- Trending:

- Pope Leo Xiv

- |

- Israel

- |

- Trump

- |

- Social Justice

- |

- Peace

- |

- Love

The 100 Most Holy Places On Earth

Po Lin Monastery

Associated Faiths:

Buddhism

Accessibility:

Open to visitors.

Annual visitors: 1,000,000

History

A little over a century ago (in 1906), three Zen masters visiting from the Chinese mainland started what would become the Po Lin Monastery on the island Lantau (of Hong Kong). Initially named the “Big Hut,” its current name—Po Lin (meaning “to approach”)—was given it in 1924. In 1918, a private convent was built on the site. In the mid-20th century, it housed approximately 20 nuns and lay persons. Today, a singular person maintains the women’s abbey.

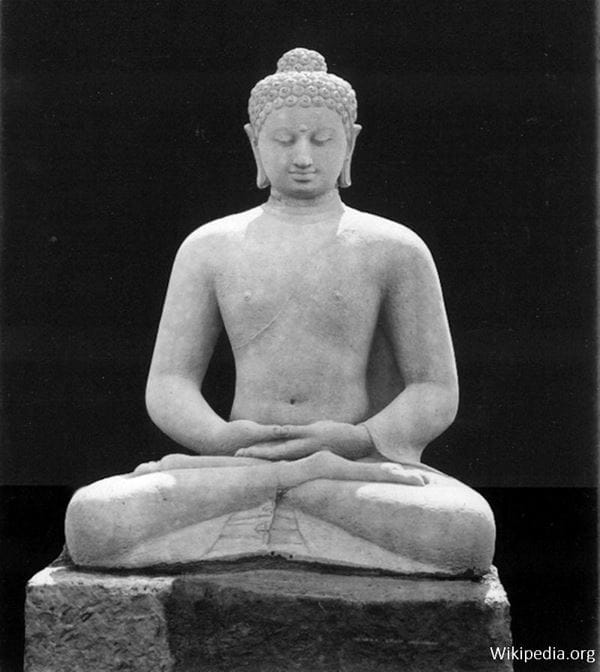

On the site of the Po Lin Monastery is the famous bronze Tia Tan Buddha, also known as the “Big Buddha.” While Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana Buddhism all have a presence in Hong Kong, the Tian Tan Buddha (built between 1990-1993) clearly evidences Vajrayana influence—as mudras stated with Tibetan Buddhism (and this buddha is depicted with his arms and hands conveying a mudra). The Tia Tan Buddha stands 112 feet tall and is the largest outdoor statue of the Buddha in seated position anywhere in the world. It is so large that the Buddha’s fingers are each larger than a human being. Depicting the Abhaya mudra, which is associated with protection and fearlessness, the Big Buddha is said to be a symbol of Hong Kong’s immovability, but also representative of the connection between nature and humankind as well as people and their relationship with belief.

In the “Hall of the Great Hero,” which is the main temple (at the monastery), there are three bronze statues—“golden Buddhas”—which are, according to some, symbolic of Buddhas of the past (on the left), the present (in the center) and the future (on the right). Others see these three prominent statues as representing Sidhartha Gautama’s past, present, and future lives.

The path to the monastery is called the “Wisdom Path,” and it is lined with thirty-eight columns. Thirty-seven of those pillars are inscribed with part of the ancient “Heart Sutra”—reverenced in Buddhism, but also by some Taoists and Confucianists. The 38th column is left blank, symbolic of the idea of Śūnyatā or emptiness.

Religious Significance

In achieving enlightenment, Sidhartha Gautama learned the “Four Noble Truths,” often encapsulated as follows: 1. Life is dukkha or suffering; 2. Suffering comes because of craving, desire, and attachment; 3. Craving, desire, and attachment can be overcome; 4. The Noble Eightfold Middle Path is the means of achieving freedom from suffering. While more pronounced in Theravada Buddhism, practitioners of various Buddhist sects believe in the principles encapsulated by the Four Noble Truths. As a consequence, a sacred site such as the Po Lin Monastery has the overarching purpose of facilitating freedom from dukkha and, as a consequence, freedom from the cycle of reincarnation (or saṃsāra). This alone makes the monastery and the Buddha which rests there a “sacred space” geared toward the accomplishment of the primary purpose of life—enlightenment.

Many Buddhists believe that there are some 108 “vexations” or “distractions” that prevent us from achieving enlightenment. These are things which all humans must intentionally combat and overcome if they wish to become “awakened” or find within their personal “Buddha nature.” Thus, in the Po Lin Monastery, 108 times each day, a large bell—with Buddhist figures and prayers engraved thereon—is rung in the temple, reminding all who attend of the need for conscious and calculated efforts to live the Eightfold Middle Path, thereby overcoming these “distractions” which “vex” our skandhas (or “impermanent souls”) and prevent us for achieving release.

The Tian Tan Buddha sits upon a lotus flower—often understood in the Dharmic faiths as a symbol not only of purity, but also of divine origin. Thus, as pilgrims and visitors approach the Po Lin Monastery and its 112-foot imposing bronze Buddha, one is reminded of Sidhartha’s achievement of perfect purity in desires, and his realization of what one can almost call a “divine status.” The Buddha looks down upon visitors with a glance of calmness and strength. He is a reminder to the contemplative visitor that the Buddha found the way and has revealed the way off the “wheel” of saṃsāra (or reincarnation)—for all who wish to follow it. With his mudra of protection and fearlessness, he stands as a reminder to all Buddhists that there is spiritual safety in the Four Noble Truths. And that “sacred space” can be the very thing which starts one on the journey to holiness.