In this week's Torah portion, Chayei- Sarah, we meet Rebecca, Isaac's soon-to-be wife. In Anita Diamond's, The Red Tent, Rebecca is a powerful Oracle, while Isaac is a blind fool. Diamond's Rebecca is the foil to her husband; she is all seeing and he sees nothing. The Midrash Diamond created for Rebecca is on target. Rebecca is the freest woman in the Torah. In the Torah's text, like in Diamond's text, Rebecca becomes the inverse of her husband; she is free because he is not. Isaac may have survived an attempted human sacrifice, but he remains always a sacrificial animal. He is the only patriarch who lives his life entirely in his birthplace; Isaac stays put, both physically and proverbially, while Rebecca emerges out of the vacuum created by Isaac's holy stasis.

Rebecca is the orchestrator of her own fate. When Abraham's servant, Eliezer, shows up in her hometown, she, famously, offers him and his camels water from the town's well. The servant set her up; by this act of talking to a strange man and offering him water, Rebecca passes Eliezer's test for selecting Isaac's bride. Traditional commentaries see Eliezer's test as a way of ascertaining kindness. However, passing the test also required boldness—surely a woman in Rebecca's time and place was warned repeatedly not to talk to strange men sitting at the public well. Rebecca may have been kind, but in the Torah, boldness was a required characteristic for the wife of Abraham's fragile son. Rebecca's boldness and initiative goes beyond the well, to her marriage negotiations. She is an active party in the negotiations; the choice to marry Isaac is made by her.

"Let us call the maiden and ask her decision . . . Will you go with this man?"

And she said, "I will go." (Gen. 24:55-58)

After she marries, decades pass, and like the rest of the matriarchs, Rebecca is infertile. Finally she conceives, and remarkably, Rebecca does what no other woman dared to do, she "inquires of God" (25:22). She is the only woman in the Torah to inquire of God without the use of intermediaries and then to receive a response directly from God. She inquires of God regarding her difficult pregnancy and God tells her that she will be the mother of twins, who will become two separate warring nations.

However, even her direct connection with the Divine voice does not save her from having to resort to trickery to effectuate the prophecy that God showed her. She orchestrates an elaborate ruse to trick her blind husband into blessing the younger twin, Jacob. Why couldn't Rebecca simply go to Isaac and tell him about the prophecy she received during her pregnancy. Why did she need to instruct Jacob to lie and pretend to be his brother Esau? And why doesn't Isaac, the giver of the blessing, receive the prophecy in the first place? Traditional commentators suggest that either Isaac must have really known or that this was the only way to get Jacob out of Canaan and back to his mother's family, where he would become a nation. However, neither response escapes Isaac's unwillingness or inability to move the narrative along. History happens to him. Rebecca is necessary to this story—she must be what Isaac is not. However, the only way to do that is to go along with the patriarchal fantasy. Isaac, who is clearly not in charge, who has no divine vision or earthly ability to read his children, is still the giver of the blessings. Even the free Rebecca is still a trickster.

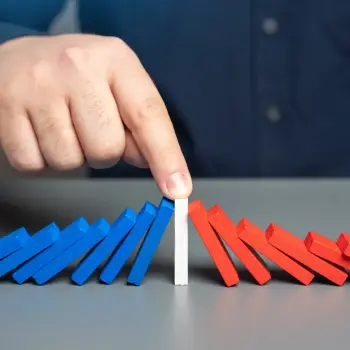

In the Torah's text, the space for free women to exist is opened up by the chaos left behind by feeble men. When men are unable or unwilling to act, women step in. And thus women's agency is directly connected to men's lack of agency—as if there is only so much agency to go around. It is as if freedom is a natural resource, where a measure is granted to every couple. Rebecca and Isaac represent this false dichotomy, which continues to reverberate today. In this archetypal narrative, we see the myth of the powerful woman and the whipped man. However, for Rebecca to be an Oracle, Isaac does not have to blind—there are eyes enough for all.

11/17/2011 5:00:00 AM