Editors' Note: This article is part of the Public Square 2014 Summer Series: Conversations on Religious Trends. Read other perspectives from the Progressive Christian community here.

Earlier this year, I blogged my hunch that this would be the year of the Bible. I felt we were reaching a tipping point after which the cat would be out of the bag, by which I meant that important conversations about the Bible would escape from the seminary classroom to the local congregation. With important releases by Adam Hamilton, Peter Enns, Steve Chalke, and many others (including, I hope, my newest book), that hunch seems to be coming true.

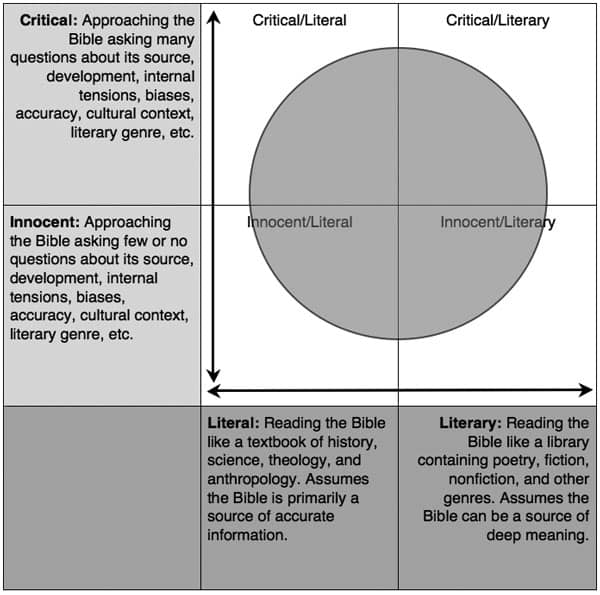

Many people, of course, think there are only two ways to read the Bible: their way and the wrong way. But there are actually multiple options, as this matrix shows.

Within these four general categories, there are countless locations or points of view, and many of us move back and forth from one quadrant to another, depending on our mood or context.

There's one other feature to the diagram that's relevant to ways the Bible is being re-thought. While some people read the Bible as an academic or intellectual exercise only, many of us—as indicated by the shaded circular space that overlaps all four quadrants—read it with some sense of personal need, maybe even desperation. In this circle, we are seeking guidance and wisdom for how to live our lives because we are aware that as individuals, families, communities, nations, and civilizations, we are always on the verge of tipping over into self-destruction.

In other words, those of us in the gray circle aren't primarily seeking information from the Bible. Rather, we're seeking meaning, hope, guidance, perhaps even salvation from something that threatens to destroy us. And—dare we say it?—we may even be seeking revelation, some encounter that gets our minds into realities too big to be contained within our minds. We feel ourselves to be in trouble, in a predicament, on a quest, and we're ever vigilant for news that might help us cope with the mysteries and challenges in which we find ourselves. So the shaded circle represents a personal or predicamental approach, as opposed to merely an academic, doctrinal, analytic, political, or informational approach. It can bring people from all four quadrants together.

As a boy, I was introduced to the Bible from the lower left quadrant. When I got older, I moved to the lower right quadrant and gained new insights. I was never attracted to the upper left quadrant, but I read many authors who wrote from that quadrant. From them I gained the freedom to apply critical thinking to this text that I had come to love. Finally, I found myself at home in the upper right quadrant, where I can enter the Bible as a library, a literary collection containing poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and other genres, and where I have complete freedom to ask questions about the Bible's sources, development, internal tensions, biases, accuracy, cultural context, and genre. In my movement from quadrant to quadrant, I have remained in that shaded circle of reading personally, because I still feel myself deep in the mysteries, dangers, and wonders of the human predicament.

From this space, I don't need to presume agreement among writers. I can allow them to make statements and counter-statements, to agree and to disagree. Similarly, I don't need to assume every detail in the library is factual. Instead, I can read with the assumption that ancient storytellers had aims other than journalistic objectivity, scientific accuracy, or even absolute clarity.

This personal/critical/literary approach has freed me from the need to defend the violence found in the Bible, often attributed to God. It has also freed me from the opposite extreme: the need to throw out the Bible because it contains this violence. It has allowed me to trace how violence and the idea of God are gradually disentangled through the course of the biblical narrative, leading to a radically gracious and nonviolent vision of God. With a personal/critical/literary approach, I can see how our ideas of God have always matured as we matured, which challenges me to keep maturing now.

Of course, plenty of people tell me I'm not allowed to read the Bible in this way. To them, anything other than innocent/literal belief is nothing but unbelief. I try to respond politely but firmly: You are free to read the Bible literally and innocently if you prefer, but you don't have the authority to force everybody else to do so. If they push harder and claim that authority, I reassure them that my problem is not with the Bible's authority, but with theirs.

The Bible—and the same could be said for the Quran or any other sacred text—is too good and too important to be left to those who won't think critically about it. And frankly, it is too dangerous.

As this fresh conversation about the Bible makes its way from seminary classrooms into local congregations, people will discover that reading the Bible with personal engagement, critical thinking, and literary skill yields more joy, more insight, more wisdom, and, yes, more revelation than before.

6/18/2014 4:00:00 AM