“Hau,” said Goose, in the Siouan custom. He shook hands with General George Armstrong Custer, and sat down.

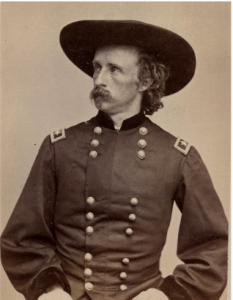

Custer looked every inch a soldier, except that he wore his hair in long curls. He was a young man still, very tall, and erect, and typically carried himself well.[1] Typically. Custer meekly faced Goose. It was a week before their departure on the Black Hill Expedition. Goose, one of the Ree guides engaged in the expedition, had entered Custer’s office in Fort Lincoln with important information. Custer, though greatly annoyed by the frequent requests of the native scouts, invited Goose to come in. Perhaps Goose’s horse was injured, and he wanted to exchange him for another steed; maybe Goose’s rations didn’t suit his tastes; perhaps he wanted some yellow stripes on his pantaloons, or three stripes on his arm like his fellow guide, Bloody Knife, or Bear’s Ears. Custer was surprised to discover that Goose had not come with complaints, but rather revelations. Goose had come to make an important disclosure; a secret which had never been known to the white man.

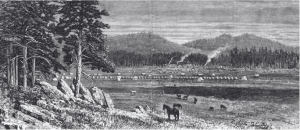

Fort Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory.

“What is it, Goose,” asked Custer, “what can I do for you?”

With weighted gutturals (smoothed over by an interpreter,) Goose pantomimed a story.

“Far out toward the setting sun, several days’ journey from the Missouri River, is a great hole in the ground where the white man has never been,” said Goose. “It is a hole with a great wide mouth in the side of a big hill. Before this great hole I had once camped with some of my tribe, and had gone inside it, but I never found the end of it, nor had any member of my tribe. The entrance to this cave is larger than the side of this room. I had gone into a distance as far as from the General’s house to the Missouri River. I was afraid to go any further. It was very dark, and I had no light. There were some places in the cave where a man had to crawl on his hands and knees to get through. If you brush your coat or blanket against the side, it will be covered all over with a yellow powder. There is no water in this cave, but there is a strange smell, which frightened us, and we turned back. The entrance is near Slim Butte, which we will pass on the way to the Black Hills. It will be very little, if any, out of the way.”

“Yellow powder you say?”

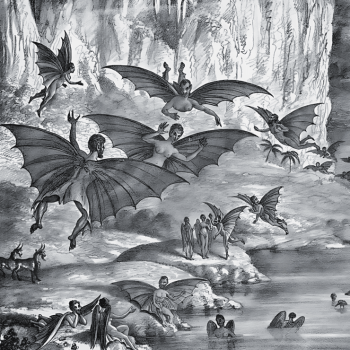

“In this cave lives an old man, with a long, white beard, who is without ‘beginning of days or end of years.’[2] It is the abode of the evil spirits being continually filled with the shrieks and wailings of the tormented damned. [3] On the wall are great inscriptions in an unknown language, in letters as long as my arm, which even the medicine men of my tribe have been unable to interpret, and to which have also come the wise men of all tribes, but with no better success. Sometimes these figures shine as if they have been rubbed with fire, and then the shrieks and groans are the loudest, the echoes reaching even to the open air. These inscriptions, my people believe, are the edicts of Manitou, the Great Spirit, against those in torment, and they shine like fire whenever they are renewed.”

“Are these pictures cut into the rock or simply painted?” Custer asked, pointing to a paper hanging on the wall.

“Carved.”[4]

General George Armstrong Custer.

~

The Black Hills (where the cave was located) enclosed the earthly paradise of the Sioux who, naturally, “guarded it with the utmost jealousy.” All the U.S. Government knew of it was “positively is very little, and that little very vague.” At certain seasons (coinciding with the times of their religious celebrations) the Sioux went there to hunt. The Black Hills were holy ground “of the very holiest sort,” the antechamber of Manitou, where the annual Sundance (the most solemn of festivities) was held. “According to the evidence of Sitting Bull, the Indians had wont in former days to make their hunting there a mere accessory to—very possibly a part of—their worship. They hunted, but not for want of wantonness; but, if it were not a profane comparison, partook of the pleasure of the chase as sort of sylvan sacrament.” There was an immemorial prohibition among the Sioux which outlawed permanent encampment of a band within the limits of the Black Hills, and this ruling had always been enforced. But the Natives had seen—especially during the previous decade—the disappearance of the bison owing to the white man. The tribes to the south had, for the past two years, been stirred to the edge of revolt by the white man’s whole-sale slaughter of the buffalo along the railroad lines. A similar peril menaces was promised in the north; hence the preservation of the Black Hills was considered absolutely necessary if they hoped to live and hunt.[5]

This, of course, conflicted with the aims of the U.S. Government, which, in the aftermath of the American Civil War (1861-1865,) had shifted its focus to westward expansion. Thousands of white settlers made the trek to the American interior—the home of 250,000 Indigenous People from dozens of tribes in the Great Plains between the Rocky Mountains and Mississippi River. It was not simply settlers from the eastern states, it was global in scope. The town of Bismarck, founded in the Dakota Territory one year earlier (1873,) was a prime example. The Northern Pacific Railway named the town Bismarck in honor of the German Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, hoping to attract German immigrant settlers.[6] In 1874 the U.S. Government sent General Custer into the Black Hills to find a suitable location for a new military fort—as well as report on the area’s natural resources, especially gold. The expedition was in direct violation of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie in which the U.S. government promised to respect the autonomy of the Great Sioux Reservation—an area designated for the Lakota Sioux.

Explorers of the U.S. Government had skirted the periphery of the Black Hills, and had tried, but failed, once before to penetrate the interior of the region. The first attempt was made by Lieutenant Gouverneur K. Warren (of the United States Topographical Engineers) who conducted an army reconnaissance of the Black Hills in 1857. The small party lead by Warrens left Fort Laramie and scouted the western edge of the Hills before the Lakota Sioux compelled him to turn hack at Inyan Kara mountain. Then, in 1859, William F. Raynolds explored and mapped the Belle Fourche River (to the north and east of the Black Hills) en route to Montana and Wyoming. If successful, Custer’s Expedition would mark the first successful mapping and exploration of the area by the U.S. Government.[7]

The personnel of Custer’s Expedition consisted of ten companies of the Seventh Cavalry, one each of the Twentieth and Seventeenth Infantry, a detachment of Ree and Sioux scouts (together with the necessary guides, interpreters, and teamsters,) about one thousand men in all. The wagon train consisted of one hundred wagons and ambulances, while the artillery consisted of three Gatlings and a 3-inch rifle.[8]

Colonel William Ludlow.

Colonel William Ludlow was chosen as the Chief Engineer of the Expedition. For surveying purposes, Ludlow had a detachment of six engineer-soldiers was employed. The two sergeants, Becker, and Wilson (each with one man as an assistant) would keep separate trails with prismatic compass and odometer. Wilson’s vehicle would be an ambulance. Becker, a solemn, old, spectacled sergeant, of the Engineer Corp, rode in the awkward, two-wheeled vehicle, the “go-devil,” specifically constructed for surveying.[9] Becker was one of the many Germans in the army. They were said to make excellent soldiers, and were “generally well-educated men,” who enlisted immediately after their immigration, “for the lack of something else to do.” (The Irish, so it was claimed, made better cavalrymen, for they were “more bold and reckless,” but for a “good reliable infantryman, or ‘dough-boys,’ as the trooper’s call[ed] them, the Germans [were] the best.”)[10]

A team of scientists (or “Bug Hunters” as the soldiers referred to them) under Ludlow’s supervision would carefully survey the topography of the country and finally provide an accurate map of the Black Hills.[11] Professor Horace Newton Winchell, who taught courses in geology, botany, and zoology at the University of Minnesota, would produce a geological map of the terrain; George Bird Grinnell, a paleontologist from Yale, and representative of Othniel C. Marsh, would classify and categorize any new species of bones encountered.[12]

Lastly, Ludlow hired W.H. Illingworth, a photographer in Saint Paul, to furnish stereoscopic views of the scenery.[13]

~

The last contingent of the Expedition was a small group of newspaper correspondents. They were William E. Curtis, a journalist reporting for The Chicago Inter-Ocean and The New York World; Samuel J. Barrows, a correspondent for The New York Tribune; Nathan H. Knappen, representing The Bismarck Tribune; Aris Donaldson, botanist and correspondent of The Saint Paul Daily Pioneer, and Fred W. Power, of The Saint Paul Daily Press.

Aris B. Donaldson.[14]

Aris Donaldson, alone of the titled scientists, was known exclusively known as the “Professor.”[15] (He had resigned his position as professor of English literature at the University of Minnesota to join the expedition.)[16] The Professor was a portly man, who wore a straw hat, a comfortable coat and vest, and a large canvas patch on the baggy part of his pantaloons. When choosing a horse from Quartermaster Dandy, the Professor chose “Dobbin,” a long, lank beast with very deliberate movements. Dobbin was very docile, but that suited the Professor’s taste.[17] When the Professor road off on him, he explained that he did “slowly and carefully, so as not to jar the sensitiveness of his rheumatic back.”[18]

The Quartermaster’s people considered him a singular curiosity in human nature.

“The Professor is very learned,” said Curtis, “his great stomach must be the storehouse of his memory, and it is full of dictionary words, for nowhere else in himself has he the room to stow away the great sentences that always roll from his mouth, like mountains of lava from a crater.”[19]

William E. Curtis.[20]

“Under that old slouch hat,” an officer told Curtis, pointing to an old mule driver, “I think you will find a romance.”

“Not a very inviting field to search in,” Curtis replied.

“But you haven’t seen the face yet—when you see the face, you will be more reasonable—see there!”

Curtis took a closer look at the man as he removed a gray slouch hat, to wipe the sweat from the beach of his ocean of hair.

“That’s Buckskin Joe,” continued the officer. “He’s the oldest man on these plains, I believe, and one of the most singular fellas I ever saw. He has had a very interesting life, and you had better interview him. His wife ran away and married a Congressman some years ago—but touch lightly on that, as the old fellow is very sensitive.”[21]

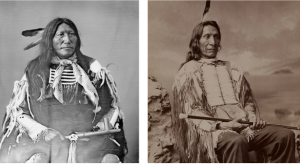

Curtis went to the Native section of the camp, and found Custer’s favorite scout, Bloody Knife, gesticulating wildly, and talking in an angry tone to a group of warriors. Just as Curtis approached, Bloody Knife called attention to the stripes on his arm, Notwithstanding his tyranny, Bloody Knife assumed to be the protector of his band and was very careful to see that they were not imposed upon. Bloody Knife was the offspring of a matrimonial alliance between a Sioux chief and a Ree woman, and although the two nations were ancestral enemies, he seemed to wield considerable influence over both peoples. He was once chief of the Hunkpapa tribe of Sioux, brazen with their enmity toward the whites, but having been deposed by his people for some unknown reason, he took refuge among his old enemies. After the band of scouts was organized, Custer appointed made Bloody Knife a sergeant, and he was as proud of his stripes as a militiaman was of his epaulets. His authority among his warriors was that of a dictator, but he took the burden of annoyance off Lieutenant Wallace’s shoulders,

Curtis had the opportunity, now, to learn more about the scouts before the Expedition proper. The story of Bear’s Ear’s was particularly interesting.

The Rees, like many other tribes of Native Americans—were divided into various bands. Disputes amongst members of these bands were not uncommon. Bear’s Ears was no exception to the rule. He had a rival—some say over the heart of a woman—who took a piece of wood from a firepit and struck him. Bear’s Ears did not retaliate. His fury was intense, but careful and steady. If Bear’s Ears had the support of the community, he would have simply taken the top-knot from his enemy’s head and not the scalp. But he was not supported. He waited to see if his antagonist would make amends by sending him a horse—a peace-offering to the insulted Rees. But no horse came. Bear’s Ears made a silent vow of retribution. He supplicated before the gods. Every day for nine months he rose at dawn and traveled three miles from the village to make penance and give offerings to his favorite deity. He did not pray that he might love his enemy. He prayed that he might hate him more. In his gruesome determination, he sliced off two of his fingers and yielded them to the Great Spirit—Manitou—as a sacrifice.

The following Winter his tribe went on a Buffalo hunt. Bear’s Ears and his rival were both in the hunting party. They were a long way from the village. The main party decided to camp, but Bear’s Ears was determined to return home. Unknown to him, his enemy had the same intention. He was traveling a narrow trail when he heard the voice of his enemy shouting to him to get out of the way. It added insult to Bear’s Ears well-steeped injury; he turned aside as the object of his hatred ventured to pass by. Bear’s Ears raised his gun and shot him dead. He cut out the dead man’s heart. He mounted the vacant saddle and rode to his village. He told his mother to pack up what she wanted, while he prepared a vengeful meal. He filleted his enemy’s heart; broiled it; ate it. He craved this meal for many days. He hungered for this sacrament of atonement. The two fingers he gave to Manitou were a modest sacrifice for the recompense they secured. Before daylight, he was a fugitive en route to the Sioux camp. He was welcomed as a friend and ally. For seven years was an adversary in his own home. In his exile Bear’s Ears learned the secrets which coursed through the stony veins of the Black Hills.[22]

Among the Ree there was a mysterious-looking individual clothed in a woman’s frock but wore a warrior’s scalp braid and accoutrements. He was the “drudge” of the Ree, performing all the cooking, bringing all the wood and water, and looking after as many ponies as his other duties would allow. The Ree warriors looked upon him with an unmistakable air of superiority. This character was also prevented from participating in war dances or other pastimes with the men.

“What is his story?” Curtis asked Bloody Knife.

“The form of a man but the heart of a woman,” replied Bloody Knife. “He had not the courage to endure the tortures a young man must subject himself to before he can become one of the warriors. So, he has to live with the women and do a woman’s work.”

“Why does he come with you?” Curtis asked.

“He wants to get rid of that frock,” said Bloody Knife. “If he takes a scalp, it comes off him.”[23]

His frock might come off sooner than later. Shortly before leaving on the Expedition, news reached Fort Lincoln that the Sioux attacked a Ree village near Fort Berthold, and a battle ensued. The son of Bloody Knife, and a brother of Bear’s Eye were killed, along with several other Ree warriors accompanying Custer. As a result, the surviving warriors were anxious for revenge. [24]

~

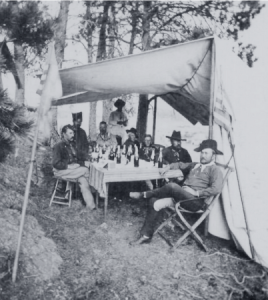

Seventh Cavalry.

On the morning of July 2, 1874, a half a dozen bugle-calls transformed the Seventh Cavalry into a well-guarded, orderly caravan. Every soldier, teamster, horse, mule, and wagon made up a link in a long chain. The whole line moved across the dusty plain. Custer led the march, mounted on his favorite steed, Dandy. He wore a buck-skin hunting suit which, though lacking subtlety, demonstrated a sartorial courage as yet unseen in the West. The man in a blue shirt and straw hat next to Custer was Fred Grant, the President’s son. Ludlow, showing no evident fear of the unforgiving sun (which mummified the alkali-soil of the Bad Lands,) was hatless by their side.

The veritable “plague of locusts,” sweeping the American West in the summer of 1874 made itself known in the first days of the march. “The wings reflecting the light make them appear like tufts of cotton floating lazily with the wind,” Ludlow would say. “In descending through the slanting rays of the sun, they resemble a fall of huge snow-flakes.” [25]

~

Goose’s story of the cave was, by now, circulating throughout camp—gaining enthusiastic embellishments over each retelling. The entrance of the cave was now considerably larger, with new passages and chambers.

“I hear there is a small back window in the cave that allows gleams of daylight to reward the explorers.”

“Caves don’t have window’s you fool!”

The discovery of Troy, announced just months before the expedition, added another layer of excitement.[26] The men of the Seventh Cavalry were confident that they were on the brink of a great discovery. The Sioux medicine men could not interpret the inscriptions, but that did not mean that no one could.

“Goose can’t read Schliemann, Layard or Wilkinson,” said the men, “he can’t interpret the characters.”[27]

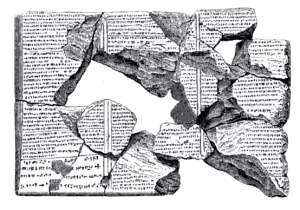

The “Deluge Tablet.”[28]

“It is clearly evident that these inscriptions are cuneiform, just like the ‘deluge tablet’ that George Smith just found.”

In 1872 Smith discovered a cuneiform tablet which he referred to as the “Deluge Tablet,” because the story, once translated, seemed to be another version of the Biblical Flood narrative. What he had actually unearthed was what would become known as The Epic of Gilgamesh.[29]

“I still think they’re hieroglyphs, to which the genius of Champollion has furnished us a key.”

Some in the camp preferred the “Phoenician theory” and referenced the characters to the era of King Hiram himself. This conclusion, of course, was disputed by the “Hebraists,” who saw in the writing compelling evidence that the “lost tribes of Israel had settled in North America.”

From Goose’s description, it was certain that one of the letters was an ‘Aleph’ in the Paleo-Hebraic script.

“Maybe ol’ Joe Smith and them Mormons are right?”

“Oh, shuddup.”

“Say,” said one man, “what are they doing over there?”

Custer’s men looked at the Ree scouts in their segment of the camp. They were horrified by the “nakedness” of the painted Ree, who were whirling around the crackling gloom of dim firelight. They were invoking some divine blessing in a vaporous, rhythmic ritual. Their moaning music was of minor keys; soft tones which crescendoed into howling winter wind in leafless sylvan limbs. Striking their drums with determined emphasis, the men arose, one by one, and united through dance, leaped on alternating legs. They crouched, weaved, plunged, and swayed. Then knives, tomahawks, and pistols were brandished high in the air while. Each movement appended by the scattered beats of the song. The ritual ended with thin subdued cries. Pipes were lit (and re-lit.) Every Ree took a puff or two and relinquished it to the next man.

Smolhalla and his priests.[30]

“It’s that prophet of theirs,” said one man. “He’s been unrelentingly preaching a crusade of extermination against the whites.”

“That half-blood?” said another man.

“I heard he was a white man,” said another, “a Mormon.”

“Why would a white man preach for the extermination of the white man? And what is it with you and Mormons?”

For the past year or so, talks of a mysterious messianic Native had been the subject of widespread curiosity. The most mischievous (and persistent) of the stories told about this prophet, claimed that he preached a bloody campaign against the whites.[31] Smohalla, a name which the soldiers did not know, was revered as a direct messenger from the “Other World.” Some say that Smohalla began to receive his divine visions after witnessing Mormons “receiving commands directly from heaven.” Others said these visions began while mourning the loss of a beloved child.[32] Whatever the case may be, he was believed to be an omniscient sage who could speak every language and possessed a book “containing mysterious characters […] which [Smolhalla] said were records of events and prophecies.”[33] Smohalla’s movement (known, variously, as the Waashat Religion, the Prophet Dance,) had spread amongst the tribes of the Plains, and many now believed that their fallen warriors, mourning the degeneracy of their sons, had returned to the land of the living, riding “coursers [horses] of fire.” “The spirits of the dead are on a war-path,” said the Ree guides.[34] The tributaries of this tradition (along with elements of the Spiritualist-Shaker tradition) would influence the soon-to-come “Ghost Dance” religion of the Plains.[35]

~

Away from the enlisted men, in the officer’s tent, as was often the case when old comrades gathered together over food and drink, wounds were compared, stories were swapped, and jokes were shared. July 3, 1874, marked the eleventh anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg; a battle in which a twenty-three-year-old Custer, leading the Union Army’s 1st Michigan Cavalry, drove back a pivotal Confederate attack. The “Boy General” became a media-darling (a celebrity which Custer actively cultivated.) It was the General’s custom (when not in buck-skins) to don a gold-laced, black-velvet uniform, spurred-boots, a red scarf around his neck, complete with a wide-brimmed sombrero over his long, blonde, hair (which he perfumed with cinnamon oil.)

There were over fifty-thousand casualties during the battle of Gettysburg. It would be difficult to find humor in that campaign. There was, however, at least one story; a story which related to Ludlow’s cousin-in-law, General Winfield Scott Hancock.

“Remember Joe Parker,” said Ludlow.

“Those boys only saw the absurdity in everything, no matter how serious,” one of the officers replied.

“Well, it was during the heat of battle on Cemetery Hill. General Hancock was severely wounded, so he sent Parker off to find General Abner Doubleday—who was the senior division commander—and notify him that he was now in command of the Second Corp. Parker found Doubleday sitting under a large tree. ‘General Doubleday,’ says Parker, ‘General Hancock has been seriously wounded, and you will—’ Before Parker had time to finish the sentence, a shell burst directly over the Doubleday. The shock stunned him, and he stumbled over. ‘Oh, I am killed!’ old Doubleday said, ‘I am killed!’ Well now, Parker couldn’t resist the opportunity for a joke.”

“Of course, he couldn’t.”

Abner Doubleday.

“Parker rode off in search of General Gibbon,” continued Ludlow. “‘Hancock has been wounded, and Doubleday has been killed,’ Parker tells Gibbons. ‘You are to takeover command of the corp.’ Word spread quickly that Doubleday was dead—hell, Parker told Hancock himself that Doubleday was dead. Hours later a railroad train with Hancock, his staff, and a handful of wounded officers was moving toward Baltimore. Hancock laid suffering intensely on a stretcher, but his mind and sympathy were with his officers and the boys who were dead and wounded. ‘It’s too bad about Doubleday’s death,’ said one wounded officer sitting near him. ‘Doubleday ain’t dead,’ replied another officer. ‘I seen him in command of the corp. after you was wounded—it weren’t two hours before I left the field.’ Hancock was confused. ‘Why, Joe Parker told me that he was killed.’ Parker, who was in the front car joking with the boys, was promptly summoned. ‘Captain Parker,’ says Hancock, ‘didn’t you tell me that General Doubleday was killed?’ ‘Certainly, I did,’ replied Parker. ‘He told me he was, and what the devil else was I to do but to take his word for it?’”[36]

Custer, laughing, then told a story from his West Point days with Colonel Ludlow (the antics of which prevented Custer from receiving a diploma with the rest of the graduating class of 1861.)

“Why you see,” said Custer very rapidly (gesturing over a tureen of stew,) “I began my tour at the usual hour in the morning. Ludlow was a greeny, but he had pluck. One evening, when I was officer of the day, some upperclassman pitched on him, and he showed fight. The boys encouraged them until they got into a good square out-and-outer, just as I was going my rounds. Instead of sending both of them, as I should have, to the guard house, you know, I pushed back some fellows who were trying to trip Ludlow and said that there must be fair play. It was a good one, and Ludlow was getting the best of it when the boys began to interfere again. I was getting my hand in again, when old Lieutenant Hazen, Instructor in Artillery, came around, and instead of arresting Ludlow and the other fellow, he locked me up for allowing the fight to go on, and I was in the guard house when my class graduated. But they wanted soldiers at Washington just then, and they sent me on. I never went back to West Point again.”[37]

Ludlow graduated eighth in his class at West Point in 1864 and would serve as Chief Engineer of the Army of Georgia under General William Tecumseh Sherman. For his bravery, Ludlow was promoted to rank of Colonel before the war was over.[38]

Officer’s Table.[39]

~

The company marched along a creek that was a tributary of the North Fork of the Cannon Ball River. The land, since they last made camp, was undulating. Ludlow, Goose, Barrows, the Professor, and Curtis were a clot in the equestrian stream.

“I was ruminating the other morning,” said the Professor, “on the extraordinary good fortune which secured me the use of so excellent an animal. I have only one exception to make among his entire category of characteristics, and that is: ‘Dobbin’ is not very foot-sure. Sometimes when we are passing over a territory at all imperfect in its surface—he stumbles—and it does seem as if he would displace my lumbar vertebrae or give me a hebdomadal rupture.”[40]

Curtis let out a mirthful laugh. The strange Professor was beginning to grow on him. Seeing the Professor come in from a long day’s march, with a benevolent smile beaming on his sun-burned, half-peeled face, with a huge nosegay of flowers in his hand, made Curtis genuinely happy.[41] The Professor’s imagination was very fertile, and he frequently entertained his companions with the remarkable experiences which he and Dobbin encountered.[42] The soldiers, who now knew the jolly pedagogue’s kind heart, and his “hearty enjoyment of everything,” was becoming a favorite everywhere. Notwithstanding his pedantry, he seemed like a “great child, enjoying a summer’s holiday.”[43]

In the distance a small exposure of sandstone rock, in a low mound, could be seen.

“Dog Teeth Buttes,” said Goose.[44]

Buttes.

There was a man, well-remembered, by the Natives of these parts, and the scattering of crosses on Lakota graves bore testament to that fact. He was the man who first called the hills of the Badlands, “buttes,” the word for “mound” in his native French. Father Pierre-Jean De Smet was a Belgian, Catholic priest, and Jesuit missionary. Nailing a large, black crucifix to the dashboard of his covered wagon, Father de Smet traversed the Badlands, from tribe to tribe, befriending the native peoples with his uncommon grace. He was known as the “Friend of Sitting Bull,” and as such, convinced the Sioux war chief to enter negotiations with the American government during the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. Father De Smet, as the one story went, once promised a certain Sioux chief the gift of a pistol—the use of which De Smet had a difficult time explaining. Procuring a gun from a nearby French trading post, he returned to the home of the chief, and keeping his word, presented the weapon. De Smet, however, did not give any bullets. Undeterred, the chief took a brief excursion, returned with a handful metal—which he planned on melting into bullets. De Smet, realizing that the metal was gold, warned the Sioux never to announce the existence of gold in their land. “The pale faces’ would undergo untold hardships to possess it,” he told them.[45]

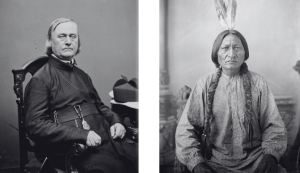

(Left) Pierre-Jean De Smet. (Right) Sitting Bull.

Word leaked out, and rumors that the Black Hills were a real-life “El Dorado.” In 1866 General William Tecumseh Sherman, fresh from his scorched-earth campaign against the Confederate States, turned his attention West—towards the land of the Sioux. Sherman was met resistance—notably from a prophet-chief named Crazy Horse. (When Sherman received the hacked-up remains of 80 white troops who were garrisoned at one of the many illegal forts in the Black Hills—he got the message.) In 1867 Sherman met with Sioux leaders to broker a peace. The result was the Laramie Treaty, which stipulated the removal of military forts in the Black Hills, and the promise not to return.

When De Smet died, the Sioux broke the cross on his wagon into little pieces and distributed the fragments as a relic of a holy man. They were far more impressed by this priest who embodied the teachings of Christ than they were with the totem of the church. The relics were a reminder—that the only good white man they had encountered—was “now with the Great Spirit.”[46]

“There are three types of people in this world,” said Ludlow, winking at Barrows, “Men, women, and clergy.”[47]

Samuel J. Barrows.[48]

“Not a praying man, Colonel?”

Barrows, a Unitarian minister, took it on the chin. In 1871 he enrolled as one of the 23 students at Harvard Divinity School for training, but it was an uncertain period for the institution which had seen a decline in growth (and funding) since 1840. Future Harvard Divinity School Dean, Frances G. Peabody, who was in the same academic cohort with Barrows, looked back on his education during this time as “a disheartening experience of uninspiring study and retarded thought.”[49] To pay for his schooling, Barrows worked as the personal secretary of the influential Harvard biologist, Louis Agassiz. To secure more money, in 1873, Barrows agreed to act as special correspondent for The New York Tribune, accompanying Custer’s Yellowstone survey. That’s how he first came to know the General.[50]

“It is no use talking to me about prayer,” said Ludlow. “I know that it works.”

Even as a little boy, Ludlow knew its ability. He was an active child, and thoroughly enjoyed the outdoor life. Growing up on the coastal hamlet of Islip, Long Island, offered him an abundance of nature—he was particularly fond of maritime activities. (It was a bitter disappointment when he could not follow his elder brother, Nicoll Ludlow, into the U.S. Navy.)[51]

“I will never forget the time when my brother and I were playing in the snow,” said Ludlow. “My mother would knit mittens for us to wear every winter, and every year I would lose them. On one of those cold days, I went out to ice-skate with Nicoll. As we left the house, my mother reminded me of all the care she took in knitting my gloves—and asked me not to lose my gloves yet again. When the time came for us to return home, I remembered my mother’s appeal, but the mittens were missing! We searched for them everywhere. The ground was white with snow. The mittens were red. They should have been easily spotted. There wasn’t a trace of them anywhere. I was upset beyond measure. How could I possibly face my mother after what she had said!? I fell to my knees in the middle of the road and prayed—Nicoll, too—that we might find those mittens—a broken-hearted prayer. We rose from our knees and looked around. There, just feet away from us, lying on the snow, were the mittens.”[52]

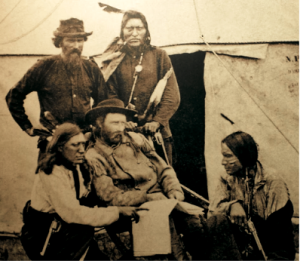

Custer (seated) with (left to right) Bloody Knife, Pvt. John Burkman, Goose, and Little Sioux.

That evening General Reynolds’ map of the country was spread before Goose, who looked at it curiously, but with indifference, until he was told what it was.

“Here,” said Custer, “is Heart River,” indicating with his toothpick along its course, “and here is Fort Lincoln and the Missouri.”

Goose looked at the map silently for a few moments, then seized it, and turned it around until he had got the points of compass to agree.

“Ugh,” said Goose, “this is not right.”

A pencil was handed to Goose, who traced the course of several branches of the Cannon Ball River. He paused with his pencil on Slim Butte, which he placed at least fifty miles from where it stood on the map. Custer showed him where the mountain was indicated. Goose looked at it a moment, and threw the map aside, with a sneering “UGH!’’

“Perhaps it is not,” said Custer. “This map was made before anybody ever went there, and the men didn’t know anything about it except what the Indians told them.”

“The Indians were white Indians, I guess,” said Goose. “You can make another map when you go there with me.”

“Yes, that is what we are going for,” Custer replied. “I will give you a map if you would like one.”

“My map is here,” said Goose, pointing to his head with a haughty gesture. After a few moments of silent meditation, he asked Custer for an order on the sutler for a drink of whisky.[53]

~

The following day the cavalry marched seventeen miles west through a prairie in a land that was “the finest yet seen.” At night they camped near a creek named, according to Goose, “Where the bear stays in winter.”[54]

They marched until sunset, and while Curtis was lying around waiting for dinner, he saw Buckskin Joe sitting by a fire he had just kindled near his wagon. He was on the ground, knees against his chest with his arms around them, staring at the flames. With his long bushy white hair and beard that covered the whole of his face, he looked something like the poet, Longfellow.

Buckskin Joe’s attention was drawn to Curtis’s approach by the crackling of the dry branches under his foot.

“Good evening.”

“Will you let me light my pipe from your fire?” asked Curtis.

“Certainly,” he said, half-unconsciously stripping a little twig, and putting it into the flame.

Curtis took the taper from his hand, and in exchange offered his tobacco pouch (a courtesy that is always extended on the frontier when two people meet.)

“No, thank you,” he said, shaking his head. “I seldom use it.”

“I hope you don’t object to the odor, for I wanted to sit by your fire and smoke till my supper was ready.”

“Not at all,” Buckskin Joe replied, with a wave of the hand, “make yourself as comfortable as possible.” He stood up and renewed the wood, then took a camp kettle and hung it on the tripod.

“They tell me you’re the oldest man on these plains—have you ever been down this way before?”

“In ‘55,’” he said quietly, “I went out with Harney, and our trail was fifty miles south of this—we went around the foot of the Black Hills and up the Cheyenne.”

In answering other questions put forth by Curtis, Buckskin Joe told him politely (and briefly) that for forty-one years he had been between the Northern Mississippi and the Rocky Mountains. His language was “pure, grammatical, and well-pronounced,” and his voice was soft, almost musical.

“You don’t know how it is, my friend,” Buckskin Joe continued, “the open air and a team of mules is as much to my taste as your city home to you. I couldn’t breathe in a city. I have been on the plains forty-one years, and now and then I have vowed that I would quit it, but before my team was unharnessed, I’d be anxious to get off again.”

“But you’re getting pretty old for this business.”

“Yes, I’m old—sixty-four last January—but I am tougher now than most of the young fellas. I don’t suppose I shall hold out much longer, though, and I’m going back to the State’s once more before I die this fall, if I have good luck. I ain’t been in the States since ‘59, and I’ve got some friends I ain’t heard from for nine years now, and maybe it wouldn’t do much good to go down yonder—but I’d like to see how things look. There were only three bridges over the Schuylkill when I was there last, and now they tell me there’s one at most every street.”

“Were you from Philadelphia?” asked Curtis.

“Yes. I ran away from my home in Philadelphia when I was nine-years-old, and went into the Western part of the State, and worked for nigh seven years, then I went back home and worked under the very same roof with my mother, she tending dairy and I doing chores, and she didn’t know me all that time. I stayed there a year or two, and then I came West, and hereabouts I’ve been at Sioux City, Fort Dodge, and all around—teaming and trading with the Indians ever since, and I couldn’t leave it now.”

“But it seems queer to me,” Curtis suggested, “that a man can live so long in such a way without a wife and family.”

“I have no family, but I was married once. I lost my wife some years ago.” Buckskin Joe rubbed his eyes. “Smoke and alkali dust,” he said, as he got up and moved around restlessly, taking the kettle off the hooks, and lifting the lid. Buckskin Joe had trenched his memory deeper than he pleased.[55]

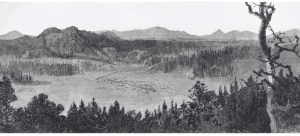

“Index Butte” Hidden-Wood Creek (Reached July 8, 1874)[56]

~

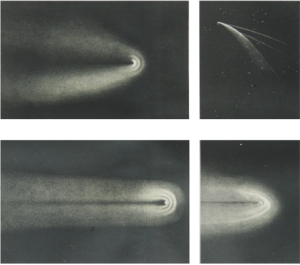

On July 10, the Bear’s Ear’s stared at the “nebulous streak upon the northern skies” with Curtis and Barrows. They were looking at Coggia Comet, which they had seen near the Big Dipper, very plainly, for three consecutive nights.

“It may exercise a potent influence,” said Bear’s Ear’s. “Whether it be malign, I cannot say. It may be pressed into the service by Smolhalla and be exhibited as proof of the wrath of Manitou with the pale faces.[57]

Coggia Comet.

“Tell us more about this cave,” Curtis said to Bear’s Ear’s.

“Somewhere near the center, there is a great nest,” said Bear’s Ears. “It is like the nest of the eagle; this is the nest of thunder. This spot even my people do not visit.”

The heart of the Black Hills, it was said, held the springs of immortality. Native legends held that the rocky arteries of mystical caves circulated from the heart of the central hill. A gauntlet of supernatural obstacles and temptations surrounded it—making its entrance all but impossible to discover. Magic deer, Bear’s Ears explained, wooed the hunter, like Sirens, to turn aside, but those who, for even a single moment, diverted from their path, were instantly torn to shreds by the panthers who barred the unworthy from profaning her secrets. Those who completed the first part of the quest, next faced a subterranean pathway with its own set of perils. If successful, the reward at the center of the cave was the sacred Wapka—the Living River—a cascade of holy water that coursed through the gloomy bowels of the earth and vanished in the darkness. This water offered an extension of life, matching the lifespan of long centuries the great eagles in their eyrie on the summit of the hill had accrued.

“An early chief, to whom all later chiefs looked to as an exemplar, sought this Living Water—and succeeded,” said Bear’s Ears. “This upset the balance of things.”

When the chief repeated the trial, a century later, to renew his extended lease of life, the Great Spirit was compelled to intervene. When the chief was in the bowels of the cave, the mountain itself swallowed him alive. He was never seen again. The Living Water vanished. The great eagles disappeared, leaving only the thunder as a sentinel to guard their nest. But the Great Spirit was not cruel. A compensatory spring appeared, pouring from the hill, and those who bathed in it were offered the gift of invulnerability. The pilgrim who sought this gift, had to travel blind to the spring, drink its waters, and bathe in it completely, for, like the story of Achilles, wherever the water did not touch, that spot remained a source of vulnerability. The Sioux claimed that their most successful warriors were those who bathed in this spring and testified to her miraculous properties (attributing their frequent and inexplicable evasion of bullet and blade.) The most invulnerable of these warriors kept on the lee side of his horse (the side where the wind blew,) a container of this water during a battle.[58]

But there were also a mysterious people, at least according to Bear’s Ears, who seemed to reside within the cave.

“The people in those caves you cannot kill,” said Bear’s Ears. “They can stand close to a gun that the powder burns them, yet the ball will not hurt them.”

“Shall we meet these Indians?” asked Barrows.

“Yes,” said Bear’s Ears. “They love that land. Why should they not fight for it?”[59]

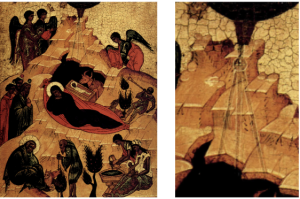

Across cultures, around the globe, caves represented a passage between the worlds of the living and the dead—a “petra umbilicalis” that tethered humanity to the primordial “womb and tomb” of mother earth. The Aztecs traced their origin to Seven Caves (an event echoed in the creation stories of the Pueblo, and Hopi.) Hellenic poets (and their successors) interpreted the “Gate of Hades” as a cave of descent, of “death, return, initiation, and rebirth.” Psychologically, entering a cave offered an opportunity for introspection, incubation, and recalibrating to the source. Alternatively, a cave explorer (psychologically or otherwise) runs the risk of disorientation in the depths—or claustrophobia (self-doubt.) Alchemically (or allegorically) caves are a location of transformation and the culmination of a spiritual quest.

Christ in tomb-shaped crib inside a cave.[60] (Picture on right with close-up of the star.)

Such ideas were not relegated to the esoteric—on the exoteric side the importance of caves can be found in both Islamic and Christian traditions. It was in a cave of Hira that the Prophet Muhammad heard the reverberating voice of God.[61] The Christian Theologian, Origen of Alexander wrote in 248 AD: “In Bethlehem, the cave is pointed out where [Christ] was born, and the manger in the cave where [Christ] was wrapped in swaddling clothes. And the rumor is in those places, and among foreigners of the Faith, that indeed Jesus was born in this cave who is worshiped and reverenced by the Christians.”[62] (Orthodox Christian icons portray Christ’s birth in a cave. The Christmas Star/comet above the cave illuminates the aperture of the cave revealing the Christos preserved within the earth womb.)[63]

As for the “trials and tribulations” the Sioux warriors were said to face when approaching the “Living Water,” well that had echoes in the Christian world, too, in the legend of the Holy Grail. The word “Grail” itself came from the French graal and medieval Latin, gradale, meaning “in stages” (the name of the serving dishes in which meals were brought to the table—in stages.) In medieval Grail Romances, the knight heroes went on a mystical quest (fraught with dangers and temptations) for the chalice that once held the blood of Christ (“Living Water.”)[64]

~

The line of march left camp on the Grand River, pursuing a westerly course parallel with the river where they ultimately encountered a large basin bound to the north and west by high sandstone bluffs. The men were weary from the hot and monotonous trek but were comforted with the knowledge that they would soon reach the cave.

On July 11, at 4 o’clock in the afternoon, the party reached a spot where Custer thought it best to leave the main command. From there he proceeded with a small detachment in search of the cave.

So much had been spoken of its spectacle and mysteries by the guides. Fervent anticipation stirred within the soldiers and rumors passed from saddle to saddle on the likely result of their exploration.

“I know it is here,” Goose insisted. His confused expression suggested otherwise.

A sobering doubt crept into the minds of many of the men.

“There ain’t no cave at all!” they thought.

“You gonna tell your tribe how you pulled one over on the white man, Goose?”

“Whaddya say boys? ‘Roast Goose’ for supper tonight?”

Goose, Bloody Knife, and some other scouts hastened about the rocks on their ponies. Finally, Goose came to a standstill. With indifferent affectation, the guide made a gesture with his hand. “Come,” he said, spurring his pony.

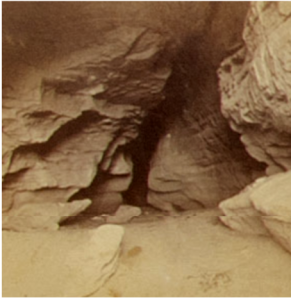

Custer drove his horse up the canyon till he stood in a narrow gully. His men followed suit. When they reached the aperture of yawning sandstone the guides scattered fiercely among the ravines. The men of the Seventh Cavalry sprang from their saddles and ran towards the cave, eager claim that first climax of discovery in the legendary grotto where unrighteous souls were imprisoned.

Goose remained outside while some of the younger scouts accompanied Custer’s men. His melancholy was evident. He had already performed a great sacrilege by leading the white man to the cave—even if he did not personally assist in its profanation. “Young men now,” Goose grunted, “are not like their fathers.”[65]

Entrance to Ludlow Cave.

As they approached the cave, they were astonished to find a woman standing over a flat rock taking the hair off a deer hide with a scraper. When the soldiers approached her, she ran into the cave. When they went in after her, she could not be found. “Well,” said one of the men, “she must be hiding far in.”[66]

Custer, who sent word back to camp that the cave had been found, greeted Ludlow and the scientific crew when they arrived.[67]

Petroglyph On Canyon Wall Near Ludlow Cave.[68]

A closer examination of the cave art commenced. The walls were covered with painted designs, and on the ceiling, a flash of lightning was depicted.[69] Toward the interior there were cryptic engravings carved high on the wall with a deep “accomplished precision which rivaled European master-sculptors.” Near the engravings, “about as high up on the wall as a man could reach,” there were impressions of a human foot, four inches long, and two hands (of similar style and relief) an inch deep into the wall.[70] One of these hands was positioned in such a way as to suggest that it was traced from a living model—but if this were true, it meant this person, whoever it was, must have been a towering eight-foot-tall figure. Other hieroglyphs—equally unique—mesmerized the treasure hunters.[71] Two sides of the large entrance walls formed were covered with pictures of men, horses, birds, snakes, buffalo, and embellished with “curious and original, if not aboriginal designs.”[72]

Goose stood at the entrance for a few moments, silently looked at the symbols, then turned away, never approaching the cave again.

The men soon discovered, in the crevices between the rocks at the entrance, bows and arrows, beads, bracelets, rings, and other relics. Custer himself seized an old flint-lock pistol as long as his arm—others in the party found an old knife, a shaving brush, and a peculiar gold ring with the inscription “A.E.” [73] Very strange for a cave supposedly unmolested by the white man. After sifting through the sand, one soldier unearthed a peculiar. The macabre memento was passed around the company, with quips and jibes from some, solemn questions and theories from others, inquisitive silence from most. Three holes perforated the forehead just above the left eye, presumably from bullets; it was evident to the company that the previous occupant of that ghostly subterranean tenement had been the victim of savage cruelty—apparently, some captive brought from the frontier and made a sacrifice to the spirits of the cave. It was said that the cave itself was a “prophet.”[74] If so, what did this mean?

Skull.

The commandant of the left wing of the expedition, Colonel Joseph Tilford, began carving away at the exterior wall of the cave. He was a genial man, very popular in and out of his regiment (and well-known in Chicago) but he could not resist engraving his initials.[75]

Joseph Tilford.

Ludlow, meanwhile, was conducting a thorough survey inside. Among those who accompanied him were Barrows, Thomas “Mac” McDougall, and Benjamin “Benny” Hodgson.

“Is this the cave!” said Mac.

“Yes,” said Benny, who had accompanied the advance earlier that day.

“Well, I’ll be damned.”

The men entered the long narrow corridor, Mac lifted his lantern and Benny followed, Barrows third, followed by a crowded battalion of spirited, curious soldiers who wished to see this “old man with a long beard.” The passage was only wide enough for a single file. Mac pressed on. The corridor gradually narrowed, and Mac’s caliber was too cumbersome. There was the fear that he would stick in the breach. The whole column backed out, and Benny, a smaller man, advanced to the front. The pressure renewed. Benny got down on his hands and knees. They continued 200 feet into the bowels of the earth until finally, Benny found that he must “ram it out” if he were to go any further.

“Ram him home, boys!” Cunningham yelled.

(Left) Benjamin “Benny” Hodgson. (Right) Thomas “Mac” McDougall.

The boys rammed and rammed, but the rock would not budge. A report was sent back to the rear column that the lieutenant was desperately stuck at the other end.

“Send for a corkscrew, a corkscrew,” was the cry.

The knot of men was eventually untied.[76]

Ludlow ultimately followed the narrow passage some four hundred feet until it became so small, he could proceed no further.[77] When he emerged from the cave, he told Custer his impression of the site.

“The sandstone ledges around the cave are systematically positioned with their connection to each other,” said Ludlow. “This suggests to me the possibility of artificial construction.”

Custer looked doubtful.

“There is too much good engineering shown in their arrangement to have been the work of nature,” Ludlow insisted. “The exterior presents the appearance of a scarp, and suggests strongly the ruins of an old, fortified city fairly laid out with bastions and curtains, with sally-ports guarded by towers.[78] I am prepared to risk my professional reputation on the fact that this is no freak of exuberant nature, but a deliberate work of defense.”[79]

General Custer and Libbie Custer in their home at Fort Lincoln.

Custer christened the grotto “Ludlow Cave,” in honor of his old friend.[80] Though he claimed to be unaffected by the supernatural legends surrounding the cave, Custer wrote a letter to his wife, Libbie, a few days later in which he confessed his bewilderment of the depictions in the cave. “I think this was all the work of Indians at an early day,” Custer writes, “although I cannot satisfactorily account for the drawings of ships found there.”[81] Curtis agreed with Custer. In his dispatch to The New York World, he wrote:

The work is clearly not that of any tribes of Indians now known here. The figures are very rude—as rude as any designed by Cheyenne, Sioux, or Mandan, but the depths of incision, the greater boldness of the occasional curves, and the compactness of the whole work do not favor the hypothesis that any of these tribes wrought the work. Nor could the early mound-builders have been the authors since no sign whatever of their occupancy of this part of the country has yet been afforded. Rudely hazarding an opinion one would say from the selected situation and quality of work, that its authors were of far Eastern origin, but if this were the case why should it occur at a point so far inland! If Custer’s expedition, not having any particularly lofty aim, were to throw some light on the vexed question of our Indian tribes, that would be a notable instance of stumbling on an unexpected conclusion. As yet, however, the scientists are inclined to consider volcanoes and their thermal or mineral springs are real bases of superstitions concerning all these mystic caverns and hills of which we have heard so much natural phenomena improved to their own advantage by wily medicine men and chiefs.[82]

~

The next place was Black Butte. Here Custer sent two scouts, Bull Neck, and Skunk Head, back with mail. The plentiful timber of the country was so black, that it resembled a “prairie that had been burned.” They followed a river, shallow like the Little Missouri, and hemmed on both sides of the bank with pine timber. The Dakotas called it “Beautiful River,” but it was known among the white explorers as “Big River.” Across the river was Cut Butte, with two high points, and it was there where they made camp; the scouts on a hill, and the soldiers were in the valley.[83]

The soldiers were on high alert, “Mac,” who was on the flank, discovered a small party of about twenty Natives watching their movements.[84]

They were three miles distant from the “hostile Sioux,” and Ludlow shot a buffalo while hunting. It was only wounded in its flank, however, and galloped off directly toward the Sioux camp. Ludlow followed (but dared not fire again.) After some time, the buffalo began to drag its hind quarters, and he fought it for several hours. He eventually bested it with his knife.[85]

The “Bug Hunters,” in their vigilance, were also on high alert. Grinnell, the geologist of Yale College, discovered an important fossil, a bone about four-feet long and twelve inches in diameter. It was presumed that it once belonged “to an animal larger than an elephant.”[86]

Steadily they marched, through the Prospect Valley, and Belle Fourche, inching toward the Black Hills.[87] They made a long march to find grazing, so as to approach the clay desert fresh the next morning. The day was warm and sultry. The whole command were exhausted and disheartened. But sleep did not come that night. At sunset the sky was illuminated in the west with a strange crimson glow, that resembled the “shadow of a burning world.” The rhythm of the air had ceased to beat. Many sensed that a great wrong was brooding. Tired and sleepy, the men quickly pitched their tents, gulped their dinner down, and stretched their weary limbs on their blankets. Around midnight everyone was awakened by the swaying and flapping of their tent. Tremendous clouds of dust drifted under the curtains with every gust. The whole sky was covered with heavy black clouds, broken at times by vivid flashes of lightning. The sound of thunder which echoed among the hills, was exceedingly grand.[88] The air was dry and heavy, and the wind came in sudden spasms with a velocity that ripped the tent pins from the earth as if they were leaves. The men swore savage oaths, in defiance of the elements, yet the blinding streaks of lightning called their bluff of courage. The frail tenements of their souls desperately clung to the ropes of the tent, to wind around their bodies, now anchors, heaved upon the ground.[89]

~

The Expedition entered the Black Hills on July 20, but two deaths dampened the excitement.[90] Before daylight on July 21, John Cunningham, of Company H died of Diarrhea, “superinduced by physical exhaustion.” [91] The next day, while camped in the Redwater Valley, a fight broke out. [92]

Joseph Turner and William Roller, old comrades who served together for nearly five years, revisited a long-standing feud. This was the preface of an impromptu duel (both had murder on their minds.)

One of them asked Custer for permission to finish the fight.

“I don’t care,” said Custer.

Roller drew first.

“Hold on, hold on!” said Turner.

A shot was heard. Then another.

Turner was shot the arm and again in the chest.[93]

“He got the best of me,” gurgled Turner, “or I should have settled him.”[94] He was placed in an ambulance but died just as they entered camp in the evening.[95]

Both of the deceased belonged to Colonel Tilford’s division, so the responsibility of preparing the funerals fell to him. Sergeant O’Toole, an Irish-Catholic of H Troop, was selected to read the service. O’Toole, however, had no prayer-book.

“It is just like my wife, I know, to put one in my satchel, although I haven’t come across it yet.” Colonel Tilford said told O’Toole, looking through his belongings for his copy of the Book of Common Prayer. Tilford, of course, soon found it. “Mrs. Tilford would not have forgotten to pack the prayer book, even if it meant leaving out my shirts!” he told O’Toole, giving him the prayer book.

O’Toole soon returned to Tilfords tent.

“Be jazes, Colonel, I can’t find it.”

“Can’t find what?”

“Can’t find the prayers, sir”

“Can’t find the prayers?” Tilford said in astonishment. “Can’t find the prayers?”

“By God, Colonel, there’s not a damned one of them in the book.”

Colonel Tilford took the book and looked it over. Sure, enough, it was some kind of edition in which the section with the burial service was omitted. It was getting late, and Tilford was puzzled.

“O’Toole—go to Colonel Hale and see if he hasn’t got one.” He quickly returned—pinching the prayer book like one would pinch a rattlesnake in the neck. “I’ve got in now, damn me, Colonel,” said O’Toole, “I was afraid I’d have to repate it from memory.” and O’Toole started off to overtake the procession.”

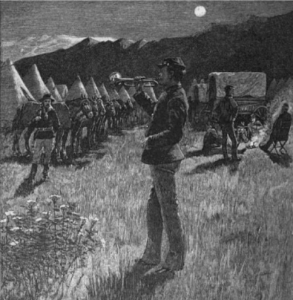

The funeral was held at sunset, (so the attention of any scouting Sioux might not be aroused.) It was cold that night, and the pale light of the moon added an eeriness to the awful significance of the ceremony. The bodies of Cunningham and Turner were folded in their blankets, wrapped in their tents, and sewn fast. The bier was a canvas litter; the hearse an ambulance; the bearers a squad of troopers; and the escort the whole command (the only thing missing were mourners.) The band led the procession from headquarters to the singular grave, a deep hole on the hillside, under a clump of cedar trees. The bodies were silently lowered down by lantern light.

A Trumpeter in Moonlight.

“I am the resurrection and the life,” O’Toole said, slowly, with a heavy brogue, and crossing himself in the Catholic fashion. It sounded strangely beautiful in the quietude that hovered around the lonesome grave. When the service was read a volley was fired over the grave, and the trumpeter sounded “taps,” the “good-night” call of the soldier. [96] A large fire was built over the grave to obliterate all signs of the burial, as the Sioux were known to have opened newly made graves for the purposes of securing a scalp.[97]

Both Cunningham and Turner were desperate characters and were probably serving under assumed names—a common thing in the army. Before he died Turner ordered his back pay and some effects to be sent to a man named Hughes in Jeffersonville, Indiana, and that, most likely, was his true name. The majority of the enlisted men in the army were “simply human driftwood,” men who had committed a crime somewhere, and hid from the authorities by serving in the army under assumed names. Men who could not “brook the liberties and familiarities of society” and took refuge in military discipline. These men, disappointed, disheartened, and ambitionless, found the life of a soldier a relief. Cunningham was intelligent, well-educated, popular, and influential, but lack of opportunity made his soul rich soil for a harvest of indifference. He was aimless, a “foot-ball of fate,” until he was finally kicked into an unmarked grave in the Dakota wilderness.[98]

~

“Good morning, Professor,” said Curtis.

“Good morning, sir,” said the Professor. “How is Mr. Curtis this morning? You look as bright as a dollar.”

“Inwardly so, Professor, if not outwardly, thank you. How do you feel yourself?

“A little fatigued from my long ride yesterday, but still qualified, I think, to meet all the requirements of the occasion. I was pondering this morning upon various subjects, and my train of thought was led into a channel which has become quite familiar to my meditations recently—that of thankfulness, or of congratulation, I may be allowed to say—that I was permitted to accompany this reconnaissance. I have been recompensed triple fold, yea more, for all the hardship and exposure that had attended it.”

“Then your back is better—those lumbar vertebrae were not dislocated after all?

“Dislocated is an erroneous term in that connection, Mr. Curtis, if you will pardon my correction. Physiologically speaking, a dislocation of the lumbar vertebrae would be fatal, but if you refer to the complaints I have previously made, I am thankful to be able to say that my system is in excellent condition once more, and I think I am improving physically rather than otherwise under this vigorous campaign life.”

“Thank you, Professor!” said Curtis.

Half suppressed smiles passed over the faces of the men as they rode through the last valley of the Black Hills.[99]

“The stream disappears, in the mouth of a mammoth serpent,” said the Professor, “twenty-seven feet from ‘ear to ear,’ which drinks all the water, gulping it down when its mouth is filled, three swallows a day. It will compensate you, Mr. Curtis, to ascend the pinnacle of yonder elevation, and obtain an observation of the reptile.”[100] The men were in Inyan Kara, and the Professor learned of the tale connected with the stream from Sioux Scouts. The source of the stream, it was said, was in a beautiful cave “said to contain all of the luxuries of life, natural & artificial.”[101]

They soon entered the beautifully verdant oasis aptly named, Floral Valley.[102] Everybody, even Buckskin Joe, were enraptured with the flowers, and everybody made bouquets. “I would give a hundred dollars just to have my wife see the floral richness for even one hour,” said one officer. The other men chimed in agreement.[103]

Traces of Indians began to be seen. The men of the Seventh Cavalry found several places showing signs of recent encampments. The trail grew more fresh the further they went. The Ree scouts, anxious for revenge, unbraided their hair, rubbed vermilion on their faces, and wrapped white cloths around their head, putting feathers in for a crest (all this in the saddle, as they marched along.) They hummed a war-song in dreary monotone for further seasoning.

Custer caught Bloody Knife’s eye, and gave him a nod, which the old chief understood. Bloody Knife calmly rode to the front of the column. Soon a thin, semi-transparent, smoke was seen rising just over a mile in front of the column. The scouts, tense with impatience, rushed off after their chief. They rode like wildfire until they reached the brow of the hill, where they stopped for a moment, cocked their guns, and crept cautiously, single file, around the side of the knoll.

The scouts were only gone a few moments, when Young Hawk, a handsome youth of eighteen, came rushing back.

“We have found a village of five lodges, a large herd of ponies,” said Young Hawk. “We wait for orders.”

Custer dashed off, with two troops of horsemen (and the remainder of the scouts,) and found Bloody Knife with his party in the hollow of a hill, less than a mile away from the village. The Ree were restrained from an immediate onslaught on the village with great difficulty.

“Have not the Sioux often attacked us and cruelly killed many of our kinsmen? Have they not, just before the Expedition left Fort Lincoln, made a descent on the Ree village at Berthold and slain several of our brethren and made our hearts heavy?”

“Do not dare to fire a shot unless the Sioux attack you,” Custer sternly warned.

Goose, Bear’s Ears, and Louis Agard (the interpreter,) were sent ahead with a flag of truce to enter the village.

The winyan (women) sat in their tipis, while the wakanjeja (children) played around the door. The wicasa (men) had gone up in the woods to hunt. These unsuspecting women and children were greatly surprised to see Custer’s men and were naturally extremely frightened at the band of twenty-five Ree approaching in the distance dressed in war paint and looking “murderously cruel.” The children fled to the bushes. The women were frozen with fright. Agard’s words did little to reassure them. The camp was deserted by all the warriors except one, a tall, slim man, with sharp features, and piercing gray eyes. The warrior bravely came forward and introduced himself as Slow Bull.

“Here comes the White Chief him-self,” said Agard, pointing up the valley. “The one in the blue shirt galloping at the head of the gray horses—he will protect you.”

Fearful that the Ree might not be able to control themselves, Custer

came down the valley at a “rattling pace.”

Custer, first off, his horse, extended arm of friendship to Slow Bull. “Hau.”

Louis Agard with wife.[104]

Slow Bull timidly approached Custer to shake hands. “Hau.”

The made the women breathe freer. Soon the children began to peep out of the bushes, and then timidly come forward and investigate the newcomers.

Slow Bull nodded. He then filled a pipe and passed it around outside the tipi, in which the pipe of peace was lit and smoked. Each member of the circle took a whiff and exhaled the smoke through his nose—if they could (with killikinick tobacco it is not a very agreeable experiment.)

“We have not come to fight,” said Custer, “but to make peace with you, and ask you about the country.”

Slow Bull explained that his people were mostly Hunkpapa, from the Red Cloud Agency. He and his family had never been in this part of the Black Hills before, and he could not tell them the name of the stream they were on and did not think it had any name. His people did not know that Custer was in the Black Hills and had not even heard that they were coming.

“I do not think there are many Indians in the mountains,” said Slow Bull. “We sent runners to the Red Cloud Agency a few days before to learn the news, but they have not returned yet.”

Assured of their peaceful intentions, Slow Bull called in the women and children, and sent some of the older children were sent to fetch One Stab, the chief of the band, and three other men who were in the woods hunting deer.

Slow Bull invited Custer’s party to be seated in his tipi, while he went out to watch for the other men of his tribe. They learned that Slow Bull’s wife, Libbie Slow Bear, was a daughter of the famous Lakota leader, Red Cloud.[105] She was very frightened when Custer first appeared, but she had now recovered, and was so happy that her children and husband were not going to be killed, that she became very agreeable, and entertained Custer’s men in a lively manner. Libbie was evidently a fashionable (though domestic) woman. She had an eye for the kitchen as well as the parlor. One of the first things she told Custer, after the ice was broken, spoke to that effect.

“I do not have a bit of coffee and sugar in the house,” she said, “and my little children have been crying for some days.”

“I promise you,” said Custer, “that we shall remedy this.”

Libbie chatted more freely after that.

One Stab soon arrived, wearing a bruised felt hat, a breech-clout, and a dyed cotton agency shirt. With him were Long Arm, Slim Bear, and Young Wolf. They were quite surprised to find a couple of hundred horsemen in their camp, nevertheless, One Stab invited Custer and his men into his lodge. They again smoked the pipe of peace. It was soon discovered that One Stab’s wife was a daughter of the famous Lakota leader, Red Cloud.

(Left) Slow Bull c. 1872. (Right) Red Cloud.

“The Great Father at Washington has sent me into the Black Hills to find out what sort of a country it is, and whether the Sioux had a good reservation,” said Custer. “We have come down on a friendly visit to look at this country. When we get through, which will be in a few days, we are going back home. We do not want to make war on anybody, and we do not want anybody to make war on us.”

“I am One Stab, Chief of a band of eighty lodges. My people are of the Brule tribe of Sioux, from the Red Cloud agency. We have been hunting in the Black Hills for five months. There are twelve men and women and fifteen children in my village. The rest of my band are scattered in different portions of the Hills, and some have gone back to the agency. I have twenty-seven people with me, but only five warriors. We have killed a great many deer and are going back tomorrow to receive our annuity.”

“Do you want to go along with us for a few days?” asked Custer. “We are making short marches, not longer than you make with your lodges. If you will go with us until we get out of the Black Hills, I will give rations every day to all of the party. If they cannot all go, perhaps some of the men can go.”

The Ree warriors were not pleased with the result of the conference. Bear’s Ear’s was especially animated with signs of hostility, but Custer ordered him under guard.

“I assure you,” said Custer, “none of your party will be harmed.”

“We have only five Indians here,” said One Stab, “but if you want me to send one of my young men today, I can do it. I can show you the way clear up this creek here—then you can go yourselves. I do not want to have any trouble with the white man. I have always been with the white man—I never stayed with the hostiles.”

“I have seen a great many Indians,” said Custer, “but I have never seen any that have been with the hostiles.”

“My friends say that when I meet any Indians that steal any horses from the whites, I always take them away and bring them back to the whites,” said One Stab. “When I meet a big chief like you, I always tell him the best I can. My children are all much scared today because the Rees came—they would not have been afraid of the whites.”

“Could you not stay over in camp for two or three days?” asked Custer.

One Stab at first hesitated, but his wife said, “Yes, we can stay over a couple of nights as well.” One Stab assented.

It was then arranged that the male Indians should come to camp that afternoon and get some rations. The Rees and Santee scouts were sent off in advance. Custer’s men left the tipi and looked around the picturesque village. Thirty ponies were grazing nearby, and a good supply of venison hung on poles, drying for Winter use.

Two hours later, One Stab, Slow Bull, Slim Bear, and Long Arm came after their rations. They were kindly received, and their ponies were laden with sugar, coffee, pork, and hard-tack. The Rees, however, still looked upon them “with an evil eye.” The Sioux, for their part, looked askance whenever they saw a Ree.

Another conference was held, but they did not show the “docile spirit” that characterized their previous interview and contradicted much of their previous information.

“I do not trust these Ree,” said One Stab.

“I will send a troop of white soldiers to protect your lodge tonight. In the morning you camp with us.”

One Stab assented and started to leave with his men. They were asked to remain until the white soldiers were ready to go. One Stab agreed and went to the Indian quarters to wait. Custer was barely out of sight when Slow Bull bolted out of camp, in the opposite direction from that which he would naturally take. One Stab and the other warriors also started off. Custer saw that the Ree were uneasy, and he ordered a detachment of scouts after them to ask them back.

“If they refuse,” said Custer, “bring them in by force.”

Determined to send a guard down to protect their camp, Custer dispatched ten men from Company E for the purpose. While they were saddling up, One Stab and Slim Bear, who did not know of this intention, mounted their ponies, and rode off.

“Goose,” yelled Custer, “quick, tell them of the guard and ask them to wait

for it!”

But One Stab and his men were suspicious and would not heed him. Two Santee were then sent after them. They overtook them and told them of Custer’s wishes. It was no use. The fears of One Stab’s men were excited, and they would not return. Red Bird, one of the Santee scouts, seized the bridle Slim Bear’s pony.

“I may as well be killed today as tomorrow,” said Slim Bear, grasping Red Bird’s gun.

Red Bird dropped off his horse, still retaining his gun, and as Slim Bear spurred his pony to escape, took aim and fired. The ball struck Slim Bear’s pony, but he got away. One Stab, however, was taken as hostage, and brought back to camp.

When the guard from Company E reached the village, they found that hours before the women had folded their tents and silently stolen away. A trail leading down to the valley toward the east suggested their direction. Bloody Knife and his men returned scalp-less (having been unable to follow the trail in the dark.) There were howls of disappointment in the Ree section of camp, but One Stab was a prisoner, and was placed under guard at headquarters.

“Explain,” Custer said to One Stab.

“It is all the work of the young bucks,” said the old Chief. “I knew nothing of the flight of my village. The squaws must have been frightened.”

He had then a long private conference with Custer, Custer, unironically, who, unironically, lectured on truthfulness. A mutual understanding was reached.

“You will remain with us and guide us through the Hills,” Custer told One Stab. “When we reach Bear Butte, I will return you to your people, but you must show us a good road.”

One Stab was quite relieved to know that he wasn’t to be tortured and shot, but the expression on his face showed there was trouble on the old man’s mind. “I would be happy if my people only knew that I was alive and well cared for,” said One Stab. He then silently wrapped himself in a blanket for the remainder of the night. [106]

~

It was July 27, and the miners had yet to discover any gold. The “Bug Hunters,” too, whacked in vain for fossils to support the new theory of the “missing link.”[107] It seemed, in the positivist sense at least, that the Expedition was a bust.

It was Ludlow’s daughter, Genevieve’s, sixth birthday that day, and he wished that he could celebrate with her.[108] But the following day they were met with a beautiful surprise.

“Look at that!” said Ludlow, pointing at two unbroken lines of sunflowers.

They were a wagon’s width apart and stretched as far as the eye could see. When Reynolds, passed through these parts fifteen years earlier on his Yellowstone expedition, it must have been here during a time when the sunflowers were in bloom. Reynolds inadvertently assisted their pollination. When the sunflower seeds fell on the unbroken sod of the prairie, they had dried up, but the seeds which fell in the grooves produced from the wheels of wagon trail had sprouted. In consequence, his trail was well-preserved, in magnificent, unending lines of sunflowers.[109]

On July 28, the contingent was most impressed by the discovery of a large (and eerie) pile of elkhorns, several hundred of them, bleached perfectly white, and standing six-feet tall.

“It is doubtless, the Indians votive offering to some deity,” said the Professor. “It would appear that it has been standing many years. It was probably twelve or fifteen feet high when first built but has settled down until it is now only five or six.[110]

Elk Horn Pile.[111]

“Harney’s Peak,” a granite peak that stood above the rest of the mountain, was visible from the top of a high, bare hill. [112] It was named after General William S. Harney who, in response to Sioux raids, massacred Sioux men, women, and children in the Battle of Blue Water Creek in 1855. A swath of bright flame was seen in the sky, and soon after another luminescent swath appeared. It was the moon, masked by heavy clouds, rising just over the southern shoulder of Harney. The moon’s mass looked enormous and bloodred, with only portions of its surface visible. The clouds, just above and to the left, illuminated by the “flame,” resembled smoke drifting from an immense conflagration. The moon soon buried herself completely in the clouds. Ludlow and the men returned to camp under a rapidly darkening sky. [113]

Harney’s Peak.[114]

On July 31, a reconnoitering party consisted of Ludlow, Wood, Custer, Forsyth, and Donaldson, went for some time toward the south end of the Black Hills. There they located Harney’s Peak. [115] Ludlow and a few of the other men decided to climb the peak. They took their horses as high as they could go, then tethered them and went the rest of the way by foot. Custer also went, but he took his horse a good deal higher than the others. After collecting data (and enjoying a wonderful view) they turned around and went back down. Custer’s horse had a difficult time getting down the peak, and its knees began to bleed. More than a few of the men found the ordeal cruel.[116]

~

Camp Where Gold Was Discovered.[117]

In early August, gold was found in camp in the Black Hills. Needless to say, a way of life that had existed since time immemorial was drawing to an end. Even those who did not prospect for gold, were already plotting out their future.

Curtis found that Sgt. Becker of Ludlow’s Engineer Corp. took a fancy to a particular spot, 160-acres to be exact, which he surveyed and staked out.

“Over zer, on ze shaded knoll, I vill put a lager-beer garden.”

“Where are you going to put the house?” asked Curtis.

“Damn ze haus,” said Becker. “Der vill be times enough to dink of dot, anyhow.[118]

Camp was broken for the return trip. Custer decided that instead of going eastward on the prairie, he would retrace his steps and examine the practicality of approaching a northern route through the hills (which would bring them out somewhere near Bear Butte, thereby making a complete examination of the area.)

A day was spent at Bear Butte to collect themselves before striking out for Fort Lincoln via the Little Missouri River.”[119] Bear Butte was an important holy site for the Lakota. It was used for both ceremonies and individual prayer, including the Hablecheya (Crying for a Vision,) prayers for remembrance, and prayers for fertility. It was there, in 1857, where the various divisions of the Lakota nation held a council to discuss the incursion of whites into the Black Hills.[120]

(Left to right) Bloody Knife, Custer, Pvt. John Noonan, William Ludlow.

While camped, once again, in Elk Horn Prairie, Ludlow got the idea to go hunting again.

“Wood,” said Ludlow to his assistant, “let’s go out and see if we can find a grizzly.”