting in motion the forces which will inaugurate “the new order of ages,” which even now is near at hand.[119]

After Judge’s death, Griggs’s name, once again, features in the Branch Activities of the American Section, most frequently as a Theosophical lecturer in Providence, Rhode Island.[120]

In 1897 Willard became involved with Eugene Debs’s (1855-1926) Social Democracy Party, and worked as Debs’s private secretary.[121] He then became secretary to the colonization committee that sought to find land for the socialist colony in the American West that had “been one of Mr. Debs’s pet projects.” At the Social Democracy Convention (Chicago) in 1898 the party was split on the colonization question, and at the conference, and the plan was officially abandoned.

By 1898 the Theosophical Society in America was fractured by infighting. Ayers would join the largest of the splintered groups led by Katherine Tingley, leading was then known as Universal Brotherhood Lodge No. 114.[122] Griggs was not a supporter of the Universal Brotherhood during the “schism” of the American Section in 1898. It was said that “the Tingley trouble made him very sad. He didn’t want to see the ranks split up so.”[123] One of the last public lectures he delivered was titled, “Theosophy, What It Is, And What It Is Not,” which he presented two weeks before his death.[124] Griggs died of Bright’s Disease on May 19, 1899, at Bellevue Hospital, New York.[125] His final moments are remembered by Sadie:

When he was getting unconscious, I asked him if he could see the Madame [Blavatsky] and he gasped “Yes.” That was the last he said to me.

I know he is coming back to the earth; how soon I cannot tell. He died in convulsions, so by that I know he will have a better body. It is my own sincere belief that he will have the body of a woman. That will not make any difference, when I die, I may come back in the body of a man. Of course, in the future life we will be man and wife just the same. That makes me bear my grief calmly. He will be back soon; he told me so, and I believe it. The madame has already come to see me and told me it was alright. She is with me all the time, and he will be soon, too.

It doesn’t make any difference what sort of a body a person comes back in after death. If they have lived as Mr. Griggs lived, they come back in a better body. He believed that, too, and always said that it was nothing to die.[126]

Griggs’s funeral was held on May 22, 1899, at Fresh Pond Crematorium.[127] Almost immediately after his cremation, Tingley’s group gloated over his death, intimating that he “fell dead in the street” because he “forsooth, and did not believe in [Tingley.]”[128]

In 1901 Bridge became a member of the Boston Stock Exchange.[129] He began having “stomach trouble” around this time, an illness which would ultimately result in his death. On December 4, 1904, Bridge died suddenly at his home, 1462 Beacon Street, in Brookline, Massachusetts.[130]

That same year (1901,) Willard and 125 others later purchased three hundred acre tract of land near the west channel of Puget Sound (Washington) where they established the Burley Colony.[131] (This may have been informed by W.Q. Judge, who believed that “Seattle had been built on the site of an ancient and great city,” and that “the Puget Sound neighbourhood would become, in time, one of the most important centres in the United States.”)[132] Willard writes:

I still regarded Socialism the instrument to bring about Universal Brotherhood on the material plane, I was enthusiastic and no movement is successful without enthusiasm. The idea was to colonize the state of Washington, and elect the Senators and Congressmen. I believed in the feasibility of the plan because by having a place somewhere where socialist agitators could be fed, they would not be starved into silence as so many had been.[133]

Willard left after two years, and moved to Point Loma where he worked for the Tingley Theosophical Society until he died in Los Angeles in 1942.[134]

Though records of Baxter’s overt involvement with the Theosophical Society diminishes over time, its influence can be seen in his writings. His 1904 history of the Holy Grail, written as a companion piece for Edwin A. Abbey’s frieze paintings in the Boston Public Library, being one such example.[135]

We find Ayers teaching law at the University of Nebraska in 1905.[136] In 1913 he became Dean of the Law School at the University of Idaho. His tenure there ended in 1917 when the State Board of Education removed him from his position without citing a reason. Many suspected it was because he was “perhaps too outspoken in expressing [his] opinions of men high up in politics of the state.”[137] Ayers subsequently formed a new law firm in Spokane, Washington, in September 1917.[138] He lived the remainder of his years in that city, dying in 1933.[139]

SOURCES:

[1] Hinsley, Curtis M. “Boston Meets the Southwest: The World of Frank Hamilton Cushing and Sylvester Baxter.” In The Southwest in the American Imagination: The Writings of Sylvester Baxter, 1881–1889. (eds.) Hinsley, Curtis M; Wilcox, David R. The University of Arizona Press. Tucson, Arizona. (1996): 3-36.

[2] National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications, 1795-1905; Roll #: 205; Volume #: Roll 205 – 01 Oct 1874-31 Dec 1874. Ancestry.com. U.S., Passport Applications, 1795-1925 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007.

[3] This detail above all seemed to have the most lasting impact, writing in the 1920s Baxter recollects: “He was the first master of Fraternal Lodge when it was reorganized after long inactivity in consequence of the anti-Masonic agitation, and transferred from Barnstable Village across the Cape to Hyannis. He was the first high priest of Orient Chapter of Hyannis. Sylvester Baxter Chapter of West Harwich was named in his honor. He was a prominent member of Boston Encampment (now Commandery) of Knight Templars.” [Hinsley, Curtis M. “Boston Meets the Southwest: The World of Frank Hamilton Cushing and Sylvester Baxter.” In The Southwest in the American Imagination: The Writings of Sylvester Baxter, 1881–1889. (eds.) Hinsley, Curtis M; Wilcox, David R. The University of Arizona Press. Tucson, Arizona. (1996): 3-36.]

[4] Haglund, Karl. Inventing the Charles River. MIT Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. (2002): 120.

[5] Mitchell writes: “Two of my earliest local assignments impressed me with the disadvantage, first of excessive professional zeal, and secondly, of knowing too much. The other cub reporter was Sylvester Baxter, now one of the few remaining veterans of Boston journalism of that date, and well-known subsequently not only as a poet of delicate fancy but also as a pioneer in the movement for a Greater Boston and in the practical development of the splendid park system which grew out of the metropolitan expansion.” [Mitchell, Edward Page. Memoirs Of An Editor: Fifty Years Of American Journalism. Charles Scribner’s Sons. New York, New York (1924): 78.]

[6] Hinsley, Curtis M. “Boston Meets the Southwest: The World of Frank Hamilton Cushing and Sylvester Baxter.” In The Southwest in the American Imagination: The Writings of Sylvester Baxter, 1881–1889. (eds.) Hinsley, Curtis M; Wilcox, David R. The University of Arizona Press. Tucson, Arizona. (1996): 3-36.

[7] Hinsley, Curtis M. “Boston Meets the Southwest: The World of Frank Hamilton Cushing and Sylvester Baxter.” In The Southwest in the American Imagination: The Writings of Sylvester Baxter, 1881–1889. (eds.) Hinsley, Curtis M; Wilcox, David R. The University of Arizona Press. Tucson, Arizona. (1996): 3-36.

[8] Baxter, Sylvester. “Walt Whitman In Boston.” The New England Magazine. Vol. VI, No. 6 (August 1892): 714–721.

[9] Hinsley, Curtis M. “Boston Meets the Southwest: The World of Frank Hamilton Cushing and Sylvester Baxter.” In The Southwest in the American Imagination: The Writings of Sylvester Baxter, 1881–1889. (eds.) Hinsley, Curtis M; Wilcox, David R. The University of Arizona Press. Tucson, Arizona. (1996): 3-36.

[10] H.M. “Isis Unveiled and the Todas.” The Spiritualist. Vol. XII, No. 10 (March 8, 1878): 110-111.

[11] “In very ancient days the sons of God, we are told, visited the daughters of men, and a man could hardly be a hero unless he were a demi-God. It is also alleged of perhaps all the great civilizers and saviors of men, in the old world, that they were born of pure virgins, and we were reminded by Mr. O’Sullivan, in his valuable article of Feb. 22ud, in your journal, that this was the case with Christ, Buddha, Confucius, and Zoroaster. But, perhaps, the most extraordinary coincidence of all is that the same is alleged of Montezuma, the Civilizer of the Aztecs, in America, who taught them to build cities which indeed they did throughout an area from the city of Mexico to San Francisco, Montezuma also taught them to worship the one Great Spirit, symbolized by fire, which was never allowed to be extinguished in their temples. In his case there could have been no prestige of precedent to make it incumbent to prove that his conception was exceptional. Dr. Bell, in his Toot Tracks m North America, thus describes the legend of the birth of Montezuma: ‘Long ago a woman of exquisite beauty ruled over these valleys. Many suitors came from far to woo her, and brought presents innumerable of corn, skins, and cattle. Her virtue and determination to remain unmarried continued alike unshaken; and her store of worldly possessions so greatly increased, that when drought and desolation came upon her land, she fed her people out of her great abundance, and did not miss it, there was so much left. One night, as she lay asleep, her garment was blown from off her breast, and a dewdrop from the Great Spirit fell upon her bosom, entered her blood, and caused her to conceive. In time she bore a son, who was none other than Montezuma.’ One of Montezuma’s great precepts, like that of other great teachers, was, ‘Desire to live at peace with all men.’ The Spaniards, who persecuted the Aztecs, had also heard of the same doctrine.” [Scrutator. “The Birth of Montezuma.” The Spiritualist. Vol. XII, No. 10 (March 8, 1878): 119-120.]

[12] Sotheran, Charles. “Isis Unveiled and the Todas.” The Spiritualist. Vol. XII, No. 14 (April 5, 1878): 161.

[13] “Life In Boston.” The Inter Ocean. (Chicago, Illinois) October 5, 1895.

[14] Baxter, Sylvester. “The Father of the Pueblos.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. Vol. LXV, No. 385. (June 1882): 72-91.

[15] “Coming to Boston With Strange Rites.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) March 1, 1882.

[16] Baxter, July. “An Aboriginal Pilgrimage.” The Century Magazine. Vol. XXIV, No. 3. (July 1882): 526-536.

[17] The New York Times stated: “When the Zuni faith was first revealed to man, one of the conditions imposed upon the patriarchs of the tribe was that they should go to the sea-side every month and bring home a quantity of sea-water for incantation purposes. As the region now known as New Mexico was then near the borders of what is now known as the Atlantic Ocean, this was an easy task. But, as all geographers and other scientific persons very well know, the American continent has been steadily rising from the sea, ever since its foundations were laid. It has been estimated by a well-known scientific person that the continent has risen three-quarters of an inch during the last five centuries without making any allowance of the strata of tomato cans and hoop-skirts formed along that portion of the Atlantic sea-board frequented by Summer visitors. If the student of theology will calculate the time required, on this basis, to raise from under high-water mark that portion of the American continent which lies between the Atlantic Ocean at Boston and the country of the Zunis in New-Mexico, he will ascertain with tolerable accuracy the age of the Zuni faith. And this calculation is now being worked out by several Harvard Professors, who will, in time, give the result to the world, showing that the Zuni variety of paganism is so very aged that the Hindu faiths now being imbibed by Olcott, Blavatsky and the other Theosophists may be considered as modern inventions.” [“A Boston Revival.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) March 31, 1882.]

[18] “A Boston Revival.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) March 31, 1882.

[19] “The Tide Of Immigration.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York) March 17, 1882.

[20] “Atlantis.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York) March 18, 1882.

[21] Baxter, Sylvester. “Walt Whitman In Boston.” The New England Magazine. Vol. VI, No. 6 (August 1892): 714–721.

[22] Hinsley, Curtis M. “Boston Meets the Southwest: The World of Frank Hamilton Cushing and Sylvester Baxter.” In The Southwest in the American Imagination: The Writings of Sylvester Baxter, 1881–1889. (eds.) Hinsley, Curtis M; Wilcox, David R. The University of Arizona Press. Tucson, Arizona. (1996): 3-36.

[23] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3514. (website file: 1B:1885-1890); Sylvester Baxter. [12/17/1885.]

[24] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. I, No. 1 (April 1886): 30-32; Leland, Kurt “Alarums and Excursions: William James and The Theosophical Society.” Theosophical History. Vol. XIX, No. 4 (October 2018): 135-157.

[25] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. I, No. 1 (April 1886): 30-32; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3388. (Website file: 1B:1885-1890) Charles R. Kendall; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3206. (Website file: 1B:1885-1890) Hollis Bowman Page.

[26] Hinsley, Curtis M. “Boston Meets the Southwest: The World of Frank Hamilton Cushing and Sylvester Baxter.” In The Southwest in the American Imagination: The Writings of Sylvester Baxter, 1881–1889. (eds.) Hinsley, Curtis M; Wilcox, David R. The University of Arizona Press. Tucson, Arizona. (1996): 3-36.

[27] “The Pulse of The People.” The Theosophical News. Vol. I, No. 6. (July 27, 1896): 2.

[28] Reno, Conrad. Memoirs Of The Judiciary And The Bar Of New England For The Nineteenth Century: With A History Of The Judicial System Of New England. The Century Memorial Publishing Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1900): 294-296.

[29] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3507. (website file: 1B:1885-1890); George D. Ayers. [12/17/1885.]

[30] “The Pulse of The People.” The Theosophical News. Vol. I, No. 6. (July 27, 1896): 2.

[31] Whitman states: “There’s Sylvester Baxter—he’s a theosophist and says I’m one. I had a letter from London the other day—from a young man there. He says he’s a socialist—then says I’m a socialist, too. Tucker sees anarchism in the Leaves—sees me for an anarchist. So it goes.” [Traubel, Horace. With Walt Whitman in Camden: Vol. II. (July 16, 1888-October 31, 1888.) Mitchell Kennerley. New York, New York. (1915): 37.]

[32] Traubel, Horace. With Walt Whitman in Camden: Vol. I. (March 28-July 14, 1888.) Small, Maynard & Company. Boston, Massachusetts (1906): 119, 122.

[33] “Many will find in Whitman, the fullest measure of mystic truths, plainly and significantly stated, to be met with in any modern poet. For instance, a recognition of the reality of Reincarnation, and of its necessity, constantly recurs in his poems.” [S.B.J. (Sylvester Baxter & William Quan Judge.) “Poetical Occultism: Pt. III.” The Path. Vol. I, No. 9 (December 1886): 270-274.]

[34] “Sylvester Baxter to Walt Whitman, 6 December 1886.” The Walt Whitman Archive. Gen. ed. Matt Cohen, Ed Folsom, and Kenneth M. Price. Accessed 20 December 2023. <http://www.whitmanarchive.org>.

[35] (Birth) [Trahair, Richard C.S. Utopia And Utopians: An Historical Dictionary. Routledge. London, England. (1999): 442-443]; (Death.) [Ancestry.com. California, U.S., Death Index, 1940-1997 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2000.vOriginal data: State of California. California Death Index, 1940-1997. Sacramento, CA, USA: State of California Department of Health Services, Center for Health Statistics.]

[36] Richard C.S. Utopia And Utopians: An Historical Dictionary. Routledge. London, England. (1999): 442-443.]

[37] Willard writes: “The growth of moral ideas is due to improvement in economic conditions. The conditions of their lives have changed. The single class of newspaper writers has become divided differentiated and specialized. The various cogs must work more steadily, brilliancy is sacrificed to effectiveness, and the necessity as well as the opportunity for regular habits among newspaper writers becomes apparent.” [Willard, Cyrus Field. “Reporters’ And Editors’ Unions.” The Inland Printer. Vol. VIII, No. 11 (August 1891): 953-955.]

[38] Smythe, Albert E.S. “The Diary Of Mr. W.Q. Judge.” The Canadian Theosophist. Vol. XIII. (March 15, 1932): 16-17; Willard, Cyrus Field. “Some Old Boston Bones.” The Canadian Theosophist. Vol. XX, No. 10 (December 15, 1939): 301-303.

[39] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 5604. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Cyrus Field Willard. (Boston.) (12/1//89)

[40] LeWarne, Charles Pierce. Utopias on Puget Sound, 1885-1915. University of Washington Press. Seattle, Washington. (1995): 131-132.

[41] On January 3, 1888 William D. O’Connor writes to Whitman: “The article by the wretch named Willard in The American Magazine filled me with indignation. What a beast a man must be who comes to you with a letter of introduction, and goes off to caricature and lampoon you in a magazine!” [“William D. O’Connor to Walt Whitman, 3 January 1888.” The Walt Whitman Archive. Gen. ed. Matt Cohen, Ed Folsom, and Kenneth M. Price. Accessed 17 December 2023. <http://www.whitmanarchive.org>.]

[42] Willard, Cyrus Field. “A Chat With The Good Gray Poet.” The American Magazine. Vol. VII, No. 2 (December 1887): 122-127.

[43] Fogarty, Robert S. “American Communes, 18651914.” Journal of American Studies. Vol. IX, No. 2 (August 1975): 145–162.

[44] Willard, Frances E. “A Visit To Madame Blavatsky.” The Chautauquan. Vol. XI, No. 4. (July 1890): 466-468; LeWarne, Charles Pierce. Utopias on Puget Sound, 1885-1915. University of Washington Press. Seattle, Washington. (1995): 131.

[45] Baxter, Sylvester. The Old New World: An Account of the Explorations of the Hemenway Southwestern Archeological Expedition in 1887-1888, Under the Direction of Frank Hamilton Cushing. The Salem Press. Salem, Massachusetts. (1888): iii.

[46] “Reviews.” Lucifer. Vol. IV, No. 21 (May 15, 1889): 262-263.

[47] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol II., No. 10. (January 1888): 318-319.

[48] “Proper Kind of Magic.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 5, 1890.

[49] “John Ransom Bridge Dead.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 5, 1904.

[50] Psi Upsilon. “Theta Chapter.” General Catalogue Of The Psi Upsilon Fraternity. Volume X. (March 1888): 15-94. [Bridge bio on p. 60.]

[51] “Occult Lore.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) June 17, 1888.

[52] William Quan Judge to John Ransom Bridge. February 18, 1888. Judge, William Quan, and A. L. Conger. Practical Occultism. Theosophical University Press. Pasadena, California. (1951.)

[53] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3927. (website file: 1B:1885-1890); Herbert A. Richardson. [4/5/1887]; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4139. (website file: 1B:1885-1890); J. Ransom Bridge. [9/27/1887]; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4222. (website file: 1B:1885-1890); Edward I. K. Noyes. [11/1/1887]; “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 12. (March 1889): 393-395.

[54] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 15. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885)

Dr. Ammi Brown. [58 Sears Building, Boston, Massachusetts. (12/1/1875)]; M.J.B. “Dr. Ami Brown.” Universal Brotherhood. Vol. XIII, No. 2 (May 1898): 91-93.

[55] “Mr. Stearns Going To Florida.” The Biddeford-Saco Journal. (Biddeford, Maine) March 2, 1887; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4221. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) George M. Stearns. (Boston.) (11/1//87); “Bell Telephone Suit.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) June 14, 1887.

[56] “Sunday Services.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) January 14, 1888.

[57] In a letter from Blavatsky to W.Q. Judge from late-October 1889, she writes: “To begin, except my sincere apology for having gone into the wrong box. It appears it is not you (not directly at any rate) but Griggs who has ruffled Bridge’s feathers. But the question is: has Griggs acted on his own hook, or have you, Councilors, with yourself at the head made the rule that a President in chair or before taking the chair should pledge himself? If so it’s silly, my beloved son. The President of each E. group must first of all pledge all his members in his presence to obey him and make them repeat the pledge & then only pledge himself before them all to the Esoteric Constitution. And there are & will be cases when a member of the E.S. does not like to join a group, wants to remain unknown or apart from others & then if I have confidence in him, I may allow him to remain an unattached member, make this provision, for it is absolutely necessary. Judge, we have too many enemies not to do our level best to keep our good members, & Bridge & Noyes are honest & sincere, both. They may be fanatics & snap their fingers at personalities, but they are true & devoted to Theosophy to death. Now don’t be a mule-headed Irishman & do not kick against your best friends. There is nothing I would not do for you & I will stick for you till death thro’ thick & thin […] Take therefore my advice & do your best to keep him in friendship at whatever cost. Mead sends to you his letter to me & my answer to him. This may mend matters but not unless you help me. I see now that it is Griggs not you. But I have an old tenderness to Griggs & do not want to ruffle his feathers in his turn.” [Gomes, Michael. “The Letters of H.P. Blavatsky to W.Q. Judge: Part IX: Letter Dated July 7, 1889.” Theosophical History. Vol. V, No. 8 (October, 1995): 270-273.]

[58] Bridge, John Ransom. “Helen Petrovna Blavatsky.” The Arena. Vol. XII, No. 2 (April 1895): 177-184.

[59] Gomes, Michael. “The Letters of H.P. Blavatsky to W.Q. Judge: Part IX: Letter Dated July 7, 1889.” Theosophical History. Vol. V, No. 8 (October, 1995): 270-273.

[60] Bridge, John Ransom. “Helen Petrovna Blavatsky.” The Arena. Vol. XII, No. 2 (April 1895): 177-184.

[61] Bellamy, Edward. Looking Backward. Ticknor And Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1888): vi.

[62] Willard, Cyrus Field. “The Nationalist Club Of Boston.” The Nationalist. Vol. I, (1889): 16-20.

[63] Baxter, Sylvester. The Old New World: An Account of the Explorations of the Hemenway Southwestern Archeological Expedition in 1887-1888, Under the Direction of Frank Hamilton Cushing. The Salem Press. Salem, Massachusetts. (1888): iii.

[64] Willard, Cyrus Field. “The Nationalist Club Of Boston.” The Nationalist. Vol. I, (1889): 16-20.

[65] “The Theosophists.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. (St. Louis, Missouri) May 4, 1891; Bacon, Edwin Monroe. Men Of Progress: One Thousand Biographical Sketches and Portraits of Leaders In Business and Professional Life in The Commonwealth Of Massachusetts. New England Magazine. Boston, Massachusetts. (1896): 195.

[66] Webber, Christopher L. “William Dwight Porter Bliss (1856-1926) Priest and Socialist.” Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church. Vol. XXVIII, No. 1 (March 1959): 9, 11-39.

[67] Franklin, John Hope. “Edward Bellamy and the Nationalist Movement.” The New England Quarterly. Vol. XI, No. 4 (December 1938): 739-772.

[68] (President: George D. Ayers. Vice-President: Anne Whitney. Vice-President: William L. Faxon. Secretary: J. Ransom Bridge. Assistant Secretary: Alice Grant. Treasurer: E.I.K. Noyes. Financial Secretary: Ralph Cracknell. Advisory Committee: Charles Bowers, Cyrus F. Willard. Sylvester Baxter. J. Foster Briscoe. Harry W. Robinson. Martha Moore Avery.) [“The Nationalist Club.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) May 9, 1889.]“Mirror Of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. VI, No. 5 (August 1891): 162-168; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 7255. (website file: 1C:1890-1894); Charles Joseph Bellamy. [7/10/1891.] Bowman, Sylvia E. “Bellamy’s Missing Chapter.” The New England Quarterly. Vol. XXXI, No. 1 (March 1958): 47-59.

[69] [Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 6012. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Edward Stanton Huntington. Boston. (6/1/90.)] Huntington writes: “This information given me by my astral visitor, though requiring many words in written expression, was communicated by what may be described as brief flashes of thought, occupying barely more than a moment of time, as measured by bodily sense. The theories of the seven principles presented by this spiritual teacher were not new; and it occurred to me that perhaps this particular dream of a dead man, given through my unknown ghost, was an old superstition retained by those atoms of his brain which had vitality enough to group together in orderly combination.” [Stanton, Edward. Dreams of the Dead. Lee And Shepard Publishers. Boston, Massachusetts. (1892): 27-28.]

[70] Richard C.S. Utopia And Utopians: An Historical Dictionary. Routledge. London, England. (1999): 442-443.]

[71] Sylvanus. “‘Nationalism’ A Sign of the Times.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 12. (March 1889): 376-378.

[72] Bridge, J. Ransom. “Progress Of Nationalism.” Lucifer. Vol. VII, No. (September 15, 1890): 240-243.

[73] Martin, Rose L. Fabian Freeway: High Road To Socialism In The U.S.A. Western Islands. Boston, Massachusetts. (1966): 126-128.

[74] “Fabian Society and Socialist Notes.” Our Corner. Vol. XII. (July 1, 1888): 61-64.

[75] Webber, Christopher L. “William Dwight Porter Bliss (1856-1926) Priest and Socialist.” Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church. Vol. XXVIII, No. 1 (March 1959): 9, 11-39.

[76] Kirk, Rudolf; Kirk, Clara. “Howells and the Church of the Carpenter.” The New England Quarterly. Vol. XXXII, No. 2 (June 1959): 185-206.

[77] Weir, Robert E. Beyond Labor’s Veil: The Culture of the Knights of Labor. The Pennsylvania State Press. University Park, Pennsylvania. (2010): 73 n. 17; Carter, Heath. Union Made: Working People and the Rise of Social Christianity in Chicago. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (2015): 106.

[78] The National Archives in Washington D.C.; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29; Series Number: M653; Residence Date: 1860; Home in 1860: Mansfield, Tolland, Connecticut; Roll: M653_80; Page: 705; Family History Library Film: 803080.

[79] Ancestry.com. U.S., High School Student Lists, 1821-1923 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2012. Original data: School Student Lists. Worcester, Massachusetts: American Antiquarian Society.

[80] “Proper Kind of Magic.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 5, 1890; “The Madame Called Him.” The St. Louis Post-Dispatch. (St. Louis, Missouri) May 21, 1899.

[81] “City Notes.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island) October 31, 1896.

[82] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry [none.] (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Arthur Griggs Wilmington. It is unclear why Griggs’s surname appears as Wilmington in the registry. His name appears among the bulk of “loose” names under the heading “1878.” in the beginning of Book 1. Blavatsky writes in her diary for December 15, 1878: “Whole day packing up. Dinner. Paris, Wimb., Tom, Marbles and Gustam. Evening. Two Judges—Wm. and John.—The latter initiated. Wilder,—Dr. Weisse, Shin and Ferris, Two brothers Langham, Clough,—Curtis. Griggs came from Connect. to be initiated. O’Sullivan and Johnston of the phonograph. All sent speeches to the Brothers in India. Mrs. Wells, Mrs. Ames and daughter, Maynard, O’Donovan and a painter who came with Mrs. Ames. Edison was represented by E. H. Johnson.” [Blavatsky, Helena P. Collected Writings Volume I (1874-1878.) Theosophical Publishing House. Wheaton, Illinois. (1966): 430.]

[83] “Obituary.” The Sun. (New York, New York) May 21, 1899.

[84] C.T. “Providence (R.I.) T.S.” The Theosophical News. Vol. I No. 19. (October 26, 1896): 4; “Obituary.” The Sun. (New York, New York) May 21, 1899.

[85] “Notes.” The Hartford Courant. (Hartford, Connecticut) May 24, 1899.

[86] “A Golden Anniversary.” The Brooklyn Times Union. (Brooklyn, New York) October 19, 1887.

[87] “Eli And His G.N.K.R.” The Evening World. (New York, New York) February 1, 1889.

[88] “Eli And His G.N.K.R.” The Evening World. (New York, New York) February 1, 1889.

[89] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. IV, No. 9 (December 1889): 290-294.

[90] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. V, No. 10 (January 1891): 325-327.

[91] The Theosophical Movement 1875-1925. E.P. Dutton & Company. New York, New York. (1925): 211.

[92] Gomes, Michael. “The Letters of H.P. Blavatsky to W.Q. Judge: Part IX: Letter Dated July 7, 1889.” Theosophical History. Vol. V, No. 8 (October, 1995): 270-273.

[93] Smythe, Albert E.S. “The Diary Of Mr. W.Q. Judge.” The Canadian Theosophist. Vol. XIII. (March 15, 1932): 16-17.

[94] “Don’t Be Hypnotized.” The Inter Ocean. (Chicago, Illinois) July 17, 1890.

[95] “Talks On Hypnotism.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) July 4, 1890; “Proper Kind of Magic.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 5, 1890.

[96] “Talks On Hypnotism.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) July 4, 1890; “Proper Kind of Magic.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 5, 1890.

[97] Bacon, Edwin Monroe. Boston Illustrated. Houghton, Mifflin, and Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1886): 92.

[98] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4350. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Robert Crosbie. (Boston.) (2/26//88); Willard, Cyrus Field. “Some Old Boston Bones.” The Canadian Theosophist. Vol. XX, No. 10 (December 15, 1939): 301-303.

[99] [Eklund, Dara (Compiler.) Echoes Of The Orient: Vol. I. Theosophical University Press. Pasadena, California. xxxv-xxxvi.]

[100] “Marriages.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) May 9, 1891.

[101] “The Madame Called Him.” The St. Louis Post-Dispatch. (St. Louis, Missouri) May 21, 1899.

[102] Willard, Cyrus Field. “Some Old Boston Bones.” The Canadian Theosophist. Vol. XX, No. 10 (December 15, 1939): 301-303.

[103] Haglund, Karl. Inventing the Charles River. MIT Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. (2002): 120.

[104] “Life In Boston.” The Inter Ocean. (Chicago, Illinois) October 5, 1895.

[105] Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, U.S., Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original data: Town and City Clerks of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Vital and Town Records. Provo, UT: Holbrook Research Institute (Jay and Delene Holbrook.)

[106] Bridge writes: “[I] would like to know why it would not be a good scheme for a few men—say the house of Rothschilds—who own $100,000,000 or $200,000,000 of gold-bearing obligations, gradually to corner the available supply of gold; then, by calling loans and other well-known methods at their command, create a general panic, force prices down as far as they dare, buy in as many of the depreciated securities as they can handle, wait for a return of confidence and then repeat the operation until they literally own the earth or as much of it as may fill the measure of their desire? What is to prevent?” [Bridge, J. Ransom. “If Confidence Were Gone.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) August 31, 1893.]

[107] Harvard College: Report Of The Secretary No. V. June, 1899. Evening Post Job Printing House. New York, New York. (1899): 16.

[108] Higgins, Shawn “Archival Material: A Letter From George D. Ayers to William James.” Theosophical History. Vol. XIX No. 4. (October, 2018):132-133; James, William. “Person and Personality.” entry in Johnson’s Universal Cyclopedia. A.A. Johnson Company. New York, New York. (1895): 538-540.

[109] “Vivekananda At Greenacre.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) July 28, 1894; Phelps, Myron H. “Green Acre.” The Word. Vol. I, No. 2 (November, 1904): 52-67.

[110] Willard, Cyrus Field. “Some Old Boston Bones.” The Canadian Theosophist. Vol. XX, No. 10 (December 15, 1939): 301-303.

[111] “Theosophy.” The Daily Item. (Lynn, Massachusetts) October 1, 1895; “Mirror Of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. X, No. 7 (October 1895): 225-232; “Mirror Of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. X, No. 8 (November 1895): 260-264.

[112] “Mirror Of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. X, No. 7 (October 1895): 225-232; “Mirror Of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. X, No. 8 (November 1895): 260-264.

[113] “Mirror Of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. X, No. 6 (September 1895): 194-200; “Not To Turn World Upside Down.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) November 18, 1895; “Theosophists Providing Free Sunday Night Suppers.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) November 4, 1895.

[114] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 10,633. (website file: 1D: 1894-1897) James F. Morton, Jr. [34 Hancock Street, Boston, Massachusetts. Boston T.S. (2/1/1894.)]

[115] “Around The Labor World.” The Boston Post. (Boston, Massachusetts) January 10, 1897.

[116] R.A.C. “Of Boston Origin.” The Theosophical News. Vol. I, No. 3. (July 6, 1896): 3.

[117] [Leoline credited with “Brotherhood Supper”: “Wed With Mystic Rites.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) May 4, 1896]; [Bliss: “Authority On Near East Dies.” The Churchman. Vol. CXXXIV, No. 17 (October 23, 1926): 25.]

[118] Bacon, Edwin Monroe (ed.) Men of Progress: One Thousand Biographical Sketches and Portraits of Leaders in Business and Professional Life in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. New England Magazine. Boston, Massachusetts. (1896): 195; Reno, Conrad. Memoirs Of The Judiciary And The Bar Of New England For The Nineteenth Century: With A History Of The Judicial System Of New England. The Century Memorial Publishing Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1900): 294-296.

[119] Ayers, George D. “Christ’s Second Coming.” The Boston Daily Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) June 7, 1896.

[120] “City Notes.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island) October 31, 1896.

[121] Cuppy, Hazlitt Alva (ed.) Our Own Times: A Continuous History of the Twentieth Century: Vol. I. J.A. Hill & Company. New York, New York. (1904): 357; Richard C.S. Utopia And Utopians: An Historical Dictionary. Routledge. London, England. (1999): 442-443.

[122] Reno, Conrad. Memoirs Of The Judiciary And The Bar Of New England For The Nineteenth Century: With A History Of The Judicial System Of New England. The Century Memorial Publishing Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1900): 294-296.

[123] “The Madame Called Him.” The St. Louis Post-Dispatch. (St. Louis, Missouri) May 21, 1899.

[124] “A New Theosophy Society.” The Chillicothe Gazette. (Chillicothe, Ohio) April 29, 1899.

[125] “The Madame Called Him.” The St. Louis Post-Dispatch. (St. Louis, Missouri) May 21, 1899.

[126] “The Madame Called Him.” The St. Louis Post-Dispatch. (St. Louis, Missouri) May 21, 1899.

[127] “Obituary.” The Sun. (New York, New York) May 21, 1899.

[128] “Inside Facts Concerning The Dream City Of Esotero.” The San Francisco Call And Post. (San Francisco, California) August 5, 1900.

[129] “John Ransom Bridge Dead.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 5, 1904.

[130] “John Ransom Bridge.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 6, 1904.

[131] “All Share In The Profits.” The St. Louis Post Dispatch. (St. Louis, Missouri) March 28. 1901.

[132] Hargrove, Ernest Temple. “Letters From W.Q. Judge.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXIX, No. 1 (July 1931): 35-45.

[133] Fogarty, Robert S. “American Communes, 18651914.” Journal of American Studies. Vol. IX, No. 2 (August 1975): 145–162.

[134] Cuppy, Hazlitt Alva (ed.) Our Own Times: A Continuous History of the Twentieth Century: Vol. I. J.A. Hill & Company. New York, New York. (1904): 357; Richard C.S. Utopia And Utopians: An Historical Dictionary. Routledge. London, England. (1999): 442-443.

[135] Baxter, Sylvester. The Legend Of The Holy Grail As Set Forth In The Frieze Painted By Edwin A. Abbey For The Boston Public Library. Curtis & Cameron. Boston, Massachusetts. (1904.)

[136] “Plans For Two New Building.” The Lincoln Star. (Lincoln, Nebraska) June 14, 1905.

[137] “Shattuck’s Removal Surprise.” The Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington) May 22, 1917.

[138] “Form New Law Firm.” The Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington) September 4, 1917.

[139] Washington State Archives; Olympia, Washington; Washington Death Index, 1940-2017. Ancestry.com. Washington, U.S., Death Records, 1907-2017 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2002.