Editors' Note: This article is part of the Patheos Public Square on Has Hollywood Become Our National Conscience? Read other perspectives here.

We live by stories; the major religions know this. Consider the centrality of the Passover, Jesus' crucifixion, or Buddha's enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree. The best atheist writers know this, with their popular deconversion autobiographies, wonder-filled science tales, and histories of great freethinkers.

For that matter, we all mold our selves around our own idiosyncratic life narratives. Sometimes these can be self-aggrandizing (Donald Trump, anyone?), self-defeating (countless depressed people), or at their best, constructive guides and measures.

Finely crafted movies are a distinctively powerful form of storytelling. With their potent combination of literally larger than life images, stirring music, and deft editing, their stories are felt in a way that only the best books can rival.

So, are movies a social force for good or for evil? In a word, yes.

In short order, I can come up with three examples where movies have instilled or reinforced toxic social ideas. Leni Riefenstahl's films artfully shored up the Nazi agenda. The Birth of a Nation, by genius director D.W. Griffith, is abhorrent KKK propaganda. Innumerable Westerns and superhero flicks promote the deadly fallacy of redemptive violence.

Happily, there are just as many instances of cinematic power harnessed for social good. Well-made, virtuous movies are — to use Roger Ebert's delightful turn of phrase — terrific "empathy-generating machines."

As a far lesser film critic, I'm naturally inclined to agree with the much missed, much loved Ebert. But he had data on his side. As Jonathan Gottschall elucidates in his winsome, erudite book The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human, a copious number of studies have shown that books, television, and movies deepen our morality and heighten our sensitivity to the plight of out-groups.

Take the issue of race. Guess Who's Coming to Dinner? broached the topic of interracial romance in the 1960s. Spike Lee's wrenching Katrina documentary When the Levees Broke exposed the devastating effects of our country's institutional racism. 12 Years a Slave and Django Unchained particularized the gross spectacle of slavery.

Or take gender equality. Norma Rae showed the power of one woman's advocacy for all workers' rights. Even a flighty film like 9 to 5 raised the serious topic of sexual harassment.

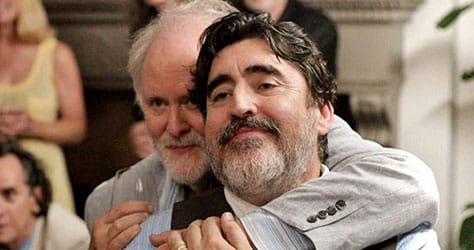

Or how about gay rights? Philadelphia nudged open the door of awareness to same-sex relationships and anti-gay bigotry, just as Brokeback Mountain did a decade later. Love Is Strange and Pride continued these efforts while telling great stories in 2014.

Or how about gay rights? Philadelphia nudged open the door of awareness to same-sex relationships and anti-gay bigotry, just as Brokeback Mountain did a decade later. Love Is Strange and Pride continued these efforts while telling great stories in 2014.

Whether in real life or by way of the big screen, it's much harder to despise an out-group once you get to know its individual members.

Many movies also do the important work of speaking truth to power. Consider one of this year's Oscar front-runners, Spotlight. Even the Vatican has commended this suspenseful, honest retelling of The Boston Globe's efforts to get to the heart of the clerical sexual abuse scandal. Other significant films in recent years — Philomena, Deliver Us from Evil — have underscored how spiritual power corrupts just as surely as political power.

Some of my favorite films are those that expand my circle of empathy, introducing me to causes and concerns about which I would have otherwise remained under-informed. As an insulated college student, The Killing Fields was the first time I learned of the Khmer Rouge's butchery. In This World, a 2002 movie by British director Michael Winterbottom, presciently submerged me in the perils of two young men fleeing a Pakistani refugee camp.