A Tournament Of Shadows:

VIII. At Heart A Friend Of France

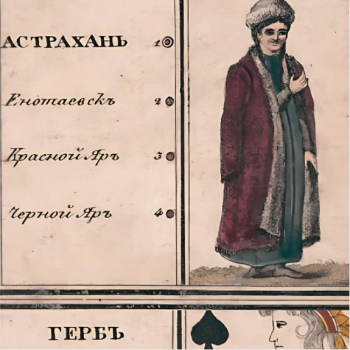

Tsar Pavel Petrovich, against the wishes of his late mother, took punitive measures against Persia after Russia’s victory over them. Lacking his mother’s experience and tactfulness, Tsar Pavel signed the proclamation on the annexation of Georgia to the Russian Empire in December 1800, finalized by a decree on January 8, 1801.[1] A month later, in March 1801, Tsar Pavel Petrovich was assassinated—strangled in his own bed.[2] The annexation was confirmed, however, by his successor, Tsar Alexander Pavlovich, on September 12, 1801. Persia officially lost control over the Georgian lands it had been ruling for centuries.[3] The new commitment, accepted only reluctantly, to deploy forces in Transcaucasia and integrate the territory into the administrative structure of the empire, resulted in the creation of three provinces in 1802: Astrakhan, Caucasia, and Georgia, with capitals in Astrakhan, Georgievsk, and Tiflis.[4] (Tensions with Persia would soon resurface, prompting a reawakening of Russia’s interest in Transcaucasia and resulted in the nine-year-long Russo-Persian War.)[5]

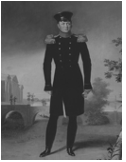

Tsar Alexander Pavlovich.

Alexander Pavlovich was a tall, straight, very slender youth of twenty-three. His chestnut-colored hair was short, thick, and curly, and styled in the regulation military pigtail (which he soon abandoned.) His face was more “boyish” than usual for a man his age, with a soft complexion and total absence of facial hair. His searching eyes betrayed a deficiency, one which obliged him to use strong glasses. A cloud of melancholy and uneasiness seemed to blanket him despite the wisdom and humanity of his advisors. He could hardly conceal the gloomy moods that came over him and often rode away from his aides-de-camp to wander miles alone over the country. When he was in St. Petersburg, it was not uncommon for Alexander Pavlovich to plunge into the deserted streets at night and walk until daybreak. Yet this temperament, a life weighed upon with the power of remorse, did not detract from the energy with which he performed his Imperial duties, and he showed an almost feverish impatience in pushing forward his social reforms (of which there were many.) Thomas Jefferson, sworn in as America’s third President two weeks before the coronation of Alexander Pavlovich, had high hopes for the young Tsar. “The apparition of such a man on a throne is one of the phenomena which will distinguish the present epoch so remarkable in the history of man,” said Jefferson, “but he must have a Herculean task to devise and establish the means of securing freedom and happiness to those who are not capable of taking care of themselves.”[6]

Alexander was raised by his grandmother, Catherine the Great, who, in many ways, fashioned him in her image. While Catherine expanded the Russian Empire and transformed it into a true superpower, she also initiated several liberalizing reforms. Among the policies that endeared her to her people, there was a reduction in the powers of the clergy, improvements in education, establishment of a system of local governments. In addition to modernizing the country, she was a patron of the arts. Though she wanted to continue these liberal reforms and territorial expansions through her son, Tsar Paul, she accepted that he would ultimately fail both her and Russia in this regard. She loathed his lack of vision, less-than-remarkable intelligence, and meddling pedantry. Catherine, instead, focused her attention on her grandsons, Alexander and Constantine, the sons of Pavel and Maria Feodorovna.

Catherine loved Alexander, and actively planned for him to succeed her to the throne. (There was no law of primogeniture in Russia, and the reigning monarch chose their successor.) She saw in Alexander all the qualities her son lacked, that is, he was precocious, gifted, and handsome. Catherine raised Alexander in Spartan conditions so he would know the hardships of his people, and his bedroom window was always left open so that he would feel and know the cold of a Russian winter. She ordered the nearby regimental batteries to fire their cannons and shout their orders loudly so that Alexander would hear them and gain an early sense of the cadence of military life. (Owing to this, he lost the hearing in his left ear.) Even had this not been the case, his sleep would still have been unpleasant, for his bed was made of straw and thick leather. Adversely, Catherine also dressed him in the finest clothes and exposed him to fine art, great literature, and cultivated within him an appreciation of high society and courtly etiquette. When Alexander turned twelve, Catherine placed his education in the capable hands of the Swiss tutor Frederic La Harpe, a Republican by training, and friend of philosopher, Jean-Jacque Rousseau. La Harpe emphasized teaching Alexander Pavlovich the liberal arts and humanities over math and science and taught him the foundational principles of the Enlightenment. The Tsarevich would learn five languages but excelled in French (the language of international diplomacy,) which became his preferred language. Under La Harpe’s tutelage, Alexander Pavlovich developed a strong sense of egalitarianism and the recognition of much-needed liberal social reforms.

The two main philosophical schools at this time were the Rationalists and the Empiricists (the latter being the most closely tied to Enlightenment thought.) Other philosophies flitting around were Materialism, a philosophical monism that believed that matter was the fundamental substance of nature, which every and all things were predicated.) There was also Sentimentalism (a precursor to Romanticism,) which placed a premium on emotions over reason as the basis for an individual’s actions (and reactions.) While the Rationalists had an “outside-in” approach, believing that reason alone was enough to “know” the world. “I think,” said the Rationalist, René Descartes, “therefore I am.” The Empiricists (largely English and Scottish philosophers) relied more on data in an “inside-out” approach. It was through experience that humans could “know” the world. “Science is the knowledge of consequences, and dependence of one fact upon another,” writes the Empiricist, Thomas Hobbes. (He also said that “Curiosity is the lust of the mind.”) Fellow Empiricist, David Hume, drearily claimed that “the life of a man is of no greater importance to the universe than that of an oyster.” Rousseau belonged to another philosophical camp, Sentimentalism (a precursor to Romanticism,) which placed a premium on emotions over reason as the basis for an individual’s actions (and reactions. His Discourse On Inequality (1755,) argued that private property was the source of inequality, and in The Social Contract (1762,) he outlined the basis for legitimate political power. “Since no man has any natural authority over his fellows, and since force confers no right, conventions remain as the basis of all legitimate authority among men.” Political society, not being simply an aggregate of isolated men, but rather various associations organized and possessing public property. The act by which a people became a people was the foundation of any given society, and it is on this first (unanimous) convention on which rested the obligation of the minority to submit to the majority. This convention is only obligatory because it is formed when people have reached a point at which the perils that endanger their preservation in the natural state compel them to band together and overcome the limitations they as individuals can exert. The understanding is that this deal is the most beneficial for the majority of people and that the State should work for both the people and those in power.[7] Then there was Immanuel Kant, who tried to merge Rationalism and Empiricism. Humans, according to Kant, rationally categorized the world but also imposed their structures on the world. In this understanding, humans are not passive observers of reality, but rather agents who actively make reality conform to our categorizations.

Catherine the Great then selected the woman whom her grandson would marry. After a long search in the royal courts across Europe, she settled on a young and beautiful German princess named Louise of Baden, a smart and charming (though not particularly forceful.) They were married in a grand ceremony in St. Petersburg in September 1793. They would have two daughters, their only children, but both would die before reaching adulthood.

The Tsarevich, to put it mildly, was also a “romantic,” and was a “romantic” with a succession of mistresses. Arranged marriages such as this were almost never predicated on love, but his relationship with Elizabeth would eventually develop into true friendship which only deepened through the years. As the Tsarevich neared adulthood, he asserted a will independent of his domineering grandmother and increasingly reverted to the influences of his parents. From his father, Tsar Pavel he developed a love for military drill and procession, and from his mother, he learned the art of tenderness and mercy.

When Catherine the Great died unexpectedly in 1796, and Pavel Petrovich became emperor of Russia, it soon became evident that he would not be able to hold up his end of the “social contract.” He ruled the empire as a petty tyrant and reversed many of the reforms and policies of his mother. He viewed the French Revolution as a threat, so he censored the people by limiting free speech and preventing access to certain literature. He then increased the powers of the (much despised) secret police. Even his closest advisers soon agreed that the Tsar would have to be removed from power to save the country—be it exile, forced abdication, or murder. Perhaps Alexander Pavlovich agreed to the plot to arrange his father’s exile, but he never agreed to the conspiracy that killed him. Nevertheless, in March 1801, his father, the Tsar, was bludgeoned to death in his bed, by his guards. Maria Feodorovna immediately blamed her son for the murder (but she later changed her mind when more details emerged.) Alexander Pavlovich was as stunned as anyone by the tragedy and blamed himself for not saving his father’s life. The stain on his conscious regularly drove him to moments of deep anguish for being an unwitting accomplice in the assassination. Alexander was a man haunted.[8]

Though he took every step to show his respect for his father’s memory, he remained perfectly consistent with his youthful admiration of the French Revolution (and the spirit which had made him induce his father to acknowledge the government of the Republic.) Tsar Alexander Pavlovich wrote to Napoleon on his accession, expressing his wish to continue on peaceful terms with France. He had experienced first-hand the evils of a hereditary despotism. Napoleon having also seen by experience the evils of Republicanism, and the superior power that a despot enjoyed over that of a President of a democracy dependent on the will of the people, could not believe that Alexander Pavlovich was sincere. “Who had ever seen a really liberal autocrat or a sovereign willing to curtail his privileges for the benefit of mankind?” Napoleon could not credit such an anomaly to the Tsar, nor could he comprehend the disinterestedness in a man born to the position which he coveted above of all else. Alexander Pavlovich, however, possessing a depth of understanding in his enlarged quick perception of things, was no ordinary Tsar (which even his detractors acknowledged.) Few would dispute that he was one of the noblest characters of modern times.

Napoleon had not ventured to unite Piedmont to France while Tsar Pavel Petrovich, but as soon as he learned of his death, he took possession of it. Alexander Pavlovich ordered the Russian Minister in Paris, M. Kalitschev, to complain of this breach of faith. He was told that Napoleon was angry at the lack of respect that the King of Sardinia had shown to him. Napoleon immediately sent General Géraud Duroc on a secret mission to St. Petersburg, to try and conciliate the Tsar, but ostensibly to congratulate him on his accession.

“I am at heart a friend of France,” Alexander Pavlovich told Duroc. “I have admired your new ruler for a long time. He has strengthened social order in Europe by establishing authority in your country. I willingly concede to him all that he has conquered, even Egypt, though this conquest brings France too near to Constantinople, and weakens the Ottoman Empire still necessary for the equilibrium of the world; but I should prefer Egypt to belong to France rather than to England. I renounce the island of Malta and the superannuated idea of reconstituting under my protection an institution deceased with the superstition which gave it birth. I would even yield to him Piedmont without a dispute provided that he indemnifies my old ally the King of Sardinia. As to England, I am as interested as you are in not making over to her the liberty of the seas, the only guarantee of my immense commerce with her and with the maritime Powers. I would willingly come to an understanding with you to limit or check her. I interest myself very little in the great Powers of Germany, who deserted her own cause by her egotistical negotiations, like Prussia, and her want of energy on the field of battle, like Austria at Zurich. These Powers may feel the fatal consequences of their perfidy and their cowardice. I shall not make war for their glory. Treat with them as you choose, only tell the First Consul (Napoleon) to regard appearances, to limit his conquests to the treaties he has made, and not to furnish Europe or my own ministers with ground for declaiming on his insatiable ambition, and for drawing me in spite of myself to oppose him in my quality as the born protector of the weak and the oppressed .”

On another occasion Alexander Pavlovich told Duroc that his removal of the embargo his father laid on English vessels was only strict justice.

“I have no intention of becoming a satellite of England. It depends entirely upon the First Consul whether I shall continue to be his ally. I am bound to the Kings of Piedmont and Naples by treaties. I am conscious their conduct has not been straightforward; but how were they to act hemmed in as they were and domineered over by England? The seizure of Piedmont and part of Naples was unworthy of the ambition of the First Consul and tarnished his glory. It gave alarm to the minor princes of Europe, who were continually importuning Russia; but if these difficulties were removed—France and Russia might in future keep up a good understanding.”

The Tsar stressed that France must not take advantage of the weaker Powers, and their inability to resist her; for by the treaty of Teschen in 1779 Russia had guaranteed the independence of the smaller States of the German empire; but that Austria and Prussia should be able to defend their own interests. Consequently, the French Government began to secretly purchase the allegiance of the smaller German States, so that without technically defying their protector Russia, she might procure their voluntary alliance and use them as outposts for the intimidation of Austria and Prussia. If Napoleon was mistaken in his estimation of Alexander Pavlovich, the Tsar was equally mistaken in Napoleon.

Lacking the knowledge that comes with experience in the world, the young Russian who had never left his country, imagined that the faults he saw in his own people were peculiar only to them, and not shared humanity at large. It was a sincere belief that just beyond the Elbe and the Rhine, there was the Utopia that his foreign tutors and the old French and German authors loved to portray. He believed in the powers of the Revolution and thought he saw in Napoleon the champion of liberty and the son of the French Republic which had proclaimed freedom to the oppressed and cast from its borders the worthless nobility were doing their utmost to corrupt his people. The Inquisition was abolished in Northern Italy through Napoleon’s victories, and Alexander Pavlovich regarded the Catholic religion as the “superannuated ally of tyranny,” and looked upon its overthrow and the stability of the Greek Church as not simply a blessing to mankind, but a national triumph. The doctrine that forty millions of men, thought the young Tsar, was certainly worth more than one Sovereign, and was the only basis on which he could excuse his accession. This was a principle not held by his fellow monarchs, but he nevertheless adopted it as his motto, rejecting the notion that kingdoms were private estates vested in royal families. “A prince is but the servant of the State,” he maintained, “and he who is most popular, and most capable of reigning, is the one who ought to be placed on the throne.” He hoped to erase the dark commencement of his authority by bestowing benefits on his people (and the world at large) by the superiority of his government to that of his unfortunate father.[9]

SOURCES:

[1] Ledonne, John. “Building An Infrastructure Of Empire In Russia’s Eastern Theater, 1650s-1840s.” Cahiers Du Monde Russe. Vol. XLVII, No. 3. (July-September 2006): 581-608.

[2] Blavatsky, H.P. “The Assassination of the Czar.” The Pioneer. (Allahabad, India) April 9, 1881.

[3] Kelly, Walter Keating. The History Of Russia: From The Earliest Period To The Present: Vol. II. Henry G. Bohn. London, England. (1855): 197.

[4] Ledonne, John. “Building An Infrastructure Of Empire In Russia’s Eastern Theater, 1650s-1840s.” Cahiers Du Monde Russe. Vol. XLVII, No. 3. (July-September 2006): 581-608.

[5] Ledonne, John. “Building An Infrastructure Of Empire In Russia’s Eastern Theater, 1650s-1840s.” Cahiers Du Monde Russe. Vol. XLVII, No. 3. (July-September 2006): 581-608.

[6] “From Thomas Jefferson To Joseph Priestley, 29 November 1802.” The Papers Of Thomas Jefferson. Vol. XXXIX: 13 November 1802–3 March 1803. (ed.) Oberg, Barbara B. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. (2012): 85–87.

[7] Rousseau, Jean-Jacque. The Social Contract: Or, Principles of Political Right. Swan Sonnenschein & Co. New York, New York. (1895): 42-44. [Introduction by H. J. Tozer, 1-96.]

[8] Bennett, Richard E. 1820: Dawning Of The Restoration. Brigham Young University. Provo, Utah. (2020): 57‒80. [Chapter Three: “Tsar Alexander I: The King Of The North And His Holy Alliance.”]

[9] Joyneville, C. Life And Times Of Alexander I.: Emperor Of All The Russians: Vol. I. Tinsley Brothers. London, England. (1875): 165-171.