Nikolai Ivanovich Achinov (1856-1902,) whom the press described as a “personage something after the type of the redoubtable [Nikolai Notovitch,]” was a Cossack born in Terek, in the Chechen lowlands.[1] At the time, the Cossacks were divided into three tribes: the Cossacks of the Don, the Cossacks of the Islands of the Dnieper, and the Free Cossacks. The last of these tribes, the Free Cossacks, being the tribe into which Achinov was born, were composed of descendants of emigrants from Russia, who, troubled by ill-treatment by Russian authorities, settled in the Caucasus, Turkey, Romania, and Persia. The Free Cossacks were largely Christian, though there were some Muslims, were a confederation governed by a great council known as the Kroug. Comprised of delegates from the various villages, the Kroug, which regulated all the important affairs, elected an officer known as the Ataman who served for life, and who had the power to veto decisions made by the Kroug. In times of peace the Ataman was assisted by a council of eleven persons; he had the power of life and death over those whom he ruled.

Nikolai Ivanovich Achinov.

In 1870, at the age of fourteen, Achinov went to Persia to live with an uncle, under whose supervision he served a military apprenticeship. He earned a reputation for his energy, intrepidity, and sound judgment, which resulted in his appointment to a high office. In 1873 the Ataman sent him to the Governor-General of the Caucasus to broker a deal on behalf of certain Cossacks who proposed to give up lands they owned at Batum and Kars, and establish themselves as a military colony on the Russo-Turkish frontier along the Black Sea, defending that region from enemies. This negotiation was successfully carried out, and the Cossacks took possession of the places assigned to them.

In less than a year the colony fell victim to the intrigues of envious persons in St. Petersburg. The settlers troubled by Russian administrators found life in the colony unbearable, and determined to return to Turkey and Persia. While they were looking for new lands to settle, Achinov was sent to Constantinople. While there he learned from some Cossacks who had just returned from Egypt that the south of that Ottoman province was a fertile country called Abyssinia that was inhabited by old Christians. Achinov endeavored to launch a voyage of exploration to that land in the interest of his brethren, and left Constantinople accompanied by some Cossacks, through the Suez Canal to Massawa, where they arrived in November 1885. Massawa at the time was in possession of the Italians, who received Achinov’s party with civility, and the Italian Governor offering a military escort to the Cossacks. Achinov, however, believing the Italian soldiers to be spies, declined the offer, but graciously accepted the loan of camels to carry their baggage.

Achinov’s party journeyed inland into Abyssinia, stopping first at Asmara where he met Ras Alula, a tributary chief, and his warriors, Achinov then proceeded to the holy city of Aksum, where Abyssinian sovereigns were solemnly crowned in the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion. It was here where King Menilek I was interred, a man who, according to tradition, was the son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Some claimed the site even had possession of the Arc of the Covenant. From Aksum Achinov’s party continued further into the interior, to a place called Amhara, where the Abyssinian Negus (Emperor,) Yohannes IV, was engaged in a conflict with Mahdist rebels. Achinoff was received by the Negus with open arms, and Achinov’s “dauntless courage [and] the charm of his manner, won the heart of the Abyssinian potentate,” who granted to the Cossacks all the lands they desired. In exchange for the permit to establish a colony, Achinov would organize and instruct a military force to serve as a militia for the Negus.[2]

Nine years earlier the Negus sent a letter to Tsar Alexander II through the Russian Consul at Jerusalem. The epistle, in which the Negus stated the desire of the Abyssinian clergy to enter into relations with the Russian clergy, did not receive a reply. Achinov explained to the Negus that the letter arrived when Alexander Gorchakov, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, was ill, and that, subsequently, Tsar Alexander II had been assassinated. Achinov then undertook to obtain from the new Emperor of Russia, Tsar Alexander III, an answer to the letter, and was officially commissioned by the Negus to purchase arms in Europe for the Abyssinian army. Achinov convinced the Negus to gift a priceless relic to the Tsar, the Queen of Sheba’s Cross. The handsome present was venerated in the Orthodox Church, and “unique and unattainable to any other sovereign.”[3] After spending the first two months of 1886 with the Negus, Achinov and his followers returned to Massawa, and from there he sailed to Alexandria, where he left his people and went to Cairo, where he wrote to Tsar Alexander III, explaining the Negus’s proposal, and asking him to accept the Queen of Sheba’s Cross.

When Achinov arrived at Constantinople in May, 1886, he sent a letter to the Negus suggesting that the Queen of Sheba’s Cross be brought to Russia with a deputation of Abyssinian priests to be presented in time for the celebration of the 900th Anniversary of the Christian Church in Russia. This would demonstrate the heritage of the Queen of Sheba (from whom the Negus proclaimed his descent,) while also act as a symbolize of the union between the Church Abyssinia with that of the Russian Church, “both the Greek schismatics—from which it had hitherto been separated by the heresy of Eutyches admitting the exclusively divine nature of Christ and rejecting all belief in the human attributes of the Savior.”[4]

While in Constantinople, Achinov learned that the Ataman of the Free Cossacks had been killed during an expedition against the Kurds, and that the council of the Kroug had been convoked to elect a new Ataman. When the Kroug assembled in June, 1886, Achinov was elected Ataman. His elevation at so early an age, and his success on the Abyssinian mission, made him enemies among the envious, and placed him in the center of numerous intrigues. Nevertheless, Achinov went to St. Petersburg to defend himself against the allegations and accusations. In April 1887 Achinov was informed that the Tsar had agreed to accept the Negus’s gift, and that all complaints against him were dismissed. Achinov then cultivated the friendship of the Negus and the Tsar, the latter eventually deeming it possible to establish Russian influence in Abyssinia. This, itself, was a bit of Russian intrigue, and threatened to disrupt Britain’s progress in Africa. Achinov’s effort was seen as harmonious to the plan of the Tsar’s advisor, Konstantin Pobedonostsev, who wished to support programs that used the Russian Orthodox Church (and its agents) to promote Russian culture, and the interests of the secular Russian state in Abyssinia (as well as the Balkans, Japan, Palestine, and the Americas.) In this way, Pobedonostsev endeavored to create Orthodox communities which would be cultural and political centers for Russia.[5] Furthermore, the Negus’s gift, with its religio-political motive, had the added benefit of upsetting the British.

Achinov soon went to work making preparations for his expedition to Abyssinia. Keeping in mind the great importance the Negus attached to the establishment of relations between Abyssinian clergy and the Russian Church, Achinov laid the matter before the Holy Synod, and the Metropolitan Isidore. Both the Synod and the Metropolitan warmly seconded the desire of the Negus, and gave orders to seek a suitable priest who could be disposed to take the post of Archimandrite and head of the religious mission to Abyssinia. Upon the nomination of Achinov, the position was given to Father Palsi, an ex-warrior of Cossack extraction.[6]

The Negus then sent a special deputation of three Tewahedo priests to Kiev to gift the Queen of Sheba’s Cross. The Abyssinian deputation, however, was delayed on the road. When the three priests of Abyssinia finally arrived in Kiev the ceremonies were over, and the Tsar was back in St. Petersburg. Before returning to Abyssinia, the venerable trio deposited the cross in Moscow in the charge of the high officials attached the Imperial. The Negus waited “with much pride and self-gratulation acknowledgment of this precious gift from his well-beloved friend and brother, the Tsar.” The weeks passed, and still no appreciative Imperial telegram arrived. The Negus, feeling much aggrieved, demanded an enquiry to be made. The Queen Sheba’s Cross never reached its destination. No Russian official could even determine what the question alluded. [7]

Achinov became the talk of the society circles; everyone was talking, either in approval, or disdain, of what was called Achinov’s “Abyssinian Crusade.” It was on a visit to St. Petersburg that the Vicomte de Constantin made the acquaintance of Achinov. The young Ataman took an immediate liking to his new French acquaintance, and before leaving St. Petersburg, asked his interposition with the French Government to sell to the Abyssinians the arms which the French no longer used. The Vicomte acceded to the request, and an agreement was drawn up, and executed. In his efforts to obtain said arms from the French Government, de Constantin showed the written agreement to Charles Floquet, then in charge of French Foreign Affairs. Although no sale of arms was made by the French Government, Floquet made no objection to arms being carried to Abyssinia.

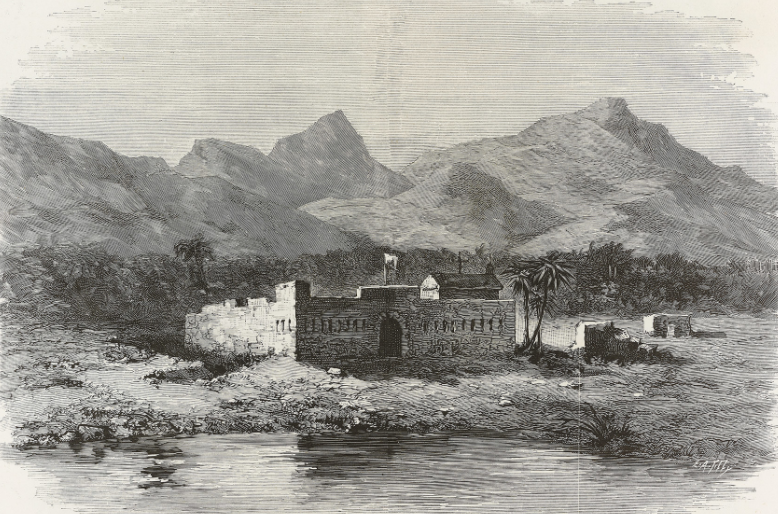

All the preparations for the voyage to Abyssinia were completed, and Paisi was solemnly consecrated to his office of Archimandrite in St. Petersburg. The expedition, conveying 165 men, women, and children, sailed from Odessa, in December, 1888, in the presence of more than 20,000 people. The expedition disembarked at Sagallo, where they awaited the arrival of the escort, and beasts of burden to conduct them into the interior. Here they took refuge in an old fort that was abandoned by the Egyptians, and unoccupied by the French. The party of hoisted a flag adopted by the religious mission, and a small flag bearing the Cross of Geneva used by the Society to Help the Wounded. The French authorities visited Achinov and his colonists, and partook of refreshments offered them, and Cossacks and French relations were of the kindest.

Sagallo Under Russian Control (wiki)

On February 5, 1889, two vessels were seen approaching Sagallo. The Cossacks initially feared that the vessels were English or Italian, but it was determined that they bore the French flag, and their minds were at ease. The vessels cast anchor, and a small boat was lowered, and rowed to the shore. The boat contained a messenger who delivered to Achinov a letter written in French, a language which none of the colonists could understand except the Ataman’s own wife, who, advanced in pregnancy, was then asleep. She was awakened, and began to read the letter aloud, but before she had advanced far enough to gather its purpose, a shot was fired from one of the vessels. The Cossacks were alarmed, but Achinov declared that it was only a friendly salute, and ordered a gun fired in response. A few moments later another shot was fired from the vessels, killing a woman and a child. The French, it seemed, were bombarding the encampment, with no warning, save the letter which demanded surrender, delivered just moments before the cannonade began. Paisi went off to the French vessels, but his protests availed to nothing. Achinov and his Cossack colony were helpless. In the end seven people were killed, two women and four children.[8] The dead were buried. The living, wounded and unwounded, were put on board the French vessels, and carried to Port Said, and from there they sailed home in other vessels.

It so happened that Nikolay Karlovich Giers, the Russian Minister, who had always been opposed to the Abyssinian expedition, exerted his influence to have Achinov punished for proceeding on the expedition. Achinov was sentenced to exile in Siberia for five years on an accusation of trying to create difficulties between France and Russia, At this point the Tsar intervened, and declared that it would suffice that Achinov reside for three years in a government of the interior. In April, 1890, however, Achinov was pardoned.[9]

SOURCES

[1] “An Abyssinian ‘Moscow.’” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (London, England) February 27, 1889.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “London Gossip.” The Birmingham Daily Post. (Birmingham, England) August 24, 1888.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Byrnes, Robert Francis. Pobedonostsev, His Life and Thought. Indiana University Press. Bloomington, Indiana. (1968): 221.

[6] “The career of the new Archimandrite had been remarkable. A Cossack by birth—one of the Cossacks of the Ural—Wasili Ivanovitch by name, he was born of a rich family, in 1822, at Orenburg, on the right bank of the Ural River, some nine hundred miles southeast from Moscow. At eighteen years of age he entered the military service, and for twenty-two years—from 1840 to 1862—participated in all the expeditions of the Cossacks against the Khans of Central Asia, who kept in slavery a great number of Christians, who were Russian subjects. Always conspicuous for gallantry and daring he acquired a good military reputation. He was a soldier after the fashion of Cromwell’s Ironsides. To inflexibility in battle and a keen delight in smiting the enemy hip and thigh, he joined religious enthusiasm. When not sabering or perforating with bullets the subjects of the Khans, he engaged in ecclesiastical controversies or preached sermons to his comrades. After twenty odd years of this kind of work, Wasili Ivanovitch retired to civil life, when he was advised by an archbishop to enter the Church. Acting on this hint, the ex-warrior assumed the name in religion of Paisi, and joined a Russian monastery on Mount Athos, his wife and daughter becoming nuns. He was received by his fellow-monks with enthusiasm, and soon acquired great influence over them. Shortly after the arrival of Paisi, the Archimandrite of the monastery died. Although a large majority of the inmates were Russians, and the institution was almost wholly supported by gifts from Russians, the Patriarch of Constantinople had always put a Greek Archimandrite at its head. Paisi maintained that Russians should be ruled by a Russian, and with the aid of General Ignatieff, then Russian Ambassador at Constantinople, carried his point, and a Russian Archimandrite was elected. Not long after this he, with the aid of large contributions from Russians, established at Constantinople a hospice, or refuge, for pilgrims to and from Jerusalem and Mount Athos, and over this hospice he had presided for nearly twenty years.” [“L’Archimandrite Païsi Et L’Ataman Achinoff.” Literary Digest. (August 22, 1891): 18-19.]

[7] “London Gossip.” The Birmingham Daily Post. (Birmingham, England) August 24, 1888.

[8] The Encyclopaedia Britannica. (Eleventh Edition.) Vol. XXIII: Refectory to Saint-Beuve. The Encyclopaedia Britannica Company. New York, New York. (1911): 1,001.

[9] “L’Archimandrite Païsi Et L’Ataman Achinoff.” Literary Digest. (August 22, 1891): 18-19.