Editors' Note: This article is part of the Patheos Public Square on Faith and Reason. Read other perspectives here.

According to the poet Wallace Stevens, "It is the belief and not the god that counts." This rather Kierkegaardian "gospel" evokes the traditional tension that marks, and often mars, the affiliation between faith and rationality, a tension that arouses specific questions. Should one reduce what "counts" theologically to a checklist of acceptable doctrines that rationally delineate some sanctioned sacred system of thought? Does one have to prefer either defining faith as a collection of theological propositions with identifiable and verifiable evidentialist algorithms of attestation or defining faith as an expression of fiduciary passion that celebrates sentiment and sincerity in a silence of substance? Does one have to articulate straight opinions about how to characterize the divine in order to avoid the damnation of error and misinterpretation? Does God — s'il y en a, "if there is such a thing" — genuinely give little credence to our feeble creeds and simply desire only our categorical commitment? In other, more conventional, words, should one maintain a distinction between fides qua, faith as verbal — as the act of believing — and fides quae, faith as nominative — as the content of what is believed — and, furthermore, privilege one of these distinctions over the other?

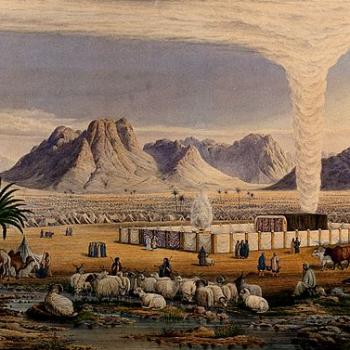

Obviously, Stevens opts for separating devotion from dogma, thereby inoculating faith from the infection of rational knowledge, or logical justification, or epistemic certainty. In doing so, he apparently tracks the hermeneutics of faith espoused by the Apostle Paul, the French philosopher Jacques Derrida, and the American theologian John Caputo. The former clearly and boldly separates the risk of a tenebrous faith from the security of an enlightened rationality: cf. for example, "For we walk by faith and not by sight" (2 Cor. 5:7) or "For we know in part and we prophesy in part . . . For now we see in a mirror dimly" (1 Cor. 13:9, 12). In these biblical confessions, Paul refuses to collapse faith into philosophical or scientific categories that carefully and transparently determine and confirm our comprehension of God, of ourselves, and of the salvific meaning of existence. Faith, on the contrary, inevitably includes a sense of blindness. It never abides in the sanctuary of sight or insight, never reaches the stasis of a secure foundation of clear and distinct rational ideas, but constantly walks in the shadows of uncertainty, gazing into the mirror of a nebulous unknowing.

Likewise, Derrida promotes an essential difference between "pure faith" and any affirmation of determinable knowledge. He asserts that pure faith, s'il y en a, occurs "whenever one gives up not only any certainty but also any determined hope." He insists that pure faith, which comes in association with hope as a certain openness to unexpected events that will have been in some unanticipated future, resists the confining conceptualizations of language and consistently remains apophatic and ineffable, never allowing for the principle of sufficient reason to attenuate the risk and uncertainty of believing.

Interestingly, in associating faith and hope, Derrida betrays a continued "Pauline" perspective on the relationship between faith and reason. The Apostle Paul also applies the tension between faith and sight to the passion of hope: "For in hope we have been saved, but hope that is seen is not hope; for who hopes for what he already sees? But if we hope for what we do not see, with perseverance we wait eagerly for it" (Rom. 8:24-25).

Derrida would gloss this passage with the idea of undecidability, his name for our inability to project, to anticipate, or to determine exactly what will come in the future. If we can program the future, know rationally what lies ahead, then we no longer have pure faith and we no longer move into that future with a pure messianic hope, which indicates that we no longer have to risk our lives or struggle with the fear and trembling of unbelief.

John Caputo would voice a hearty "amen" to Paul's and Derrida's homilies on faith and hope. He regards both of them as "inspired" prophets bringing a word of redemption that proclaims the genuine nature of religion as the poetics of passion and not as the prose of calculated proofs. He looks into Paul's dim mirror and embraces Derrida's messianic undecidability by positing a theology of the "perhaps," an understanding of faith and hope as not so much "being" as "may-being." Maybe there is some object to our faith; maybe there is some reality to our hope. To be sure, a theology of "perhaps" intends to privilege faith (foi) over belief (croyance) in order to ensure the "pure faith" (s'il y en a) that remains open to the unconditional but indeterminable event of an insistent summons to respond faithfully to the in-coming of the impossible, which can, indeed, be expressed using the name of "God."