Editors' Note: This article is part of the Patheos Public Square on Moving Past Hatred. Read other perspectives here.

I very much like what psychologist Harriet Lerner says about anger. "Anger," she writes in The Dance of Anger, "is neither legitimate nor illegitimate, meaningful nor pointless. Anger simply is. To ask, 'Is my anger legitimate?' is similar to asking, 'Do I have the right to be thirsty? After all, I just had a glass of water fifteen minutes ago.'"

While this does not strictly contradict the advice from Ephesians 4:26—"In your anger, do not sin"—I've found that many of my fellow white mainline Protestant Christians in the U.S. hear this as saying something like, "In your pool, do not drown." Being risk-averse, we figure we'll just stay out of the pool if those are the stakes. Can't drown if you stay on dry land, thank you very much. Lerner's advice reframes anger into something that people just experience, full stop. Or even better, something we undergo, like thirst. As I go about in the world, processes within and without interact with each other and make me thirsty, or angry. (Or happy, or glum, or bored, or hungry, or in love.)

This squares well with the ancient Hellenistic understanding of the passions, from the Greek pathos or Latin passio: physical things an animal experiences in its dealings with the world. While the Stoics were pretty down on the passions—Cicero called them "vicious"—the later and rather more levelheaded approach of Augustine reserves judgment on the passions as such. True, for Augustine a sinful humanity is likely to turn any strong feeling into something self-defeating, unhelpful, and compulsive. We are apt to turn love of knowledge into smug satisfaction at being smart, affection for another into possessiveness, and so forth. But that's what becomes of the passions in a sinful world. Moreover, in such a world, emotions like longing and sadness can help reorient us away from fleeting pleasures and toward the true source of fulfillment, God. But in any case, there is no staying out of the pool.

Of course, that does not mean we ought to go ahead and plot how much fun it will be to ambush our enemies in the pool and hold their heads underwater. Therein lies the difference between anger and hatred, according to the 13th-century Christian theologian Thomas Aquinas. For Aquinas, the line between anger and hatred is a clear one in theory, though it might be hard for all but the most self-aware person to discern in herself. Do you wish for evil to befall your enemy because that scenario contains an element of good—like, say, you hope that your toxic coworker gets a negative performance review because that would serve him right? Then you're angry. Somewhere in your desire for vengeance is a desire, however unreasonably expressed, for a just world. If, on the other hand, you hope your coworker gets a negative performance review because it would be so delicious to see her suffer? Then you hate her. And that, for Aquinas, is a much bigger deal. Unlike anger, hatred isn't motivated by even a misguided understanding of the good. Therefore, hatred can never be satisfied, never show mercy. Did your coworker mend his ways? Who cares? He doesn't deserve another chance.

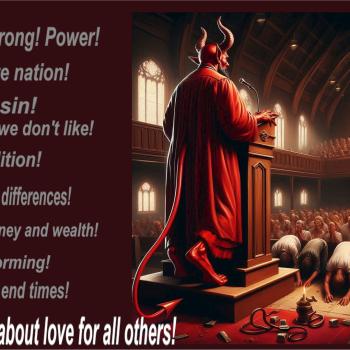

Even if we want to draw the distinction between anger and hatred differently than Aquinas did, it seems to me that there is a lot of value in making the distinction. I referred earlier to the cultural tendency of white mainline U.S. Protestants—my people—to foreclose on anger because it's a negative emotion and we like to be pleasant. This is not particularly helpful, and is decidedly unhelpful in trying to make sense of the justified anger expressed by marginalized groups. Meanwhile, though, the internet often functions like a large fermentation vat into which anger is channeled, contained, and brewed into hatred. Hatred gets clicks. Hatred gets viewers. Many, many people seem to like consuming media jeremiads consisting of precious little analysis, and a great deal of glee at the thought of evil befalling one's enemies.

(I have written some pieces like that in the past. Many people liked them. I now regret them.)

It is not at all my place to tell other faith communities what they should do about hatred. It might be my place, though, to ask this of myself and people somewhat like me: Can we please be angrier at church? I don't mean just politely-disapproving, I-disagree-with-this-bill angry. I mean really, personally angry, in all its magnitudes and dimensions. Annoyed. In a bad mood. Peevish. Irate. Grumpy. Disagreeable. Frustrated. Taking umbrage. Having woken up on the wrong side of the bed. Outraged. Fixin' to spit turpentine on a brushfire.

Can we come to church angry, and then talk? Can we be communities that coach each other on noticing and experiencing our anger, but not letting it turn into hate? Can we maybe then leave, sometimes, still angry—but not hating—and call it a provisional success?

10/13/2015 4:00:00 AM