GHOST MOSUKE

ACT III.

X.

⸻

“I belong to the Society because of my personal affection for Madame Blavatsky and Olcott,” Balwantrao told Verochka. They were sitting on the verandah with Noguchi Zenshirō, and Dharmapala, while Charley, Olcott, Harte, and the other administrators were conducting a meeting, or “Council of the Wicked,” as Verochka termed it. It was December 24, exactly seven years since Balwantrao joined the Society, and his mood was somewhat reflective.[1] “What Colonel Olcott takes at face value is in most cases, little more than the natives playing a role,” Balwantrao continued. “I do not place too much weight on the Theosophical movement among the masses of India—they are all unconsciously-selfish…far too accustomed to internecine strife, be it religious strife, tribal, or caste strife, to be completely attached to anything. These ingrained prejudices will destroy the whole country. India is falling to pieces. She disintegrates.”

Balwantrao dearly loved India. There was an undeniable sadness in his voice. Verochka completely agreed with Balwantrao, but, pitying the old man, she, of course, did not express it. Balwantrao was the Secretary of the Poona Gayan Samaj, an organization was founded in 1874 for the “emancipation of classical Indian music.”[2] Seeing the “decadence of the ancient musical science,” and “the substitution of frivolous and sometimes immoral airs and songs,” Balwantrao undertook the heavy burden of reviving “the Aryan melodies.” Undaunted by obstacles, he sacrificed time, labor, and money, to the cause. A prolific man of letters, Balwantrao wrote epistles to everyone, from the native princes to the Prince of Wales, and enlisted the sympathies of successive Governors of Bombay and Madras, and of other influential gentlemen, official and private.[3]

“Do you believe in the Mahatmas?” asked Verochka.

“I consider it a matter of faith, and not obligatory for anyone,” Balwantrao replied. “I have never met a European woman with such a natural and calm demeanor,” he added with a smile.[4]

Then Noguchi told of his story, and connection with the Theosophists. It began a year earlier, in 1887, when his companion, Dharmapala, read an article in The Fortnightly Review titled “A Visit To Japan.”[5] This gave Dharmapala the idea of visiting the “Land of the Rising Sun” himself.[6] The article mentioned the name of “Mr. Akamatsu, a Buddhist priest, who, during a residence of many years at Cambridge, acquired a complete mastery of English language,” so Dharmapala wrote a letter to him, and sent him a copy of Olcott’s Buddhist Catechism. Through this correspondence, Dharmapala was put in touch with Noguchi, a storyteller, whose job it was to relate historical stories at Oriental Hall (an English-language school in Kyoto.)[7] Noguchi, in turn, introduced Hirai Kinzo, the headmaster of Oriental Hall, to the exploits of Olcott and the Theosophists. Hirai Kinzo, a leading member of the Young Men’s Buddhist Committee, decided to raise funds to bring Olcott to Japan and help galvanize the Japanese Buddhists. Hirai sent several letters to Olcott, but he received no reply. Pressure mounted from the Young Men’s Buddhist Committee, whose members were growing impatient. Hirai then dispatched Noguchi to Ceylon om a steamer to personally retrieve Olcott. When Noguchi arrived at the headquarters of the Theosophical Society in Colombo, however, he learned from Dharmapala that Olcott had left the island and gone to London. Dharmapala invited Noguchi to stay at in a room in his parent’s house until Olcott returned to Adyar for the Convention. While he waited for Olcott’s return, Noguchi busied himself by touring Ceylon, where met Shaku Kozen and Kichiren Norihiko, a Jodo Shinshu priest who was studying Sanskrit with Pandit Batuwantudawe.

Noguchi Zenshirō.[8]

Learning that Noguchi was a storyteller, Verochka and Balwantrao implored him to demonstrate his skills. As it was December 24, Noguchi knew just what tale to tell.

“On New Year’s Eve, many years ago,” Noguchi began, “an unknown lady traveler passed through the city of Wakayama, where she died in the street in front of the Fukiagedera Temple. It was learned that she was in the last month of pregnancy. Out of compassion for the unfortunate dead woman, the priest of Fukiagedera Temple chanted a sutra for her, and buried her in the temple graveyard.

“A strange woman soon made nightly appearances in a nearby confectioner to purchase candy. One night, after the woman purchased her sweets and left, the shopkeeper looked casually into the money box. Instead of seeing the money she just placed in the box, he saw the leaf from a tangerine tree.

“Straightaway, the shopkeeper followed after her, but when he got to the wall near the Fukiagedera Temple, she vanished without a trace. The stunned shopkeeper returned home, and on the following day he went to the temple and explained to the priest what he witnessed the night before. The priest, who was also curious about it, accompanied the shopkeeper to the grave of the recently deceased lady traveler, whereby the priest directed his servant to exhume the body. As the coffin was raised from the grave, they were startled by the sound of a baby drying. They removed the coffin lid as fast as they could. Inside they found a newborn baby boy who sucking on a piece of candy. Even after death, this mother’s love was so powerful that she tried to give sweets to her baby.

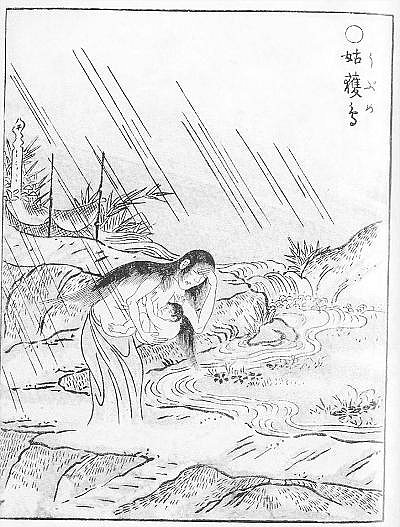

“The child was adopted by the priest and named Mosuke, though the villagers called him ‘Ghost Mosuke.’ Mosuke was a believer in the rice god Inari, the rice god, and when he died the townsfolk made a figurines of his likeness and placed them on an Inari shrine. This shrine came to be known as the ‘Mosuke-Inari,’ and mothers who lacked enough milk offered their prayers of worship, believing that he would fulfill their request.”[9]

Ubume (wiki)

← →

THE AGONIZED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS: “ACT III”

I. TOWER HAMLETS.

III. OCCULTISM OF SOUTHERN INDIA.

IV. THE ONE WHO THINKS HE KNOWS.

VI. WHERE VISHNU SLUMBERS IN HIS SEA-GIRT SHRINE.

VII. THE GENERAL IDEA UNDERLYING THE OPERA

VIII. THE DECAY OF LYING

IX. THE FENIAN

X. GHOST MOSUKE

SOURCES:

[1] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 935. (website file: 1A:1875-1885) Balwant Trimbak Sahasrabudhe. [12/24/81]

[2] Capwell, Charles. “Sourindro Mohun Tagore and the National Anthem Project.” Ethnomusicology. Vol. XXXI, No. 3 (Autumn, 1987): 407–430; Bor, Joep. “The Rise of Ethnomusicology: Sources on Indian Music c.1780-c.1890.” Yearbook For Traditional Music, 1988. Vol. XX. (1988): 51-73.

[3] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume IV. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1910): 77; Bakhle, Janaki. Two Men and Music: Nationalism in the Making of an Indian Classical Tradition. Oxford University Press. Oxford England. (2005): 66, 75-79.

[4] Vera writes: “My dears, today we went to the seaside on a crazy ‘Olkotova’—or rather ‘Theosophical horse,’ which never leaves the place, and after galloping, it will stop again, and, it seems, nothing can be done with it. An idiotic habit. Yesterday Charley attended the ‘council of the wicked,’ as I mockingly call their Theosophical meetings. I sat on the porch late into the night with a Sinhalese gentleman, and a Japanese gentleman, who told me the most amazing stories. There was once a maid in Kyoto, a servant employed in a house near a Buddhist cemetery. This maid began to hear sounds of a crying child in the cemetery, and complained to the local priest of the negligence of the unknown mother. This priest then patrolled the cemetery at night, and, finally, located the source of the crying child—it was coming from one of the graves. The priest dug the earth, and found the body of a dead woman, which, apparently, gave birth to a boy in the grave. This boy was subsequently raised by the priest who found him, and later became a priest himself. He died with the title of Chief Priest of a Buddhist sect known throughout Kyoto for its virtues, and its extraordinary history. There is an old Indian here in Madras named Balwant [Trimbak Sahasrabudhe] (Secretary of the Jubilee Gayan Samaj,) but I could not remember his name and called him either ‘Elephant’ or ‘Bull’—which in English means ‘buffalo.’ He is so big, and fat, and so good-natured, that it suits him well. He is very taken by me, and he says that he ‘has never met a European woman with such a natural and calm demeanor.’ He told me that he belongs to the Society because of his personal affection for his Aunt Leyla, and Olcott, but he does not put too much stock on the Theosophical movement among the natives, because ‘they are all unconscious selfish, and too accustomed to internecine strife—religious, tribal, and caste—to be completely attached to anything.” What Olcott takes at face value, is nothing more than the natives trying, in most cases, to ‘play a role.’ As to the existence of the Mahatmas, he considered it a matter of faith, and not obligatory for anyone. He has been sincerely working for the benefit of Society for twelve years. He is from the Marathi tribe. This tribe inhabits, together with Parsi gentlemen and Mohammedans, the whole of Bombay province, which is larger than Madras. This is an old tribe, and many Englishmen told me on the steamer that the Marathi language is very sophisticated and endowed with a wealth of ancient texts. Poor ‘Elephant Row’ loves India very much; one must see with what sadness he speaks about its disintegration and ingrained prejudices which are destroying his whole country; India is ‘falling to pieces,’ simply crumbling. I agreed with him entirely, but, having pity for the old man, I, of course, did not express it. Indeed, it is hard for a patriot to think that their country has fallen so far, that had it not come under foreign rule, she would have destroyed herself. This is absolutely true. Without the British, and their rule, India would have carved itself to pieces. Jacolliot, as far as I can now tell, has greatly exaggerated the British exploitation of the natives.” [Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” December 25, 1888, Adyar, India, entry.] When Vera writes: “I sat on the porch late into the night with a Sinhalese gentleman, and a Japanese gentleman, who told me the most amazing stories,” she is likely referring to Noguchi and Dharmapala, the latter, according to Noguchi, accompanied him to Adyar. [Noguchi, Fukudo. “My Journey To India 40 Years Ago.” Bulletin of Japan-India Association. Vol. XLII. (November 18, 1927): 71-102.]

[5] Brinkley, V. “A Visit To Japan.” The Fortnightly Review. Vol. CCXLV, No. 5. (May 1, 1887): 676-699.

[6] Kemper, Steven. Rescued From The Nation: Anagarika Dharmapala And The Buddhist World. University Of Chicago Press. Chicago, Illinois. (2015): 135-137.

[7] Kemper, Steven. Rescued From The Nation: Anagarika Dharmapala And The Buddhist World. University Of Chicago Press. Chicago, Illinois. (2015): 137 n. 55.

[8] Barrows, John Henry. The World’s Parliament of Religions: Volume I. Parliament Publishing Company. Chicago, Illinois. (1893): 419.

[9] Iwasaka, Michiko; Toelken, Barre. “Japanese Death Legends and Vernacular Culture.” Chapter in Ghosts And The Japanese. Utah State University Press. Logan, Utah. (1994): 43-124.