We don't have a fireplace, and I had been warned by many concerned relatives that we were in a dangerous position should we lose power with the approaching ice storm and subsequent below freezing temperatures. Everyone gets excited about a storm—the weathermen, grandparents, my 4-year-old. Even I felt invigorated with a delightful sense of new purpose.

We don't have a fireplace, and I had been warned by many concerned relatives that we were in a dangerous position should we lose power with the approaching ice storm and subsequent below freezing temperatures. Everyone gets excited about a storm—the weathermen, grandparents, my 4-year-old. Even I felt invigorated with a delightful sense of new purpose.

Storms are an event, a call to action, in which the rightful occupations of one's time are self-evident. There are things to do in preparation: wash everybody's hair in anticipation of days without water, go to the store for trail mix and bananas, charge the batteries, fill the tanks. We did all those things, and then piled the kids in the car and went to my parents' house. They have two fireplaces, and lots more space for stir-crazy kids.

In the morning we awoke to a world encased in ice, like opening up a geode or a jewel box, so we took the kids for a walk down in the lower field and up through the woods. The air was surprisingly mild and our boots broke through the ice-glazed cowpie like the sugary crust of a crème brulée.

We toasted the remainder of the day with hot chocolate, books, and chicken noodle soup. It was one of the better February afternoons in recent memory. And the icing on the cake: after we cleared the table, but before the washing up, the power went out—the moment for which we'd been waiting. We gleefully lit the oil lamps and nearly every candle in the house, and sat down on the couch, listening to the wind. Now what?

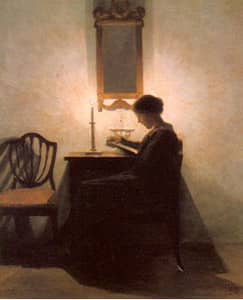

Sometimes my husband and I play Euchre with my parents, but the old-timey movies and "Little House on the Prairie" episodes really deceive viewers about the amount of light a few oil lamps and candles provide. One lamp might provide light for one reader, but it doesn't illuminate a room, so my mom read some Cautionary Tales to the children, we said the Rosary, and then we went to bed, not much after eight o'clock.

My husband and I slept on the pull-out couch by the wood stove, children nearby under heavy comforters. Every two hours, someone had to put a log on the fire to keep the house warm, and I passed a large portion of the night reading Gilead by lamplight.

On the following day, there was less sun. We heated water on top of the stove for instant coffee, which I must admit was terrible. Throughout the morning, people carried buckets from the bathtub to the upstairs toilets where gravity did the flushing. We washed our faces with baby wipes. My dad brought in more wood. And getting fidgety, the kids started to fight with one another.

I have always harbored fantasies about moving off the grid, becoming self-sufficient, embracing a more difficult way of life. It's one of those fantasies that floats in an evanescent halo of unreality, in which I always appreciate life's beauties and bounties because they have been hard-won by the toil of my own hands. See the wisp of hair fall out of her bun as she churns the butter. See the children assist their father with the milking. See the family gather around the fire in the evening with a banjo to sing songs about dewy meadows and broken hearts.

As my father said, living without power is fun for about twenty-four hours. But after jigsaw puzzle and book, after roasting hotdogs in the living room for lunch, after half-dozen arguments with the kids about keeping out of one another's space—there's not much more to do than wait. For a moment, I recognized the fulfillment of a dream of simpler living and forced togetherness, and I felt a little superfluous.

One night in the car, NPR broadcast a talk show called "Humankind." I'm not one to change the dial when soothing disembodied voices talking about religious experience come roiling out of the ether. It was an encore broadcast of an interview with a long-dead Taoist from Kansas. He talked about the symbol of the yin yang and how being is a flow of opposites, light/dark, rest/work, etc.

I think this is a concept that the Church and Christianity decidedly "gets," considering liturgical cycles of fasting and feasting, and the elevation of suffering in the work of redemption. I know it's the conclusion I'm supposed to reach after being forced to live without: that modernity has its perks and I'm as dependent on them as the next person; that systematic and voluntary deprivation, abstinence, in short, makes the heart grow fonder. I already knew all that.

Midway through my life's journey, I'm faced with a question I didn't know I'd be asking at this stage in the game, because it's a question to which I thought I knew the answer. After addressing relatively early in life Whom I would worship and what parameters would apply to my life because of that decision, I still at times find myself wondering exactly how I should live. Certain decisions I've placed in the hands of God—like "How many kids will we have?" and "How will we sustain them?"—those central questions have been answered, for today.